Address by Alexander Berkman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman Emma Goldman May 1906 ON the 18th of this month the workhouse at Hoboken, Pa., will open its iron gates for Alexander Berkman. One buried alive for fourteen years will emerge from his tomb. That was not the intention of those who indicted Berkman. In the kindness of their Christian hearts they saw to it that he be sentenced to twenty-one years in the penitentiary and one year in the workhouse, hoping that that would equal a death penalty, only with a slow, refined execution. To achieve the feat of sending a man to a gradual death, the authorities of Pittsburg at the command of Mammon trampled upon their much-beloved laws and the legality of court proceedings. These laws in Pennsylvania called for seven[23] years imprisonment for the attempt to kill, but that did not satisfy the law-abiding citizen H. C. Frick. He saw to it that one indictment was multiplied into six. He knew full well that he would meet with no opposition from petrified injustice and the servile stupidity of the judge and jury before whom Alexander Berkman was tried. In looking over the events of 1892 and the causes that led up to the act of Alexander Berkman, one beholds Mammon seated upon a throne built of human bodies, without a trace of sympathy on its Gorgon brow for the creatures it controls. These victims, bent and worn, with the reflex of the glow of the steel and iron furnaces in their haggard faces, carry their sacrificial offerings to the ever-insatiable monster, capitalism. -

Sasha and Emma the ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF

Sasha and Emma THE ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF ALEXANDER BERKMAN AND EMMA GOLDMAN PAUL AVRICH KAREN AVRICH SASHA AND EMMA SASHA and EMMA The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich Th e Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, En gland 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Karen Avrich. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Avrich, Paul. Sasha and Emma : the anarchist odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman / Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich. p . c m . Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 06598- 7 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Berkman, Alexander, 1870– 1936. 2. Goldman, Emma, 1869– 1940. 3. Anarchists— United States— Biography. 4 . A n a r c h i s m — U n i t e d S t a t e s — H i s t o r y . I . A v r i c h , K a r e n . II. Title. HX843.5.A97 2012 335'.83092273—dc23 [B] 2012008659 For those who told their stories to my father For Mark Halperin, who listened to mine Contents preface ix Prologue 1 i impelling forces 1 Mother Rus sia 7 2 Pioneers of Liberty 20 3 Th e Trio 30 4 Autonomists 43 5 Homestead 51 6 Attentat 61 7 Judgment 80 8 Buried Alive 98 9 Blackwell’s and Brady 111 10 Th e Tunnel 124 11 Red Emma 135 12 Th e Assassination of McKinley 152 13 E. G. Smith 167 ii palaces of the rich 14 Resurrection 181 15 Th e Wine of Sunshine and Liberty 195 16 Th e Inside Story of Some Explosions 214 17 Trouble in Paradise 237 18 Th e Blast 252 19 Th e Great War 267 20 Big Fish 275 iii -

The Bolshevik Myth (Diary 1920–22) – Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman The Bolshevik Myth (Diary 1920–22) 1925 Contents Preface . 3 1. The Log of the Transport “Buford” . 5 2. On Soviet Soil . 17 3. In Petrograd . 21 4. Moscow . 29 5. The Guest House . 33 6. Tchicherin and Karakhan . 37 7. The Market . 43 8. In the Moskkommune . 49 9. The Club on the Tverskaya . 53 10. A Visit to Peter Kropotkin . 59 11. Bolshevik Activities . 63 12. Sights and Views . 69 13. Lenin . 75 14. On the Latvian Border . 79 I . 79 II . 83 III . 87 IV . 92 15. Back in Petrograd . 97 16. Rest Homes for Workers . 107 17. The First of May . 111 18. The British Labor Mission . 115 19. The Spirit of Fanaticism . 123 20. Other People . 131 21. En Route to the Ukraina . 137 1 22. First Days in Kharkov . 141 23. In Soviet Institutions . 149 24. Yossif the Emigrant . 155 25. Nestor Makhno . 161 26. Prison and Concentration Camp . 167 27. Further South . 173 28. Fastov the Pogromed . 177 29. Kiev . 187 30. In Various Walks . 193 31. The Tcheka . 205 32. Odessa: Life and Vision . 209 33. Dark People . 221 34. A Bolshevik Trial . 229 35. Returning to Petrograd . 233 36. In the Far North . 241 37. Early Days of 1921 . 245 38. Kronstadt . 249 39. Last Links in the Chain . 261 2 Preface Revolution breaks the social forms grown too narrow for man. It bursts the molds which constrict him the more solidified they become, and the more Life ever striving forward leaves them.In this dynamic process the Russian Revolution has gone further than any previous revolution. -

