On the Law in General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Calvinism: B

Introduction A. Special Terminology I. The Persons Understanding Calvinism: B. Distinctive Traits A. John Calvin 1. Governance Formative Years in France: 1509-1533 An Overview Study 2. Doctrine Ministry Years in Switzerland: 1533-1564 by 3. Worship and Sacraments Calvin’s Legacy III. Psycology and Sociology of the Movement Lorin L Cranford IV. Biblical Assessment B. Influencial Interpreters of Calvin Publication of C&L Publications. II. The Ideology All rights reserved. © Conclusion INTRODUCTION1 Understanding the movement and the ideology la- belled Calvinism is a rather challenging topic. But none- theless it is an important topic to tackle. As important as any part of such an endeavour is deciding on a “plan of attack” in getting into the topic. The movement covered by this label “Calvinism” has spread out its tentacles all over the place and in many different, sometimes in conflicting directions. The logical starting place is with the person whose name has been attached to the label, although I’m quite sure he would be most uncomfortable with most of the content bearing his name.2 After exploring the history of John Calvin, we will take a look at a few of the more influential interpreters of Calvin over the subsequent centuries into the present day. This will open the door to attempt to explain the ideology of Calvinism with some of the distinctive terms and concepts associated exclusively with it. I. The Persons From the digging into the history of Calvinism, I have discovered one clear fact: Calvinism is a religious thinking in the 1500s of Switzerland when he lived and movement that goes well beyond John Calvin, in some worked. -

Girolamo Zanchi on Union with Christ and the Final Judgment

Perichoresis Volume 18.1 (2020): 41–56 DOI: 10.2478/perc-2020-0003 GIROLAMO ZANCHI ON UNION WITH CHRIST AND THE FINAL JUDGMENT J.V. FESKO* Reformed Theological Seminary ABSTRACT. Union with Christ was a key doctrine for second-generation Reformed theologian Girolamo Zanchi. As a Thomist, Zanchi shared similar elements with Thomas Aquinas in his understanding of salvation as participatio, but his understanding of union with Christ differed with regard to the difference between infused and imputed righteousness. Unlike Aquinas’s doctrine of infused righteousness, Zanchi argued for imputed righteousness, which was both the foundation for one’s justification in this life as well as appearing before the divine bar at the final judgment. Zanchi’s doctrine of union with Christ has the utmost significance for personal eschatology and the judgment believers undergo at the great assize, insights that are worth retrieving for a clear understanding of the relationship between justification and the final judgement. KEYWORDS: Union with Christ, participation (participatio), insitio Christi, imputed righteous- ness, infused righteousness, Aquinas, Zanchi, final judgment Introduction The doctrine of participatio or union with Christ has been a prominent theme in historical and doctrinal literature. Some have claimed that union with Christ is a panacea for healing the doctrinal rift between the Western and Eastern churches (Braaten and Jenson 1998: vii-ix). Others have claimed that union is the great insight of John Calvin (1509-64) and that later Reformed theologians ignored or abandoned his doctrine (Partee 2008: 13-35). Calvin’s successors traded their doctrinal inheritance for a bowl of scholastic lentils when they supposedly moved away from union and embraced the ordo salutis (Evans 2008: 40, 264-67). -

Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology

Stefan Lindholm, Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525551042 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647551043 Stefan Lindholm, Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology Reformed Historical Theology Edited by Herman J. Selderhuis in Co-operation with Emidio Campi, Irene Dingel, Elsie Anne McKee, RichardMuller,Risto Saarinen, and Carl Trueman Volume 37 © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525551042 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647551043 Stefan Lindholm, Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology Stefan Lindholm Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525551042 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647551043 Stefan Lindholm, Jerome Zanchi (1516–90) and the Analysis of Reformed Scholastic Christology Bibliographic informationpublishedbythe Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliotheklists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online:http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISSN 2198-8226 ISBN 978-3-525-55104-2 Yo ucan find alternative editions of this book and additionalmaterial on ourWebsite:www.v-r.de 2016, Vandenhoeck & RuprechtGmbH & Co.KG, Theaterstraße13, D-37073 Göttingen/ Vandenhoeck & RuprechtLLC,Bristol, CT,U.S.A. www.v-r.de All rightsreserved. No partofthis work maybereproduced or utilized in anyform or by anymeans, electronicormechanical, including photocopying, recording,orany information storage and retrieval system, withoutprior written permissionfrom the publisher. Printed in Germany. Typesetting by Konrad Triltsch GmbH, Ochsenfurt Printed and bound by Hubert & Co GmbH & Co.KG, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, D-37079 Göttingen Printed on aging-resistantpaper. -

