Poetry and Commentary RICHARD GOODSON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KAJIAN SEMIOTIKA) グースハウスが歌った「Goose House Phrase #7 Soundtrack?」というアルバムに おけるアイコン、インデックス、とシムボール 「記号研究」

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diponegoro University Institutional Repository IKON, INDEKS, DAN SIMBOL DALAM LIRIK LAGU ALBUM GOOSE HOUSE PHRASE #7 SOUNDTRACK? (KAJIAN SEMIOTIKA) グースハウスが歌った「Goose house Phrase #7 Soundtrack?」というアルバムに おけるアイコン、インデックス、とシムボール 「記号研究」 Skripsi Oleh: Afinda Rosa Husnia NIM 13050113130116 JURUSAN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS DIPONEGORO SEMARANG 2017 IKON, INDEKS, DAN SIMBOL DALAM LIRIK LAGU ALBUM GOOSE HOUSE PHRASE #7 SOUNDTRACK? (KAJIAN SEMIOTIKA) グースハウスが歌った「Goose house Phrase #7 Soundtrack?」というアルバムに おけるアイコン、インデックス、とシムボール 「記号研究」 Skripsi Diajukan untuk Menempuh Ujian Sarjana Program Strata I dalam Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: Afinda Rosa Husnia NIM 13050113130116 PROGRAM STUDI S-1 SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS DIPONEGORO SEMARANG 2017 HALAMAN PERNYATAAN Dengan sebenarnya, penulis menyatakan bahwa skripsi ini disusun tanpa mengambil bahan hasil penelitian, baik untuk memperoleh suatu gelar sarjana atau diploma yang sudah ada di universitas lain maupun hasil penelitian lainnya. Penulis juga menyatakan bahwa skripsi ini tidak mengambil bahan dari publikasi atau tulisan orang lain kecuali yang sudah disebutkan dalam rujukan dan dalam Daftar Pustaka. Penulis bersedia menerima sanksi jika terbukti melakukan plagiasi/penjiplakan. Semarang, Desember 2017 Penulis, Afinda Rosa Husnia NIM 13050113130116 ii iii iv MOTTO DAN PERSEMBAHAN Motto: “The more you give, the more you get.” ~Christie Brinkley “The less you give a damn, the happier you will be.” ~Anonymous “There is no next life. Life should be messy.” ~Park Myungsoo “I don’t have a dream. I just want to chill.” ~Park Myungsoo Persembahan: Untuk kedua Orangtua yang saya cintai serta adik dan kakak yang selalu memberi semangat dan pengertian. -

A Multi-Dimensional Study of the Emotion in Current Japanese Popular Music

Acoust. Sci. & Tech. 34, 3 (2013) #2013 The Acoustical Society of Japan PAPER A multi-dimensional study of the emotion in current Japanese popular music Ryo Yonedaà and Masashi Yamada Graduate School of Engineering, Kanazawa Institute of Technology, 7–1 Ohgigaoka, Nonoich, 921–8501 Japan ( Received 22 March 2012, Accepted for publication 5 September 2012 ) Abstract: Musical psychologists illustrated musical emotion with various numbers of dimensions ranging from two to eight. Most of them concentrated on classical music. Only a few researchers studied emotion in popular music, but the number of pieces they used was very small. In the present study, perceptual experiments were conducted using large sets of popular pieces. In Experiment 1, ten listeners rated musical emotion for 50 J-POP pieces using 17 SD scales. The results of factor analysis showed that the emotional space was constructed by three factors, ‘‘evaluation,’’ ‘‘potency’’ and ‘‘activity.’’ In Experiment 2, three musicians and eight non-musicians rated musical emotion for 169 popular pieces. The set of pieces included not only J-POP tunes but also Enka and western popular tunes. The listeners also rated the suitability for several listening situations. The results of factor analysis showed that the emotional space for the 169 pieces was spanned by the three factors, ‘‘evaluation,’’ ‘‘potency’’ and ‘‘activity,’’ again. The results of multiple-regression analyses suggested that the listeners like to listen to a ‘‘beautiful’’ tune with their lovers and a ‘‘powerful’’ and ‘‘active’’ tune in a situation where people were around them. Keywords: Musical emotion, Popular music, J-POP, Semantic differential method, Factor analysis PACS number: 43.75.Cd [doi:10.1250/ast.34.166] ‘‘activity’’ [3]. -

