Logoi of the First Overseas American Missionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Exploring Christianity in Asia I 12 Oct-24 Dec 2020 11-Weeks Online Zoom │ Videos Programme

EXPLORING CHRISTIANITY IN ASIA I 12 OCT-24 DEC 2020 11-WEEKS ONLINE ZOOM │ VIDEOS PROGRAMME WEEK 1WEEK 2WEEK 3WEEK 4WEEK 5 ) ) CT CT OCTOBER 12 OCTOBER 19 OCTOBER 26 NOVEMBER 2 NOVEMBER 9 12:00-13:30 24 O 25 O Gholamreza Raeisian (Mashhad) 4 Assaad Elias Kattan 7 Gudrun Löwner 10 Haila Manteghi 13 Richard Fox Young (Münster) (Bangalore) (Münster) (Princeton, USA) TILL Norbert Hintersteiner (Münster) FROM Contemporary Christian Views Interreligious Dialogue in Indian The Interactions Between Christianity and Conversion, (Iranian time) Opening and Practicalities of Islam in the Arab World: A Arts from the Mogul Times till Catholic Missionaries and the with Special Reference to South 19:30-21:30 Paradigm Shift? Today Shi’a Clerics in the Safavid Asia 1 Manfred Hutter Persia (16th-18th Cent.) (Bonn) 19:30- 21:30 ( Christianity as a Minority Religion in 5 Sebastien Peyrouse 8 Francesco Gusella 14 Rudolf Heredia 20:30-22:30 ( 11 Julian Strube Pre-Islamic Iran: Interactions with (Washington DC) (Münster) (Münster) (New Delhi, India) Zoroastrianism Christian Minorities on the Catholic Christianity in the Religious Universalism in Religious Disarmament: Politics Indian Ocean (1540-1640): A of Conversion ONDAY Central Asian Silk Roads 2 Herman Teule 19thCent. Bengal: Exchanges M Journey through 20 Objects (Leuven) Between Unitarians and Indian Christians in the Middle East: Reformers Their Interaction with the World of Islam OCTOBER 15 OCTOBER 22 OCTOBER 29 NOVEMBER 5 NOVEMBER 12 3 Assaad Elias Kattan 6 Daniel F. Pilario 9 Haila Manteghi 12 Julian Strube 15 Madlen Krüger (Münster) (Quezon City, Philippines) (Münster) (Münster) (Münster) Christian Perceptions of Islam Revisiting Historiographies: The Jesuits at the Mughal Court Religious Nationalism in Christianity in Myanmar – (Iranian time) among Arab-Speaking New Trajectories for Asian in India (15th-17th Cent) 19thCent. -

The Making of Modern Burma Thant Myint-U Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521780217 - The Making of Modern Burma Thant Myint-U Index More information Index Abhisha Husseini, 51 and local rebellions, 172, 173–4, 176 Afghanistan, 8, 22, 98, 102, 162 and modern Burma, 254 agriculture, 36, 37, 40, 44, 47, 119, 120, payment of, 121 122, 167, 224, 225, 236, 239; see also reforms, 111–12 cultivators Assam, 2, 13, 15–16, 18, 19, 20, 95, 98, 99, Ahom dynasty, 15–16 220 Aitchison, Sir Charles, 190–1 athi, 33, 35 Alaungpaya, King, 13, 17, 58, 59–60, 61, Ava (city), 17, 25, 46, 53, 54 70, 81, 83, 90, 91, 107 population, 26, 54, 55 Alaungpaya dynasty, 59, 63, 161 Ava kingdom, 2 allodial land, 40, 41 administration, 28–9, 35–8, 40, 53–4, Alon, 26, 39, 68, 155, 173, 175 56–7, 62, 65–8, 69, 75–8, 108–9, Amarapura, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 26, 51, 53, 115–18, 158–60, 165–6 54, 119, 127, 149 anti-British attitudes, 6–7, 99, 101–3 rice prices, 143 and Bengal, 94, 95, 96, 98, 99–100 royal library, 96 boundaries of, 9, 12, 24–5, 92, 101, Amarapura, Myowun of, 104–5 220 Amherst, Lord, 106 British attitudes to, 6, 8–9, 120, 217–18, Amyint, 36, 38, 175 242, 246, 252 An Tu (U), 242 and Buddhism, 73–4, 94, 95, 96, 97, 108, Anglo-Burmese wars, 2, 79 148–52, 170–1 First (1824–6), 18–20, 25, 99, 220 ceremonies, 97, 149, 150 Second (1852–3), 23, 104, 126 and China, 47–8, 137, 138, 141, 142, Third (1885), 172, 176, 189, 191–3 143, 144, 147–8 animal welfare, 149, 171 chronicles of, 79–83, 86, 240 appanages, 29, 53, 61–3, 68, 69, 72–3, 77, and colonial state, 219–20 107, 108, 231 commercial concessions, 136–7 reform of, -

5) Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Shinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle 2.Pmd

Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Hsinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle by Thaw Kaung King Bayinnaung (AD 1551-1581) is known and respected in Myanmar as a great war- rior king of renown. Bayinnaung refers to himself in the only inscription that he left as “the Conqueror of the Ten Directions”.1 but this epithet is not found in the main Myanmar chronicles or in the Ayedawbon texts. Professor D. G. E. Hall of Rangoon University wrote that “Bayinnaung was a born leader of men. the greatest ever produced by Burma. ”2 There is a separate Ayedawbon historical chronicle devoted specifically to the campaigns and achievements of Bayinnaung entitled Hsinbyumya-shin Ayedawbon.3 Ayedawbon The term Ayedawbon means “a historical account of a royal campaign” 4 It also means a chronicle which records the campaigns and achivements of great kings like Rajadirit, Bayinnaung and Alaungphaya. The Ayedawbon is a Myanmar historical text which records : (1) How great men of prowess like Bayinnaung consolidated their power and became king. (2) How these kings retained their power by military campaigns, diplomacy, alliances and 1. For the full text of The Bell Inscription of King Bayinnaung see Report of the Superintendent, Archaeological Survey, Burma . 1953. Published 1955. p. 17-18. For the English translations by Dr. Than Tun and U Sein Myint see Myanmar Historical Research Journal. no. 8 (Dec. 2001) p. 16-20, 23-27. 2. D. G. E. Hall. Burma. 2nd ed. London : Hutchinson’s University Library, 1956. p.41. 3. The variant titles are Hsinbyushin Ayedawbon and Hanthawadi Ayedawbon. 4. Myanmar - English Dictionary. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

The Dōgen Zenji´S 'Gakudō Yōjin-Shū' from a Theravada Perspective

The Dōgen Zenji´s ‘Gakudō Yōjin-shū’ from a Theravada Perspective Ricardo Sasaki Introduction Zen principles and concepts are often taken as mystical statements or poetical observations left for its adepts to use his/her “intuitions” and experience in order to understand them. Zen itself is presented as a teaching beyond scriptures, mysterious, transmitted from heart to heart, and impermeable to logic and reason. “A special transmission outside the teachings, that does not rely on words and letters,” is a well known statement attributed to its mythical founder, Bodhidharma. To know Zen one has to experience it directly, it is said. As Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright said, “The image of Zen as rejecting all forms of ordinary language is reinforced by a wide variety of legendary anecdotes about Zen masters who teach in bizarre nonlinguistic ways, such as silence, “shouting and hitting,” or other unusual behaviors. And when the masters do resort to language, they almost never use ordinary referential discourse. Instead they are thought to “point directly” to Zen awakening by paradoxical speech, nonsequiturs, or single words seemingly out of context. Moreover, a few Zen texts recount sacrilegious acts against the sacred canon itself, outrageous acts in which the Buddhist sutras are burned or ripped to shreds.” 1 Western people from a whole generation eager to free themselves from the religion of their families have searched for a spiritual path in which, they hoped, action could be done without having to be explained by logic. Many have founded in Zen a teaching where they could act and think freely as Zen was supposed to be beyond logic and do not be present in the texts - a path fundamentally based on experience, intuition, and immediate feeling. -

