Where Conductors Fear to Tread (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stockhausen's Cosmic Pulses

Robin Maconie: Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses 2009–14 (copyright) 1 Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses ROBIN MACONIE Some people chase tornados; others go after black holes. From the late 1950s Stockhausen was fascinated by the idea of sounds in rotation and how to realise them in a technical sense, by means of an array of loudspeakers. Completed in 2007, Cosmic Pulses is Stockhausen’s final electronic composition.1 For a number of reasons I believe the composer knew it would be his last. The work was completed in a rush. In many ways, notably in terms of the sound material, which is very basic, it remains a sketch. The music can be described as a massive rotating sound mass, composed in 24 separately spinning frequency layers. The work thickens gradually to 24 layers, then reduces symmetrically upward in an ascending spiral that ends quite abruptly. An audience may experience the sensation of falling headlong into a black hole, or, if one is an optimist, of being carried aloft on the whirlwind like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. A tornado is an effect of a natural imbalance between temperature layers in the atmosphere, tipped into motion by the earth’s rotation, which moves progressively faster toward the equator. The rotating air mass that results spirals upwards and generates a powerful electrical charge. A black hole by comparison is an effect of gravitation creating an imbalance in spacetime. The rotational process that results spirals downward or inward and leads to the extinction of reality as we know it, or again, if one is an optimist, creates a wormhole leading either into another universe, or into our own universe at Robin Maconie: Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses 2009–14 (copyright) 2 another point in time. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

Developing Sound Spatialization Tools for Musical Applications with Emphasis on Sweet Spot and Off-Center Perception

Sweet [re]production: Developing sound spatialization tools for musical applications with emphasis on sweet spot and off-center perception Nils Peters Music Technology Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, QC, Canada October 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. c 2010 Nils Peters 2010/10/26 i Abstract This dissertation investigates spatial sound production and reproduction technology as a mediator between music creator and listener. Listening experiments investigate the per- ception of spatialized music as a function of the listening position in surround-sound loud- speaker setups. Over the last 50 years, many spatial sound rendering applications have been developed and proposed to artists. Unfortunately, the literature suggests that artists hardly exploit the possibilities offered by novel spatial sound technologies. Another typical drawback of many sound rendering techniques in the context of larger audiences is that most listeners perceive a degraded sound image: spatial sound reproduction is best at a particular listening position, also known as the sweet spot. Structured in three parts, this dissertation systematically investigates both problems with the objective of making spatial audio technology more applicable for artistic purposes and proposing technical solutions for spatial sound reproductions for larger audiences. The first part investigates the relationship between composers and spatial audio tech- nology through a survey on the compositional use of spatialization, seeking to understand how composers use spatialization, what spatial aspects are essential and what functionali- ties spatial audio systems should strive to include. The second part describes the development process of spatializaton tools for musical applications and presents a technical concept. -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life. -

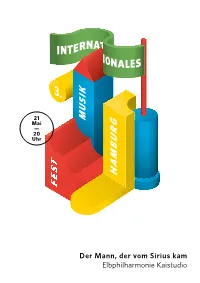

Der Mann, Der Vom Sirius Kam Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio

21 Mai — 20 Uhr Der Mann, der vom Sirius kam Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 20 Uhr Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 21 — Mai BMW 7er DER ANSPRUCH VON MORGEN DER MANN, DER VOM SIRIUS KAM Thomas von Steinaecker Autor David von Bassewitz Zeichner Paul Hübner Musikalische Konzeption, Klangregie Präsentation der neuen Graphic Novel »Der Mann, der vom Sirius kam« von Thomas von Steinaecker und David von Bassewitz. Musik: Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) Karlheinz Stockhausen Tierkreis (Auszüge) (1975) BMW IST LANGJÄHRIGER PARTNER DER ELBPHILHARMONIE Abbildung zeigt Sonderausstattungen. 8331_BMW_Luxury_7er_Elbphilharmonie_Abendprogramm_148x210.indd 1 06.04.2018 08:48:43 MUSIK ALS UTOPIE Wie Karlheinz Stockhausen den Klang der Zukunft schuf. Von Thomas von Steinaecker Darmstadt, Sommer 1951. Bei den »Internationalen Ferienkursen für Neue Musik« herrscht Aufbruchsstimmung. Tagsüber besuchen die jungen Komponisten aus aller Welt Seminare mit Titeln wie »La musique concrète« oder eine Einführung in die Zwölftonmusik, die Theodor W. Adorno anstelle des erkrankten Arnold Schönberg hält. Abends diskutiert man auf den idyllischen Wiesen der Marien- höhe mit Blick über die Stadt, die noch in Trümmern liegt. Mich hat die Vorstel- lung immer berührt, wie hier eine Generation junger Komponisten buchstäblich im Schatten der Apokalypse, die zu diesem Zeitpunkt nur sechs Jahre zurück und ein paar hundert Meter Luftlinie entfernt liegt, mit einem Eifer an der Neuerfindung der eigenen Mittel und Methoden arbeitet, der in der Musikgeschichte einzigartig ist. Ausgerechnet in den heute oft als hoffnungslos verstaubt geltenden und angeblich von »Adenauer-Mief« eingehüllten 1950er Jahre legten die Künstler eine Experimentierfreudigkeit an den Tag, die uns heute zuweilen ziemlich alt aussehen lässt. Interessanterweise gab sich die Musik von allen Künsten am explizitesten utopisch. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Hubert Howe\My Documents\Courses

