Trends in the Exchange of Co2 and Ch4 Between the Atmosphere and Eastern Canadian Subarctic and Arctic Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reduced Net Methane Emissions Due to Microbial Methane Oxidation in a Warmer Arctic

LETTERS https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0734-z Reduced net methane emissions due to microbial methane oxidation in a warmer Arctic Youmi Oh 1, Qianlai Zhuang 1,2,3 ✉ , Licheng Liu1, Lisa R. Welp 1,2, Maggie C. Y. Lau4,9, Tullis C. Onstott4, David Medvigy 5, Lori Bruhwiler6, Edward J. Dlugokencky6, Gustaf Hugelius 7, Ludovica D’Imperio8 and Bo Elberling 8 Methane emissions from organic-rich soils in the Arctic have bacteria (methanotrophs) and the remainder is mostly emitted into been extensively studied due to their potential to increase the atmosphere (Fig. 1a). The methanotrophs in these wet organic the atmospheric methane burden as permafrost thaws1–3. soils may be low-affinity methanotrophs (LAMs) that require However, this methane source might have been overestimated >600 ppm of methane (by moles) for their growth and mainte- without considering high-affinity methanotrophs (HAMs; nance23. But in dry mineral soils, the dominant methanotrophs are methane-oxidizing bacteria) recently identified in Arctic min- high-affinity methanotrophs (HAMs), which can survive and grow 4–7 eral soils . Herein we find that integrating the dynamics of at a level of atmospheric methane abundance ([CH4]atm) of about HAMs and methanogens into a biogeochemistry model8–10 1.8 ppm (Fig. 1b)24. that includes permafrost soil organic carbon dynamics3 leads Quantification of the previously underestimated HAM-driven −1 to the upland methane sink doubling (~5.5 Tg CH4 yr ) north of methane sink is needed to improve our understanding of Arctic 50 °N in simulations from 2000–2016. The increase is equiva- methane budgets. -

Is Rapid Climate Change in the Arctic a Planetary Emergency? Peter Carter, November 2013 Updated 2019

Is Rapid Climate Change in the Arctic a Planetary Emergency? Peter Carter, November 2013 updated 2019. Introduction This paper presents a compelling case, supported by the climate change research, that the combination of: • global inaction on greenhouse gas emissions, • climate system inertias, and • multiple enormous Arctic sources of amplifying feedbacks (covered in this paper) constitutes an extreme-risk planetary emergency, for the survival of civilization, the human race and most life Research on climate change and the Arctic shows that we face a catastrophic risk of uncontrollable, accelerating global warming due to several amplifying feedbacks from enormous feedback sources in the Arctic. These include the Arctic snow/ice-albedo feedback and greenhouse gas feedbacks (methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide). Under global warming, the Arctic is changing far faster than other regions of Earth. Numerous – and extremely large – Arctic sources of amplifying feedbacks are already responding (have been triggered in response) to rapid Arctic warming. These Arctic feedbacks, if not addressed in time (now) and with the appropriate degree of mitigation, can only be expected to accelerate the rate of global warming. They constitute a very large risk of planetary catastrophic consequences, including Arctic greenhouse gas feedback so-called "runaway" chaotic climate disruption / runaway global heating/ hot house Earth. This paper describes global warming positive feedbacks already operant in the Arctic, and explains the large risk of planetary -

