THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pieśniarz Warszawy, Czyli Stolica Pełna Muzycznych Szlagierów

Pieśniarz Warszawy, czyli stolica pełna muzycznych szlagierów Hanna Wach Adresat zajęć: uczniowie szkoły ponadpodstawowej, klasa II. Rodzaj zajęć: historia, koło historyczne. Cel ogólny zajęć: Kształtowanie umiejętności syntetyzowania wiedzy w czasie i przestrzeni historycznej oraz w ciągach problemowych. Pogłębienie zainteresowań historycznych uczniów, budzenie ciekawości poznawczej dotyczącej przeszłości. Cele szczegółowe: Uczeń: analizuje wydarzenia, zjawiska i procesy historyczne w kontekście epoki; sytuuje wydarzenia i zjawiska historyczne w czasie, porządkuje je, dostrzega zmiany w życiu społecznym oraz ciągłość w rozwoju kulturowym i cywilizacyjnym; dokonuje selekcji i hierarchizacji oraz integruje pozyskane informacje z różnych źródeł wiedzy. Metody pracy: metoda eksponująca: projekcja filmu, dyskusja dydaktyczna, poga- danka, drama (temat: „Głos warszawskiej kamienicy”), analiza źródeł w tym: ikono- grafii, zdjęć, analiza planu. Formy pracy: praca w grupach, praca indywidualna, praca z całą klasą. Środki i materiały dydaktyczne: plan Warszawy z 1934 r., ilustracje przedstawia- jące ulice, place, kamienice, podwórka-studnie przedwojennej Warszawy, ilustracje przedstawiające plakaty i programy kabaretów, rewii, ilustracje przedstawiające ka- barety i teatrzyki rewiowe przedwojennej Warszawy, zdjęcia celebrytów przedwojen- nej Warszawy, ilustracje przedstawiające menu w restauracjach, barach i kawiarniach, plakaty. Słowa kluczowe: kabarety, szlagiery, przedwojenna Warszawa, ballada podwórzo- wa, lata 30. Czas: 1 godzina lekcyjna -

Szmonces — Ten Specyficzny Genre Kabaretowy — Jak Go Określił Kazimierz Krukowski

http://dx.doi.org/10.17651/socjolinG.33.15 socjolingwistyka XXXiii, 2019 pl issn 0208-6808 e-issn 2545-0468 anna kRasowska uniwersytet kardynała stefana wyszyńskiego w Warszawie orcid: 0000-0002-5761-8317 fleksyjne wykładniki stylizacji na polszczyznę żydów w przedwojennym szmoncesie kabaretowym słowa kluczowe: stylizacja językowa, fleksja, polszczyzna Żydów, szmonces, kabaret w polsce. stReszczenie artykuł jest poświęcony stylizacji językowej w przedwojennych szmoncesach kabaretowych. przyjmując perspektywę lingwistyczną, autorka analizuje zjawiska fleksyjne, które stały się językową kanwą szmonce- sów: błędy związane z niedostateczną znajomością polszczyzny oraz interferencje wewnętrzne i zewnętrzne (z językiem jidysz). W tekstach kabaretowych zabiegi te pełnią funkcję identyfikacyjną (wskazują na ży- dowskiego bohatera utworu) i gatunkotwórczą, służą także wywołaniu efektu komicznego. analiza środków wykorzystanych przez autorów szmoncesów jest rozszerzeniem i uzupełnieniem badań nad polszczyzną Żydów w tekstach literackich i ludowych, które w latach 80. XX w. prowadziła Maria brzezina. szmonces kaBaRetowy szmonces — ten specyficznygenre kabaretowy — jak go określił kazimierz krukowski (1982: 187), zajmuje szczególną pozycję w historii polskich teatrzyków rewiowych i kabaretów okresu międzywojennego. etymologii samej nazwy poszukiwać należy w języku jidysz, w którym wyraz szmonce oznacza sensu largo ‘głupotę, bzdurę, bła- hostkę, nonsens’, w węższym zaś rozumieniu staje się synonimem dowcipu, kawału. pierwotnie szmoncesem nazywano wywodzący się z żydowskiego folkloru rodzaj twórczości oralnej — krótką opowiastkę zakończoną paradoksalną pointą (cała i in. 2000: 336), w której ujawniał się charakterystyczny dla tej społeczności sposób rozu- mowania i żartowania. w kontekście twórczości literacko-kabaretowej nazwa szmonces pojawiła się naj- prawdopodobniej w roku 1921, w jednej z recenzji programu Qui pro Quo, zamiesz- czonej w „robotniku” — jej autor określił tym mianem humorystyczny dialog Cymes i Cures (M.l. -

Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe

Vita Mathematica 18 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Vita Mathematica Volume 18 Edited by Martin MattmullerR More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/4834 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Author Hugo Steinhaus (1887–1972) Translator Abe Shenitzer Brookline, MA, USA Editors Robert G. Burns York University Dept. Mathematics & Statistics Toronto, ON, Canada Irena Szymaniec Wrocław, Poland Aleksander Weron The Hugo Steinhaus Center Wrocław University of Technology Wrocław, Poland Vita Mathematica ISBN 978-3-319-21983-7 ISBN 978-3-319-21984-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-21984-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954183 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Stanislaw Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas

Jens Herlth, Edward M. Świderski (eds.) Stanisław Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas Lettre Jens Herlth, Edward M. Świderski (eds.) with assistance by Dorota Kozicka Stanisław Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas Transnational Perspectives on the Intellectual Field in Twentieth-Century Poland and Beyond This volume is one of the outcomes of the research project »Standing in the Light of His Thought: Stanisław Brzozowski and Polish Intellectual Life in the 20th and 21st Centuries« funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project no. 146687). The publication of this book was made possible thanks to the generous support of the »Institut Littéraire Kultura«. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. -

Nihil Novi #3

The Kos’ciuszko Chair of Polish Studies Miller Center of Public Affairs University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia Bulletin Number Three Fall 2003 On the Cover: The symbol of the KoÊciuszko Squadron was designed by Lt. Elliot Chess, one of a group of Americans who helped the fledgling Polish air force defend its skies from Bolshevik invaders in 1919 and 1920. Inspired by the example of Tadeusz KoÊciuszko, who had fought for American independence, the American volunteers named their unit after the Polish and American hero. The logo shows thirteen stars and stripes for the original Thirteen Colonies, over which is KoÊciuszko’s four-cornered cap and two crossed scythes, symbolizing the peasant volunteers who, led by KoÊciuszko, fought for Polish freedom in 1794. After the Polish-Bolshevik war ended with Poland’s victory, the symbol was adopted by the Polish 111th KoÊciuszko Squadron. In September 1939, this squadron was among the first to defend Warsaw against Nazi bombers. Following the Polish defeat, the squadron was reformed in Britain in 1940 as Royal Air Force’s 303rd KoÊciuszko. This Polish unit became the highest scoring RAF squadron in the Battle of Britain, often defending London itself from Nazi raiders. The 303rd bore this logo throughout the war, becoming one of the most famous and successful squadrons in the Second World War. The title of our bulletin, Nihil Novi, invokes Poland’s ancient constitution of 1505. It declared that there would be “nothing new about us without our consent.” In essence, it drew on the popular sentiment that its American version expressed as “no taxation without representation.” The Nihil Novi constitution guar- anteed that “nothing new” would be enacted in the country without the consent of the Parliament (Sejm). -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Accommodation, Collaboration, and Resistance in Poland, 1939- 1947: a Theory of Choices and the Methodology of a Case Study 1

1 Marek Jan Chodakiewicz Accommodation, Collaboration, And Resistance in Poland, 1939- 1947: A Theory of Choices and the Methodology of a Case Study 1 A human being virtually always has a choice of how to conduct himself. Depending on the circumstances and conditions, a man can choose to behave actively or passively, atrociously or decently, and, exceptionally, even heroically. Moreover, one can display in succession any or all of the aforementioned characteristics. The innate attributes and handicaps of an individual inform the choices but do not guarantee the outcomes. That means that, at a certain point, a decent human being can behave atrociously, and vice versa. This concerns in particular human behavior in the extremity of terror. However, rather than suggesting that human behavior is arbitrary and unpredictable, I would like to propose that human behavior is a result of choices. How I arrived at these conclusions is the topic of the present discussion. I shall discuss first the methodology of my inquiry and then I shall elaborate on my discoveries. The Scientific Laboratory Scientific experiments are usually performed in a laboratory. As any biologist, chemist, or physicist can attest, sometimes the practical application of various scientific theories in the laboratory renders them null and void. At other times, however, scientific discoveries achieved in the controlled environment of the laboratory prove problematic at best and worthless at the extreme, if applied in the outside world. 1 I would like to dedicate my lecture to the memory of Professor Stanisław Blejwas, a teacher and a friend. 2 Throughout the ages the world has served as a giant laboratory for social scientists, historians in particular. -

