PDF (Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing, and New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2019

The definitive source of news and analysis of the global fintech sector | February 2019 www.bankingtech.com SUPERSTRUCTURES Fintech reaches new heights CASE STUDY: CITIZENS BANK US heavyweight pivots for digital era FOOD FOR THOUGHT: CAREER CHOICES The Venn diagram of doom FINTECH FUTURES IN THIS ISSUE THEM US Contents NEWS 04 The latest fintech news from around the globe: the good, the bad and the ugly. 18 Banking Technology Awards The glamour, the winners and the celebrations. 23 Focus: intraday liquidity Are banks ready to meet the ECB’s latest expectations? 24 Interview: Pavel Novak, Zonky P2P lender on a “mission possible”. 26 Focus: data How DNB uses data to reconnect with customers. 30 Analysis: openfunds Admirable data standardisation efforts for the funds industry. 32 Case study: Citizens Bank US’s 13th largest bank embraces digital era. 38 Food for thought Making career choices and the Venn diagram of doom. They struggle with Fintech complexity. We see straight to your goal. We leverage proprietary knowledge and technology to solve complex regulatory challenges, create new products 40 Comment What would a recession mean for fintech? and build businesses. Our unique “one fi rm” approach brings to bear best-in-class talent from our 32 offi ces worldwide—creating teams that blend global reach and local knowledge. Looking for a fi rm that can help keep 42 Interview: Javier Santamaría, EPC your business moving in the right direction? Visit BCLPlaw.com to learn more. Happy one year anniversary, SEPA Instant Credit Transfer! REGULARS 44 -

VISA Europe AIS Certified Service Providers

Visa Europe Account Information Security (AIS) List of PCI DSS validated service providers Effective 08 September 2010 __________________________________________________ The companies listed below successfully completed an assessment based on the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). 1 The validation date is when the service provider was last validated. PCI DSS assessments are valid for one year, with the next annual report due one year from the validation date. Reports that are 1 to 60 days late are noted in orange, and reports that are 61 to 90 days late are noted in red. Entities with reports over 90 days past due are removed from the list. It is the member’s responsibility to use compliant service providers and to follow up with service providers if there are any questions about their validation status. 2 Service provider Services covered by Validation date Assessor Website review 1&1 Internet AG Internet payment 31 May 2010 SRC Security www.ipayment.de processing Research & Consulting Payment gateway GmbH Payment processing a1m GmbH Payment gateway 31 October 2009 USD.de AG www.a1m.biz Internet payment processing Payment processing A6IT Limited Payment gateway 30 April 2010 Kyte Consultants Ltd www.A6IT.com Abtran Payment processing 31 July 2010 Rits Information www.abtran.com Security Accelya UK Clearing and Settlement 31 December 2009 Trustwave www.accelya.com ADB-UTVECKLING AB Payment gateway 30 November 2009 Europoint Networking WWW.ADBUTVECKLING.SE AB Adeptra Fraud Prevention 30 November 2009 Protiviti Inc. www.adeptra.com Debt Collection Card Activation Adflex Payment Processing 31 March 2010 Evolution LTD www.adflex.co.uk Payment Gateway/Switch Clearing & settlement 1 A PCI DSS assessment only represents a ‘snapshot’ of the security in place at the time of the review, and does not guarantee that those security controls remain in place after the review is complete. -

The Factors Influencing the Adoption of In-Store Mobile Payments: a Validation and Extension Study

THE FACTORS INFLUENCING THE ADOPTION OF IN-STORE MOBILE PAYMENTS: A VALIDATION AND EXTENSION STUDY ZANÉ DIPPENAAR University of the Free State E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- The aim of this study is to identify the factors influencing the adoption of in-store mobile payments. The development of mobile-phone technology is changing consumer demand and behaviors. Consequently, businesses are becoming ever more mobile orientated, offering mobile shopping, mobile payments and in-store mobile payments to consumers. The goals of in-store mobile payments are to i) save consumers time and ii) to facilitate cashless transactions. Regardless of the fact that businesses offer in-store mobile payments and the convenience thereof, consumers adapt slowly to this offering. Thus, the research question that emerged is “What are the factors influencing the adoption of in-store mobile payments?” The hypotheses of this study examine the relationships between the influencing factors and consumers’ behavioral intention to use in-store mobile payments. The empirical study implemented a non-probability sample was used, with the sample comprising of students from the Business Management Department at the University of the Free State who owns a smartphone, but has no prior experience with in-store mobile payments. The results of the study indicated that initial trust, self-efficacy, relative advantage and compatibility have a significant positive influence on the intention to adopt in- store mobile payments. Furthermore, perceived risk was found to have a significant negative influence on the intention to use mobile payments in-store. The findings of the study provide guidance for developers and marketers of in-store mobile payments in developing a marketing strategy that would enhance the use of in-store mobile payments. -

