Comprehending China's Stance in Global Financial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle Over Taxing Offshore Accounts

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2012 The Battle Over Taxing Offshore Accounts Itai Grinberg Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1786 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2497998 60 UCLA L. Rev. 304 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Taxation-Transnational Commons, and the Tax Law Commons The Battle Over Taxing Offshore Accounts Itai Grinberg EVIEW R ABSTRACT The international tax system is in the midst of a contest between automatic information reporting and anonymous withholding models for ensuring that nations have the ability to LA LAW LA LAW tax offshore accounts. At stake is the extent of many countries’ capacity to tax investment UC income of individuals and profits of closely held businesses through an income tax in an increasingly financially integrated world. Incongruent initiatives of the European Union, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Switzerland, and the United States together represent an emerging international regime in which financial institutions act to facilitate countries’ ability to tax their residents’ offshore accounts. The growing consensus that financial institutions should act as cross-border tax intermediaries represents a remarkable shift in international norms that has yet to be recognized in the academic literature. The debate, however, is about how financial institutions should serve as cross-border tax intermediaries, and for which countries. Different outcomes in this contest portend starkly different futures for the extent of cross-border tax administrative assistance available to most countries. -

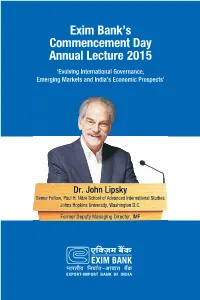

Exim Bank's Commencement Day Annual Lecture 2015

Exim Bank’s Commencement Day Annual Lecture 2015 ‘Evolving International Governance, Emerging Markets and India’s Economic Prospects’ Dr. John Lipsky Senior Fellow, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University, Washington D.C. Former Deputy Managing Director, IMF 101 This is the Thirtieth Exim Bank Commencement Day Annual Lecture, delivered at the Y. B. Chavan Centre, Mumbai - 400 021 on Monday, March 23, 2015. No part of this Lecture may be reproduced without the permission of Export-Import Bank of India. The views and interpretations in this document are those of the author and not ascribable to Export-Import Bank of India. Evolving International Governance, Emerging Markets and India’s Economic Prospects Dr. John Lipsky Senior Fellow Foreign Policy Institute The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University Washington, DC I’m honoured to be speaking today at this important event sponsored by EXIM Bank - an institution that is playing a key role in promoting India’s trading relationships with partners around the world - and I would like to thank the management of EXIM for the opportunity to be here. Of course, EXIM Bank’s kind invitation to be the 2015 Commencement Speaker led me to look back at the institution’s history. I found it somewhat surprising that the institution commenced operations just 33 years ago. Perhaps the promotion of India’s international commercial relations previously hadn’t seemed so central to India’s future progress and prosperity, as it does today. Of course, it is sobering, daunting, but also amazing and energizing to realize how much has changed in just that relatively brief span since EXIM’s founding. -

Insights for Intra-Party Tensions?

Hong Kong as a proxy battlefield Insights for Intra-Party tensions? Zhang Xiaoming 张晓明, the director of the State Council Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office 国务 院港澳办, was replaced a few days ago, as vice-director of the small leading group of the same name, by the current Minister of Public Security, Zhao Kezhi 赵克志. That said, it seems Hong Kong’s issues run deeper than just a few personnel appointments. Is the special administrative zone becoming a proxy battleground for opposing political forces inside the Party? The timeline and people involved suggest that parts of the ongoing crisis might have been made by design by outgoing political networks amid the anti-corruption campaign. From the selection of Carrie Lam 林郑月娥, the underpinnings of the Hong Kong and Macau affairs system, to the bid for the London Stock Exchange, there is more than meets the eye. The “Manchurian” Candidate and the Jiangpai From the beginning, the opinion was that Madame Lam would be a short-live replacement for Liang Zhenying 梁振英. Carrie Lam, who actually joined the protest – even for a brief moment – for universal suffrage back in 2014, stayed close to the negotiation with Beijing, unlike some of her counterparts who were refused entry in Shenzhen back in 2015. She then became one of the favorite faces of the administration, especially in late 2016, when Liang Zhenying1 announced he would not be running for re-election. Liang, a representative of the “old regime” – associated with both Zeng Qinghong 曾庆红2 and Zhang Dejiang 张德江, was creating issues leading to the deterioration of the situation in Hong Kong (i.e. -

Rule of Law and Its Effect on Chinese Economic Development

Al WASATH Jurnal Ilmu Hukum Volume 2 No. 1 April 2021: 41-57 RULE OF LAW AND ITS EFFECT ON CHINESE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Roziqin Guanghua Law School, Zhejiang University, China Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT China's economic growth during the Covid-19 pandemic was impressive because it did not fell into recession. China's government has become a role model for facing Covid-19 outbreaks. China is now the world's wealthiest country, if we see its Gross Domestic Product from Purchasing Power Parity (GDP-PPP). China's position as the number one globally is faster than Jacques's prediction in 2009 that it will happen in 2050. For China, which does not implement liberal democracy, the writer hypothesizes that the reasonable choice to develop the economy is state-driven development through the rule of law. At present, the rule of law has become a daily conversation of the Chinese people. However, there are still many outsiders who doubt China has and applies the rule of law. It happens because China implements the rule of law with Chinese characteristics. This research will study the rule of law with Chinese characteristics, China's effort to implement the rule of law, and the rule of law on China's economy. This study uses a qualitative descriptive approach to explain the rule of law with Chinese characteristics. It will analyze the rule of law concept and its effect on China's economy. China applies the rule of law with Chinese characteristics based on Chinese traditions, which are heavily influenced by Confucius's teachings and prioritize obligations rather than rights. -

