the Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currency Union Entries and Trade

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nitsch, Volker Working Paper Currency union entries and trade Diskussionsbeiträge, No. 2005/9 Provided in Cooperation with: Free University Berlin, School of Business & Economics Suggested Citation: Nitsch, Volker (2005) : Currency union entries and trade, Diskussionsbeiträge, No. 2005/9, ISBN 3938369086, Freie Universität Berlin, Fachbereich Wirtschaftswissenschaft, Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/28033 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Diskussionsbeiträge des Fachbereichs Wirtschaftswissenschaft der Freien Universität Berlin Nr. 2005/9 VOLKSWIRTSCHAFTLICHE REIHE Currency Union Entries and Trade Volker Nitsch ISBN 3-938369-08-6 May 6, 2005 Forthcoming: Jens Hölscher and Horst Tomann (eds.) Globalization of Capital Markets and Monetary Policy. -

Country, Capital, Currency

List of all Countries, Capitals & Currencies of the World Country Capital Currency Afghanistan Kabul Afghan afghani Albania Tirana Albanian lek Algeria Agiers Algerian dinar Andorra Andorra la Vella Euro Angola Luanda Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda St. John’s East Caribbean dollar Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine peso Armenia Yerevan Armenian dram Australia Canberra Australian dollar Austria Vienna Euro Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Nassau Bahamian dollar Bahrain Manama Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi taka Barbados Bridgetown Barbadian dollar Belarus Minsk Belarusian ruble Belgium Brussels Euro Belize Belmopan Belize dollar Benin Porto-Novo (official) West African CFA franc Bhutan Thimpu Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Sucre Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Gaborone Pula Brazil Brasília Brazilian real Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei dollar Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso Ouagadougou West African CFA franc Burundi Bujumbura Burundian franc Cambodia Phnom Penh Cambodian riel Cameroon Yaoundé Central African CFA franc Canada Ottawa Canadian dollar Cape Verde Praia Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Bangui Central African CFA franc Chad N’Djamena Central African CFA franc Chile Santiago Chilean peso China Beijing Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Bogotá Colombian peso Comoros Moroni Comorian franc Costa Rica San José Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Yamoussoukro (official),Abidjan West African CFA franc (seat of government) Croatia -

The Euro and the CFA Franc: Evidence of Sectoral Trade Effects

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Martínez-Zarzoso, Inmaculada Working Paper The Euro and the CFA Franc: Evidence of sectoral trade effects cege Discussion Papers, No. 311 Provided in Cooperation with: Georg August University of Göttingen, cege - Center for European, Governance and Economic Development Research Suggested Citation: Martínez-Zarzoso, Inmaculada (2017) : The Euro and the CFA Franc: Evidence of sectoral trade effects, cege Discussion Papers, No. 311, University of Göttingen, Center for European, Governance and Economic Development Research (cege), Göttingen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/157628 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Farewell to the CFA Franc: Macron and Ouattara End a Colonial Relic - WSJ

12/31/2019 Farewell to the CFA Franc: Macron and Ouattara End a Colonial Relic - WSJ COOKIE NOTICE We use cookies for analytics, advertising and to improve our site. You agree to our use of cookies by closing this message box or continuing to use our site. To ind out more, including how to change your settings, see our Cookie Policy This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/farewell-to-the-cfa-franc-macron-and-ouattara-end-a-colonial-relic-11577751037 OPINION | COMMENTARY Farewell to the CFA Franc: Macron and Ouattara End a Colonial Relic The eco, West Africa’s new money, would be sounder if accompanied by a currency board. By Steve H. Hanke Dec. 30, 2019 710 pm ET French President Emmanuel Macron and Ivoirian President Alassane Ouattara in Bouake, Ivory Coast, Dec. 22. PHOTO: LUDOVIC MARINAGENCE FRANCEPRESSEGETTY IMAGES French President Emmanuel Macron and Alassane Ouattara, president of the Ivory Coast, have delivered the coup de grâce to a colonial relic: the CFA franc. Created in 1945, the CFA franc is the only colonial currency arrangement still in existence. Fourteen African countries constitute the CFA franc zone. These countries in West and Central Africa are split into two separate economic and monetary unions in which the CFA franc is the coin of the realm. But the two presidents announced Dec. 21 that when the new year is rung in, the currency will disappear in the eight countries of the West African zone—home to 130 million people—and be replaced by a new one, the eco. -