Telefónica's 7Th Investor Conference Matthew

Telefónica’s 7th Investor Conference October 9th, 2009 Matthew Key - Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Telefónica Europe “Continued outperformance from a broader business” transcript Important Notice: Although we try to accurately reflect speeches delivered, the actual speech as it was delivered may deviate from the script made available on our website 2 7th Investor Conference – “Continued outperformance from a broader business” transcript Thanks, Maria. What I was going to do over the next 25 minutes is tell you in Telefónica Europe how we've delivered in the past and actually how we're going to deliver our commitments as part of Telefónica commitments. What I'm going to start by doing is just talking a little bit about our performance and how we performed against the competition. So the market is fast changing. But what we've managed to do, I think, is move ahead of the market in Europe. And the key thing we do here is we make efficiency gains continuously so we don't just respond to market conditions. We continually drive efficiency gains and we continually drive in the customer experience. And we continue to invest in the customer whatever the market environment is. What you can see on the first chart is absolute evidence of that. So if you look at the 12-month to June '09 actually we drove about 44% of the net adds across our markets. The great news is that every one of my businesses produced a higher share in the 12-month to June '09 than they did in the 12-month to June '07. -

Presentation 27 May 2010

PayPoint plc Preliminary Results Presentation 27 May 2010 Strictly private and confidential Agenda • Highlights & Strategy • Operational Review • Financial Review • Summary and Outlook • Q&A 2 Highlights & Strategy Dominic Taylor Chief Executive 3 Established and developing business streams Established business streams: – Generate the group’s profits and cash flows – Provide unique retail/internet proposition to clients – Strongly differentiated to clients and retailers – With significant barriers to entry Developing business streams: – In large markets that have strong growth potential, with opportunities to accelerate growth – Core to PayPoint’s strategy to broaden payment capability and extend differentiation – Leverage established business streams – On clear path to profitability – Diversify risk across a broader and more balanced business 4 PayPoint highlights • Established business streams delivered to plan: – Over 650 net additions to UK retail network, reinforcing our value to retailers – Strong growth in retail services (transactions 23% up) – 22% transaction growth in internet payments – New value added services • Investment in developing business streams: – 3,400 Collect+ sites; 13 clients with many more interested – 900 new Romanian bill-pay sites – Six-fold increase in bill pay transactions in Romania – PayByPhone acquisition opens new geographies and capability • Large growth markets for developing businesses 5 Camelot What is proposed? Our position: • Camelot seeking to enter our UK • Robust response, underpinned by retail -

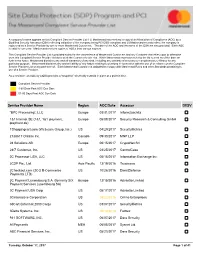

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

Fintech Monthly Market Update | July 2021

Fintech Monthly Market Update JULY 2021 EDITION Leading Independent Advisory Firm Houlihan Lokey is the trusted advisor to more top decision-makers than any other independent global investment bank. Corporate Finance Financial Restructuring Financial and Valuation Advisory 2020 M&A Advisory Rankings 2020 Global Distressed Debt & Bankruptcy 2001 to 2020 Global M&A Fairness All U.S. Transactions Restructuring Rankings Advisory Rankings Advisor Deals Advisor Deals Advisor Deals 1,500+ 1 Houlihan Lokey 210 1 Houlihan Lokey 106 1 Houlihan Lokey 956 2 JP Morgan 876 Employees 2 Goldman Sachs & Co 172 2 PJT Partners Inc 63 3 JP Morgan 132 3 Lazard 50 3 Duff & Phelps 802 4 Evercore Partners 126 4 Rothschild & Co 46 4 Morgan Stanley 599 23 5 Morgan Stanley 123 5 Moelis & Co 39 5 BofA Securities Inc 542 Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters). Announced Locations Source: Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters) Source: Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters) or completed transactions. No. 1 U.S. M&A Advisor No. 1 Global Restructuring Advisor No. 1 Global M&A Fairness Opinion Advisor Over the Past 20 Years ~25% Top 5 Global M&A Advisor 1,400+ Transactions Completed Valued Employee-Owned at More Than $3.0 Trillion Collectively 1,000+ Annual Valuation Engagements Leading Capital Markets Advisor >$6 Billion Market Cap North America Europe and Middle East Asia-Pacific Atlanta Miami Amsterdam Madrid Beijing Sydney >$1 Billion Boston Minneapolis Dubai Milan Hong Kong Tokyo Annual Revenue Chicago New York Frankfurt Paris Singapore Dallas -