FINANCIAL CRISIS and LEGITIMACY of GLOBAL ACCOUNTING STANDARDS Masaki Kusano Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University Kusa

FINANCIAL CRISIS AND LEGITIMACY OF GLOBAL ACCOUNTING STANDARDS Masaki Kusano Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University [email protected] ∗ Masatsugu Sanada Graduate School of Business, Osaka City University [email protected] May, 2013 ∗ Corresponding author FINANCIAL CRISIS AND LEGITIMACY OF GLOBAL ACCOUNTING STANDARDS ABSTRACT Purpose : to examine and clarify a mechanism of global accounting standard-setting and accounting regulation, especially to investigate the legitimation crises of global accounting standards and their restoration process focusing on the IASB’s response to the financial crisis. Methodology : institutional theory and an analytical framework of ‘decoupling, compromises, and systematic dominance’ Findings : We find that the IASB decoupled its regular due process in order to maintain the endorsement mechanisms in the EU and avoid a further carve-out. To reconcile the concerns about the IASB’s governance from the U.S. and the outside of Europe, the IASB established the monitoring board with compromising its expertise principle laying weight on independence with the request for enhancing its accountability. We also find that the IASB systematically put a dominance position to the needs of the EU as the biggest customer. Originality/value : We show the complicated mechanism of accounting standard-setting which the mere debates of the politicization of accounting could not reveal, and clarify that the legitimacy of organization, procedure, and its outputs could not exist stand-alone, but mutually prerequisite or exist with reflexivity. This study extends our knowledge of global financial regulations and our discussion offers numerous suggestions to globalization, especially the IASB’s roles in the globalization of financial regulations, and regulatory forum or network centered on the IASB. -

China–Africa and an Economic Transformation OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, SPi China–Africa and an Economic Transformation OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, SPi Praise for the book ‘This book’s accessible up-to-date assessment on the evolving trade and invest- ment relations between China and Africa is a welcome contribution to a field that is under-studied. The asymmetry in Africa-China relations is recognised and honestly addressed, including insights into governance arrangements. Lin and Oqubay’s book is academically rigorous, and also offers immensely practical guidance to Chinese and African stakeholders on how to build this partnership going forward.’ Dr Miriam Altman, PhD, Commissioner in the South African National Planning Commission ‘This is an extremely important volume. In the chatter on China and Africa, the Chinese and Africans are the very ones often left out. The editors them- selves represent a departure from “being spoken to” by a Western world with its own distinct interests. They have assembled a set of chapters of deep insights into collaboration in specific countries and which speak to a complex situation that indicates a changed world because of China and Africa.’ Stephen Chan OBE, Professor of World Politics, SOAS University of London ‘This book comes at a critical moment in China-Africa relations, as both sides explore ways to reach their partnership potential. The 2018 FOCAC Beijing Summit launched an ambitious cooperation agenda in support of Africa’s development, as encapsulated in Agenda 2063. We also agreed to advance shared priorities on -

The Judges 2017 FT & Mckinsey Business Book of the Year Award

By continuing to use this site you consent to the use of cookies on your device as described in our cookie policy unless you have disabled them. You can change your cookie settings at any time but parts of our site will not function correctly without them. Business books The judges 2017 Lionel Barber, FT editor, chairs our panel of experts FT & McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award YESTERDAY LIONEL BARBER Editor, Financial Times Lionel Barber is the editor of the Financial Times. Since his appointment in 2005, Barber has helped solidify the FT’s position as one of the first publishers to successfully transform itself into a multichannel news organisation. During Barber’s tenure, the FT has won numerous global prizes for its journalism, including Newspaper of the Year, Overseas Press Club, Gerald Loeb and Society of Publishers in Asia awards. Barber has co-written several books and has lectured widely on foreign policy, transatlantic relations, European security and monetary union in the US and Europe and appears regularly on TV and radio around the world. As editor, he has interviewed many of the world’s leaders in business and politics, including: US President Barack Obama, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany and President of Iran Hassan Rouhani. Barber has received several distinguished awards, including the St George Society medal of honour for his contribution to journalism in the transatlantic community. He serves on the Board of Trustees at the Tate and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. MITCHELL BAKER Executive chairwoman, Mozilla Mitchell Baker co-founded the Mozilla Project to support the open, innovative web and ensure it continues offering opportunities for everyone. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:19:39Z ASIEN 128 (Juli 2013), S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Existing and emerging powers in the G20: the case of East Asia Author(s) Duggan, Niall; Tiberghien, Yves Publication date 2013-07 Original citation Duggan, N. and Tiberghien, Y. (2013) 'Existing and emerging powers in the G20: the case of East Asia', Asien, 128, pp. 28-44. Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://asienforschung.de/wp- version content/uploads/2014/05/DGA_MV_2013_Konferenzbericht.pdf Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, German Association for Asian Studies. Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/3567 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:19:39Z ASIEN 128 (Juli 2013), S. 28–44 Existing and Emerging Powers in the G20: The Case of East Asia Yves Tiberghien and Niall Duggan Abstract Over the last twenty years, global financial integration and global financial volatility have greatly increased. The 2008 crisis represented a peak in the vulnerability of all countries around the world with regard to global financial volatility. In response to this volatility and as the first line of defense, states have used a growing array of domestic tools: monetary policy, fiscal policy, financial regulatory reforms, domestic security market reforms, occasional capital controls, or the accumulation of financial reserves. Although the G20 was formed in 1999, it did not begin to take center stage in global economic governance until the global financial crisis that started in 2008. Since 2008, systemically important states — both established and aspiring powers — have taken the further steps of committing to increased global financial governance and becoming more integrated into the G20. -