Working Towards a Just Peace in the Middle East

KAIROS Policy Briefing Papers are written to help inform public debate on key domestic and foreign policy issues No. 41 April 2015 Hopeful Signs, Alarming Realities on the Road to Climate Justice By John Dillon Ecological Economy Program Coordinator “Climate change for us is a matter of life or death.”1 waiting for the Paris conference to make decisions These stark words were spoken by Rev. Tafue Lu- that, in most cases, will take effect only in 2020. sama, General Secretary of the Tuvalu Christian Church, in September 2014 at an interfaith summit in New York. How prophetic they were in March 2015 when Super Cyclone Pam wreaked havoc on the Pa- cific island state, killing dozens and destroying thou- sands of homes in neighbouring Vanuatu. Rising sea levels and warmer water temperatures have increased the frequency and intensity of tropical storms like this one and Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philip- pines in 2013. Yet, although climate change is already devastating the lives of millions of vulnerable people, Rev. Olav Cyclone Pam survivors survey damage in Vanuatu. Tveit, General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, reminds us: “Despite all the negative condi- Hopeful signs include initiatives being undertaken tions, we have the right to hope, not as a passive wait- by some Canadian provinces such as putting a price ing but as an active process towards justice and on carbon emissions and declaring moratoria on hy- peace.”2 This Briefing Paper examines some hopeful draulic fracturing (fracking) to extract shale gas. As signs of progress in the struggle for climate justice, well, a number of civil society groups, such as Cli- despite major obstacles. -

Thaw Pond Development and Initial Vegetation Succession in Experimental Plots at a Siberian Lowland Tundra Site

Plant Soil (2017) 420:147–162 DOI 10.1007/s11104-017-3369-8 REGULAR ARTICLE Thaw pond development and initial vegetation succession in experimental plots at a Siberian lowland tundra site Bingxi Li & Monique M. P. D. Heijmans & Daan Blok & Peng Wang & Sergey V. Karsanaev & Trofim C. Maximov & Jacobus van Huissteden & Frank Berendse Received: 15 March 2017 /Accepted: 3 August 2017 /Published online: 22 August 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Methods In the experiment, we measured changes in Background and aims Permafrost degradation has the soil thaw depth, plant species cover and soil subsidence potential to change the Arctic tundra landscape. We over nine years (2007–2015). observed rapid local thawing of ice-rich permafrost Results After abrupt initial thaw, soil subsidence in the resulting in thaw pond formation, which was triggered removal plots continued indicating further thawing of − by removal of the shrub cover in a field experiment. permafrost albeit at a much slower pace: 1 cm y 1 over − This study aimed to examine the rate of permafrost thaw 2012–2015 vs. 5 cm y 1 over 2007–2012. Grass cover and the initial vegetation succession after the permafrost strongly increased after the initial shrub removal, but collapse. later declined with ponding of water in the subsiding removal plots. Sedges established and expanded in the wetter removal plots. Thereby, the removal plots have Responsible Editor: Zucong Cai. become increasingly similar to nearby ‘natural’ thaw Electronic supplementary material The online version of this ponds. article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3369-8)contains Conclusions The nine years of field observations in a supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. -

FIRST-ORDER DRAFT IPCC WGII AR5 Chapter 19 Do Not Cite, Quote

FIRST-ORDER DRAFT IPCC WGII AR5 Chapter 19 1 Chapter 19. Emergent Risks and Key Vulnerabilities 2 3 Coordinating Lead Authors 4 Michael Oppenheimer (USA), Maximiliano Campos (Costa Rica) 5 6 Lead Authors 7 Joern Birkmann (Germany), George Luber (USA), Brian O’Neill (USA), Kiyoshi Takahashi (Japan), Rachel Warren 8 (UK) 9 10 Contributing Authors 11 Franz Berkhout (Netherlands), Pauline Dube (Botswana), Wendy Foden (South Africa), Stefan Greiving (Germany), 12 Solomon Hsiang (USA), Klaus Keller (USA), Joan Kleypas (USA), Robert Kopp (USA), Carlos Peres (UK), Jeff 13 Price (UK), Alan Robock (USA), Wolfram Schlenker (USA), Richard Tol (UK) 14 15 Review Editors 16 Mike Brklacich (Canada), Sergey Semenov (Russian Federation) 17 18 Chapter Scientist 19 Solomon Hsiang (USA) 20 21 22 Contents 23 24 Executive Summary 25 26 19.1. Purpose, Scope, and Structure of the Chapter 27 19.1.1. Historical Development of this Chapter 28 19.1.2. The Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate 29 Change Adaptation (SREX) 30 19.1.3. New Developments in this Chapter 31 32 19.2. Framework for Identifying Key Vulnerabilities, Key Risks, and Emergent Risks 33 19.2.1. Risk and Vulnerability 34 19.2.2. Criteria for Identifying Key Vulnerabilities and Key Risks 35 19.2.2.1. Criteria for Identifying Key Vulnerabilities 36 19.2.2.2. Criteria for Identifying Key Risks 37 19.2.3. Criteria for Identifying Emergent Risks 38 19.2.4. Identifying Key and Emergent Risks under Alternative Development Pathways 39 19.2.5. Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Emergent Risks 40 41 19.3. -