Published Essays and Pamphlets "The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman" by Leonard D. Abbott

Published Essays and Pamphlets "The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman" by Leonard D. Abbott When Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, charged with conspiracy to defeat military registration under the conscription law, were sentenced by Judge Julius M. Mayer, on July 9, 1917, to serve two years in prison, to pay fines of $10,000 each, and to be probably deported to Russia at the expiration of their prison terms, United States Marshal McCarthy said: "This marks the beginning of the end of Anarchism in New York." But Mr. McCarthy is mistaken. The end of Anarchism will only be in sight when Liberty itself is dead or dying, and Liberty, as Walt Whitman wrote in one of his greatest poems, is not the first to go, nor the second or third to go,--"it waits for all the rest to go, it is the last." When there are no more memories of heroes and martyrs, And when all life and all the souls of men and women are discharged from any part of the earth, Then only shall liberty or the idea of liberty be discharged from that part of the earth, And the infidel come into full possession. THE ARREST Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were arrested on June 15, at 20 East 125th Street, New York. At the time of the arrival of the Marshal and of his minions, late in the afternoon, Miss Goldman was in the room which served as the office of the No-Conscription League and of MOTHER EARTH. Berkman was upstairs in the office of THE BLAST. -

Here Is Louise Michel This, People Could Say She Is a Pathological Case

Number 93-94 £1 or two dollars Mar. 2018 Here is Louise Michel this, people could say she is a pathological case. But there are thousands like her, millions, none of whom gives a damn about authority. They all repeat the battle cry of the Russian revolutionaries: land and freedom! Yes, there are millions of us who don’t give a damn for any authority because we have seen how little the many-edged tool of power accomplishes. We have watched throats cut to gain it. It is supposed to be as precious as the jade axe that travels from island to island in Oceania. No. Power monopolized is evil. Who would have thought that those men at the rue Hautefeuille who spoke so forcefully of liberty and who denounced the tyrant Napoleon so loudly would be among those in May 1871 who wanted to drown liberty in blood? [1] Power makes people dizzy and will always do so until power belongs to all mankind. Note 1, A swipe at moderate republicans who opposed the [Louise Michel (1830-1905) was back in prison Paris Commune: ‘Among the people associated with (again) in the 1880s when she wrote her memoirs the [education centre on] rue Hautefeuille was Jules (after the 1883 Paris bread riot). They were published Favre. At this time he was a true republican leader, but in February 1886. In this extract she looks back at her after the fall of Napoleon III he became one of those younger self, just before the Paris Commune of 1871.] who murdered Paris. -

Anarchist Movement Today

The Anarchist Movement Today Alexander Berkman January, 1934 The history of human civilization is not a straight, continuously forward-moving line. Itsdia- gram is a zigzag, now advancing, now retreating. Progress is measured by the distance separating man from his primitive conditions of ignorance and barbarism. At the present time mankind seems to be on the retreat. A wave of reaction is sweeping the countries of Europe; its effects and influence are felt all over the world. There is fascism inItaly, Hitlerism in Germany, despotism in Russia, destructive dictatorship in other countries. Every progressive and radical party, every revolutionary movement has suffered from the present reaction. In some countries they had been entirely crushed; in others their activities are paralyzed for the time being. It is the essence of all tyrannies and dictatorship, of whatever name or color, to suppress and eradicate everything that stands in the wake of its exclusive domination and triumph. Thus in Russia, for instance, the active anarchist elements (as also the Mensheviki and the Socialist-Revolutionaries) have either been shot or are being kept in prison and exile for indefinite periods. A similar fate has overtaken them in Italy and Germany. But though anarchism has suffered from the reaction, as have all other liberal and revolution- ary movements, it is fundamentally and essentially lost much less than the socialist parties. The reason for it is to be found in certain causes underlying the worldwide reaction. It is generally believe that the war, with its brutalization of man and destruction of higher values, the financial bankruptcy which followed, and the great crisis have brought about the present situation. -