Heinrich Bullinger, Political Covenantalism and Vermigli's

Heinrich Bullinger, political covenantalism and Vermigli’s commentary on Judges Andries Raath Department of Constitutional Law and Philosophy of Law University of the Free State BLOEMFONTEIN E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Heinrich Bullinger, political covenantalism and Vermigli’s commentary on Judges The Zurich political federalists under the leadership of Heinrich Bullinger had a number of important views in common: firstly, they subscribed to the ideal of the covenanted nation under God; secondly, they maintained the view that magistrates and their subjects have a covenantal calling to live according to God’s law; thirdly, the binding together (consolidation) of the covenanted Christian polity by means of the oath; fourthly, the right to resistance when the conditions of the covenant are broken; fifthly, the offices of magistrates and pastors are mutually to assist one another in maintaining and furthering the conditions and requirements of the Biblical covenant in the consolidated Christian community. Vermigli used these principles, together with the Chrysostomian and Lutheran views on magisterial office, to develop an influential theory of theologico-political federalism in the Reformational tradition. Opsomming Heinrich Bullinger, politieke verbondsluiting en Vermigli se kommentaar op die boek Rigters Die politieke federaliste onder die leierskap van Heinrich Bullinger het ’n aantal belangrike gesigspunte in gemeen gehad: eerstens het hulle die ideaal van die nasie as ’n saamgebinde verbondseenheid onderskryf; tweedens -

Generational Conºict in the Late Reformation

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxxii:2 (Autumn, 2001), 217–242. GENERATIONAL CONFLICT IN THE REFORMATION Amy Nelson Burnett Generational Conºict in the Late Reformation: The Basel Paroxysm Since the tumultuous 1960s, social scientists have been fascinated by the theme of generational conºict. Building on the theoretical structure ªrst proposed by Mannheim in the 1920s, developmental and social psychologists and sociologists have examined a wide range of questions related to generational change, youth movements, and life-cycle course. Historians, too, have applied Mannheim’s insights to the past, fol- lowing the example of Mannheim himself, who explained the nineteenth-century struggle between conservative and liberal val- ues in Germany in terms of generational identity.1 The application of generational theory to history is not with- out its critics, but even those who have expressed reservations about the methodology still acknowledge that Mannheim’s con- cept of social generations provides a useful analytical tool for un- derstanding historical change. The concentration, particularly during the late 1960s and early 1970s, on youth movements and the generation gap has meant that generational analysis has focused on modern history and the fairly recent past. The twentieth cen- tury, in particular, seems tailor-made for generational analysis, given the number and frequency of major life-shaping events, moving from ªn-de-siècle Europe through World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War, and culmi- nating in the student protests of the Vietnam era, which some Amy Nelson Burnett is Associate Professor of History, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. She is the author of “Basel’s Rural Pastors as Mediators of Confessional and Social Discipline,” Central European History, XXXIII (2000), 67–86; “Melanchthon’s Reception in Basel,” in Karen Maag (ed.), Melanchthon in Europe: His Workand Inºuence Beyond Wittenberg (Grand Rapids, 1999), 69–85. -

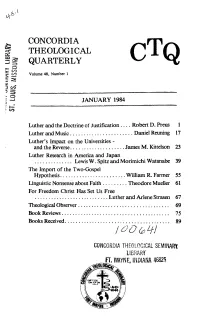

Luther's Impact on the Universities--And the Reverse

CONCORDIA B Qznr THEOLOGICAL 00- J3 QUARTERLY Volume 48, Number 1 JANUARY 1984 Luther and the Doctrine of ~ustification. Robert D. Preus Luther and Music. Daniel Reuning Luther's Impact on the Universities - and the Reverse. James M. Kittelson Luther Research in America and Japan . Lewis W. Spitz and Morimichi Watanabe The Import of the Two-Gospel Hypothesis. William R. Farmer Linguistic Nonsense about Faith . Theodore Mueller For Freedom Christ Has Set Us Free . Luther and Arlene Strasen Theological Observer . Books Received. CONCORDIA THEOLOC~CALSEMINAR1 L16WRY Luther's Impact on the Universities -and the Reverse James M. Kittelson Few topics could be more appropriate to observations during this year of the Luther jubilee than Luther's impact upon universities and their influence upon him and his movement. A religious man, he was also a university man who both developed his understanding of the Gospel while performing his duties as a professor and who, when faced with a practice he considered outrageous, condemned it first in the standard university way of doing business and only then appealed to a wider public au- dience outside the academy. On the other hand, few topics have been accorded such lack of attention as this one, and perhaps with good reason. The dramatic events of the Reformation, or at least most of them, took place outside universities. The Heidelberg Disputation oc- curred at a meeting of the Augustinians; Worms was an Im- perial Diet; the Augsburg Confession was written for another Imperial Diet. Luther's most influential works, the German Bi- ble and the catechisms, were indeed produced by a university professors but they were intended for a decidedly non-universi- ty audience. -