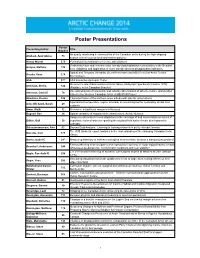

Poster Presentations

Poster Presentations Poster Presenting Author Title Number Air quality monitoring in communities of the Canadian arctic during the high shipping Aliabadi, Amir Abbas 73 season with a focus on local and marine pollution Allard, Michel 376 Permafrost International conference advertisment Vertical structure and environmental forcing of phytoplankton communities in the Beaufort Ardyna, Mathieu 139 Sea: Validation and application of novel satellite-derived phytoplankton indicators Spatial and Temporal Variability of Leaf Area Index and NDVI in a Sub-Arctic Tundra Arruda, Sean 279 Environment ASA 377 ASA Interactive Outreach Poster Occurrence and characteristics of Arctic Skate, Amblyraja hyperborea (Collette 1879) Atchison, Sheila 122 (Rajidae), in the Canadian Beaufort Use and analysis of community and industry observations of adverse marine and weather Atkinson, David E 76 states in the Western Canadian Arctic: A MEOPAR Project Atlaskina, Ksenia 346 Characterization of the northern snow albedo with satellite observations A permafrost temperature regime simulator as a learning tool for secondary school Inuit Aubé-Michaud, Sarah 29 students Awan, Malik 12 Wolverine: a traditional resource in Nunavut Bagnall, Ben 26 Spatial variability of hazard risk to infrastructure, Arviat, Nunavut Using a media scan to reveal disparities in the coverage of and conversation on issues of Baikie, Gail 38 importance to local women regarding the muskrat falls hydro-electric development in Labrador Balasubramaniam, Ann 62 Beyond Data Analysis: Learning to framing -

Stolerov Arctic Meth

Critical Review pubs.acs.org/est Review of Methane Mitigation Technologies with Application to Rapid Release of Methane from the Arctic Joshuah K. Stolaroff,* Subarna Bhattacharyya, Clara A. Smith, William L. Bourcier, Philip J. Cameron-Smith, and Roger D. Aines Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Methane is the most important greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide, with particular influence on near-term climate change. It poses increasing risk in the future from both direct anthropogenic sources and potential rapid release from the Arctic. A range of mitigation (emissions control) technologies have been developed for anthropogenic sources that can be developed for further application, including to Arctic sources. Significant gaps in understanding remain of the mechanisms, magnitude, and likelihood of rapid methane release from the Arctic. Methane may be released by several pathways, including lakes, wetlands, and oceans, and may be either uniform over large areas or concentrated in patches. Across Arctic sources, bubbles originating in the sediment are the most important mechanism for methane to reach the atmosphere. Most known technologies operate on confined gas streams of 0.1% methane or more, and may be applicable to limited Arctic sources where methane is concentrated in pockets. However, some mitigation strategies developed for rice paddies and agricultural soils are promising for Arctic wetlands and thawing permafrost. Other mitigation strategies specific to the Arctic have been proposed but have yet to be studied. Overall, we identify four avenues of research and development that can serve the dual purposes of addressing current methane sources and potential Arctic sources: (1) methane release detection and quantification, (2) mitigation units for small and remote methane streams, (3) mitigation methods for dilute (<1000 ppm) methane streams, and (4) understanding methanotroph and methanogen ecology. -