Lista De Música 10.165 Canções

LISTA DE MÚSICA 10.165 CANÇÕES INTÉRPRETE CÓDIGO TÍTULO INÍCIO DA LETRA IDIOMA 19 18483 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA WATTE Genki desu ka kimi wa ima mo JAP 365 6549 SÃO PAULO Tem dias que eu digo não invento no meu BRA 10cc 4920 I'M NOT IN LOVE I'm not in love so don't forget it EUA 14 Bis 3755 LINDA JUVENTUDE Zabelê, zumbi, besouro vespa fabricando BRA 14 Bis 6074 PLANETA SONHO Aqui ninguém mais ficará depois do sol BRA 14 Bis 6197 TODO AZUL DO MAR Foi assim como ver o mar a primeira vez que BRA 14 Bis 7392 NATURAL Penso em você no seu jeito de falar BRA 14 Bis 7693 ROMANCE Flores simples enfeitando a mesa do café BRA 14 Bis 9556 UMA VELHA CANÇÃO ROCK'N'ROLL Olhe oh oh oh venha solte seu corpo no mundo BRA 14 Bis 1039 BOLA DE MEIA BOLA DE GUDE Há um menino há um moleque BRA 3 Doors Down 9033 HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older EUA 4 Non Blondes 9072 WHAT'S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still EUA 4 Non Blondes 2578 SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down EUA 5 a Seco - Maria Gadú 15225 EM PAZ Caiu do céu se revelou anjo da noite e das manhãs BRA 5th Dimension (The) 9092 AQUARIUS When the moon is in the seventh house and EUA A Banda Mais Bonita da Cidade 2748 ORAÇÃO Meu amor essa é a última oração BRA A Banda Mais Bonita da Cidade 15450 CANÇÃO PRA NÃO VOLTAR Não volte pra casa meu amor que aqui é BRA A Cor do Som 6402 ABRI A PORTA Abri a porta apareci a mais bonita sorriu pra BRA A Cor do Som 7175 MENINO DEUS Menino Deus um corpo azul-dourado BRA A Cor do Som 7480 ZANZIBAR No azul de Jezebel no céu de Calcutá BRA A Cor do -

Amazing Grace with Minako Honda Traditional Japanese Lyrics: Tokiko Iwatani

Hayley Sings Japanese Songs Amazing Grace With Minako Honda Traditional Japanese Lyrics: Tokiko Iwatani Hayley Amazing grace, how sweet the sound That saved a wretch like me I once was lost, but now am found Was blind, but now I see やさしい愛の てのひらで (Yasashii ai no tenohira de) 今日もわたしは うたおう (Kyō mo watashi wa utaou) 何も知らずに 生きてきた (Nani mo shirazu ni Ikite kita) わたしは もう迷わない (Watashi wa mō mayowanai) Minako ひかり輝く 幸せを (Hikari kagayaku shiawase wo) 与えたもうた あなた (Ataeta mo uta anata) おおきなみむねに ゆだねましょう (Ōkina mi mune ni yudanemashou) 続く世界の 平和を (Tsuzuku sekai no heiwa wo) Together Amazing grace, how sweet the sound That saved a wretch like me I once was lost, but now am found Was blind, but now I see Hayley Sings Japanese Songs Hana Music & Lyrics: Shoukichi Kina English Lyric: Reiko Yukawa Additional Lyric: Hayley Westenra I see the river in the daylight Glistening as it flows its way I see the people travelling Through the night and through the day I see their paths colliding Water drops and golden ray Flowers bloom, oh, flowers bloom On this blessed day Let the tears fall down Let the laughter through One day, oh, one day The flowers will reach full bloom I see your tears in the daylight Glistening as they fall from you I see your love escaping Flowing free and flowing true I want to make these rivers Into something shining new Let me make these flowers bloom Let me make them bloom for you Let the tears fall down Let the laughter through One day, oh, one day The flowers will reach full bloom I want to take you to the river Down to where the flowers -