Anarchist Theory, Critical Pedagogy, and Radical Possibilities Abraham P

The time for action is now! Anarchist theory, critical pedagogy, and radical possibilities Abraham P. DeLeon University of Connecticut, USA "When the rich assemble to concern themselves with the business of the poor it is called charity. When the poor assemble to concern themselves with the business of the rich it is called anarchy." Paul Richard Rudolf Rocker (1989), a 19th century anarchist, proclaimed that anarchist theory was separate from a state driven, hierarchical socialism in that, “…when a revolutionary situation arises they [the people] will be capable of taking the socio-economic organism into their own hands and remaking it according to Socialist principles” (p. 86). Arising from the idea that small cooperatives of people could form without the need of a coercive and hierarchical state, Rocker envisioned a society that was based on cooperation, community participation, and mutual aid. Rocker’s vision of society, and other anarchist-communist (or anarcho-syndicalist) theorists, is especially relevant in a time that has seen a “war on terror” that was not supported by the global community, the rollback of civil liberties with legislation such as The Patriot Act, and educational laws such as No Child Left Behind that are focusing on narrowly-defined “standards” for public schooling. Historically, anarchists have been marginalized in academic literature, but have still been involved in radical political struggles throughout the world (Bowen, 2005; Chomsky, 2005; Day, 2004; Goaman, 2005). Within radical circles, anarchist literature has begun to gain popularity over the past several years (Bowen & Purkis, 2005). An anarchist presence can be seen in the anti-globalization movement, the “Black Bloc” protests against the IMF and World Bank, and other smaller, localized resistance efforts such as Anti-Racist Action (ARA) and Food Not Bombs (Bowen, 2005; Goaman, 2005). -

Insurrection Vs. Organization –

domination of the student assemblies by the political parties, other anarchists can Insurrection vs. Organization: provide a bridge for more people to be involved, make overtures for solidarity to Reflections from Greece on a Pointless Schism other sectors of society, and strengthen the movement that has provided a basis Peter Gelderloos for the possibility of change. If these two types of anarchists work together, the insurrectionary ones are less likely to be disowned as outsiders and isolated, thrown “I consider it terrible that our movement, everywhere, is degenerating into a swamp of to the police, because they have allies in the very middle of the movement. And petty personal quarrels, accusations, and recriminations. There is too much of this rotten when the state approaches the organized anarchists in the movement in an attempt thing going on, particularly in the last couple of years.” to negotiate, they are less likely to give in because they have friends outside the --out of a letter from Alexander Berkman to Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer, in organization holding them accountable and reminding them that power is in the 1928. Emma Goldman adds the postscript: “Dear children. I agree entirely with Sasha. streets. I am sick at heart over the poison of insinuations, charges, accusations in our ranks. If Similar lessons on the potential compatibility of these two approaches that will not stop there is no hope for a revival of our movement.” can be drawn from anarchist history in Spain of ’36 or France of ’68. Both of these episodes ultimately showed that insurrection is a higher form of struggle, that wait- Fortunately, most anarchists in the US avoid any ideological orthodoxy and shun ing for the right moment is reactionary, that bureaucratic organizations such as the sectarian divides. -

VIII with the End of the Civil War, America Passed Over a Great

VIII With the end of the Civil War, America passed over a great watershed. After 1865, the government grew larger and ever more powerful; agricul ture became less significant than industry. Cities such as New York, Phila delphia, Chicago, and Boston grew to mammoth size; the frontier line between white and Indian civilizations dissolved. Railroads spanned the continent; new industries such as steel, rubber, and oil grew ominously larger. The world Spooner was born into had changed. He welcomed the inven tions, the expansion, and the progress. The persisting poverty, he believed, could be eliminated through his New System of Paper Currency (1861). Virtually every occasion provided an opportunity for him to expand his economic ideas. Reconstruction, the lawlessness in the Montana gold fields, a fire in Boston, discontent in the West, and the severe economic depression from 1873 to 1879-all these elicited letters and pamphlets from him. With the war barely ended, Spooner submitted an article to the leading periodical in the South, DeBow's Review-"Proposed Banking System for the South" (August, 1866). Here he claimed that adoption of his system would instantly double the value of all real property in the South. "It would at once establish credit in the North and in England, and enable her [the South] to supply herself with everything she needs." Social ends would be realized, too, because "the benefits of this increased wealth, in dustry and credit would not be monopolized by the whites, but would be liberally shared in by the blacks as a necessary result from the increased demand for their labor." 1 1 Lysander Spooner, "Proposed Banking System for the South," DeBow's Review, new series, II (August, 1866), 155. -