Musical works of Karlheinz Stockhausen (b. 1928) [Information taken from www.stockhausen.org.] Nr. Chöre für Doris for choir a capella, 1950 Drei Lieder for chorus and chamber orchestra, 1950 Chorale for four-part choir a capella, 1950 Sonatine for violin and piano, 1951 Kreuzspiel (“Cross-play”) for oboe, bass clarinet, piano, percussion, 1951 Formel (“Formula”) for orchestra, 1951 Etüde, musique concrète, 1952 Spiel (“Play”) for orchestra, 1952 Schlagtrio (percussion trio), for piano and 3x2 timpani, 1952 Punkte (“Points”) for orchestra, 1952 (revised, 1962) 1 Kontra-Punkte (“Counter-points”) for 10 instruments, 1952-3 2 Klavierstücke I-IV (Piano pieces I-IV), 1952-3 (Klavierstück IV revised 1961) 3/I Studie I, electronic music, 1954 3/II Studie II, electronic music, 1954 4 Klavierstücke V-X, (Piano pieces V-X), 1954-5 (Klavierstück X revised 1961) 5 Zeitmasze (“Tempi”) for woodwind quintet, 1955-6 6 Gruppen (“Groups”) for three orchestras, 1955-57 7 Klavierstück XI (Piano piece XI), 1956 8 Gesang der Jünglinge (“Song of the Youths”), electronic music, 1955-6 9 Zyklus (“Cycle”) for one percussionist, 1959 10 Carré for four orchestras and choruses, 1959-60 11 Refrain for three players, 1959 12 Kontakte (“Contacts”) for electronic sounds, 1959-60 Kontakte for electronic sounds, piano and percussion, 1959-60 Originale (“Originals”), musical theater with Kontakte, 1961 13 Momente (“Moments”) for soprano, four choral groups and 13 instruments, 1962-4 (Revised 1965, 1998) 14 Plus/Minus 2 x 7 pages for elaboration, 1963 15 Mikrophonie I (“Microphony -

Deutsch Stockhausen Werverz

KURZBIOGRAPHIE Karlheinz Stockhausen 1928 Geboren am Mittwoch, den 22. August in Mödrath bei Köln. 1947 – 51 Studium in Köln an der Staatlichen Hochschule für Musik (Klavier, Schulmusik) und Universität (Germanistik, Philosophie, Musikwissenschaft). Seit 1950 Erste Kompositionen und Aufführungen eigener Werke. (In folgender Aufzählung werden nur einige der 376 Werke und Uraufführungen genannt.) 1951 Serielle Musik: KREUZSPIEL, FORMEL usw. Vermählung mit Doris Andreae; aus der Ehe gingen 4 Kinder hervor: Suja (1953), Christel (1956), Markus (1957), Majella (1961). 1952 Punktuelle Musik: SPIEL, KLAVIERSTÜCKE, SCHLAGTRIO, PUNKTE, KONTRA-PUNKTE usw. Kurse für Rhythmik und Ästhetik bei Olivier Messiaen in Paris; Experimente in der Gruppe ‘musique concrète’ des französischen Rundfunks, Paris, und Realisation einer ETUDE (Konkrete Musik). Erste Synthese von Klangspektren mit elektronischen Sinus-Tönen. Seit 1953 ständiger Mitarbeiter im Studio für Elektronische Musik des WDR Köln (1963 – 1977 künstlerischer Leiter, bis 1990 künstlerischer Berater); Dozent der jährlichen Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt von 1953 bis 1974 und 1996. Erste Kompositionen Elektronischer Musik: Elektronische STUDIEN I und II, GESANG DER JÜNG- LINGE (Beginn der Raum-Musik und der Aleatorischen Musik). 1954 – 56 Parallel zur Forschung und Komposition im WDR Studio für Elektronische Musik Studium der Phonetik und Kommunikationsforschung bei Werner Meyer-Eppler an der Universität Bonn. 1954 – 59 Mitherausgeber der Schriften über serielle Musik » die Reihe«, Universal Edition (Wien). 1956 Uraufführungen von ZEITMASZE in Paris und GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE in Köln. 1957 Uraufführung KLAVIERSTÜCK XI (Variable Musik) in New York. 1958 Experimente neuer elektronischer Klangsynthesen und Raumprojektionen für KONTAKTE. 32 ‘concert-lectures’ an amerikanischen Universitäten; seitdem re gelmäßig längere Tourneen als Dirigent und Interpret eigener Werke (seit 1959 mit kleineren Solisten-Gruppen). -

