Before They Were Vikings: Scandinavia and the Franks up to the Death of Louis the Pious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christian Martyr Movement of 850S Córdoba Has Received Considerable Scholarly Attention Over the Decades, Yet the Movement Has Often Been Seen As Anomalous

The Christian martyr movement of 850s Córdoba has received considerable scholarly attention over the decades, yet the movement has often been seen as anomalous. The martyrs’ apologists were responsible for a huge spike in evidence, but analysis of their work has shown that they likely represented a minority “rigorist” position within the Christian community and reacted against the increasing accommodation of many Mozarabic Christians to the realities of Muslim rule. This article seeks to place the apologists, and therefore the martyrs, in a longer-term perspective by demonstrating that martyr memories were cultivated in the city and surrounding region throughout late antiquity, from at least the late fourth century. The Cordoban apologists made active use of this tradition in their presentation of the events of the mid-ninth century. The article closes by suggesting that the martyr movement of the 850s drew strength from churches dedicated to earlier martyrs from the city and that the memories of the martyrs of the mid-ninth century were used to reinforce communal bonds at Córdoba and beyond in the following years. Memories and memorials of martyrdom were thus powerful means of forging connections across time and space in early medieval Iberia. Keywords Hagiography / Iberia, Martyrdom, Mozarabs – hagiography, Violence, Apologetics, Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain – martyrs, Eulogius of Córdoba, martyr, Álvaro de Córdoba, Paulo, author, Visigoths (Iberian kingdom) – hagiography In the year 549, Agila (d. 554), king of the Visigoths, took it upon himself to bring the city of Córdoba under his power. The expedition appears to have been an utter disaster and its failure was attributed by Isidore of Seville (d. -

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs

chapter 6 “Love’s Lament”: Paschasius Radbertus and the Song of Songs The Song of Songs was understood by many Carolingian exegetes as the great- est, highest, and most obscure of Solomon’s three books of wisdom. But these Carolingian exegetes would also have understood the Song as a dialogue, a sung exchange between Christ and his church: in fact, as the quintessential spiritual song. Like the liturgy of the Eucharist and the divine office, the Song of Songs would have served as a window into heavenly realities, offering glimpses of a triumphant, spotless Bride and a resurrected, glorified Bridegroom that ninth- century reformers’ grim views of the church in their day would have found all the more tantalizing. For Paschasius Radbertus, abbot of the great Carolingian monastery of Corbie and as warm and passionate a personality as Alcuin, the Song became more than simply a treasury of imagery. In this chapter, I will be examining Paschasius’s use of the Song of Songs throughout his body of work. Although this is necessarily only a preliminary effort in understanding many of the underlying themes at work in Paschasius’s biblical exegesis, I argue that the Song of Songs played a central, formative role in his exegetical imagina- tion and a structural role in many of his major exegetical works. If Paschasius wrote a Song commentary, it has not survived; nevertheless, the Song of Songs is ubiquitous in the rest of his exegesis, and I would suggest that Paschasius’s love for the Song and its rich imagery formed a prism through which the rest of his work was refracted. -

Boone County Fiscal Court Governmental Funds FY14

Approved (Ord. 13-12) Boone County Fiscal Court Approved (Ord. 13-12) Governmental Funds FY14 Budgeted Expenses 2014 General Fund General Government Judge/Executive 001-5001-101 Salaries-Elected Officials 110,780.00 001-5001-106 Salaries-Office Staff 263,500.00 Total Personnel Services 374,280.00 001-5001-212 HB810 Training Incentive 4,000.00 4,000.00 001-5001-429 Fuel 5,200.00 001-5001-445 Office Materials & Supplies 2,000.00 Total Supplies and Materials 7,200.00 001-5001-551 Memberships 12,000.00 001-5001-565 Printing, Stationary, Forms, Etc. 1,000.00 001-5001-569 Registrations, Conferences, Training, Etc. 11,000.00 001-5001-578 Utilities-General 3,500.00 001-5001-585 Maintenance & Repair 2,500.00 Total Other Charges 30,000.00 Total Judge/Executive 415,480.00 County Attorney 001-5005-101 Salaries-Elected Officials 46,650.00 001-5005-106 Salaries-Office Staff 91,775.00 Total Personnel Services 138,425.00 001-5005-315 Contracted Svs - Commonwealth Litigation Support 10,000.00 Total Contracted Services 10,000.00 Total County Attorney 148,425.00 County Clerk 001-5010-302 Advertising 3,500.00 001-5010-307 Auditing 17,500.00 001-5010-331 Lease Payments 36,500.00 001-5010-565 Printing, Stationary, Forms, Etc. 26,000.00 001-5010-585 Maintenance and Repairs 2,000.00 Total Other Charges 85,500.00 Total County Clerk 85,500.00 County Coroner 001-5020-101 Salaries-Elected Officials 38,100.00 001-5020-106 Salaries-Office Staff 65,950.00 Total Personnel Services 104,050.00 001-5020-308 Autopsies & Attendant Services 20,000.00 Total Contracted Services 20,000.00 Page 1 of 21 Approved (Ord. -

