THE VANGUARD JAZZ ORCHESTRA New World Records 80534

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Rudy? Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents ready rudy? Arranged by duke pearson transcribed and Prepared by Dylan Canterbury full score jlp-7333 Music by Duke Pearson Copyright © 1965 Gailancy Music International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2015 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Duke Pearson. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke pearson series ready rudy? (1966) Background: Duke Pearson was an important pianist, composer, arranger and producer during the 1960s and 1970s. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1932 and played trumpet as well as piano with many local groups. After attending Clark College, he toured with Tab Smith and Little Willie John before he moved to New York City in January of 1959. Donald Byrd heard him, and Byrd was the leader of Pearson’s first recording session. Soon Pearson was playing with the Benny Golson-Art Farmer Jazztet. Pearson became the musical director for Nancy Wilson, as well as continuing to tour and record with Donald Byrd. In 1963, Blue Note Records producer and musical director Ike Quebec passed away, and Pearson became Blue Note’s A&R director, as well as make his own albums. Grant Green, Stanley Turrentine, Johnny Coles, Blue Mitchell, Hank Mobley, Bobby Hutcherson, Lee Morgan and Lou Donaldson all benefited from his arranging and producing skills. Albums that Pearson recorded under his own name ranged in instrumentation from trios to quintets, sextets and octets to choral ensembles. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thad Jones & Mel Lewis: Live at the Village Vanguard] Down Beat 35:8 (April 18, 1968)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5438/morgenstern-dan-record-review-thad-jones-mel-lewis-live-at-the-village-vanguard-down-beat-35-8-april-18-1968-225438.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thad Jones & Mel Lewis: Live at the Village Vanguard] Down Beat 35:8 (April 18, 1968)

Records are reviewed by Don DeMicheal, Gilbert M. Erskine, Kenny Dorha m, Barbara Gardner, Bill Mathieu, Marian McPartland, Dan Mor 11e nslar Bill Quinn, Harvey Pekar, William Russo, Harvey Siders, Pete Welding, John S. Wilson, and Michael Zwerin. Reviews are signed by !lie Wr't n, I ers Ratings are : * * * * * excellent, * * * * very good, * * * good, * * fair, * poor . ' When two catalog numbers are listed, the first is mono, and the second is stereo . times (especially on Yellow Days) · his Thad Jones-Mel Lewis •- •- -. ... touch is uncannily close to the master 's. LIVE AT THE Vl.LLAGB VANGUA.ll." Solid S1A1e SS l80l6: L/lflc Pi:<lo ll; ,1 "/l'v..,. BIG BANDS Two ringers were brought in to beef up l'reodom; Barba l'eo/i11'; Do11'1 Git Sn1ty• tltl•, /0111 Tree; Samba Co11 Gde/m. ' "' 1I. Duke Ellington the trumpet section, currently the ban.d's weakest link. Everybody was on best be Personnel: Jone1, flu·cgelhoro; Snooky y 0 SOUL CALL-Verve V/V6·870l: La Pim Bell• Jimmy No1tingb3m, Marvin Stamm, Rkfiard ~•• Af.-i&11l11r;IVett litdia11 Pa11caltt; Soul C111/;Slti11 Jiavior, it seems-the band sounds tight Iiams, Bill Berry. trumpets; Bob Brool<o, II, Du/I; Jan, Will, Sm11. and together at all times. The superb ·re Garnett Bl'owo, Tom Mclmo,h, Cliff fi~a~yer, Personnel: Cnt Anderson, Herbie Jones, Cootie irombones; Jerome Richnrdson, Jerry Dad !>tr, \Villla 'ms. M,rccer I!llingron. uumpors; Buster cord ing brings out the foll flavor of the Joe Parcell, '.Eddie Daniels, -Pepper Adams r~t• lloiaod Hannn piano; Sam Herm an, • IM • Cooper, Lawrence Brown, Chuck Connors , rrom• magnificent Ellington sound; the reeds, in 1 bonci.: Russell Procope. -