Course Brochure 2022 English

Nine Concerts: July 9 th to 17 th 2022 Wednesday, July 13 th , 8 p.m., Sülztalhalle Courses Stock hau sen Concerts Faculty and works which will be taught in master Sound projection (Instructors: Kathinka Pasveer, sound th Saturday, July 9 , 5 p.m. KLANG 4th Hour: HEAVEN’S DOOR classes projectionist; Reinhard Klose, sound engineer) for a percussionist and a child In the context of the daily rehearsals and concerts with and Courses Kürten 202 2 opening Suzanne Stephens (clarinet, basset-horn, bass clarinet) Festive of the courses at the and Stockhausen’s closest technical collaborators, anyone who and Kathinka Pasveer (flute, alto flute, piccolo) Karlheinz-Stockhausen-Platz . MICHAEL’S CALL st is interested in learning more about the sound projection from July 9 th to 17 th 1 participants’ concert will be teach ing all Stock hau sen works com posed for their in performances of Stockhausens electronic, vocal and for 4 trumpets will open and close the ceremony respec tive instru ments. Thursday, July 14 th , 8 p.m., Sülztalhalle instrumental works can experience, first-hand, which “Sometimes music vibrates beyond the clouds, and we can Marco Blaauw (trumpet, piccolo trumpet, flugelhorn): aspects must be addressed and how they are can be solved no longer hear its echo. Very rarely is it truly infinite; then ARIES, TIERKREIS, IN FREUNDSCHAFT, DONNERSTAGS- from the sound engineering point of view. it makes us forget the Earth. The great masters sense that Saturday, July 9 th , 8 p.m. , Sülztalhalle HALT (of THURSDAY from LIGHT) GRUSS, MICHAELS-RUF, MICHAELs REISE UM DIE ERDE, HALT, In addition to the daily concerts, open rehearsals, master they have one last thing to say, and that life is coming to an for trumpet and double bass MISSION und HIMMELFAHRT, VISION, OBERLIPPENTANZ, SIRIUS (Summer Version ) PIETÀ, TRUMPETENT, MICHAELION, BASSETSU-TRIO, QUITT, classes, and concert introductions, there will be seminars, end –. -

SIRIUS 3RK1105-1.E04-.CA0 AS-Interface IEC 61508/EN 954-1 Sicherheitsmonitor Us SAFETY at WORK

SIRIUS 3RK1105-1.E04-.CA0 AS-Interface IEC 61508/EN 954-1 Sicherheitsmonitor us SAFETY AT WORK Betriebsanleitung Bestell-Nr.: 3RK1701-2MB21-0AA0 Deutsch Vor der Installation, dem Betrieb oder der Wartung des Geräts muss diese Anleitung gelesen und verstanden werden. Maßzeichnung 45 115 ! GEFAHR 94 65 7,2 Gefährliche Spannung. Lebensgefahr oder Gefahr schwerer Verletzung. Vor Beginn der Arbeiten Anlage und Gerät spannungsfrei schalten. 5 102 Eine sichere Gerätefunktion ist nur mit zertifizierten Komponenten 91,5 68,2 105,9 82,6 gewährleistet! 37x118 37x139 Unter Berücksichtigung der Umgebungsbedingungen müssen die Geräte in Schaltschränke der Schutzart IP32, IP43 oder IP54 eingebaut werden. Wichtiger Hinweis Die hier beschriebenen Produkte wurden entwickelt, um als Teil einer Gesamt- anlage oder Maschine sicherheitsgerichtete Funktionen zu übernehmen. Ein komplettes sicherheitsgerichtetes System enthält in der Regel Sensoren, Aus- 28,8 werteeinheiten, Meldegeräte und Konzepte für sichere Abschaltungen. Es liegt im Verantwortungsbereich des Herstellers einer Anlage oder Maschine die kor- 6 rekte Gesamtfunktion sicherzustellen. Die Siemens AG, ihre Niederlassungen und Beteiligungsgesellschaften (im Folgenden “Siemens”) sind nicht in der Lage, Achtung alle Eigenschaften einer Gesamtanlage oder Maschine, die nicht durch Siemens Die vollständige Beschreibung zur Konfigurationssoftware und die konzipiert wurde, zu garantieren. technische Beschreibung zum Sicherheitsmonitor ist unbedingt zu Siemens übernimmt auch keine Haftung für Empfehlungen, -

