Sympathetic Symbols, Social Movements, and School Desegregation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Desegregation and the Law — Brown and Black Victories During the Civil Rights Era

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2014 Volume III: Race and American Law, 1850-Present Hidden Realities: School Desegregation and the Law — Brown and Black Victories During the Civil Rights Era Curriculum Unit 14.03.05 by Waltrina D. Kirkland-Mullins Between mid-November through the first week in January, teachers at the Davis Street Arts & Academics Interdistrict Magnet School in New Haven, CT prepare for our annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Assembly. We collectively lay the foundation for examining the Civil Rights era and its impact on American society as we know it today. Grades Pre-K through 1 take a simplistic, developmentally appropriate look at the civil rights movement with emphasis on embracing cultural similarities and diverse peoples working and living together as a united community. Grades 2 through 3 take a generic look at Rosa Parks and the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycotts. Grades 4 through 6 briefly examine past injustices experienced by African Americans in the segregated South, including examining the story of 14-year old Emmet Till. Each of these grade levels delves into an excerpted overview of Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, accompanied by mosaic images of myriad people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial. Emphasis is placed on Black/White relationships and individuals who fought against racial injustice during the era. Although teacher and student efforts regarding the aforementioned prove laudable, the effort is in a sense insufficient. For years, we have taught our children about the black/white inequities encountered in the struggle for civil rights. -

Almost 10 Years Before Brown Vs. Board of Education, Sylvia Mendez

Towner Award Nominee Books for 2016 Curriculum Connections: Civil Rights, Segregation, Author and Illustrator: Duncan Tonatiuh Discrimination, Integration, Equality in Education, Brown vs. Board of Education, Mexican Americans, American History, Heritage New York: Abrams Books for Young Excellent for close reading, review of book features, and Readers, 2014 building band 3-5 complex vocabulary, as well as 40 Pages persuasive writing activities. AR Level: 5.1 Lexile: 870 Available as a DVD for read-along activities. Almost 10 years before Brown vs. Board CCSS for Primary Grades CCSS for Intermediate Grades . RI.2.2 Identify the main topic of a . RI.3.9 Compare and contrast the of Education, Sylvia Mendez and her multi-paragraph text as well as the most important points and key parents helped end school segregation focus of specific paragraphs within the details presented in two texts on text. the same topic. in California. An American citizen of . RI.2.3 Describe the connection . RI.4.3 Explain events, Mexican and Puerto Rican heritage who between a series of historical events . procedures, ideas, or concepts in spoke and wrote perfect English, . in a text. a historical . , including what Mendez was denied enrollment to a . RI.2.5 Know and use various text happened and why, based on features . to locate key facts or specific information in the text. “Whites only” school. Her parents took information in a text efficiently. RI.5.2 Determine two or more action by organizing the Hispanic . RI.2.6 Identify the main purpose of a main ideas of a text and explain community and filing a successful text, including what the author wants to how they are supported by key answer, explain, or describe. -

Scope Dec/Jan 2017-18+

Drama DRAMATIZATION a story based on true events The FIGHT for WHAT’SFor some, California in the 1940s was a dream: palm trees, beaches, glamorous movie stars. But for others, it was a RIGHT place of great injustice. Sylvia Mendez (right) and her family helped change that. Page 16: R. Gates/Getty Images (top left); Hulton Archive/Getty Images (top right); Underwood Archives/UIG/REX/Shutterstock (middle); William M. Graham/Hulton Underwood M. Archive/ right); Archives/UIG/REX/Shutterstock William (top Images Archive/Getty (middle); Hulton left); Gates/Getty (top R. Images 16: Page Bettmann/Getty left); right); (top Images (top Photos Freed/Magnum ©Leonard 17: Page Getty right). Vintage (bottom Stock/Corbis Images Getty Kirn via left); (bottom Images Mendez) (Sylvia prohibited. is reproduction or Duplication only. permission with used be to family Mendez the courtesy of Pictures By Spencer Kayden 16 SCHOLASTIC SCOPE • DECEMBER 2017/JANUARY 2018 SCHOLASTIC SCOPE • DECEMBER 2017/JANUARY 2018 17 Secretary: Those two may SEPARATE Characters enroll here, but not the AND UNEQUAL In the 1940s, Mexican- Circle the character you will play. *Indicates large speaking role Mendez children. Americans faced terrible Aunt Sally: Excuse me? prejudice. Many restaurants, *Stage Directors 1 & 2 (SD1, SD2) *Aunt Sally, Sylvia’s aunt Miguel, a classmate SD2: The secretary points at stores, and movie theaters Storytellers 1, 2, & 3 (ST1, ST2, ST3) Secretary *Mr. Marcus, a lawyer displayed signs like this one. Sylvia and Jerome, who have *Sylvia Mendez, an 8-year-old girl *Mama, Sylvia’s mother, Felícitas Mr. Harris, the superintendent Inset: First-grade students at dark skin and dark hair. -