Lysander Spooner, Lifestyle Anarchism, and Jury Nullification

LYSANDER SPOONER, LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM, AND JURY NULLIFICATION by edward john skrod A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in Philosophy Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2011 i LYSANDER SPOONER, LIFESTYLE ANARCHISM, AND JURY NULLIFICATION by edward john skrod This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Daniel R. White, and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Daniel R. White ___________________________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ___________________________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College _______________ Date ii ABSTRACT Author: edward john skrod Title: Lysander Spooner, Lifestyle Anarchism, and Jury Nullification Institution: Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Daniel R. White Degree: Bachelors of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences Concentration: Philosophy Year: 2011 Individual anarchism, a social movement of the early nineteenth century, was founded on the principles of self-sovereignty and individualism. One such anarchist, Lysander Spooner, argues in “Vices are not Crimes” that vices should not be criminalized by the State. To do so, “deprive*s+ every man of his… liberty to pursue his own happiness.”1 I argue that Spooner’s essay lays the foundation for “lifestyle anarchism,” the doctrine that all the affairs of human beings within the domain of their lifestyle choices (provided they do not harm the person or property of another), should be managed by individuals or voluntary associations. -

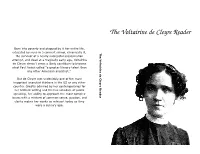

The Voltairine De Cleyre Reader

The Voltairine de Cleyre Reader Born into poverty and plagued by it her entire life, educated by nuns in a convent school, chronically ill, T h the survivor of a nearly successful assassination e V attempt, and dead at a tragically early age, Voltairine o l t de Cleyre doesn't seem a likely candidate to become a i r what Paul Avrich called "a greater literary talent than i n any other American anarchist." e d e C But de Cleyre was undeniably one of the most l e y important anarchist thinkers in the US or any other r e country. Greatly admired by her contemporaries for R e her brilliant writing and tireless schedule of public a d speaking, her ability to approach the most complex e r issues with a mixture of common sense, passion, and clarity makes her works as relevant today as they were a century ago. 2004 AK Press anticopyright ISBN: 9781902593876 Palczewski, Catherine Helen (1995) Voltairine de Cleyre: Sexual Slavery and Sexual Pleasure in the Nineteenth Century. NWSA vol.7, Fall 95. Parker, S.E. Voltairine de Cleyre: Priestess of Pity and Vengeance, Freedom (London), April 29, 1950. Perlin, Terry M. Anarchism and Idealism: Voltairine de Cleyre, LaborHistory, xiv (Fall 1973), 506-20. Rexroth, Kenneth. Again at Waldheim (poem), Retort (Bearsville, NY), Winter 1942. Starrett, Walter [W.S. Van Valkenburgh]. Untitled manuscript on Voltairine de Cleyre, TABLE OF CONTENTS Ishill Collection, Harvard. Biographies Stein, Gordon (1995) Voltairine De Cleyre: The American Rationalist Volume 39, by Sharon Presley 1 Number 6. by Sara Baase 6 Voltairine de Cleyre, Freedom (London), August 1912. -

•'I Must First Take Stock of My Own Self:" the Individual & the Not-Mass in Emma Goldman's Anarchism

•'I MUST FIRST TAKE STOCK OF MY OWN SELF:" THE INDIVIDUAL & THE NOT-MASS IN EMMA GOLDMAN'S ANARCHISM A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (c) Copyright by Laura Greenwood 2011 Theory, Culture and Politics M.A. Graduate Program October 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your Tile Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81100-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81100-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre im primes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.