Phylogeography and Historical Demographics of Lepus Arcticus, L

Molecular Ecology (2005) 14, 3005–3016 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02625.x HaresBlackwell Publishing, Ltd. on ice: phylogeography and historical demographics of Lepus arcticus, L. othus, and L. timidus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha) ERIC WALTARI* and JOSEPH A. COOK† *Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209-8007, USA, †Museum of Southwestern Biology & Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA Abstract Phylogeographical investigations of arctic organisms provide spatial and temporal frameworks for interpreting the role of climate change on biotic diversity in high-latitude ecosystems. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted on 473 base pairs of the mitochondrial control region in 192 arctic hares (Lepus arcticus, Lepus othus, Lepus timidus) and two individual Lepus townsendii. The three arctic hare species are closely related. All L. othus indi- viduals form one well-supported clade, L. arcticus individuals form two well-supported clades, and L. timidus individuals are scattered throughout the phylogeny. Arctic hare distribution was altered dramatically following post-Pleistocene recession of continental ice sheets. We tested for genetic signatures of population expansion for hare populations now found in deglaci- ated areas. Historical demographic estimates for 12 arctic hare populations from throughout their range indicate that L. arcticus and L. othus persisted in two separate North American arctic refugia (Beringia and High Canadian Arctic) during glacial advances of the Pleistocene, while the high genetic diversity in L. timidus likely reflects multiple Eurasian refugia. Keywords: Arctic, Beringia, Lepus, phylogenetics, phylogeography, refugia Received 30 January 2005; revision accepted 20 April 2005 processes affecting species’ history (Edwards & Beerli 2000; Introduction Knowles 2004). -

Ancient DNA Supports Southern Survival of Richardsons Collared Lemming (Dicrostonyx Richardsoni) During the Last Glacial Maximum

Molecular Ecology (2013) 22, 2540–2548 doi: 10.1111/mec.12267 Ancient DNA supports southern survival of Richardson’s collared lemming (Dicrostonyx richardsoni) during the last glacial maximum TARA L. FULTON,*1 RYAN W. NORRIS,*2 RUSSELL W. GRAHAM,† HOLMES A. SEMKEN JR‡ and BETH SHAPIRO*1 *Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, †Department of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, ‡Department of Geoscience, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA Abstract Collared lemmings (genus Dicrostonyx) are circumpolar Arctic arvicoline rodents asso- ciated with tundra. However, during the last glacial maximum (LGM), Dicrostonyx lived along the southern ice margin of the Laurentide ice sheet in communities com- prising both temperate and boreal species. To better understand these communities and the fate of these southern individuals, we compare mitochondrial cytochrome b sequence data from three LGM-age Dicrostonyx fossils from south of the Laurentide ice sheet to sequences from modern Dicrostonyx sampled from across their present-day range. We test whether the Dicrostonyx populations from LGM-age continental USA became extinct at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition ~11000 years ago or, alterna- tively, if they belong to an extant species whose habitat preferences can be used to infer the palaeoclimate along the glacial margin. Our results indicate that LGM-age Dicrostonyx from Iowa and South Dakota belong to Dicrostonyx richardsoni, which currently lives in a temperate tundra environment west of Hudson Bay, Canada. This suggests a palaeoclimate south of the Laurentide ice sheet that contains elements simi- lar to the more temperate shrub tundra characteristic of extant D. -