Stockhausen STIMMUNG & COSMIC PULSES

Stockhausen STIMMUNG & COSMIC PULSES Monday 20 November 2017 7.30pm, Hall Stockhausen STIMMUNG interval 30 minutes Stockhausen COSMIC PULSES Singcircle Gregory Rose bass/director Jacqueline Barron soprano Zoë Freedman soprano Heather Cairncross mezzo-soprano Guy Elliott tenor Angus Smith tenor Rolando Paolo Guerzoni Paolo Rolando Robert Henke laser artist Kathinka Pasveer sound projection Stephen Montague assistant sound projection Reinhard Klose sound engineer Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel. 020 3603 7930) Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Karlheinz Stockhausen was a towering figure the 10th anniversary of Stockhausen’s in the history of 20th- and 21st-century music, death (which falls next month), but also one who literally changed the sound of the 40th anniversary of Singcircle’s first music and the way we listen to it. Tonight’s performance of the work in the Round concert presents two seminal works from House. It is also the last-ever performance opposite ends of his career. It is intended of STIMMUNG by Singcircle. -

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN Dienstag Aus Licht 24 Octobre 2020 Dienstag Aus Licht Composition, Livret, Action Scénique Et Gestes, Karlheinz Stockhausen

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN Dienstag aus Licht 24 octobre 2020 Dienstag aus Licht Composition, livret, action scénique et gestes, Karlheinz Stockhausen Le Balcon, la Philharmonie de Paris et le Festival d’Automne à Paris s’associent pour produire la totalité Composition : 1977 pour la première version de Jahreslauf ; 1988-1991 pour l’opéra complet du cycle Licht de Karlheinz Stockhausen. Commandes : Gruss : Université de Cologne (1988) ; Jahreslauf : National Theater de Tokyo (1977) ; Invasion : Festival d’Automne à Paris / Michel Guy (1989) pour l’Ensemble intercontemporain ; Invasion avec Pietà : Alte Oper Frankfurt pour les Frankfurt Feste (1991) ; Première version Depuis sa création en 1972, le Festival d’Automne à Paris a produit et présenté nombre d’œuvres de Karlheinz concertante (mai 1992) : Fondation Gulbenkian, Lisbonne ; reprise en juin 1992 au Muziektheater/Holland Festival Stockhausen, dont l’opéra Montag aus Licht en 1988. Dès 1995, le Festival et la Philharmonie de Paris se sont Création scénique intégrale : le 28 mai 1993 à l’Opéra de Leipzig – Mise en scène, Johannes Conen, Uwe Wand, sous la direction du compositeur réunis pour explorer ensemble l’œuvre du compositeur visionnaire : Momente en 1998, des œuvres du cycle E ectif : voir Synopsis page 4 Éditeur : Stockhausen Verlag Klang en 2008, Trans en 2013 et enfi nInori en 2018, dans la Grande salle Pierre Boulez. Durée : 2h40 plus 45 minutes d’entracte Depuis 2018, Le Balcon et Maxime Pascal s’emparent avec sensibilité et talent de ces partitions pour pro- duire, en sept ans, jusqu’en 2024, chacune des sept Journées du cycle Licht. Après Donnerstag aus Licht (2018, Opéra Comique) et Samstag aus Licht (2019, Philharmonie de Paris), Dienstag aus Licht est la troi- Direction artistique, Maxime Pascal, Nieto, Damien Bigourdan sième Journée présentée. -

To Download Program Notes

San Francisco Tape Music Festival Program Notes for Sunday, January 28, 2007 Visit http://sfSound.org/tape for links to more information about the composers and their work. Karlheinz Stockhausen :: HYMNEN :: Regions I and II [ 57:52 ] :: Regions III and IV [ 56:07 ] Short-wave. The aural window on the world. Babble and squeak. " .... get across the ocean in a few seconds". Cut the ether with the tuning dial and hit the edge of a station somewhere far, far away. A single speaking voice emerges. Or maybe it's a large choir voicing a robust melody. Perhaps it's the insatiable bleeping of a Morse code transmission, the actual message submerged in secret rhythms. At the edge the sound fizzes and swirls, then fades and tumbles back. Turn the dial. Slowly, precisely, deliberately. Searching for the don't-know-what. Hiss and crackle rub against high pitched drones that recall the burnished shriek of a jet engine. A voice reads a string of numbers, slowly and deliberately. Keep turning. Suddenly drums and trumpets and unison voices sing heartily, passionately, joyously - an anthem, a national anthem. It shifts and twists and begins to throb like a distant pulsar. Keep turning. Stations run together transforming noise, via melody, into speech then headlong into electro-gabble before swirling back again into noise. This is the world of HYMNEN: short-wave scramble, voices, distant places and music. Recordings of familiar tunes, national anthems (in German: 'Hymnen'), are transformed as if filtered through a billion stars. Stockhausen writes, "Anthems, the national anthems, are the most popular music there is.