Into Silence: Feminism Under the Third Reich By: Erin Kruml

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulnara Shahinian and Democracy Today Armenia Are Awarded the Anita Augspurg Prize "Women Rebels Against War"

Heidi Meinzolt Laudatory speech, September 21 in Verden: Gulnara Shahinian and Democracy today Armenia are awarded the Anita Augspurg Prize "Women rebels against war". Ladies and gentlemen, dear friends, dear Gulnara, We are celebrating for the second time the Anita Augspurg Award "Women rebels against war". Today, exactly 161 years ago, the women's rights activist Anita Augspurg was born here in Verden. Her memory is cherished by many dedicated people here, in Munich, where she lived and worked for many years, and internationally as co-founder of our organization of the "International Women's League for Peace and Freedom" more than 100 years ago With this award we want to honour and encourage women who are committed to combating militarism and war and strive for women’s rights and Peace. On behalf of the International Women's League for Peace and Freedom, I want to thank all those who made this award ceremony possible. My special thanks go to: Mayor Lutz Brockmann, Annika Meinecke, the city representative for equal opportunities members of the City Council of Verden, all employees of the Town Hall, all supporters, especially the donors our international guests from Ukraine, Kirgistan, Italy, Sweden, Georgia who are with us today because we have an international meeting of the Civic Solidarity Platform of OSCE this weekend in Hamburg and last but not least Irmgard Hofer , German president of WILPF in the name of all present WILPFers Before I talk more about our award-winner, I would like to begin by reminding you the life and legacy of Anita Augspurg, with a special focus on 1918, exactly 100 years ago. -

Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Female Nazi Perpetrators

Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 19 Article 13 2015 Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Female Nazi Perpetrators Follow this and additional works at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Recommended Citation Mercure, Kara (2015) "Female Nazi Perpetrators," Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 19 , Article 13. Available at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal/vol19/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity at OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Female Nazi Perpetrators Kara Mercure Nazi women perpetrators have evolved in literary works as they have become more known to scholars in the last 15 years. However, public knowledge of women’s involvement in the regime is seemingly unfamiliar. Curiosity in the topic of women’s motivation as perpetrators of genocide and war crimes has developed in contrast to a stereotypical perception of women’s gender roles to be more domesticated. Much literature has been devoted to explaining Nazi ideology and how women fit into the system. Claudia Koonz’s, Mother’s in the Fatherland, demonstrates the involvement of women in support of National Socialism. The book focuses on women in support of the regime and how they supported the regime through domestic means. Robert G. Moeller’s, The Nazi State and German Society, also examines how women were drawn to National Socialism and how their ideals progressed through the regime. -

Gender and Colonial Politics After the Versailles Treaty

Wildenthal, L. (2010). Gender and Colonial Politics after the Versailles Treaty. In Kathleen Canning, Kerstin Barndt, and Kristin McGuire (Eds.), Weimar Publics/ Weimar Subjects. Rethinking the Political Culture of Germany in the 1920s (pp. 339-359). New York: Berghahn. Gender and Colonial Politics after the Versailles Treaty Lora Wildenthal In November 1918, the revolutionary government of republican Germany proclaimed the political enfranchisement of women. In June 1919, Article 119 of the Versailles Treaty announced the disenfranchisement of German men and women as colonizers. These were tremendous changes for German women and for the colonialist movement. Yet colonialist women's activism changed surprisingly little, and the Weimar Republic proved to be a time of vitality for the colonialist movement. The specific manner in which German decolonization took place profoundly shaped interwar colonialist activism. It took place at the hands of other colonial powers and at the end of the first "total" war. The fact that other imperial metropoles forced Germany to relinquish its colonies, and not colonial subjects (many of whom had tried and failed to drive Germans from their lands in previous years), meant that German colonialists focused their criticisms on those powers. When German colonialists demanded that the Versailles Treaty be revised so that they could once again rule over Africans and others, they were expressing not only a racist claim to rule over supposed inferiors but also a reproach to the Entente powers for betraying fellow white colonizers. The specific German experience of decolonization affected how Germans viewed their former colonial subjects. In other cases of decolonization, bitter wars of national liberation dismantled fantasies of affection between colonizer and colonized. -

Split Infinities: German Feminisms and the Generational Project Birgit

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Oxford German Studies on 15 April 2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00787191.2015.1128648 Split Infinities: German Feminisms and the Generational Project Birgit Mikus, University of Oxford Emily Spiers, St Andrews University When, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the German women’s movement took off, female activists/writers expressed a desire for their political work to initiate a generational project. The achievement of equal democratic rights for men and women was perceived to be a process in which the ‘democratic spirit’ was instilled in future generations through education and the provision of exceptional role models. The First Wave of the women’s movement laid the ground, through their writing, campaigning, and petitioning, for the eventual success of obtaining women’s suffrage and sending female, elected representatives to the Reichstag in 1919. My part of this article, drawing on the essays by Hedwig Dohm (1831–1919) analyses how the idea of women’s political and social emancipation is phrased in the rhetoric of a generational project which will, in the short term, bring only minor changes to the status quo but which will enable future generations to build on the foundations of the (heterogeneous, but mostly bourgeoisie-based) first organised German women’s movement, and which was intended to function as a generational repository of women’s intellectual history. When, in the mid-2000s, a number of pop-feminist essayistic volumes appeared in Germany, their authors expressed the desire to reinvigorate feminism for a new generation of young women. -

Hard Hearts; the Volksgemeinschaft As an Indicator of Identity Shift Kaitlin Hampshire James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2017 Hard times; Hard duties; Hard hearts; The Volksgemeinschaft as an indicator of identity shift Kaitlin Hampshire James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Other German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hampshire, Kaitlin, "Hard times; Hard duties; Hard hearts; The oV lksgemeinschaft as na indicator of identity shift" (2017). Masters Theses. 488. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/488 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hard Times; Hard Duties; Hard Hearts; The Volksgemeinschaft as an Indicator of Identity Shift Kaitlin Hampshire A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Christian Davis Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Michael Gubser Dr. Gabrielle Lanier To Mom and Dad, I do not know how I could have done this without you! II Acknowledgements Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my director Dr. Christian Davis for his support of my Master’s Thesis. Besides my director, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Michael Gubser and Dr. Gabrielle Lanier. My deepest thanks goes to my Graduate Director and Mentor Dr. -

Women's Denunciations in the Third Reich

Vandana Joshi. Gender and Power in the Third Reich: Female Denouncers and the Gestapo (1933-45). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. xx + 229 pp. $65.00, cloth, ISBN 978-1-4039-1170-4. Reviewed by Julia Torrie Published on H-German (September, 2004) In June 1939, Frau Hof, a working-class wom‐ Vandana Joshi's Gender and Power in the an from Düsseldorf, made a visit to the Gestapo. Third Reich: Female Denouncers and the Gestapo She had recently discovered that her husband had (1933-45) brings to light many cases like this one. lived with a prostitute before marrying her and It is a study of denunciations in the Third Reich that he carried a venereal disease. When Frau Hof that, Joshi argues, enabled women to "tilt the refused to sleep with her husband because of his scales of power in their favour, to appropriate illness, he became violent. Moreover, Frau Hof power and influence, to fght for their dignity and told the Gestapo, "He is left oriented, I can not to subvert the patriarchal code of domination and take it any longer.... He says that he would never subordination" (p. 47). Members of the apparently become a National Socialist." The Gestapo looked "weaker" sex used denunciations as a way to at‐ into the case, noting that there was significant dis‐ tack the strong, "playing the game of use and cord between the couple, and that Frau Hof had abuse of power in an uninhibited and fearless already asked for her husband to be banned from way" (p. -

Love Between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials Isabel Meusen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meusen, I.(2015). Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3082 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials by Isabel Meusen Bachelor of Arts Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2007 Master of Arts Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2011 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Agnes Mueller, Major Professor Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Federica Clementi, Committee Member Laura Woliver, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Isabel Meusen, 2015 All Rights reserved. ii Dedication Without Megan M. Howard this dissertation wouldn’t have made it out of the petri dish. Words will never be enough to express how I feel. -

Resolutions Adopted

INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF WOMEN THE HAGUE - APRIL 28TH TO MAY 1ST 1915 RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED '. International Congress of Women THE HAOUE = THE NETHERLANDS. APRIL 28th TO MAY 1st. 1915. PRESIDENT OF THE CONGRESS: JANE ADDAMS. International Committee of the Congress: LEOP. KULKA, ~ Austria. OLGA MISAR, EUGENIE HAMER, ~ B I. MARGUERITE SARTEN, ~ e glUm. THORA DAUGAARD, ~ D k enmar • CLARA TYBJERG, Dr. ANITA AUGSPURG, ~ Germany. LIDA GUSTAVA HEYMANN, Secretary& Interpreter, CHRYSTAL MACMILLAN, Secretary, ~ Great Britain and Ireland. KATHLEEN COURTNEY, Interpreter, ~ VILMA GLUCKLICH, ~ Hungary. ROSIKA SCHWIMMER, ~ ROSE GENONI, Italy. Dr. ALETTA JACOBS, l' HANNA VAN BIEMA-HYMANS, Secretary, Netherlands. Dr MIA BOISSEVAIN, Dr. EMILY ARNESEN, l N LOUISA KEILHAU, l orway. ANNA KLEMAN, ~ S d we en. EMMA HANSSON, JANE ADDAMS, President, U.S.A. FANNIE FERN ANDREWS, SOME PARTICULARS ABOUT THE CONGRESS. How the Congress was called. The scheme of an International Congress of Women was formulated at a small conference of Women from neutral and belligerent countries, held at Amsterdam, early in Febr. 1915. A preliminary programme was drafted at this meeting, and it was agreed to request the Dutch Women to form a Com mittee to take in hand all the arrangement for the Congress and to issue the invitations. Finance. The expenses of the Congress were guaranteed by British, Dutch and German Women present who all agreed to raise one third of the sum required. Membership. Invitations to take part in the Congress were sent to women's organisations and mixed organisations as well as to individual women all over the world. Each organisation was invited to appoint two delegates. -

