Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

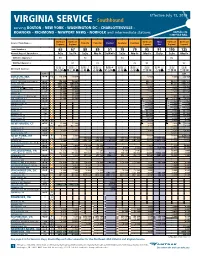

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Portrait of Peshawar

NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRI'IE RS CONSENT CVR-5 INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS I0 January 1991 Peshawar, Pakistan A Peshawar fruit and nut vendor displays hs wares. PORTRA I T OF PESHAWAR by Carol Rose A11ahu 21kbar (God is most great) cries one voice, then another, and another until the pre-dawn darkness is engulfed in cacophony that calls faithful Muslims to the first of five prayers they perform each day. As the sun hits the nearby Himalayan foothills, the air is filled with the crowing of roosters, the clip-clop of the horse- drawn tonga wagons, and the pop-popping of Kalishnakov rifles being fired toward the heavens. Morning sounds in one of the world's oldest cities reflect the spirit of Peshawar" its religious reverence, rustic beauty and atmosphere of violence. And in the back streets, bazaars and tea shops of this ancient cross-roads, a newcomer easily falls under the spell of the Asian subcontinent. Carol Rose is an ICWA fellow writing on the cultures of South and Central Asa. Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane-Rogers Foundation) has provided long-term fellowships to enable outstanding young adults to live outside the United States and write about international areas and issues. Endowed by the late Charles R. Crane, the Institute is also supported by contributions from like-minded individuals and foundations. CVR-5 2 GOD WILLING WE WILL LAND "Insha-allah (God Willing) we will soon be landing," announces the pilot of the Pakistan International Airlines propeller plane. The flight from Pakistan's capital city, Islamabad, to Peshawar has lasted less than an hour. -

Page 1 of 8 PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Emai

PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Email: [email protected] RESUME Summary Phil Craig has 50 years of experience in the rail transit and railroad field. My expertise is in planning, design, construction, and operation of heavy rail rapid transit systems (metros or subways), light rail transit systems, suburban or regional (commuter) rail systems, high-speed passenger railways, and main line passenger and freight railroads. My broad technical knowledge as a transportation planner and analyst encompasses a wide range of planning, operations, and management areas. I have held significant management positions with transport organizations serving large metropolitan areas in the United States, Great Britain and Greece, as well having been a consultant on rail projects in Canada, India, South Korea, Taiwan and Turkey. Education Bachelor of Science (Cum Laude), Public Utilities and Transportation, New York University, New York, New York, 1963 Professional Data Past Chairman (1973-76) and Committee Member (1972-80), Subcommittee on Federal Rules and Regulations Committee on Mobility for the Elderly and Handicapped American Public Transit Association, Washington, D.C., USA Member, Light Rail Transit Association, London, England Member, Light Rail Panel, New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers Experience Independent Transportation Consultant – March 2009 to July 2009 Project: Honolulu High Capacity Transit Corridor Project, Honolulu, O'ahu, Hawai'i Clients: Kamehameha Schools and Honolulu Chapter of American Institute of Architects Assignment: Analyze Potential for Use of Light Rail Transit Technology Roles: Consultant to Kamehameha Schools and Adviser to AIA Honolulu Prepared a Light Rail Transit Feasibility Report for Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate (the largest private landholder in the Hawaiian Islands). -