Buddhism in Myanmar a Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1

Buddhism in Myanmar A Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1. Earliest Contacts with Buddhism 2. Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu Kingdoms 3. Theravada Buddhism Comes to Pagan 4. Pagan: Flowering and Decline 5. Shan Rule 6. The Myanmar Build an Empire 7. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Notes Bibliography Preface Myanmar, or Burma as the nation has been known throughout history, is one of the major countries following Theravada Buddhism. In recent years Myanmar has attained special eminence as the host for the Sixth Buddhist Council, held in Yangon (Rangoon) between 1954 and 1956, and as the source from which two of the major systems of Vipassana meditation have emanated out into the greater world: the tradition springing from the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Thathana Yeiktha and that springing from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of the International Meditation Centre. This booklet is intended to offer a short history of Buddhism in Myanmar from its origins through the country's loss of independence to Great Britain in the late nineteenth century. I have not dealt with more recent history as this has already been well documented. To write an account of the development of a religion in any country is a delicate and demanding undertaking and one will never be quite satisfied with the result. This booklet does not pretend to be an academic work shedding new light on the subject. It is designed, rather, to provide the interested non-academic reader with a brief overview of the subject. The booklet has been written for the Buddhist Publication Society to complete its series of Wheel titles on the history of the Sasana in the main Theravada Buddhist countries. -

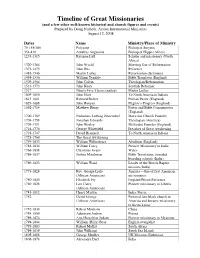

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Mandalay and Printing Press Industry.Pdf

Title Mandalay and the Printing Industry All Authors Yan Naing Lin Local Publication Publication Type Publisher (Journal name, Mandalay University Researh Journal, Vol. 7 issue no., page no etc.) Literature, a kind of aesthetic art, is an effective tool for enlightenment, entertainment and propagation. It also reveals the politics, economy, social conditions and cultural aspects of certain period. Likewise, the books distribute the religious, political and cultural ideologies throughout the world. The books play a crucial role in the history of human innovations. The invention of printing press is the most important milestone to distribute various literary works and scientific knowledge. Since the last days of the monarchical rule, King Mindon who realized the importance of literature in propagation of Buddhism and wellbeing of kingdom included the foundation of printing industry in his reformation works. He published the first newspaper of Mandalay to counterpoise the propagation of British from Lower Myanmar. Abstract However, the printing industry of Mandalay in the reigns of King Mindon and King Thibaw was limited in the Buddhist cultural norms and could not provided the knowledge of the people. During the colonial period, the printing industry of Mandalay transformed into the tool to boost the knowledge and nationalist sentiment of people. The Wunthanu movement, nationalist movement, anti-colonialist struggle and struggle for independence under the AFPFL leadership as well as the struggle for peace in post independence era in Upper Myanmar were instigated by the Mandalay printing industry. Nevertheless, the printing industry of Mandalay was gradually on the wane under Revolutionary Council Government which practiced strict censorship on the newspapers and other periodicals. -