Potato - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Potato - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read View source View history Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. Main page Potato Contents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Featured content Current events "Irish potato" redirects here. For the confectionery, see Irish potato candy. Random article For other uses, see Potato (disambiguation). Donate to Wikipedia The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum Interaction of the Solanaceae family (also known as the nightshades). The word potato may Potato Help refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, About Wikipedia there are some other closely related cultivated potato species. Potatoes were Community portal first introduced outside the Andes region four centuries ago, and have become Recent changes an integral part of much of the world's cuisine. It is the world's fourth-largest Contact Wikipedia food crop, following rice, wheat and maize.[1] Long-term storage of potatoes Toolbox requires specialised care in cold warehouses.[2] Print/export Wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to [3] Uruguay. The potato was originally believed to have been domesticated Potato cultivars appear in a huge variety of [4] Languages independently in multiple locations, but later genetic testing of the wide variety colors, shapes, and sizes Afrikaans of cultivars and wild species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area -

Is the Name “Polish Death Camps” a Misnomer?

Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal 95 Is the Name “Polish Death Camps” a Misnomer? Jacek Gancarson / e-mail: [email protected] The Home Army Cichociemni Paratroopers Foundation, Warsaw, Poland Natalia Zaitceva / e-mail: [email protected] The Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia, St. Petersburg, Russia Gancarsom, J. – Zaitceva, N. (2019). Is the Name “Polish Death Camps” a Misnomer? Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal, 11/2, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.5817/cphpj-2019-022 The purpose of the study is a historical-linguistic analysis of the ambiguous name “Polish death camps” (or “Polish concentration camps”), which for the last thirty years has led to conflicting assessments among politicians, journalists and historians, and in some cases being considered as a term. In order to make an accurate assessment of this name, and to clarify the question of the correctness/incorrectness of its use and come to a conclusion about the linguistic suitability/unsuitability to consider it a term, the authors study the new evidence by historians, interviews with public and political figures, and in particular, for the first time investigate the original editorial material where the name was formulated. In the course of the study, the true source of the name “Polish death camps” was first disclosed and a comprehensive history of its use was presented. Basing on gathered material the conclusion was made that the name is linguistically incorrect and can not be used as a term. Key words: Polish death camps; language -

Thanks to William Szych for Starting This Reading List. Most of the Books Below Can Be Found on Amazon Or Other Sites Where

Thanks to William Szych for starting this reading list. Most of the books below can be found on Amazon or other sites where you can read reviews of the books (Google Search). Remember you can usually request your local library to get books for you through regional book-lending agreements. If you know of other books that you think should be added, let us know. This list includes some works of historical fiction. 1. 22 Britannia Road, a novel by Amanda Hodgkinson 2. 303 Squadron: The Legendary Battle of Britain Fighter Squadron 3. A Death in the Forest (Poland’s Daughter: A Story of Love, War, and Exile) by Daniel Ford 4. A Long Long Time Ago and Essentially True, by Brigid Pasulka 5. A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising, by Miron Bialoszewski 6. A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II. Lynne Olson and Stanley Cloud 7. A Secret Life: The Polish Officer, His Covert Mission, and the Price He Paid to Save His Country, by Benjamin Weiser 8. A World Apart: Imprisonment in a Soviet Labor Camp During World War II 9. An Army in Exile—the Story of the Second Polish Corps, by Lt. General W. Anders 10. Andrew Bienkowski: One life to Give: A Path to Finding Yourself by Helping Others 11. Andrzej Pityński Sculpture. Anna Chudzik (Editor), Andrzej K. Olszewski, Irena Grzesiuk-Olszewska (Introduction) 12. As Far As My Feet Will Carry Me by Josef Bauer 13. Bieganski: The Brute Polak Stereotype in Polish-Jewish Relations and American Popular Culture by Danusha Goska 14. -