Manora Field Notes & Beyond: a Conversation With

Manora Field Notes & Beyond: A conversation with Naiza Khan In 2019, Naiza Khan became the first British-Pakistani artist to represent Pakistan for the country’s inaugural pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale. Titled Manora Field Notes, the multimedia archival project was inspired by the artist’s twelve years of expansive research and documentation of the maritime trade and histories she unearthed on the island of Manora, situated on the southern part of the Karachi Peninsula. From 1986–1987, Khan studied at Wimbledon College of Art, before going on to receive her BFA in printmaking and painting from the Ruskin School of Fine Art, Oxford. She recently graduated with an MA in Research Architecture from Goldsmiths’ Department of Visual Cultures. Khan’s work has been widely exhibited internationally, including the Kochi- Muziris Biennale (2016) and the Shanghai Biennale (2012), as well as in exhibitions such as ‘Desperately Seeking Paradise’, Art Dubai, UAE (2008); ‘Hanging Firse: Contemporary Art From Pakistan’, Asia Society, New York (2009); Manifesta 8, Murcia, Spain (2010); the Cairo Biennale, Egypt (2010); ‘Restore the Boundaries: The Manora Project’, Rossi & Rossi Gallery and Art Dubai, Dubai, UAE (2010); ); ‘Art Decoding Violence’, XV Biennale Donna, Ferrara, Italy, (2012); and ‘Set In A Moment Yet Still Moving’, Koel Gallery, Karachi (2017). The artist has been selected for a number of fellowships and residencies, including Gasworks, London; the Rybon Art Centre, Tehran; and the Institute for Comparative Modernities, Cornell University, among others. As a founding member and long-time coordinator of the Vasl Artists’ Collective in Karachi, Khan has worked to foster art in the city and participated in a series of innovative art projects in partnership with other workshops in the region and beyond, such as the Khoj International Artists’ Association, New Delhi; the Britto Arts Trust, Dhaka, Bangladesh; the Sutra Art Foundation, Kathmandu, Nepal; and the Theertha International Artists’ Collective, Colombo, Sri Lanka. -

JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure Of

Republic of India Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure of Mumbai Metro Line 3 Project in India Final Report October 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan International Consultants for Transportation Co., Ltd. PADECO Co., Ltd. 4R Metro Development Co., Ltd JR 15-046 Table of Contents Chapter 1 General issues for the management of urban railways .............................. 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Management of urban railways ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Construction of urban railways ...................................................................................... 12 1.4 Governing Structure ........................................................................................................ 17 1.5 Business Model ................................................................................................................. 21 Chapter 2 Present situation in metro projects ............................................................ 23 2.1 General .............................................................................................................................. 23 2.2 Metro projects in the world ............................................................................................. 23 2.3 Summary........................................................................................................................ -

ESCAP PPP Case Study #4

Public-Private Partnerships Case Study #4 Land Value Capture Mechanism: The Case of the Hong Kong MTR by Mathieu Verougstraete and Han Zeng (July 2014) This case study presents how a property development programme has been used to finance Hong Kong’s public transport system and discusses whether this model is replicable in other countries. LAND VALUE CAPTURE MECHANISM includes railways, trams, buses, minibuses, taxis and ferries.2 More than 90 per cent of Land value capture mechanisms follow the all motorized trips are by public transport, the 3 basic logic that enhanced accessibility to highest market share in the world. attractive and efficient transport systems adds value to land and real estate. To achieve these impressive results, major investments had to be made in public This value addition has been confirmed by transport systems. A key actor in the sector several researches. For example, research has been the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway indicates that housing price premiums in Corporation (MTRC), established in 1975 to Hong Kong are in the range of 5 to 17 per provide metro services. Its entire system now cent for units in proximity to a railway. This stretches 218.2 km and has 84 stations and premium can even exceed 30 per cent if 68 light rail stops. properties incorporate transit-oriented design, such as structures that facilitate pedestrian The sections below will describe how MTRC access to commercial amenities or provide has managed to mobilize siginificant financial pathways that are connected with stations.1 resources for its network development. As this value premium results from public MTRC BUSINESS MODEL investments, it is reasonable for public authorities to try to capture the surplus. -

CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION from Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network