Petrus Martyr Vermigli (1499-1562)

Petrus Martyr Vermigli (1499-1562) Europäische Wirkungsfelder eines italienischen Reformators1 von EMIDIO CAMPI In den zur Zeit ruhigen Gewässern der Reformationsforschung scheint der 500. Geburtstag von Petrus Martyr Vermigli kleine, aber feine Wellen zu schla gen. Zumindest gibt es Anzeichen dafür, daß neuerdings wieder ein wissen schaftlicher Diskurs über diese wenig bekannte Schlüsselfigur des reformier ten Protestantismus und der europäischen Geistesgeschichte des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts in Gang gekommen ist. So haben planende Voraussicht und glücklicher Zufall Hand in Hand dafür gesorgt, daß die Jahresversammlung des ehrwürdigen Zwinglivereins im Juni 1999 ihre Aufmerksamkeit auf den italienischen Glaubensflüchtling richtete. Anfang Juli fand unter großer inter nationaler Beteiligung ein Symposium in Kappel am Albis2 statt, das die Wir kung und Bedeutung seiner Tätigkeit in Zürich würdigte. Im September wurde während der Jahreskonferenz des Sixteenth Century Journal in St. Louis, Mis souri, ein fachübergreifendes Vermigli-Kolloquium durchgeführt.3 Im Okto ber folgte schließlich eine Zusammenkunft an der Universität Padua4, der alma mater Vermiglis, bei der die Ergebnisse dieser konzentrisch angelegten Tagun gen gezielt weitergeführt wurden. Erfreulich ist zudem der Umstand, daß das Jahr 1999 nicht nur Vermigli-Kongresse brachte, sondern auch eine beträcht liche Anzahl neuer Editionen5, Studien6 und Dissertationsprojekte7 verzeich nen konnte. 1 Vortrag, gehalten an der ordentlichen Mitgliederversammlung des Zwinglivereins vom 16. Juni 1999 in der Helferei Großmünster. Für die Drucklegung wurde er geringfügig überar beitet und mit den Anmerkungen versehen. Für ihre wertvolle Mithilfe bei der Fertigstellung des Aufsatzes danke ich Frau Alexandra Seger und Herrn Michael Baumann. 1 Petrus Martyr Vermigli in Zürich (1556-1562). Humanismus, Republikanismus, Reforma tion. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Debated Issues in Sovereign Predestination: Early Lutheran Predestination, Calvinian Reprobation, and Variations in Genevan Lapsarianism. By Joel R. Beeke. Reformed Historical Theology 42. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017, 252 pp., 65,00 €. Joel Beeke sets out to trace the doctrine of double predestination in six- teenth-century Lutheranism and in John Calvin and his successors in Geneva through the eighteenth century. He also contributes to the scholarly debates surrounding these issues. In part 1, Beeke states, “by way of analyzing Article 11 of the Formula of Concord in its historical/doctrinal germination, formulation, comparison, and reception, I hope to show that its role in historical theology’s development of a scriptural doctrine of predestination is by no means negligible as com- monly assumed” (16). The germination took place with Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon. While Luther affirmed double predestination, some of his theological distinctions, and especially his emphasis on consolation, sowed the seeds of later confessional single predestination. Beeke defends Melanchthon against charges of synergism, but notes his refusal to separate reprobation from foreknowledge does open his teaching up for misunder- standing. A distinctly Lutheran formulation of predestination emerged in the controversy between Johann Marbach and Jerome Zanchi in Strasbourg and was codified in the Formula of Concord. For confessional Lutherans, predestination is singular, election is the historical outworking of salvation, and the doctrine can only be considered in Christ for the comfort of God’s people. Thus, there is no place for reprobation. Beeke contrasts this with the Canons of Dordt and then shows that “Lutheran history confirms that monergistic, single predestination is neither a biblical or rational solution; repressed reprobation must end in repressed election” (74). -

Lutheran Synod Quarterly

LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 52 • NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2012 The theological journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord FACULTY............. Adolph L. Harstad, Thomas A. Kuster, Dennis W. Marzolf, Gaylin R. Schmeling, Michael K. Smith, Erling T. Teigen The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Contents Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the LSQ Vol. 52, No. 4 (December 2012) Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. ARTICLES The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a Perspicuity: The Clarity of Scripture ..............................................267 combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year Shawn D. Stafford for domestic subscriptions and $35.00 U.S. per year for international subscriptions. The Formula of Concord in Light of the Overwhelming All subscriptions and editorial correspondence should be sent to the following Arminianism of American Christianity ..........................................301 address: Timothy R. Schmeling Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary The Divine Liturgy and its Use .....................................................335 Attn: Lutheran Synod Quarterly Gaylin R. -