Climatic Impact of Arctic Ocean Methane Hydrate Dissociation in The

Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-2017-110 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Syst. Dynam. Discussion started: 18 December 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC BY 4.0 License. Climatic impact of Arctic Ocean methane hydrate dissociation in the 21st-century Sunil Vadakkepuliyambatta1*, Ragnhild B Skeie2, Gunnar Myhre2, Stig B Dalsøren2, Anna Silyakova1, Norbert Schmidbauer3, Cathrine Lund Myhre3, Jürgen Mienert1 1CAGE-Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment, and Climate, Department of Geosciences, UiT-The Arctic University of Norway, 9037 Tromsø, Norway. 2CICERO-Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo, PB. 1129 Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway. 3NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research, Instituttveien 18, 2027 Kjeller, Norway. 1 Abstract 2 Greenhouse gas methane trapped in sub-seafloor gas hydrates may play an important role in a 3 potential climate feedback system. The impact of future Arctic Ocean warming on the hydrate 4 stability and its contribution to atmospheric methane concentrations remains an important and 5 unanswered question. Here, we estimate the climate impact of released methane from oceanic 6 gas hydrates in the Arctic to the atmosphere towards the end of the 21st century, integrating 7 hydrate stability and atmospheric modeling. Based on future climate models, we estimate that 8 increasing ocean temperatures over the next 100 years could release up to 17 ± 6 Gt C into the 9 Arctic Ocean. However, the released methane has a limited or minor impact on the global 10 mean surface temperature, contributing only 0.1 % of the projected anthropogenic influenced 11 warming over the 21st century. 12 1. -

Trends in Satellite Earth Observation for Permafrost Related Analyses—A Review

remote sensing Review Trends in Satellite Earth Observation for Permafrost Related Analyses—A Review Marius Philipp 1,2,* , Andreas Dietz 2, Sebastian Buchelt 3 and Claudia Kuenzer 1,2 1 Department of Remote Sensing, Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Wuerzburg, D-97074 Wuerzburg, Germany; [email protected] 2 German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD), German Aerospace Center (DLR), Muenchner Strasse 20, D-82234 Wessling, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Physical Geography, Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Wuerzburg, D-97074 Wuerzburg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change and associated Arctic amplification cause a degradation of permafrost which in turn has major implications for the environment. The potential turnover of frozen ground from a carbon sink to a carbon source, eroding coastlines, landslides, amplified surface deformation and endangerment of human infrastructure are some of the consequences connected with thawing permafrost. Satellite remote sensing is hereby a powerful tool to identify and monitor these features and processes on a spatially explicit, cheap, operational, long-term basis and up to circum-Arctic scale. By filtering after a selection of relevant keywords, a total of 325 articles from 30 international journals published during the last two decades were analyzed based on study location, spatio- temporal resolution of applied remote sensing data, platform, sensor combination and studied environmental focus for a comprehensive overview of past achievements, current efforts, together with future challenges and opportunities. The temporal development of publication frequency, utilized platforms/sensors and the addressed environmental topic is thereby highlighted. -

I ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE, ALASKANS for WILDLIFE

ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE, ALASKANS FOR WILDLIFE, ASSOCIATION OF RETIRED U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE EMPLOYEES, AUDUBON ALASKA, CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY-NATIONAL, CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY-YUKON CHAPTER, CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE, EARTHJUSTICE, ENVIRONMENT AMERICA, EYAK PRESERVATION COUNCIL, FAIRBANKS CLIMATE ACTION COALITION, FRIENDS OF ALASKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGES, GWICH’IN STEERING COMMITTEE, LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS, NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY, NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION, NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE ASSOCIATION, NATIVE MOVEMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL, NATURE CANADA, NORTHERN ALASKA ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER, STAND.EARTH, SIERRA CLUB, THE WILDERNESS SOCIETY, TRUSTEES FOR ALASKA, AND WILDERNESS WATCH March 13, 2019 Submitted via email and online eplanning comment portal Nicole Hayes Attn: Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program EIS 222 West 7th Ave., Stop #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 [email protected] [email protected] Comments re: Notice of Availability of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program and Announcement of Public Subsistence- Related Hearings, 83 Fed. Reg. 67,337 (Dec. 28, 2018). Dear Ms. Hayes, On behalf of the above-listed organizations and our many millions of members and supporters nationwide and internationally, we submit the following comments in response to the public notice from December 28, 2018 Notice of Availability of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program and Announcement of Public Subsistence-Related Hearings, 83 Fed. Reg. 67,337 (Dec. 28, 2018). We oppose all oil and gas activities on the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. We stand with the Gwich’in Nation and support their efforts to protect their human rights and food security by protecting the Coastal Plain.