Report CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION From Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXISTING REGIONAL RAIL NETWORK 10 THE VISION 26 BIDIRECTIONAL RUN-THROUGH SERVICE 28 EXPANDED SERVICE 29 SEAMLESS RIDER EXPERIENCE 30 SUPERIOR OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION 30 CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAM 31 VISION ANALYSIS 32 IMPLEMENTATION AND NEXT STEPS 47 KEY STAKEHOLDER IMPLEMENTATION ROLES 48 NEXT STEPS 51 APPENDICES 55 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decisions that we as a region make in the next five years will determine whether a more coordinated, integrated regional rail network continues as a viable possibility or remains a missed opportunity. The Capital Region’s economic and global Railway Express (VRE) and Amtrak—leaves us far from CAPITAL REGION RAIL NETWORK competitiveness hinges on the ability for residents of all incomes to have easy and Perryville Martinsburg reliable access to superb transit—a key factor Baltimore Frederick Penn Station in attracting and retaining talent pre- and Camden post-pandemic, as well as employers’ location Yards decisions. While expansive, the regional rail network represents an untapped resource. Washington The Capital Region Rail Vision charts a course Union Station to transform the regional rail network into a globally competitive asset that enables a more Broad Run / Airport inclusive and equitable region where all can be proud to live, work, grow a family and build a business. Spotsylvania to Richmond Main Street Station Relative to most domestic peer regions, our rail network is superior in terms of both distance covered and scope of service, with over 335 total miles of rail lines1 and more world-class service. -

December 2013 405 Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd

Appendix IV Scheduled Banks’ Islamic Banking Branches in Pakistan As on 31st December 2013 Al Baraka Bank -Lakhani Centre, I.I.Chundrigar Road Vehari -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, D.H.A. (Pakistan) Ltd. (108) -Phase-II, D.H.A. -Provincial Trade Centre, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Askari Bank Ltd. (38) Main University Road Abbottabad -S.I.T.E. Area, Abbottabad Arifwala Chillas Attock Khanewal Faisalabad Badin Gujranwala Bahawalnagar Lahore (16) Hyderabad Bahawalpur -Bank Square Market, Model Town Islamabad Burewala -Block Y, Phase-III, L.C.C.H.S Taxila D.G.Khan -M.M. Alam Road, Gulberg-III, D.I.Khan -Main Boulevard, Allama Iqbal Town Gujrat (2) Daska -Mcleod Road -Opposite UBL, Bhimber Road Fateh Jang -Phase-II, Commercial Area, D.H.A. -Near Municipal Model School, Circular Gojra -Race Course Road, Shadman, Road Jehlum -Block R-1, Johar Town Karachi (8) Kasur -Cavalry Ground -Abdullah Haroon Road Khanpur -Circular Road -Qazi Usman Road, near Lal Masjid Kotri -Civic Centre, Barkat Market, New -Block-L, North Nazimabad Minngora Garden Town -Estate Avenue, S.I.T.E. Okara -Faisal Town -Jami Commercial, Phase-VII Sheikhupura -Hali Road, Gulberg-II -Mehran Hights, KDA Scheme-V -Kabeer Street, Urdu Bazar -CP & Barar Cooperative Housing Faisalabad (2) -Phase-III, D.H.A. Society, Dhoraji -Chiniot Bazar, near Clock Tower -Shadman Colony 1, -KDA Scheme No. 24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal -Faisal Lane, Civil Line Larkana Kohat Jhang Mansehra Lahore (7) Mardan -Faisal Town, Peco Road Gujranwala (2) Mirpur (AK) -M.A. Johar Town, -Anwar Industrial Complex, G.T Road Mirpurkhas -Block Y, Phase-III, D.H.A. -

(Pvt) Ltd. Shop No. 01, Ground

Network Position of Exchange Companies and Exchange Companies of 'B' Category As on September 27, 2021 S# Name of Company Address Outlet Type City District Province Remarks Shop No. 01, Ground Floor, Opposite UBL, Mirpur Chowk, 1 Ravi Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Bhimber Bhimber AJK Active Mirpur Road, Bhimber, Azad Jammu & Kashmir Shop No. 01, Plot No. 67, Junaid Plaza, College Road, Near 2 Royal International Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Maqbool Butt Shaheed Chowk, Tehsil Dadyal, Distt. Mirpur Branch Dadyal Dadyal AJK Active Azad Kashmir Office No. 05, Lower Floor, Deen Trade Centre, Shaheed 3 Sky Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active Chowk, Kotli, AJK. Shop # 3&4 Gulistan Plaza Pindi Road Adjacent to NADRA 4 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active off AJK Shop # 1,2,3 Ch Sohbat Ali shopping center near NBP main 5 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Chaksawari Mirpur AJK Active bazar Chaksawari Azad Kashmir Shop No. 119-A/3, Sub Sector C/2, Quaid-e-Azam Chowk, 6 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Dadyal Mirpur AJK Active Mirpur, District Mirpur, Azad Kashmir 7 Dollar East Exchange Company (Pvt.) Ltd. Shop # 39-40, Muhammadi Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Shop No. 1-A, Ground Floor, Kalyal Building, Naik Alam 8 HBL Currency Exchange (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Road, Chowk Shaheedan, Mirpur, AJK Sector A-5, Opp. NBP Br., Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Azad 9 NBP Exchange Company Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Kashmir. -