Segregation Sohyun An

Social Studies and the Young Learner 32 (3) pp. 3–8 ©2020 National Council for the Social Studies First Graders’ Inquiry into Multicolored Stories of School (De)Segregation Sohyun An Terrie: Mommy! Guess what I learned today? Terrie: Yes! Like other girls, Mamie had to go to an unfair school because she was not white! Me: Seems like something exciting! Me: Gotcha. By the way, why did you pick Mamie for your Terrie: Yes! Mamie Tape! Look at this. She is like me! Well, Venn diagram? (Fig, 1) she is Chinese, and I am Korean, but she has the same hair and eye color as me. She was brave like me, too! Terrie: Well, I like all the stories, but I like Mamie’s the best She said, “Hey, it’s not fair that I have to go to a seg- because she looks like me! regated school!” I am the mother of Terrie, a Korean American girl in Ms. Amber Me: I see. So Mamie was like Ruby Bridges, Sylvia Mendez, King’s first-grade classroom in a public school in Georgia.1 I am and Alice Piper—the girls you’ve learned about so far also a scholar of social studies education. My hope as a mother- from your teacher? Figure 1. January/February 2020 3 scholar is that all children, including mine, will be excited grade teachers regarding their upcoming unit on Ruby Bridges, to learn about U.S. history because they can see people like one of the historical figures included in the state’s first-grade themselves in the story of their country. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies The Representation of Hispanic masculinity in US cinema 1998-2008: Genre, Stardom and Machismo by Victoria Lynn Kearley Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT The Representation of Hispanic masculinity in US cinema 1998-2008: Genre, Stardom and Machismo Victoria Lynn Kearley This thesis examines how the conventions of four distinct genres, the star personas of two key Hispanic male stars and conceptions of Hispanic men as 'macho' intersected in constructing images of Hispanic masculinity in Hollywood between the years 1998 and 2008. The work makes an original contribution to knowledge as the first extensive study of Hispanic masculinity in contemporary Hollywood and affording new insights into the way in which genre conventions and star personas contributed to these representations. -

Ep. 01 Transcript

Page 1 of 11 TRANSCRIPT Copyright © 2017 Orange County Department of Education. All Rights Reserved. Title: Mendez v. Westminster Sylvia: We would stop at that school everyday and see those kids go in but this playground was right next to the street and in that playground they had monkey bars, they had teeter- totter, they had swings and my thing was that I always wanted to go to that school because of the playground, 'cause we didn't have all that at the other school. Jeff: In 1944, eight year old [Sylvia Mendez 00:00:32] didn't understand why she and her brothers couldn't go to the school with the nice playground. Neither could their parents, [Gonzalo 00:00:39] and [Felicitas Mendez 00:00:39]. What resulted was Mendez versus [Westminster 00:00:42], a landmark court case that shattered many of the legal justification for segregating public schools. Maybe you haven't heard of the Mendez, maybe you're more familiar with the Brown versus the Board of Education decision of 1954, but not only did the Mendez case precede that decision by seven years, it lay the foundation for the United States Supreme Court declaration once and for all that segregated schools were in violation of the constitution. We sat down with Sylvia Mendez and Gonzalo Mendez Junior on the 70th anniversary of the resolution to the Mendez case. Speaker 3: What- [Gregor 00:01:17] are we good on sound? [crosstalk 00:01:19] Gonzalo jr: You can hear us? Speaker 5: Yes, I can hear you. -