Of芭蕉俳句 Bashô's Haiku

1655 まことの華見:REAL SPLENDOUR OF 風雅“FÛGA” OF芭蕉俳句 BASHÔ’S HAIKU TAKACHI, Jun’ichiro JAPONYA/JAPAN/ЯПОНИЯ MASAOKA Shiki正岡子規, a renovator of HAIKU in Meiji Era, noticed a significance in Herbert Spenser’s “On Style” which indicated the poetics ― the capability to express “the whole” by means of a “minor image” ―, and came to assert that “Haiku” can express a high psychic idea by “opening eyes of insight through devotion to Zen,” that is, “seeing and listening into the wind and the light in objective scapes.”(108-9) By him, the good haiku of BASHÔ are 200 or less out of the whole 1000. Meanwhile, the dilettante of Japanese literature, R. H. Blyth, following Lafcadio Hearne, has translated BASHÔ, ISSA and others in the history of haiku, 1962, and asserted that “Haiku” is “Nature poetry” which stands on “animism, Zen, the sky, and over-purification without beauty,” to restrict only 100 haikus out of the whole 2000 as fine. (8, 12) By TAKACHI’s count, BASHÔ’s whole work of Hokku 発句 are 920 in all, and fine Haiku-grams are about 60. Ezra Pound in late Imagist age regarded Japanese Haiku as “Nature poem” in “On Vorticism,” 1914. But, before that, he declared the famous formulas of definition by the “Super-position” poetics, “the one image poem is a form of super-position ; that is to say, it is one idea set on top of another [idea = image]” ― that Haiku is “Image poem.” It is true that Haiku-art consists of the “Super- position” to propose the inner meaning, “Idea,” by the external figure or scape, “Image.” It is exactly the same Haiku-poetics as BASHÔ’s principle that he stated in the preface of oi-no-kobumi 『笈の小文』(Travel Notes in Knapsack) ― “To See「見ること」is nothing but Flower「花」. -

Musicas Do Serial Z0E7D2CS

VIDEOKÊ GUARULHOS 9.899 CANÇÕES FONE: 11-2440-3717 LISTA DE MÚSICAS CANTOR CÓDIGO MÚSICA INICIO DA LETRA IDIOMA 10000 Maniacs 19807 MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time BRA 10cc 4920 I'M NOT IN LOVE I'm not in love so don't forget it EUA 14 Bis 3755 LINDA JUVENTUDE Zabelê, zumbi, besouro vespa fabricando BRA 14 Bis 7392 NATURAL Penso em você no seu jeito de BRA 14 Bis 6074 PLANETA SONHO Aqui ninguém mais ficará de... BRA 14 Bis 7693 ROMANCE Flores simples enfeitando a mesa do café BRA 14 Bis 6197 TODO AZUL DO MAR Foi assim como ver o mar a ... BRA 14 Bis 9556 UMA VELHA CANÇÃO ROCK'N'ROLL Olhe oh oh oh venha solte seu corpo no mundo BRA 19 18483 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA WATTE Genki desu ka kimi wa ima mo JAP 365 6549 SÃO PAULO Tem dias que eu digo não invento no meu BRA 3 Doors Down 9033 HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older EUA 4 Non Blondes 2578 SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down EUA 4 Non Blondes 9072 WHAT'S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still EUA 5 a Seco - Maria Gadú 15225 EM PAZ Caiu do céu se revelou anjo da noite e das manhãs BRA 5 Seconds Of Summer 19852 SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT He-ey e-hey... Simmer down simmer down EUA 5th Dimension (The) 9092 AQUARIUS When the moon is in the seventh house and EUA A Banda Mais Bonita da Cidade 15450 CANÇÃO PRA NÃO VOLTAR Não volte pra casa meu amor que aqui é BRA A Banda Mais Bonita da Cidade 2748 ORAÇÃO Meu amor essa é a última oração BRA Abba 4877 CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what's wrong you're EUA Abba 4574 DANCING QUEEN Yeh! you can dance you can jive EUA Abba 19333 FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando EUA Abba 9116 I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing EUA Abba 19768 KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU No more carefree laughter EUA Abba 2533 MAMMA MIA I've been cheated by you since I don't EUA Abba 4787 THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL I don't wanna talk EUA Abelhudos 1804 AS CRIANÇAS E OS ANIMAIS Ê ô ê ô...P de pato G de .. -

![Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1957/fairy-inc-sheet-music-products-list-last-updated-2013-03-018-price-japanese-yen-a-525-b-788-c-683-4041957.webp)

Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683

Fairy inc. Sheet Music Products list Last updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) A \525 B \788 C \683 ST : Standard Version , OD : On Demand Version , OD-PS : Piano solo , OD-PV : Piano & Vocal , OD-GS : Guitar solo , OD-GV : Guitar & Vocal A Band Score Piano Guitar Title Artist Tie-up ST OD ST OD-PS OD-PV ST OD-GS OD-GV A I SHI TE RU no Sign~Watashitachi no Shochiku Distributed film "Mirai Yosouzu ~A I DREAMS COME TRUE A A A Mirai Yosouzu~ SHI TE RU no Sign~" Theme song OLIVIA a little pain - B A A A A inspi'REIRA(TRAPNEST) A Song For James ELLEGARDEN From the album "BRING YOUR BOARD!!" B a walk in the park Amuro Namie - A a Wish to the Moon Joe Hisaishi - A A~Yokatta Hana*Hana - A A Aa Superfly 13th Single A A A Aa Hatsu Koi 3B LAB.☆ - B Aa, Seishun no Hibi Yuzu - B Abakareta Sekai thee michelle gun elephant - B Abayo Courreges tact, BABY... Kishidan - B abnormalize Rin Toshite Shigure Anime"PSYCHO-PASS" Opening theme B B Acro no Oka Dir en grey - B Acropolis ELLEGARDEN From the album "ELEVEN FIRE CRACKERS" B Addicted ELLEGARDEN From the album "Pepperoni Quattro" B ASIAN KUNG-FU After Dark - B GENERATION again YUI Anime "Fullmetal Alchemist" Opening theme A B A A A A A A Again 2 Yuzu - B again×again miwa From 2nd album "guitarium" B B Ageha Cho PornoGraffitti - B Ai desita. Kan Jani Eight TBS Thursday drama 9 "Papadoru!" Theme song B B A A A Ai ga Yobu Hou e PornoGraffitti - B A A Ai Nanda V6 - A Ai no Ai no Hoshi the brilliant green - B Ai no Bakudan B'z - B Ai no Kisetsu Angela Aki NHK TV novel series "Tsubasa" Theme song A A -

140625Karaoke Performer.Pdf

ICC留学生カラオケ・コンテスト ~世界のワセダ、歌でつながるコミュニティ~ ザ・ファイナル ICC International Student Karaoke Contest -Bringing the Waseda Community Together Through Song- [Grand Final] ♫ ファイナリスト / Finalists ♫ Entry Group Name / Yea Country Photo School Song Artist Message No. Name r* /Region 楽しそうに見える日本の生活では、だれでも知らない苦しいこと や悔しいことがたくさんあります。自分が決めた道をあきらめたい 社学 遥か 時、この曲を聞いて、自分を支えた人を思い出せば、「必ず夢を 1 YUTONG ZHOU 3 China GReeeeN School of Social Sciences Haruka 叶えて帰る」気持ちが強くなります。出場順番が1ですが、投票 する際、私のことを忘れないでね!最後の結果も1位になれる ように頑張りたいと思います! “ Precious” talks about a young lady who was skeptical about love, but later summoned the courage to make her relationship work. Sometimes 国際教養 伊藤由奈 2 OH Xuemin 4 Singapore Precious life seems hard, but have faith, and things will work SILS Yuna Ito out in the end. I first sang this song at a dear friend’s wedding. This time, I would like to dedicate this song to a special someone. 政経 School of Political 母から子への暖かな想いや包容力を意識しながら歌います。母 World Englishes 国にいる親への想いを添えて「百年続きますように」の歌詞のよう Science and Economics Korea ハナミズキ 一青窈 3 (Seongyeon Kim & 4 に、遠くにいても両者の愛情は相変わらず永遠に続くというのを 文 School of Humanities Japan Hanamizuki Yo Hitoto 松下結妃) 想いながら。一番のポイントはロングトーンに支えられた感性的 and Social Sciences な歌声と、ビブラートなど装飾を加えた歌声のハーモニーです。 さくらは美しい花です。私が初めて日本に来た時は4年前の冬で 創造理工 した。雪に覆われた枯れるたくさんのさくらの木を見た時、次の春 桜 コブクロ 4 楊 嘉胤 School of Creative Science 2 China にどのような風景になるかなと思いました。高校を卒業して別れ Sakura Kobukuro and Engineering た友達に対する思いを「さくら」の歌でみなさんに伝えたいと思い ます。 There are a lot of Japanese songs that I like, but they are mostly rock and Visual Kei songs sang by guys, アジ太 thus I cannot sing them. So I chose this rock track by GLAMOROUS NANA starring 5 Fabiani Diletta Grad School of Asia Pacific ND Italy Mika Nakashima, written by Hyde of L'Arc-en-Ciel for SKY MIKA NAKASHIMA Studies a woman's voice. -