China's Newest

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com SEPTEMBER 2017 NO. 957 CHINA’S NEWEST LRT: WIRE-FREE IN WUHAN Is there a crisis in maintaining US rail infrastructure? Sidi Bel Abbès: Algeria’s 4th tramway Essen and Mülheim merge operations End of the road for Kramatorsk’s trams UK Conference Sydney 09> £4.40 ‘Follow the money, Celebrating the life of sell the benefits’ a once-great tramway 9 771460 832050 4 October 2017 Entries open now! t: +44 (0)1733 367600 @ [email protected] www.lightrailawards.com CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association SEPTEMBER 2017 Vol. 80 No. 957 www.tautonline.com 341 EDITORIAL EDITOR Simon Johnston E-mail: [email protected] 13 Orton Enterprise Centre, Bakewell Road, Peterborough PE2 6XU, UK 324 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Tony Streeter E-mail: [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] NEWS EDITOR John Symons 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS 316 Tony Bailey, James Chuang, Paul Nicholson, Richard Felski, Ed Havens, Bill Vigrass, Andrew Moglestue, NEWS 324 S YSTEMS FACTFILE: BOGESTRA 345 Mike Russell, Nikolai Semyonov, Vic Simons, Herbert New tramlines in Sidi Bel Abbès and Neil Pulling explores the Ruhr network that Pence, Alain Senut, Rick Wilson, Thomas Wagner Wuhan; Gold Coast LRT phase two ‘90% uses different light rail configurations to PDTRO UC ION Lanna Blyth complete’; US FTA plan to reduce barriers to cover a variety of urban areas. -

Branch Directory

Dubai Islamic Bank - Branch Directory Abbottabad S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Khyber 1 31 Abbottabad CB 306/4, Lala Rukh Plaza, Mansehra Road, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342239-41 Ground Floor, Shop Nos.12 & 13, Mamu Jee Market, Opp GPO, Cantt Khyber 2 161 Abbottabad 2 Bazaar, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342394 Attock S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Plot No B-1-63, A Block, Khan Plaza, Fawara Chowk, Civil Bazaar, Attock. 3 73 Attock Punjab. Punjab 057-2702054-6 Mehria Town Housing Scheme, Phase 1, Shop No. 25 + 39, Block - A, Kamra 4 187 Mehria Road - Attock Punjab Bahawalpur S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Model Town Plot No 12.B, Khewat No 148,Khatooni No.246,General Officer Colony, 062-2889951-3, 5 71 Bahawalpur Model Town B, Bahawalpur,Punjab. Punjab 2889961-3 Burewala S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number 439/EB, Block C, Al-Aziz Super Market, College Road, Burewala. Vehari 6 95 Burewala District, Punjab. Punjab 067-3772388 Chakwal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, No. 1636, Khewat 323, Opposite Main PTCL Office Main 7 172 Chakwal Talagang Road, Chakwal District, Punjab. Punjab 054-3544115 Chaman S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Haji Ayub Plaza, Plot No. Mall Road, Chaman.Killa Abdullah 8 122 Chaman District, Balochistan . Balochistan 0826-61806-61812 Dadyal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Khasra No. 552, Moza Mandi, Kacheri Road, Dadyal, District Azad Jammu & 9 120 Dadyal Mirpur Azad Jammu Kashmir.