Goat’S Place in History

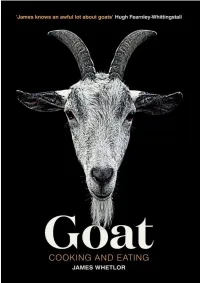

Publishing Director and Editor: Sarah Lavelle Designer: Will Webb Recipe Development and Food Styling: Matt Williamson Photographer: Mike Lusmore Additional Food Styling: Stephanie Boote Copy Editing: Sally Somers Production Controller: Nikolaus Ginelli Production Director: Vincent Smith First published in 2018 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing Quadrille 52–54 Southwark Street London SE1 1UN quadrille.com Text James Whetlor 2018 Photography Mike Lusmore 2018 Image 1 University of Manchester 2018 Image 2 Farm Africa / Nichole Sobecki 2018 Design and layout Quadrille Publishing Limited 2018 eISBN: 978 1 78713 279 5 Contents Title Page Foreword by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall Introduction Ötzi the Iceman The goat’s place in history Goats and modern farming Goats on the menu Leather Farm Africa Recipes Slow Quick Cooks Over Fire Roast Baked Basics Acknowledgements Index Recipe index Foreword There’s often a great deal to be sorry about in the world of modern food production. Indeed, there are so many serious problems, worrying issues and shameful practices that it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. But there are also innovations, solutions and great ideas – things to be celebrated and enjoyed that offer a fantastic counterpoint to the bad news. These bright, good ideas offer the way forward and it’s imperative that we throw a spotlight on them – which is why I’m delighted to be introducing this, James’s book. I first knew James as a talented chef in the River Cottage kitchen. He’s now also proved himself a writer and a successful ethical businessman. Cabrito, James’s company, was born after he took an uncompromising look at a tough problem within our food system – the wholesale slaughter of the male offspring of dairy goats soon after birth. -

Catalogo Giornate Del Cinema Muto 2016

ASSOCIAZIONE CULTURALE Chiba, Max Laiguillon, Eric Lange (Lobster Films); “LE GIORNATE DEL CINEMA MUTO” Lenny Borger. Germania: Thilo Gottschling, Andreas Lautil, Soci fondatori Matteo Lepore (ARRI Media GmbH); Karl Griep, Paolo Cherchi Usai, Lorenzo Codelli, Evelyn Hampicke, Egbert Koppe, Julika Kuschke Piero Colussi, Andrea Crozzoli, Luciano De (Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, Berlin); Hans-Michael Giusti, Livio Jacob, Carlo Montanaro, Mario Bock (CineGraph, Hamburg); Dirk Foerstner, Quargnolo†, Piera Patat, Davide Turconi† Martin Koerber (Deutsche Kinemathek, Presidente Berlin); Anke Mebold, Michael Schurig, Thomas Livio Jacob Worschech (Deutsches Filminstitut – DIF); Direttore emerito Andreas Thein (Filmmuseum Düsseldorf); David Robinson Stefan Drössler (Filmmuseum München); Ralf Forster (Filmmuseum Potsdam); Anke Wilkening Direttore (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung); Christiane Jay Weissberg Reuter (Spielzeugmuseum der Stadt Tübingen); Lea-Aimee Frankenbach; Jeanpaul Goergen; Ringraziamo sentitamente per aver collaborato Megumi Hayakawa; Martin Loiperdinger. al programma: Giappone: Hisashi Okajima, Akira Tochigi Argentina: Fernando Martín Peña (Filmoteca (National Film Center of The National Museum of Buenos Aires); Paula Félix-Didier, Leandro Listorti Modern Art, Tokyo); Hiroshi Komatsu; (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken, Buenos Johan Nordström. Aires). Italia: Flavia Barretti, Andrea Meneghelli, Australia: Joel Archer (Golden Oldies Cinema, Davide Pozzi, Elena Tammaccaro (Cineteca di Brisbane); Sally Jackson, Meg Labrum, Michael