La Voz De Austin March 2011.Pmd

Free Gratis Volume 6 Number 3 LaLaLa VVVozozoz A Bilingual Publication March, 2011 www.lavoznewspapers.com (512) 944-4123 Inside this Issue People in the News Hispanic Health and Assimilation Letter to the Editor from Ed Gomez Greater Austin Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Announces New Board Southwest Key Makes Proposal to School District Juan Montoya Comments on Brownsville Native The Day of An Interview the Fallen with Lori Moya En Palabras AISD Trustee Hay Poder in District 6 Page 2 La Voz de Austin - March, 2011 People in the News After seeing her six children Rolando Fernandez Jr. currently 1998 with a B.A. in History and for Mexican American Studies, graduate from college, she became serves as the City of Austin Public Policy, along with a minor in and the Center for African & a writer, penning both poems and Assistant Director of the Contract Film and Media Studies. African American Studies. short stories and volunteered at the and Land Management Mexic-Arte Museum from 1984 to Department. Prior to this, After moving to Austin that same Her recent scholarship has 2010. In 2001, Aurora attended Fernandez served as the Assistant year to pursue film and music, she focused on U.S. Latina/o President George W. Bush First to Austin City Manager Marc Ott returned to one of her first loves - performance and popular culture. State Dinner for President Fox of from August 2008 to October 2010. acting - and was a Vortex Her articles, “Remembering Selena, Mrs. Orozco Passes Mexico with daughter Sylvia. As Assistant to the City Manager, Repertory Company member for Re-membering Latinidad,” (Theatre Away After Long Fernandez provided leadership to three years. -

Mendez Et. Al V. Westminster Et. Alâ•Žs Impact on Social Policy and Mexican-American Community Organization in Mid-Century O

Voces Novae Volume 5 Article 8 2018 Mendez et. al v. Westminster et. al’s Impact on Social Policy and Mexican-American Community Organization in Mid-Century Orange County Jared Wallace Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Wallace, Jared (2018) "Mendez et. al v. Westminster et. al’s Impact on Social Policy and Mexican-American Community Organization in Mid-Century Orange County," Voces Novae: Vol. 5 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol5/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wallace: Mendez et. al v. Westminster et. al’s Impact on Social Policy and Mendez et. al v. Westminister et. al Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 4, No 1 (2013) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 4, No 1 (2013) > Wallace Mendez et. al v. Westminster et. al's Impact on Social Policy and Mexican- American Community Organization in Mid-Century Orange County Jared Wallace In history, singular events often overshadow the long-term movements that follow. Highly publicized or sensationalized events and people that either inspire or disgust readers are usually given the most attention in history books, while the movements that develop afterwards are viewed as less important and often forgotten. Fortunately, there comes a point when scholars recognize a condition within society and choose to look beyond the highlights of history and instead give heed to the lowlights that never reached national praise, but still had a significant impact on the lives of regular citizens over long periods of time. -

The Racial Politics of Chican@ Linguistic Scripts in US Media

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara “Can joo belieb it?”: The Racial Politics of Chican@ Linguistic Scripts in U.S. Media (1925-2014) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chicana and Chicano Studies by Sara Veronica Hinojos Committee in charge: Professor Dolores Inés Casillas, Chair Professor Cristina Venegas Professor Mary Bucholtz Professor Anna Everett June 2016 The dissertation of Sara Veronica Hinojos is approved. _____________________________________________ Cristina Venegas _____________________________________________ Mary Bucholtz _____________________________________________ Anna Everett _____________________________________________ Dolores Inés Casillas, Committee Chair April 2016 “Can joo belieb it?”: The Racial Politics of Chican@ Linguistic Scripts in U.S. Media (1925-2014) Copyright © 2016 by Sara Veronica Hinojos iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was brought to you by the endless support of the Chicano Studies Institute (CSI) at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). They financially assisted in realizing my travels to archives, conferences, and research equipment for my first research project until the last chapter of the dissertation, a special thank you to Carl Gutierrez-Jones, Theresa Peña, Laura Romo, and Raphaëlla Nau. To the Center for Black Studies Research (CBSR) at UCSB for funding my final archival trip, especially to Diane Fujino and Mahsheed Ayoub for all your work. I am grateful for the National Science Foundation (NSF) University of California Diversity Initiative for Graduate Study in the Social Sciences (UC DIGSSS) program that was instrumental in my transition into graduate school, thank you Mary York. Finally, to my home department Chicana and Chicano Studies for believing in my research and work ethic especially for the endless teaching opportunities and block grant funding so I may focus on my writing; specifically, to Katherine Morales, Joann Erving, Sonya Baker, Shariq Hashmi, and Mayra Villanueva. -