Universitas Kristen Maranatha Xviii LAMPIRAN 1 LAGU-LAGU

LAMPIRAN 1 LAGU-LAGU NAKASHIMA MIKA 雪雪雪の雪ののの華華華華 のびた人陰を 舗道に並べ 夕闇のなかをキミと歩いてる 手を繋いでいつまでもずっと そばにいれたなら泣けちゅうくらい 風が冷たくなって 冬の匂いがした そろそろこの街に キミと近付ける季節がくる 今年、最初の雪の華を 2人寄り添って 眺めているこの時間に シアワセがあふれだす 甘えとか弱さじゃない ただ、キミを愛してる 心からそう思った キミがいると どんなことでも 乗りきれるような気持ちになってる こんな日々がいつまでもきっと 続いてくことを祈っているよ 風が窓を揺らした 夜は揺り起こして どんな悲しいことも ボクが笑顔へと変えてあげる 舞い落ちてきた雪の華が 窓の外ずっと 降りやむことをしらずに ボクらの街を染める 誰かのために何かを したいと思えるのが xviii Universitas Kristen Maranatha 愛ということを知った もし、キミを失ったとしたなら 星になってキミを照らすだろう 笑顔も 涙に濡れてる夜も いつもいつでもそばにいるよ 今年、最初の雪の華を 2人寄り添って 眺めているこの時間に シアワセがあふれだす 甘えとか弱さじゃない ただ、キミとずっと このまま一緒にいたい 素直にそう思える この街に降り積もってく 真っ白な雪の華 2人の胸にそっと思い出を描くよ これからもキミとずっと… (中島。実嘉;BEST album ;2005) Nobita kage wo hodou ni narabe Yuuyami no naka wo kimi to aruiteru Te wo tsunaide itsumademo zutto Soba ni ireta nara nakechaukurai Kaze ga tsumetaku natte Fuyu no nioi ga shita Sorosoro kono machi ni Kimi to chikatzukeru kisetsu ga kuru Kotoshi saisho no yuki no hana wo Futari yori sotte Nagameteiru kono toki ni Shiawase ga afuredasu Amae toka yowasa janai Tada, kimi wo aishiteru Kokoro kara sou omotta Kimi ga iru to donna koto demo Norikireru you na kimochi ni natteru Donna hibi ga itsumademo kitto Tsuzuiteku koto wo inotteiruyo xix Universitas Kristen Maranatha Kaze ga mado wo yurashita Yoru wo yuri okoshite Donna kanashii koto mo Boku ga egao e to kaete ageru Mai ochitekita yuki no hana ga Mado no sotto zutto Furiyamu koto wo shirazu ni Bokura no machi wo someru Dareka no tame ni nanika wo Shitai to omoeru no ga Ai to iu koto wo shitta Moshi, kimi wo ushinatta toshita nara Hoshi ni natte kimi wo terasu -

Basho's Haikus

Basho¯’s Haiku Basho¯’s Haiku Selected Poems by Matsuo Basho¯ Matsuo Basho¯ Translated by, annotated, and with an Introduction by David Landis Barnhill STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Matsuo Basho¯, 1644–1694. [Poems. English. Selections] Basho¯’s haiku : selected poems by Matsuo Basho¯ / translated by David Landis Barnhill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6165-3 — 0-7914-6166-1 1. Haiku—Translations into English. 2. Japanese poetry—Edo period, 1600–1868—Translations into English. I. Barnhill, David Landis. II. Title. PL794.4.A227 2004 891.6’132—dc22 2004005954 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 for Phyllis Jean Schuit spruce fir trail up through endless mist into White Pass sky Contents Preface ix Selected Chronology of the Life of Matsuo Basho¯ xi Introduction: The Haiku Poetry of Matsuo Basho¯ 1 Translation of the Hokku 19 Notes 155 Major Nature Images in Basho¯’s Hokku 269 Glossary 279 Bibliography 283 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Translation 287 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Japanese 311 Index of Names 329 vii Preface “You know, Basho¯ is almost too appealing.” I remember this remark, made quietly, offhand, during a graduate seminar on haiku poetry. -