Thad Jones Discography Copy

Thad Jones Discography Compiled by David Demsey 2012-15 Recordings released during Thad Jones’ lifetime, as performer, bandleader, composer/arranger; subsequent CD releases are listed where applicable. Each entry lists Thad Jones compositions/arrangements contained on that recording. Album titles preceded by (•) are contained in the Thad Jones Archive collection. I. As a Leader or Co-Leader Big Band Leader or Co-Leader (chronological): • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Live at the Vanguard (rec. 1/7 [sic], 3/21/66) [live recording donated by George Klabin] Contains: All My Yesterdays (2 versions), Backbone, Big Dipper (2 versions), Mean What You Say, Morning Reverend, Little Pixie, Willow Weep for Me (Brookmeyer), Once Around, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Low Down, Lover Man, Don’t Ever Leave Me, A-That’s Freedom • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, On Tour (rec. varsious dates and locations in Europe) Discs 1-7, 10-11 [see Special Recordings section below] On iTunes. • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, In the Netherlands (rec. 1974) [unreleased live recording donated by John Mosca] • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Presenting the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra (rec. 5/4-5-6/66) Solid State UAL18003 Contains: Balanced Scales = Justice, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Mean What You Say, Once Around, Three and One • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Opening Night (rec. 1[sic]/7/66, incorrect date; released 1990s) Alan Grant / BMG Ct. # 74321519392 Contains: Big Dipper, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Once Around, All My Yesterdays, Morning Reverend, Low Down, Lover Man, Mean What You Say, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Willow Weep for Me (arr. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Western Invitational Jazz Festival 2013–14 Season Saturday 15 March 2014 484Th–486Th Concerts Dorothy U

34th Annual Western Invitational Jazz Festival 2013–14 Season Saturday 15 March 2014 484th–486th Concerts Dorothy U. Dalton Center BILLY DREWES, Saxophone, Guest Artist SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Big Bands Combos 8:00 Kalamazoo Central High School 8:20 Byron Center High School Jazz Lab 8:40 West Michigan Home School 8:40 Loy Norrix High School 9:00 Mishawaka High School 9:00 Black River – “Truth” 9:20 Reeths-Puffer High School 9:20 Byron Center I 9:40 Grandwille High School 9:40 West Michigan Home School 10:00 WMU Jazz Lab Band 10:00 Northview 10:30 Byron Center High School Jazz Band 10:30 Community 5 10:50 Black River High School 10:50 Community 4 11:10 Ripon High School 11:10 Grandville 11:30 Comstock Park High School 11:30 Northside 11:50 Mona Shores High School BREAK 12:40 Mona Shores 1:00 Stevenson High School 1:00 Byron Center II 1:20 Northside High School 1:20 Community 3 1:40 East Kentwood High School 1:40 Community 2 2:00 Lincholn Way High School 2:00 Waterford Kettering 2:20 Northview High School 2:20 Stevenson 2:40 Byron Center Jazz Orchestra 2:40 Community 1 3:15 WMU Advanced Jazz Combo (Rehearsal B) 4:00 Clinic with guest artist Billy Drewes and the Western Jazz Quartet (Recital Hall) 5:00 Announcement of Outstanding Band and Combo Awards and Individual Citations BREAK 7:30 Evening Concert featuring an Outstanding Band and Combo from the Festival and Billy Drewes with the WMU Jazz Orchestra If the fire alarm sounds, please exit the building immediately. -

Ron Mcclure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar

NEW YORK FebruaryVANGUARD 2010 | No. 94 Your FREE Monthly JAZZ Guide to the New ORCHESTRA York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com a band in the vanguard Ron McClure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar NEW YORK We have settled quite nicely into that post-new-year, post-new-decade, post- winter-jazz-festival frenzy hibernation that comes so easily during a cold New York City winter. It’s easy to stay home, waiting for spring and baseball and New York@Night promising to go out once it gets warm. 4 But now is not the time for complacency. There are countless musicians in our fair city that need your support, especially when lethargy seems so appealing. To Interview: Ron McClure quote our Megaphone this month, written by pianist Steve Colson, music is meant 6 by Donald Elfman to help people “reclaim their intellectual and emotional lives.” And that is not hard to do in a city like New York, which even in the dead of winter, gives jazz Artist Feature: Harris Eisenstadt lovers so many choices. Where else can you stroll into the Village Vanguard 7 by Clifford Allen (Happy 75th Anniversary!) every Monday and hear a band with as much history as the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra (On the Cover). Or see as well-traveled a bassist as On The Cover: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Ron McClure (Interview) take part in the reunion of the legendary Lookout Farm 9 by George Kanzler quartet at Birdland? How about supporting those young, vibrant artists like Encore: Lest We Forget: drummer Harris Eisenstadt (Artist Feature) whose bands and music keep jazz relevant and exciting? 10 Svend Asmussen Joe Maneri In addition to the above, this month includes a Lest We Forget on the late by Ken Dryden by Clifford Allen saxophonist Joe Maneri, honored this month with a tribute concert at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn. -