Immortality and Method in Ursinus' Theological Ambiance John Donnelly Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-1986 Immortality and Method in Ursinus' Theological Ambiance John Donnelly Marquette University, [email protected] Post-print. "Immortality and Method in Ursinus's Theological Ambiance," in Controversy and Conciliation: The Reformation and the Palatinate 1559-1583. Ed. Derk Visser. Allison Park, PA: Pickwick Publications, 1986: 183-195. © 1986 Wipf and Stock Publisher. Used with permission. Immortality and Method in Ursinus's Theological Ambiance John Patrick Donnelly, S. J. The main theological and religious positions of mainstream Pro testantism in Europe and America were staked out by the first genera tion of Martin Luther and the second generation of John Calvin. Most reformation research has rightly concentrated on the first two genera tions, but recently American scholarship has started to examine the role of the third generation represented by Zacharias Ursinus and his con temporaries, the Shapers of Religious Traditions. This conference brings together many of the scholars who have contributed to that thrust-I was tempted to say younger scholars, but as I look around I n()te that most of us have acquired gray hair in the decade since we started publishing in this area. It has always seemed to me that a major contribution of the third generation of reformers was their shift of theological method away from the strongly biblical theologies of Luther and Calvin toward the neoscholasticism of the Age of Protestant Orthodoxy, a period which stretched from the late sixteenth century well into the eighteenth cen tury, and in places remained important even in the nineteenth century, for instance the Calvinism of the American Princeton School. -

Peter Martyr Vermigli and Thomas Aquinas on Predestination

CONFLUENCE AND INFLUENCE: PETER MARTYR VERMIGLI AND THOMAS AQUINAS ON PREDESTINATION Frank A. James III Introduction In his Paradiso, Dante Alighieri describes predestination as a mystery whose “root lies hidden from the intellect.”1 By its very inscrutability, the idea of predestination has fascinated theologians from Augustine to Pannenberg.2 It also has been a central dogma, as it were, for Richard A. Muller’s ground-breaking research. When he published his doctoral dis- sertation over twenty-five years ago, Christ and the Decree, few could have anticipated that his approach to the development of post-Reformational theology would have lasting value. His was after all a rather obscure area of research, which hitherto had been largely the domain of dead-white- European-males with hard to pronounce names. From the outset of his career, Muller recognized the historiographical significance of Peter Martyr Vermigli and the doctrine of predestination. In Christ and the Decree, Muller made what many considered a rather star- tling academic judgment: We must divide the laurels between Calvin and Vermigli in judging the influence of their respective doctrines of predestination. Whereas Calvin’s basic structure and definition, which designates election and reprobation as almost coordinate halves of the decree, had more impact…[it was Vermigli’s conception of predestination that] would eventually be enunciated as the confessional norm of Reformed theology.3 1 Divine Comedy, Paradisio, Canto XX: “O Predestination! How remote and dim, Thy root lies hidden from the intellect which only glimpses the First Cause Supreme! And you, ye mortals, keep your judgment checked, since we, who see God, have not therefore skill To know yet all the number of the elect, And such defective sight is sweet for us, Because our good is refined by this good, That which God wills we also will.” 2 Wolfhart Pannenberg’s dissertation: Die prädestinationslehre des Duns Skotus in Zusammenhang der scholastischen Lehrntwicklung (Göttingen: V&R, 1954). -

Jerome Zanchi, the Application of Theology, PATRICK J

Jerome Zanchi, the Application of Theology, PATRICK J. and the Rise of the English O’BANION Practical Divinity Tradition* Cet article s’inscrit dans le débat récemment relancé sur la relation entre les théologiens scolastiques de la Réforme et les premiers réformateurs, mais propose également de l’amener dans une nouvelle direction. On y ana- lyse d’abord la doctrine de Dieu, telle que développée par Jerome Zanchi (1516–1590), en mettant en relief comment il passe de conclusions de théo- logie systématique à des implications de théologie pratique, en particulier, à travers son usage de la convention dite de l’usus doctrinae. L’article cherche ensuite à estimer l’impact de cette convention en dehors des milieux érudits en explorant la relation entre le discours de Zanchi et la tradition anglaise pratique de la divinité. On y met donc en lumière comment les pasteurs et les théologiens populaires ont emprunté à Zanchi dans le cadre de leur charge d’âmes et de réforme de la nation anglaise. wo early modern likenesses of the Italian exile and Reformed theolo- Tgian Jerome Zanchi (1516–1590) exist.1 The first, the work of Hendrik Hondius, was published in his Icones virorum nostra patrumque memoria illustrium (1599). The second, probably engraved by Theodore de Bry, was included in Jean-Jacques Boissard’s Bibliotheca chalcographica (1669). Beneath each engraving, the artists added a few lines of Latin verse celebrat- ing Zanchi’s life. Although there are differences between the verses in the two works, both agree that Zanchi was nulli pietate secundus: second to none in piety.