Intérprete Título Codigo Pacote Créditos 19 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA18483 WATTE JP7D 16 A.I

www.KaraokeCenter.com.br Intérprete Título Codigo Pacote Créditos 19 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA18483 WATTE JP7D 16 A.I. STORY 2017 JP4A 12 Abe Shizue MIZU IRO NO TEGAMI 18424 JP7B 16 Ai BELIEVE 18486 JP7D 16 Ai YOU ARE MY STAR 18319 JP6C 16 Ai Johji & Shima ChinamiAKAI GLASS 5103 JP1 8 Ai Takano ORE GA SEIGI DA! JASPION 18627 JP8C 20 Aikawa Nanase BYE BYE 5678 JP3 11 Aikawa Nanase SWEET EMOTION 5815 JP3 11 Aikawa Nanase YUME MIRU SHOJYO JYA IRARENAI5645 JP2 11 Aiko KABUTO MUSHI 2031 JP4A 12 AKB48 365 NICHI NO KAMI HIKOHKI 18601 JP8C 20 Akikawa Masafumi SEN NO KAZE NI NATTE 2015 JP4A 12 Akimoto Junko AI KAGI 18602 JP8C 20 Akimoto Junko AI NO MAMA DE... 2022 JP4A 12 Akimoto Junko AME NO TABIBITO 2124 JP4D 12 Akimoto Junko MADINSON GUN NO KOI 2011 JP4A 12 Akimoto Junko TASOGARE LOVE AGAIN 18233 JP6A 12 Akioka Shuji AIBOH ZAKE 18562 JP8B 16 Akioka Shuji OTOKO NO TABIJI 2296 JP5C 12 Akioka Shuji SAKE BOJO 18432 JP7B 16 Alan BALLAD ~NAMONAKI KOI NO UTA~18485 JP7D 16 Alan KUON NO KAWA 18580 JP8B 16 Alice FUYU NO INAZUMA 5117 JP1 8 Alice IMA WA MOH DARE MO 2266 JP5B 12 Amane Kaoru TAIYOH NO UTA 18279 JP6B 12 Ami Suzuki ALONE IN MY ROOM 5658 JP3 11 Amin MATSU WA 2223 JP5A 12 Amuro Namie CAN YOU CELEBRATE 5340 JP2 11 Amuro Namie CHASE THE CHANCE 5341 JP2 11 Amuro Namie FIGHT TOGETHER 18536 JP8A 16 Amuro Namie HERO 18620 JP8C 20 Amuro Namie I HAVE NEVER SEEN 5711 JP3 11 Amuro Namie NEVER END 5766 JP3 11 Amuro Namie SAY THE WORD 5798 JP3 11 Amuro Namie STOP THE MUSIC 5294 JP1 8 Amuro Namie THINK OF ME 5820 JP3 11 Amuro Namie TRY ME (WATASHI O SHINDITE)5300 -

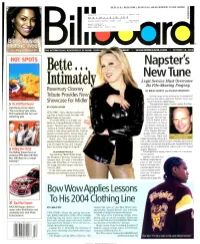

Bette... New Tune R Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 3 -DIGIT 908 #BCNCCVR * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** 111I111I111I1111I1H 1I111I11I111I111III111111II111I1 u A06 80101 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 508 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Black Music' Historic Wee See Pages 20 and 58 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO A MENT www.billboard.com OCTOBER 18, 2003 HOT SPOTS Napster's Bette... New Tune r Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny Rosemary Clooney BY BRIAN GARRITY and JULIANA KORANTENG Tribute Provides New On the verge of resurfacing as a commercial service, the once -notorious Napster must face Showcase For Midler its own double -edged legacy. 5 The DVD That Roared The legitimate digital music market that Nap - helped force into Walt Disney Home Video's BY CHUCK TAYLOR ster existence is poised "The Lion Kng" gets deluxe NEW YORK -Barry Manilow recalls wak- to go mainstream in DVD treatment and two -year ing from a dream earlier this year with North America and plan. marketing Bette Midler on his mind. Europe. Yet the maj- "It was the 1950s in my dream, and ority of digital music Bette wa: singing Rosemary Clooney consumers in those songs," Manilow says with a smile. territories continue to "Bette and I hadn't spoken in years, but I get their music for free picked u- the phone and told her I had an from Napster -like peer- i idea for a tribute album. I knew there was to -peer (P2P) networks. absolutely no one else who could do this." In Europe, legal and GOROG: GIVING CONSUMERS WHATTHEY WANT Midle- says, "The concept was ab- illegal downloads are on the solutely billiant.