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

Poverty, Charity and the Papacy in The

TRICLINIUM PAUPERUM: POVERTY, CHARITY AND THE PAPACY IN THE TIME OF GREGORY THE GREAT AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTEENTH DAY OF MARCH, 2013 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ___________________________ Miles Doleac APPROVED: ________________________ Dennis P. Kehoe, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ F. Thomas Luongo, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ Thomas D. Frazel, Ph.D AN ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of Gregory I (r. 590-604 CE) in developing permanent ecclesiastical institutions under the authority of the Bishop of Rome to feed and serve the poor and the socio-political world in which he did so. Gregory’s work was part culmination of pre-existing practice, part innovation. I contend that Gregory transformed fading, ancient institutions and ideas—the Imperial annona, the monastic soup kitchen-hospice or xenodochium, Christianity’s “collection for the saints,” Christian caritas more generally and Greco-Roman euergetism—into something distinctly ecclesiastical, indeed “papal.” Although Gregory has long been closely associated with charity, few have attempted to unpack in any systematic way what Gregorian charity might have looked like in practical application and what impact it had on the Roman Church and the Roman people. I believe that we can see the contours of Gregory’s initiatives at work and, at least, the faint framework of an organized system of ecclesiastical charity that would emerge in clearer relief in the eighth and ninth centuries under Hadrian I (r. 772-795) and Leo III (r. -

"Years of Struggle": the Irish in the Village of Northfield, 1845-1900

SPRING 1987 VOL. 55 , NO. 2 History The GFROCE EDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Irish-born who moved into Northfield village arrived in impoverish ment, suffered recurrent prejudice, yet attracted other Irish to the area through kinship and community networks ... "Years of Struggle": The Irish in the Village of Northfield, 1845-1900* By GENE SESSIONS Most Irish immigrants to the United States in the nineteenth century settled in cities, and for that reason historians have focused on their experience in an urban-industrial setting. 1 Those who made their way to America's towns and villages have drawn less attention. A study of the settling-in process of nineteenth century Irish immigrants in the village of Northfield, Vermont, suggests their experience was similar, in im portant ways, to that of their urban counterparts. Yet the differences were significant, too, shaped not only by the particular characteristics of Northfield but also by adjustments within the Irish community itself. In the balance the Irish changed Northfield forever. The Irish who came into Vermont and Northfield in the nineteenth century were a fraction of the migration of nearly five million who left Ireland between 1845 and 1900. Most of those congregated in the cities along the eastern seaboard of the United States. Others headed inland by riverboats and rail lines to participate in settling the cities of the west. Those who traveled to Vermont were the first sizable group of non-English immigrants to enter the Green Mountain state. The period of their greatest influx was the late 1840s and 1850s, and they continued to arrive in declining numbers through the end of the century. -