China in the G20: a Narrow Corridor for [email protected] Sino–European Cooperation

Focus | ASIA Dr. des. Sebastian Biba Sebastian Biba and Heike Holbig Goethe University Frankfurt China in the G20: A Narrow Corridor for [email protected] Sino–European Cooperation GIGA Focus | Asia | Number 2 | May 2017 | ISSN 1862-359X Prof. Dr. Heike Holbig Since it hosted the G20 summit and since Trump’s ascent to the US presi- Senior Research Fellow [email protected] dency, China has promoted its role as a defender of free trade. In line with European interests, China has also become a supporter of G20 attempts to GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies tackle the emerging crisis of globalisation. Indeed, China has many reasons Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien to be a facilitative player in the G20. However, its engagement entails limi- Neuer Jungfernstieg 21 tations for the G20 going forward. 20354 Hamburg www.giga-hamburg.de/giga-focus • Compared to India, another emerging power, China has assumed an active role in the G20, seeking to put its stamp on the G20 agenda and calling for the fo- rum’s transformation from a crisis-response mechanism to one of long-term economic governance. • There are various incentives for China to play this role: the G20’s small but widen ed membership relative to the G7, the opportunities for status enhance- ment and for pushing global governance reforms, the loose institutional design, and the focus on issues that China feels comfortable dealing with. • However, China’s prospective engagement has limits. We cannot expect China to agree to a widening of the agenda beyond financial and economic issues. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc. -

Studia Diplomatica Lxviii-3 (2017) the Future of the Gx

stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 1 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM STUDIA DIPLOMATICA LXVIII-3 (2017) THE FUTURE OF THE GX SYSTEM AND GLOBAL GOVERNANCE Edited by Peter DEBAERE, Dries LESAGE & Jan WOUTERS Royal Institute for International Relations stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 2 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM Studia Diplomatica – The Brussels Journal of International Relations has been published since 1948 by Egmont – Royal Institute for International Relations. President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc OTTE Editor in Chief: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations Address FPS Foreign Affairs, Rue des Petits Carmes 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone +32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax +32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website www.egmontinstitute.be Subscription: € 85 (Belgium) € 100 (Europe) € 130 (worldwide) Lay-out: punctilio.be Cover: Kris Demey ISSN: 0770-2965 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 1 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM Table of Contents 3 The Future of the Gx System and Global Governance: An Introduction Peter Debaere, Dries Lesage & Jan Wouters 7 Governing Together: The Gx Future John Kirton 29 Russia and the Future of the Gx system Victoria V. Panova 45 The Gx Contribution to Multilateral Governance: Balancing Efficiency and -

Development Ideas

Development Ideas A study in comparative capitalism Diane Colman A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of New South Wales March 2015 Abstract This thesis compares the meaning and practice of capitalist development in its two very distinct forms – manufacturing and agrarian doctrines. The comparison relies upon a particular understanding of the original idea of development which unites the spontaneous development of capitalism with intentional development strategies and emphasises two distinct frameworks, or doctrines, that development policy has taken. Both doctrines are ‘western’ in their origin, emerging from the nineteenth century industrial revolution, and both have sought to deal with circumstances in which unemployment and a resultant social disorder threaten the further development of capitalism. At this time, a manufacturing doctrine was embraced by state policy makers whose intention was to transform the negative impacts of the spontaneous process of competition through further industrialisation in general. Similarly, when changes occur in the international production of agriculture, the effects on society can be severe. Unemployment in towns and in rural areas forced state officials to construct programs for re-attaching the unemployed to vacant or under-utilised landholdings. This form of development concerns a state policy of agrarian development. The ideas and practices of development in South Korea, as an exemplar of a manufacturing doctrine of development will be compared with those of Papua New Guinea which, during the late colonial period at least, was affected by an agrarian development doctrine. The intentional development paradigm of the developmental state thesis has as its centrepiece the combined mobilisation of both public and private capacity to meet well- defined, long-term, national development goals.