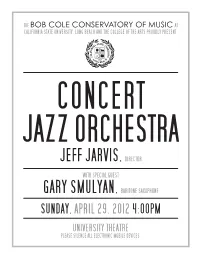

Jeff Jarvis,Director

CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR WITH SPECIAL GUEST GARY SMULYAN, BARITONE SAXOPHONE SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2012 4:00PM UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM GENTLY / Bob Mintzer This well-crafted original is the title track of a recording of the Bob Mintzer Big Band. This recording project was unique in that the horn section stood in a circle surrounding a specially designed ribbon microphone that was extremely sensitive and accurate. This microphone would not accept loud dynamic levels, so Bob Mintzer wrote material that showcased the band playing at softer dynamics, which resulted in frequent use of muted brass, flugelhorns, and woodwinds. Today’s soloists include Josh Andree (tenor sax) and Will Brahm (guitar). THEN AND NOW / George Stone This terrific original composition and arrangement is featured on a recent recording of the George Stone Big Band entitled “The Real Deal”, performed by a collection of Southern California’s finest studio musicians. George’s music is frequently featured at our concerts because of its superior quality, both from a compositional standpoint and also in terms of orchestration. This piece has it all—melodic integrity, intense rhythms, lush harmonies, and sufficient solo space. Today’s soloists include Eun young Koh (piano), Josh Andree (tenor sax), Will Brahm (guitar), and Daniel Hutton (alto sax). CHINA BLUE / Jeff Jarvis Originally composed as a commission for a big band in Williamsburg VA, the work features a winding trumpet melody supported by muted trombone parts, warm flugelhorn lines, and beautiful woodwind parts played by the saxophone section. The piece proves challenging since the musicians are faced with executing exposed parts with delicacy and restraint. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Cpfj 2014 Spring Concert Series Sunday March 16 5

Connecting Jazz Lovers CPFJ Newsletter JANUARY/FEBRUARY with Each Other 2014 & the Music! Issue #20 CPFJ 2014 SPRING CONCERT SERIES SUNDAY MARCH 16 5 P.M. SHERATON HARRISBURG HERSHEY . JOEY DEFRANCESCO TRIO PAUL BOLLENBACK(G) CARMEN INTORRE (DR) SUNDAY APRIL 6 7 P.M. POLLOCK CENTER FOR THE ARTS, CAMP HILL . CECILE McLORIN SALVANT , SUNDAY MAY 25 WITF PUBLIC MEDIA CENTER . EHUD ASHERIE & This series is underwritten by a generous contribution from the Shearer Family Fund KEN PEPLOSKI of the Foundation for Enhancing Communities on behalf of R. Scott Shearer LOOK. INSIDE THE VIBE! Exec. Dir. Letter - pg.2 Jazz Passings 2013 - pg. 10 &11 Grants & Donors - pg. 3 New Scholarship & Spring Concert Series - pg. 4 & 5 Ticket order form - pg.12 Area Clubs & Concerts - 6 & 7 Phil Woods/Dave Stahl - pg. 13/14 Jazz Camp & Youth Band - pg. 8 Membership Application - pg. 15 Dauphin Co. Grant - pg. 9 CPFJ Jam Sessions - pg. 16 1 The Vibe is published monthly at the Central PA Friends of Jazz, 5721 Jonestown Road, Harrisburg PA 17112 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S REPORT: Central Pennsylvania Friends of Jazz HAPPY NEW YEAR! Thanks to all for your support in 2013. We had a very successful year with great concerts: the Cyrus Chestnut tribute to Dave Brubeck, violinist Christian Howes, legendary 5721 Jonestown Road vocalist Freddy Cole, the Kenton Alumni Big Band, drummer Clarence Penn’s Monk tribute, and Harrisburg PA 17112 dynamic pianist Anthony Wonsey; our best Jazz Camp ever with a great faculty and 70 students; TEL: 717-540-1010 membership in CPFJ reached 600 - a level not seen for over 15 years; WEB: We have been awarded a generous grant from the Dauphin County Commissioners that will enable www.friendsofjazz.org us to present a concert on September 5th at Fort Hunter Park as part of the Dauphin County Jazz EMAIL: & Wine Festival.