Defenderse Del Mundo Con Las Mismas Armas Que El Mundo Usa

Defenderse del mundo con las mismas armas que el mundo usa: Lupe Vélez y Dolores del Río (1921-1946) Maria Paula Orozco Espinel Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Escuela de Estudios de Género Bogotá, Colombia 2019 Defenderse del mundo con las mismas armas que el mundo usa: Lupe Vélez y Dolores del Río (1921-1946) Maria Paula Orozco Espinel Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Magister en Estudios de Género Directora: Gisela Cramer Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Escuela de Estudios de Género Bogotá, Colombia 2019 A Clara y Camila. Agradecimientos Agradezco a mi directora de tesis, la profesora Gisela Cramer, por sus consejos y por su continua disponibilidad a escucharme y leerme. Ella me acompañó en el proceso de seguir mis intereses investigativos más allá de la disciplina histórica, siempre con mucha calidez y empatía. Los encuentros del grupo “Relaciones Internacionales e Historia Transnacional”, los cuales ella ha hecho posibles, me permitieron desarrollar mi investigación en un espacio abierto a la integración y discusión entre personas de pregrado, maestría y doctorado. Este grupo fue fundamental para desarrollar mis reflexiones. Allí mis compañeras y compañeros —sin olvidar a Jorge Enrique Casilimas Quintero (Q.E.P.D.)— escucharon mis avances y dudas en diferentes ocasiones, y me dieron generosas recomendaciones. De la Escuela de Estudios de Género agradezco a la profesora Tania Pérez-Bustos por haberme leído y comentado en diferentes etapas de mi proceso de investigación y escritura. Le agradezco por haberme mostrado el cuidado, no solo desde la teoría, sino permitiéndome sentirlo durante nuestras conversaciones. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/12/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

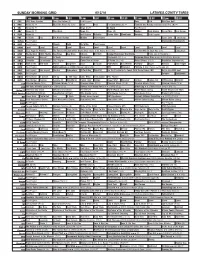

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/12/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula One Racing Canadian Grand Prix. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Underworld: Evolution (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Easy Yoga for Arthritis The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Eat Dirt With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Carpenters 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Louder Than Love: The Grande Pavlo Live in Kastoria Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Flashpoint Å Flashpoint (TV14) Å Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner. -

Mendez V. Westminster Resources Museum of Tolerance

Research Handout: Mendez v. Westminster Resources BOOKS Mendez v. Westminster: School Desegregation and Mexican- American Rights ($17.95) by Philippa Strum Details the famous case with narratives, personality portraits, and case analyses. This is a good resource for the teacher in terms of the court case. ISBN# 978-0-7006-1719-7 University Press of Kansas (785) 864-4155 www.kansaspress.ku.edu The U.S. Postal Service released this stamp in 2007 to commemorate Mendez v. Westminister. Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation ($11.98) by Duncan Tonatiuh Is a children’s picture book that beautifully synthesizes the story of this important case in United States civil rights history. ISBN# 978-1419710544 Harry N. Abrams (212) 206-7715 www.abramsbooks.com Sylvia & Aki ($6.99) by Winifred Conkling Tells the remarkable story of young Sylvia Mendez and Aki Munemitsu and how their lives intersect on a Southern California farm. ISBN# 978-1582463452 Random House Kids (212) 572-2232 www.randomhousekids.com museum of tolerance Research Handout: Mendez v. Westminster Resources ON THE INTERNET BEFORE BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION THERE WAS MENDEZ V. WESTMINSTER http://blogs.loc.gov/law/2014/05/before-brown-v-board-of-education-there-was-mendez-v-westminster/ This online archive from The Library of Congress delves into this lesser-known case that was instrumental for the American civil rights movement and desegregation of public schools. MENDEZ V. WESTMINSTER HISTORY http://www.sylviamendezinthemendezwestminster.com This website is about Sylvia Mendez, the daughter of Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez. She tells their story as a dedicated speaker and champion of change.