Financial Technology Sector Overview of Market Activity in the Financial Technology Sector William Blair & Company

Quarterly Update Q1 2015 Financial Technology Sector Overview of Market Activity in the Financial Technology Sector William Blair & Company Financial Technology Sector – First Quarter 2015 Update M&A and capital markets activity remained strong during the first quarter of 2015, particularly in the United States. In fact, U.S. stock indices marked all-time highs during the quarter and deal-making activity continued its upward trajectory, propelled by improving confidence among consumers and corporate executives, low-cost credit, and record levels of cash. While market participants largely ignored the prospect of rising interest rates, a collapsing energy sector, global currency concerns, and continued economic uncertainty abroad, this could be an area of concern moving into the second quarter of 2015. One of the most prominent storylines within the financial technology sector in the first quarter was the escalating bets made on payments solutions by the likes of tech giants Apple, Google, and Samsung. The release of Apple Pay unilaterally raised the stakes across the industry and was a catalyst for a wave of high-profile announcements, including Samsung’s acquisition of LoopPay, Google’s acquisition of Softcard, and PayPal’s acquisition of Paydiant. Traditional payments providers are thus being further pressured to accelerate innovation and expand international reach, which has in turn refocused corporate strategies away from building domestic scale and vertical plays toward acquiring differentiated, earlier-stage, technology platforms with global capabilities. Global’s acquisition of Realex, Worldpay’s acquisition of SecureNet, and MasterCard’s acquisition of TNS’s gateway are recent examples of this trend, which we believe will be a significant driver of sector M&A activity going forward. -

SIM City How the Machine to Machine Market IS Taking Shape

the future of wireless ISSUE 170 APRIL 2011 featuring Backhaul: Keeping the traffic moving. Banking on NFC: MNOs look to retain their place in mobile financial services. SIM City HOW THE MACHINE TO MACHINE MARKET IS TAKING SHAPE OFC_MCI170.indd 1 31/03/2011 14:39 MCI_Feb11_ipaccess.pdf 2 26/01/2011 18:52 ipaccess.com nano3G™ The end-to-end picocell and femtocell solution – New S class femtocell for smaller offices and shops – E class picocells for in-building coverage & capacity – Scale your up-front integration to fit your budget – Based on proven femtocell technology – A complete turnkey solution optimised for business and indoor public access FRONT Editorial 04 CONTENTS APRIL11 Analysis 06 Deutsche Telekom is to play in another large scale consolidation. This time the US arm of its mobile operation T-Mobile is the subject of an acquisition bid from US market leader AT&T. If successful the deal will give AT&T 43 per cent of the US mobile market and more than 130 million customers so it’s no surprise that it has already drawn some objections. Meanwhile industry relations between China and the West are getting a touch fraught, making life difficult for the likes of Huawei. In an extraordinary open letter, one senior Huawei executive challenged the firm’s detractors to | 16 MACHINE TO MACHINE back up the accusations that the firm represents a If some players are to be believed, in the not security threat. But the protectionism isn’t all one way. too distant future we will live in a world of 50 billion connected devices. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT www.telefonica.com 2010 ANNUAL REPORT Summary Vision p 04-09 Talent p 10-21 Commitment p 22-49 Strength p 50-125 02 Telefónica, S.A. Annual Report 2010 ‘Telefónica’s vision is to make the possibilities offered by this new digital world real, and to be one of the leaders in this area’, says the Executive Chairman, César Alierta, in his letter to shareholders. Telefónica has a suitable structure in order to make the most of synergies as a global company that is already present in 25 countries. Its Board of Directors, its Management Team and its more than 285,000 Professionals guarantee the good government and management of the Company and the performance of the work plans included in the bravo! programme (strategic plan for 2010-2012). In 2010, Telefónica, driven by the acquisition of the Brazilian operator Vivo, increased the scale of its operations, once again obtaining solid results, and fulfi lling the commitments made in the market. Progress was possible thanks to improvements in customer experience, based on a new brand strategy; to the promotion provided by innovation in order to capture the opportunities for growth provided by the digital market; and to the improvement of operating effi ciency. All this, together with a strong range of strategic alliances and our leadership in corporate sustainability, has made Telefónica the most admired company in the telecommunications industry in 2010. The 2010 results demonstrate Telefónica’s strength and its capacity to generate trust in the markets with a sensible risk management policy . Annual Report 2010 Telefónica, S.A. -