Charlemagne's Heir

Charlemagne's Heir New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious (814-840) EDITED BY PETER' GOD MAN AND ROGER COLLINS CLARENDON PRESS . OXFORD 1990 5 Bonds of Power and Bonds of Association in the Court Circle of Louis the Pious STUART AIRLIE I TAKE my text from Thegan, from the well-known moment in his Life of Louis the Pious when the exasperated chorepiscopus of Trier rounds upon the wretched Ebbo, archbishop of Reims: 'The king made you free, not noble, since that would be impossible." I am not concerned with what Thegan's text tells us about concepts of nobility in the Carolingian world. That question has already been well handled by many other scholars, including JaneMartindale and Hans-Werner Goetz.! Rather, I intend to consider what Thegan's text, and others like it, can tell us about power in the reign of Louis the Pious. For while Ebbo remained, in Thegan's eyes, unable to transcend his origins, a fact that his treacherous behaviour clearly demonstrated, politically (and cultur- ally, one might add) Ebbo towered above his acid-tongued opponent. He was enabled to do this through his possession of the archbishopric of Reims and he had gained this through the largess of Louis the Pious. If neither Louis nor Charlemagne, who had freed Ebbo, could make him noble they could, thanks to the resources of patronage at their disposal, make him powerful, one of the potentes. It was this mis-use, as he saw it, of royal patronage that worried Thegan and it worried him because he thought that the rise of Ebbo was not a unique case. -

Prudentius of Troyes (D. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era

Prudentius of Troyes (d. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era by Jared G. Wielfaert A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Jared Wielfaert 2015 Prudentius of Troyes (d. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era Jared Gardner Wielfaert Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2015 ABSTRACT: This study concerns Prudentius, bishop of Troyes (861), a court scholar, historian, and pastor of the ninth century, whose extant corpus, though relatively extensive, remains unstudied. Born in Spain in the decades following the Frankish conquest of the Spanish march, Prudentius had been recruited to the Carolingian court under Louis the Pious, where he served as a palace chaplain for a twenty year period, before his eventual elevation to the see of Troyes in the 840s. With a career that moved from the frontier to the imperial court center, then back to the local world of the diocese and environment of cathedral libraries, sacred shrines, and local care of souls, the biography of Prudentius provides a frame for synthesis of several prevailing currents in the cultural history of the Carolingian era. His personal connections make him a rare link between the generation of the architects of the Carolingian reforms (Theodulf and Alcuin) and their students (Rabanus Maurus, Prudentius himself) and the great period of fruition of which the work of John Scottus Eriugena is the most widely recogized example. His involvement in the mid-century theological controversy over the doctrine of predestination illustrates the techniques and methods, as well as the concerns and preoccupations, of Carolingian era scholars engaged in the consolidation and interpretation of patristic opinion, particularly, that of Augustine. -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

M6-750/750S M6-760/760S M6-770/770S

M6-750/750S M6-760/760S M6-770/770S CHARACTERISTICS Microprocessor i486 DX2 @ 50 MHz M6-750 M6-750 S i486 DX2 @ 66 MHz M6-760 M6-760 S MOTHERBOARD INTEL DX4 @ 100 MHz M6-770 M6-770 S BA2080 Pre-production These are the processor’s internal clock boards only. rates. Clock M6-750 M6-750 S 25 MHz BA2123 Chip Set M6-760 M6-760 S 33 MHz Saturn step B 5 M6-770 M6-770 S 33 MHz BA2136 Chip Set Saturn step B with new Architecture ISA / PCI printed circuit. Memory RAM: minimum 8 MB, maximum 128 MB The motherboard has four sockets arranged BA2154 Chip Set in two separate banks capable of Saturn 2 accomodating the following SIMMs: BA2156 Chip Set EXM 28-004 No 1 1MB x 36 (4 MB) SIMM Saturn 2 with new EXM 28-008 No 1 2MB x 36 (8 MB) SIMM printed circuit. EXM 28-016 No 1 4MB x 36 (16 MB) SIMM o EXM 28-032 N 1 8MB x 36 (32 MB) SIMM BIOS - Two kits are always required. - The banks can host 8 MB, 16 MB, 32 MB The ROM BIOS is a or 64 MB. Mixed configurations can be Flash EPROM. The used. BIOS code is supplied - Different SIMMs cannot be used within on diskettes and must the same bank. be copied into the Flash EPROM. Memory access 70 ns Last level: Rel. 2.03 Cache - First level cache: 8 KB integrated in the processor - Secondary level cache: 128 KB or 256 KB capacity EXPANSION BUS Depending on the jumper settings, cache TIN BOX IN 2013 memory can work in either write back or IN 2022 write through mode. -

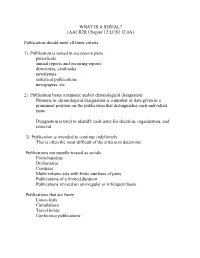

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors.