Resiliency in Tourism Transportation Case Studies of Japanese Railway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Urban Public Transport Systems and Cycling Summary And

CPB Corporate Partnership Board Integrating Urban Public Transport Systems and Cycling 166 Roundtable Summary and Conclusions Integrating Urban Public Transport Systems and Cycling Summary and Conclusions of the ITF Roundtable on Integrated and Sustainable Urban Transport 24-25 April 2017, Tokyo Daniel Veryard and Stephen Perkins with contributions from Aimee Aguilar-Jaber and Tatiana Samsonova International Transport Forum, Paris The International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organisation with 59 member countries. It acts as a think tank for transport policy and organises the Annual Summit of transport ministers. ITF is the only global body that covers all transport modes. The ITF is politically autonomous and administratively integrated with the OECD. The ITF works for transport policies that improve peoples’ lives. Our mission is to foster a deeper understanding of the role of transport in economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion and to raise the public profile of transport policy. The ITF organises global dialogue for better transport. We act as a platform for discussion and pre- negotiation of policy issues across all transport modes. We analyse trends, share knowledge and promote exchange among transport decision-makers and civil society. The ITF’s Annual Summit is the world’s largest gathering of transport ministers and the leading global platform for dialogue on transport policy. The Members of the Forum are: Albania, Armenia, Argentina, Australia, Austria, -

N7 Stroll the Coast on Horseback ROUTE N8 Exciting Activities in The

N7 Stroll the coast on horseback ROUTE Chance for a gallant canter over the sand on horseback. This is an activity you rarely can experience elsewhere. Best season ROUTE Kaihin-Makuhari Narita International Tokyo Sta. Sta. Airport JR Limited Express JR Narita Line Wakshio JR Keiyo Line Rapid train For Zushi For Awa-Kamogawa For Kazusa-Ichinomiya Station Chiba Sta. JR Sotobo Line For Awa-Kamogawa Approx. 1hr 1min Approx. 48mins Approx. 2hr 6mins 2,420 yen 970 yen 1,490 yen Kazusa-Ichinomiya Sta. Start/Goal 40mins+ 4,500 yen Approx. 10mins by free shuttle bus from Kazusa-Ichinomiya Station (call from station following arrival on day) N7-1 Ichinomiya Horse Riding Center Approx. 10mins by free shuttle bus from Ichinomiya Horse Riding Center (call from station N7-1 Ichinomiya Horse Riding Center following arrival on day) Enjoy carefree horse riding on the beach. Various courses are available depending on levels of horse riding experience. Kujukuri Beach is right beside Horse Riding Center. There is a beginner’s course to 所 9963 Ichinomiya, Ichinomiya-machi, Chosei-gun 0475-42-2851 enjoy horse riding on the shore. Wear clothing that allows ease-of-movement. 9:00-17:00 (Last admission16:00) 休 Wednesday (may be closed in lieu of holiday) Beginners horse leading (20mins) 4,500 yen N8 Exciting activities in the midst of greenery ROUTE Enjoy new types of attractions in the forest that make you feel united with the nature. Best season ROUTE Tokyo Sta. Kaihin-Makuhari Narita International A new type of amusement Sta. Airport park where you fly around in the forest like Tarzan wearing a customized harness. -

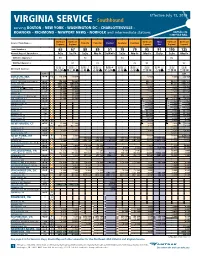

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's

SERVICE DELIVERY TO INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTH ASIA’S MEGA CITIES The Role of State and Non‐State Actors By Faisal Haq Shaheen H.B.Sc. (University of Toronto, 1995), M.B.A. (York University, 1997), M.A. (Ryerson University, 2009) a Dissertation presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the program of Policy Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Faisal Haq Shaheen 2017 i Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's Mega Cities, the Role of State and Non‐State Actors, Ph.D., 2017, Faisal Haq Shaheen, Policy Studies, Ryerson University Abstract This interdisciplinary research project compares service delivery outcomes to informal settlements in South Asia’s largest urban centres: Dhaka, Karachi and Mumbai. These mega cities have been overwhelmed by increasing demands on limited service delivery capacity as growing clusters of informal settlements, home to significant numbers of informal sector workers, struggle to obtain basic services. -

Pdf/Rosen Eng.Pdf Rice fields) Connnecting Otsuki to Mt.Fuji and Kawaguchiko

Iizaka Onsen Yonesaka Line Yonesaka Yamagata Shinkansen TOKYO & AROUND TOKYO Ōu Line Iizakaonsen Local area sightseeing recommendations 1 Awashima Port Sado Gold Mine Iyoboya Salmon Fukushima Ryotsu Port Museum Transportation Welcome to Fukushima Niigata Tochigi Akadomari Port Abukuma Express ❶ ❷ ❸ Murakami Takayu Onsen JAPAN Tarai-bune (tub boat) Experience Fukushima Ogi Port Iwafune Port Mt.Azumakofuji Hanamiyama Sakamachi Tuchiyu Onsen Fukushima City Fruit picking Gran Deco Snow Resort Bandai-Azuma TTOOKKYYOO information Niigata Port Skyline Itoigawa UNESCO Global Geopark Oiran Dochu Courtesan Procession Urabandai Teradomari Port Goshiki-numa Ponds Dake Onsen Marine Dream Nou Yahiko Niigata & Kitakata ramen Kasumigajo & Furumachi Geigi Airport Urabandai Highland Ibaraki Gunma ❹ ❺ Airport Limousine Bus Kitakata Park Naoetsu Port Echigo Line Hakushin Line Bandai Bunsui Yoshida Shibata Aizu-Wakamatsu Inawashiro Yahiko Line Niigata Atami Ban-etsu- Onsen Nishi-Wakamatsu West Line Nagaoka Railway Aizu Nō Naoetsu Saigata Kashiwazaki Tsukioka Lake Itoigawa Sanjo Firework Show Uetsu Line Onsen Inawashiro AARROOUUNNDD Shoun Sanso Garden Tsubamesanjō Blacksmith Niitsu Takada Takada Park Nishikigoi no sato Jōetsu Higashiyama Kamou Terraced Rice Paddies Shinkansen Dojo Ashinomaki-Onsen Takashiba Ouchi-juku Onsen Tōhoku Line Myoko Kogen Hokuhoku Line Shin-etsu Line Nagaoka Higashi- Sanjō Ban-etsu-West Line Deko Residence Tsuruga-jo Jōetsumyōkō Onsen Village Shin-etsu Yunokami-Onsen Railway Echigo TOKImeki Line Hokkaid T Kōriyama Funehiki Hokuriku -

Page 1 of 8 PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Emai

PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Email: [email protected] RESUME Summary Phil Craig has 50 years of experience in the rail transit and railroad field. My expertise is in planning, design, construction, and operation of heavy rail rapid transit systems (metros or subways), light rail transit systems, suburban or regional (commuter) rail systems, high-speed passenger railways, and main line passenger and freight railroads. My broad technical knowledge as a transportation planner and analyst encompasses a wide range of planning, operations, and management areas. I have held significant management positions with transport organizations serving large metropolitan areas in the United States, Great Britain and Greece, as well having been a consultant on rail projects in Canada, India, South Korea, Taiwan and Turkey. Education Bachelor of Science (Cum Laude), Public Utilities and Transportation, New York University, New York, New York, 1963 Professional Data Past Chairman (1973-76) and Committee Member (1972-80), Subcommittee on Federal Rules and Regulations Committee on Mobility for the Elderly and Handicapped American Public Transit Association, Washington, D.C., USA Member, Light Rail Transit Association, London, England Member, Light Rail Panel, New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers Experience Independent Transportation Consultant – March 2009 to July 2009 Project: Honolulu High Capacity Transit Corridor Project, Honolulu, O'ahu, Hawai'i Clients: Kamehameha Schools and Honolulu Chapter of American Institute of Architects Assignment: Analyze Potential for Use of Light Rail Transit Technology Roles: Consultant to Kamehameha Schools and Adviser to AIA Honolulu Prepared a Light Rail Transit Feasibility Report for Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate (the largest private landholder in the Hawaiian Islands). -

SCAJ World Specialty Coffee Conference and Exhibition 2021

The Biggest Specialty Coffee Event in Asia Information for Exhibitors SCAJ World Specialty Coffee Conference and Exhibition 2021 W F E R November 17 D -19 I ,2021 TOKYO BIG SIGHT Aomi Exhibition Hall A https://www.scajconference.jp/en/ Organized by Specialty Coffee Association of Japan SCAJ2021 Event Overview Greeting Katsuhiko Hasegawa Vice-chairman Masahiro Kanno Specialty Coffee Association of Japan Chairman Committee Chair Specialty Coffee Association of Japan Exhibition & Conference Committee Dear all, Dear all, We would like to express our sincere gratitude for your continued support for Greetings for your continued support of SCAJ. Thanks to all of you, SCAJ is Specialty Coffee Association of Japan. now celebrating its 18th anniversary, in commemoration of which we have made a new start as we prepare to hold our 16th exhibition this year. In 2020, due to the worldwide spread of the new coronavirus, our annual SCAJ exhibition was canceled. Coffee consumption at home is growing significantly At the previous exhibition, a total of 201 companies including specialty contrary to the impact on the food and beverage industry in general. New coffee-related companies and organizations from 23 countries including normal has also taken root, and it seems that the number of people brew various coffee producing countries as well as Japan and other areas of the coffee at home and on their own are increasing. It is hard to imagine that the world participated in the event. During the three day event 33,978 people corona wreck will converge in a short period of time, but let's continue our from 47 countries visited the 352 booths which were set up as part of activities in cooperation with each other while taking proper measures. -

JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure Of

Republic of India Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure of Mumbai Metro Line 3 Project in India Final Report October 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan International Consultants for Transportation Co., Ltd. PADECO Co., Ltd. 4R Metro Development Co., Ltd JR 15-046 Table of Contents Chapter 1 General issues for the management of urban railways .............................. 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Management of urban railways ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Construction of urban railways ...................................................................................... 12 1.4 Governing Structure ........................................................................................................ 17 1.5 Business Model ................................................................................................................. 21 Chapter 2 Present situation in metro projects ............................................................ 23 2.1 General .............................................................................................................................. 23 2.2 Metro projects in the world ............................................................................................. 23 2.3 Summary........................................................................................................................ -

ESCAP PPP Case Study #4

Public-Private Partnerships Case Study #4 Land Value Capture Mechanism: The Case of the Hong Kong MTR by Mathieu Verougstraete and Han Zeng (July 2014) This case study presents how a property development programme has been used to finance Hong Kong’s public transport system and discusses whether this model is replicable in other countries. LAND VALUE CAPTURE MECHANISM includes railways, trams, buses, minibuses, taxis and ferries.2 More than 90 per cent of Land value capture mechanisms follow the all motorized trips are by public transport, the 3 basic logic that enhanced accessibility to highest market share in the world. attractive and efficient transport systems adds value to land and real estate. To achieve these impressive results, major investments had to be made in public This value addition has been confirmed by transport systems. A key actor in the sector several researches. For example, research has been the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway indicates that housing price premiums in Corporation (MTRC), established in 1975 to Hong Kong are in the range of 5 to 17 per provide metro services. Its entire system now cent for units in proximity to a railway. This stretches 218.2 km and has 84 stations and premium can even exceed 30 per cent if 68 light rail stops. properties incorporate transit-oriented design, such as structures that facilitate pedestrian The sections below will describe how MTRC access to commercial amenities or provide has managed to mobilize siginificant financial pathways that are connected with stations.1 resources for its network development. As this value premium results from public MTRC BUSINESS MODEL investments, it is reasonable for public authorities to try to capture the surplus. -

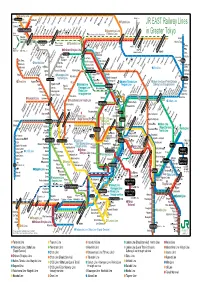

JR Railways Lines in Greater Tokyo

- 31 Joetsu- Line - Nikko- Line Shibukawa 渋川 Maebashi Kiryu Sano 32 - - Agatsuma Line Yagihara - Omata Tomita Ryomo Line oshima KomagataIsesaki Iwajuku Iwafune Tochigi JR EAST Railway Lines Kunisada Ashikaga Maebashi Yamamae Ohirashita Omoigawa Gumma-Soja 新前橋 Shim-Maebashi 17 - Utsunomiya Line Joetsu Kita- ( - ) in Greater Tokyo Shinkansen Ino KuraganoShimmachiJimboharaHonjoOkabeFukayaKagohara GyodaFukiage KonosuKonosuKitamotoOkegawaKita-AgeoAgeo Tohoku.Yamagata.Akita Shinkansen Tohoku Line KoganeiJichiidaiIshibashiSuzumenomiya Takasaki Miyahara tonyamachi Hitachi - akasaki Honjowaseda Joetsu. Nagano Hitachi-Taga 高崎 Kumagaya 18 Takasaki Line Oyama Utsunomiya Ujiie Yaita T 本庄早稲田 熊谷 Shinkansen Line Toro Kuki - Koga Nogi 小山 宇都宮 Nozaki Kuroiso Omika Omiya Shin- OkamotoHoshakuji Kataoka Nagano Higashi- Hasuda Shiraoka Higashi- 3 - Shiraoka Kurihashi Mamada 宝積寺 Tokai Shinkansen Shin-etsu Line Shonan-Shinjuku Line Kamasusaka Saitama- Karasuyama Line Nishi-NasunoNasushiobara那須塩原 Sawa odo Kawagoe Washinomiya Kita-Fujiokaansho Y orii Shintoshin T Y 川越 Omiya Suigun Line Katsuta Kodama Takezawa Nishi- Kita-Yono Yono Matsuhisa Kawagoe 大宮 Oku-Tama Gumma-Fujioka Kita-Urawa Yuki Mito 16 - Orihara Nisshin Yono-Hommachi Otabayashi Yuki Iwase Hachiko Line Ogawamachi Matoba Sashiogi Urawa Niihari Yamato Haguro Inada Shiromaru Minami-Yono Higashi- Tamado Fukuhara 水戸 Kairakuen Myokaku Kasahata Kawashima Shimodate (Extra) Hatonosu Minami-Furuya Naka-Urawa 33 Mito Line Nishi-Urawa 南浦和 Higashi-Urawa Higashi- Akatsuka Kori Ogose Musashi-Takahagi Musashi-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kawaguchi Kasama 武蔵浦和 Kawai Moro 20 Kawagoe Line Kita-Toda Warabi Shim-Misato Uchihara MitakeSawaiIkusabataFutamataoIshigamimaeHinatawadaMiyanohira 高麗川 Kita-Asaka Minami-oshigaya 友部 Ome - Toda Nishi-Kawaguchi K Komagawa Hachiko Line Yoshikawa Shishido Tomobe - Toda-Koen Kawaguchi - Misato - 14 Ome Line Higashi-Ome 4 Keihin-Tohoku- Line 23 Joban Line [Local Train]-Chiyoda Niiza - Ukimafunado 22 Iwama Kabe Higashi-Hanno 19 Saikyo- Line. -

CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION from Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network

Report CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION From Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXISTING REGIONAL RAIL NETWORK 10 THE VISION 26 BIDIRECTIONAL RUN-THROUGH SERVICE 28 EXPANDED SERVICE 29 SEAMLESS RIDER EXPERIENCE 30 SUPERIOR OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION 30 CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAM 31 VISION ANALYSIS 32 IMPLEMENTATION AND NEXT STEPS 47 KEY STAKEHOLDER IMPLEMENTATION ROLES 48 NEXT STEPS 51 APPENDICES 55 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decisions that we as a region make in the next five years will determine whether a more coordinated, integrated regional rail network continues as a viable possibility or remains a missed opportunity. The Capital Region’s economic and global Railway Express (VRE) and Amtrak—leaves us far from CAPITAL REGION RAIL NETWORK competitiveness hinges on the ability for residents of all incomes to have easy and Perryville Martinsburg reliable access to superb transit—a key factor Baltimore Frederick Penn Station in attracting and retaining talent pre- and Camden post-pandemic, as well as employers’ location Yards decisions. While expansive, the regional rail network represents an untapped resource. Washington The Capital Region Rail Vision charts a course Union Station to transform the regional rail network into a globally competitive asset that enables a more Broad Run / Airport inclusive and equitable region where all can be proud to live, work, grow a family and build a business. Spotsylvania to Richmond Main Street Station Relative to most domestic peer regions, our rail network is superior in terms of both distance covered and scope of service, with over 335 total miles of rail lines1 and more world-class service. -

Daiba Park to Monzen- 36 (No.3 Battery) Nakacho No.6 Battery Odaiba- Kaihin-Koen Tokyo Bay Daiba

Rainbow Bridge Waterbus (Odaiba-Kaihin-Koen) Daiba Park to Monzen- 36 (No.3 Battery) Nakacho No.6 battery Odaiba- Kaihin-Koen Tokyo bay Daiba Merpolitan Expressway Shiokaze Park Wangan line Metropolitan Expressway No.1 Museum of Maritime Science Waterbus Daiba Park (Fune-no-Kagakukan) Administrator ■ Tokyo Waterfront Group ●Location Daiba 1-chome, Minato Ward ●Contact Information Shiokaze Park Administration Office tel: 03-5500-0385 (1-2 Higashi-Yashio, Shinagawa-ku 135-0092) ●Transport 12-minute walk from Odaiba-Kaihin-Koen on Yurikamome (Shinbashi to Toyosu), 15-minute walk from Tokyo Teleport (Rinkai line) Water-bus: About 50-minute ride from Ryogoku or Kasai-Rinkai-Koen on Tokyo Mizube Cruising Line (tel: 03-5608-8869). Water-bus: 20-minute walk from Odaiba-Kaihin-Koen (20-minute ride from Hinode Pier on Tokyo Water Cruise)(tel: 0120-977-311). Daiba When the US fleet led by Commodore Perry arrived in Uraga in 1853 during the Bakumatsu (the end of Tokugawa shogunate), the shogunate No. 6 battery On the north side resides the remnants of the port made with stone. government did not have large ships to protect Edo from the attacks of foreign ships. More than the general citizenry, it was the shogunate that It can be viewed by climbing the bank of Daiba Park (the No. 3 battery). was surprised by the arrival of Perry’s back ships. It didn’t have any large ships to protect Edo from foreign at tack. So, the construction of daiba, or artillery batteries, was conceived. Of the 11 originally planned, only six were actually built off the shore of Shinagawa.