Ingenico Group Registration Document 2016

2016 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT CONTENTS CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE 3 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL PROFILE 4 5 STATEMENTS DECEMBER 31, 2016 131 KEY FIGURES 6 5.1 Consolidated income statement 132 INGENICO GROUP IN THE WORLD IN 2016 8 5.2 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 133 5.3 Consolidated statement of fi nancial position 134 2016 IN 8 HIGHLIGHTS 10 5.4 Consolidated cash fl ow statement 136 HISTORY 12 5.5 Consolidated statement of change in equity 138 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART 5.6 Notes to the consolidated fi nancial statements 139 (AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2016) 14 5.7 Statutory auditors’ report on the consolidated fi nancial statements 193 PRESENTATION 1 OF THE GROUP 17 PARENT COMPANY FINANCIAL 6 STATEMENTS AT DECEMBER 31, 2016 195 1.1 Activity & strategy 18 1.2 Risk factors 28 6.1 Assets 196 6.2 Liabilities 197 6.3 Profi t and loss account 198 6.4 Notes to the parent company fi nancial statements 199 CORPORATE SOCIAL 2 RESPONSIBILITY 37 6.5 Statutory auditors’ report on the parent company annual fi nancial statements 219 2.1 CSR for Ingenico Group 38 6.6 Five-year fi nancial summary 220 2.2 Reporting scope and method 42 2.3 The Ingenico Group community 45 2.4 Ingenico Group’s contribution to society 53 COMBINED ORDINARY AND 2.5 Ingenico Group’s environmental approach 64 7 EXTRAORDINARY SHAREHOLDERS’ 2.6 Report by the independent third party, on the MEETING OF MAY 10, 2017 221 consolidated human resources, environmental and social information included in the management report 75 7.1 Draft agenda and proposed resolutions -

Tokyo 100Ventures 101 Digital 11:FS 1982 Ventures 22Seven 2C2P

Who’s joining money’s BIGGEST CONVERSATION? @Tokyo ACI Worldwide Alawneh Exchange Apiture Association of National Advertisers 100Ventures Acton Capital Partners Alerus Financial AppBrilliance Atlantic Capital Bank 101 Digital Actvide AG Align Technology AppDome Atom Technologies 11:FS Acuminor AlixPartners AppFolio Audi 1982 Ventures Acuris ALLCARD INC. Appian AusPayNet 22seven Adobe Allevo Apple Authomate 2C2P Cash and Card Payment ADP Alliance Data Systems AppsFlyer Autodesk Processor Adyen Global Payments Alliant Credit Union Aprio Avant Money 500 Startups Aerospike Allianz Apruve Avantcard 57Blocks AEVI Allica Bank Limited Arbor Ventures Avantio 5Point Credit Union AFEX Altamont Capital Partners ARIIX Avast 5X Capital Affinipay Alterna Savings Arion bank AvidXchange 7 Seas Consultants Limited Affinity Federal Credit Union Altimetrik Arroweye Solutions Avinode A Cloud Guru Affirm Alto Global Processing Aruba Bank Aviva Aadhar Housing Finance Limited African Bank Altra Federal Credit Union Arvest Bank AXA Abercrombie & Kent Agmon & Co Alvarium Investments Asante Financial Services Group Axway ABN AMRO Bank AgUnity Amadeus Ascension Ventures AZB & Partners About Fraud AIG Japan Holdings Amazon Ascential Azlo Abto Software Aimbridge Hospitality American Bankers Association Asian Development Bank Bahrain Economic Development ACAMS Air New Zealand American Express AsiaPay Board Accenture Airbnb Amsterdam University of Applied Asignio Bain & Company Accepted Payments aircrex Sciences Aspen Capital Fund Ballard Spahr LLP Acciones y Valores