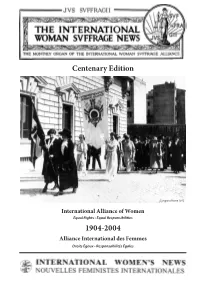

IAW Centenary Edition 1904-2004

Centenary Edition Congress Rome 1923 International Alliance of Women Equal Rights - Equal Responsibilities 1904-2004 Alliance International des Femmes Droits Égaux - Responsabilités Égales Centenary Edition: Our Name 1904-1926 First Constitution adopted in Berlin, Germany, June 2 & 4, 1904 Article 1 - Name: The Name of this organization shall be the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) Alliance Internationale pour le suffrage des Femmes Weltbund für Frauen-stimmrecht 1926-1949 Constitution adopted in Paris, 1926 Article 1 - Name: The name of the federation shall be the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship (IAWSEC) Alliance Internationale pour le suffrage des Femmes et pour l’Action civique et politique des Femmes 1949-2004 The third Constitution adopted in Amsterdam, 1949 Article 1 - Name: The name of the federation shall be the International Alliance of Women, Equal Rights - Equal Responsibilities (IAW) L’Alliance Internationale des Femmes, Droits Egaux - Responsabilités Égales (AIF) Centenary Edition:Author Foreword Foreword My personal introduction to the International Alliance somehow lost track of my copy of that precious document. of Women happened in dramatic circumstances. Having Language and other difficulties were overcome as we been active in the women’s movement, I was one of those scrounged typewriters, typing and carbon paper, and were fortunate to be included in the Australian non-government able to distribute to all of the United Nations delegations delegation to Mexico City in 1975. our -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy..................................................................................... -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future. -

Canadian Woman Studies Feminist Journalism Ies Cahiers De La Femme

Feminist Collections A Quarterly of Women's Studies Resources Volume 18, No.4, Summer 1997 CONTENTS From the Editors Book Reviews The Hearts and Voices of Midwestern Prairie Women by Barbara Handy-Marchello Not Just White and Protestant: Midwestern Jewish Women by Susan Sessions Rugh Beyond Bars and Beds: Thriving Midwestern Queer Culture by Meg Kavanaugh Multiple Voices: Rewriting the West by Mary Neth The Many Meanings of Difference by Mary Murphy Riding Roughshod or Forging New Trails? Two Recent Works in Western U.S. Women's History by Katherine Benton Feminist Visions Flipping the Coin of Conquest: Ecofeminism and Paradigm Shifts by Deb Hoskins Feminist Publishing World Wide Web Review: Eating Disorders on the Web by Lucy Serpell Computer Talk Compiled by Linda Shult New Reference Works in Women's Studies Reviewed by Phyllis Holman Weisbard and others Periodical Notes Compiled by Linda Shult Items of Note Compiled by Amy Naughton Books Recently Received Supplement: Index to Volume 18 FROMTHE EDITORS: About the time we were noticing a lot of new book titles corning out about the history of women in the U.S. West and Midwest, a local planning committee for University of Wisconsin-Extension was starting to pull together a conference focusing on Midwest women's history. That conference took place in early June and included some really exciting research. There were sessions on the interactionslcultural exchange between missionary women and Dakota women in the Minnesota area; Illinois women in the legal profession around 1869; violations of class, race, and gender expectations by prostitutes in Mis- souri, Catholic Sisters teaching in public schools in 19th-century Wisconsin; Midwestern women's clubs; Hmong women's history and culture in the Mid- west; Twin Cities working women in the early 20th century; the world of Harriet and Dred Scott; and so much more territory was covered in this two-day get- together.