In One Sacred Effort – Elements of an American Baptist Missiology

In One Sacred Effort Elements of an American Baptist Missiology by Reid S. Trulson © Reid S. Trulson Revised February, 2017 1 American Baptist International Ministries was formed over two centuries ago by Baptists in the United States who believed that God was calling them to work together “in one sacred effort” to make disciples of all nations. Organized in 1814, it is the oldest Baptist international mission agency in North America and the second oldest in the world, following the Baptist Missionary Society formed in England in 1792 to send William and Dorothy Carey to India. International Ministries currently serves more than 1,800 short- term and long-term missionaries annually, bringing U.S. and Puerto Rico churches together with partners in 74 countries in ministries that tell the good news of Jesus Christ while meeting human needs. This is a review of the missiology exemplified by American Baptist International Ministries that has both emerged from and helped to shape American Baptist life. 2 American Baptists are better understood as a movement than an institution. Whether religious or secular, movements tend to be diverse, multi-directional and innovative. To retain their character and remain true to their core purpose beyond their first generation, movements must be able to do two seemingly opposite things. They must adopt dependable procedures while adapting to changing contexts. If they lose the balance between organization and innovation, most movements tend to become rigidly institutionalized or to break apart. Baptists have experienced both. For four centuries the American Baptist movement has borne its witness within the mosaic of Christianity. -

00-Title JIABU (V.11 No.1)

The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities (JIABU) Vol. 11 No.1 (January – June 2018) Aims and Scope The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities is an academic journal published twice a year (1st issue January-June, 2nd issue July-December). It aims to promote research and disseminate academic and research articles for researchers, academicians, lecturers and graduate students. The Journal focuses on Buddhism, Sociology, Liberal Arts and Multidisciplinary of Humanities and Social Sciences. All the articles published are peer-reviewed by at least two experts. The articles, submitted for The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities, should not be previously published or under consideration of any other journals. The author should carefully follow the submission instructions of The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities including the reference style and format. Views and opinions expressed in the articles published by The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities, are of responsibility by such authors but not the editors and do not necessarily refl ect those of the editors. Advisors The Most Venerable Prof. Dr. Phra Brahmapundit Rector, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand The Most Venerable Xue Chen Vice President, Buddhist Association of China & Buddhist Academy of China The Most Venerable Dr. Ashin Nyanissara Chancellor, Sitagu International Buddhist Academy, Myanmar Executive Editor Ven. Prof. Dr. Phra Rajapariyatkavi Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand ii JIABU | Vol. 11 No.1 (January – June 2018) Chief Editor Ven. Phra Weerasak Jayadhammo (Suwannawong) International Buddhist Studies College (IBSC), Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand Editorial Team Ven. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand Prof. -

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar A Gift of Dhamma AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Tha Worship In Myanmar “(Most venerated and most popular Buddhist deity)” Om Mani Padme Hum.... Page 2 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Bodhisatta Loka Nat (Buddha Image on her Headdress is Amithaba Buddha) Loka Nat, Loka Byu Ha Nat Tha in Myanmar; Kannon, Kanzeon in Japan; Chinese, Kuan Yin, Guanshiyin in Chinese; Tibetan, Spyan-ras- gzigs in Tabatan; Quan-am in Vietnamese Page 3 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Introduction: Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisatta is the most revered Deity in Myanmar. Loka Nat is the only Mahayana Deity left in this Theravada country that Myanmar displays his image openly, not knowing that he is the Mahayana Deity appearing everywhere in the world in a variety of names: Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin, Kuan Shih Yin and Kannon. The younger generations got lost in the translation not knowing the name Loka Nat means one and the same for this Bodhisatta known in various part of the world as Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin or Kannon. He is believed to guard over the world in the period between the Gotama Sasana and Mettreyya Buddha sasana. Based on Kyaikhtiyoe Cetiya’s inscription, some believed that Loka Nat would bring peace and prosperity to the Goldenland of Myanmar. Its historical origin has been lost due to artistic creativity Myanmar artist. The Myanmar historical record shows that the King Anawratha was known to embrace the worship of Avalokitesvara, Loka Nat. Even after the introduction of Theravada in Bagan, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Lokanattha, Loka Byuhar Nat, Kuan Yin, and Chenresig, had been and still is the most revered Mahayana deity, today.