Average Exchange Rates: March 2009 – September 2009 and Inflation Rates of Gef Donors

GEF/R.5/Inf.27 February 12, 2010 Sixth Meeting for the Fifth Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund May 12, 2010 Paris, France AVERAGE EXCHANGE RATES: MARCH 2009 – SEPTEMBER 2009 AND INFLATION RATES OF GEF DONORS (PREPARED BY THE WORLD BANK AS TRUSTEE) AVERAGE EXCHANGE RATES: MARCH 2009 – SEPTEMBER 2009 AND INFLATION RATES OF GEF DONORS 1. This note provides (i) the final reference exchange rates for the GEF-5 Replenishment, (ii) the Inflation Rates of GEF Donors during 2006-2008, and (iii) a comparison of the GEF-5 reference exchange rates with those of the GEF-4. 2. At the first GEF-5 replenishment meeting, the Contributing Participants agreed that the seven-month period from March 1, 2009 to September 30, 2009 would be the reference time period to be used for translating the GEF-5 donor contributions between SDR values and national currency values. 3. Contributing Participants also agreed that, consistent with practice in previous replenishments, donor countries experiencing annual average inflation rates of over 10 percent during the preceding three-year period would denominate their GEF-5 contributions in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). At the second meeting for the GEF-5 replenishment the Trustee provided Contributing Participants with average inflation rates for the 2006-2008 period.1 4. Annex 1 presents the final GEF-5 reference exchange rates to be used to translate the SDR contributions into commitment currencies. 5. Annex 2 presents the inflation rates table presented in June 2009 updated to reflect the addition of Côte d’Ivoire who attended the June 2009 GEF-5 replenishment meeting as a Contributing Participant and Russian Federation who announced their plans to contribute to the GEF-5 during the November 2009 GEF-5 replenishment meeting. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

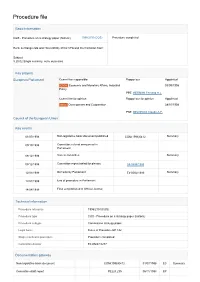

Procedure File

Procedure file Basic information COS - Procedure on a strategy paper (historic) 1998/2151(COS) Procedure completed Euro: exchange rate and convertibility of the CFA and the Comorian franc Subject 5.20.02 Single currency, euro, euro area Key players European Parliament Committee responsible Rapporteur Appointed ECON Economic and Monetary Affairs, Industrial 03/09/1998 Policy PPE HERMAN Fernand H.J. Committee for opinion Rapporteur for opinion Appointed DEVE Development and Cooperation 28/10/1998 PSE DELCROIX Claude A.F. Council of the European Union Key events 01/07/1998 Non-legislative basic document published COM(1998)0412 Summary 09/10/1998 Committee referral announced in Parliament 08/12/1998 Vote in committee Summary 08/12/1998 Committee report tabled for plenary A4-0484/1998 12/01/1999 Decision by Parliament T4-0002/1999 Summary 12/01/1999 End of procedure in Parliament 14/04/1999 Final act published in Official Journal Technical information Procedure reference 1998/2151(COS) Procedure type COS - Procedure on a strategy paper (historic) Procedure subtype Commission strategy paper Legal basis Rules of Procedure EP 142 Stage reached in procedure Procedure completed Committee dossier ECON/4/10277 Documentation gateway Non-legislative basic document COM(1998)0412 01/07/1998 EC Summary Committee draft report PE228.235 06/11/1998 EP Committee opinion DEVE PE228.201/DEF 02/12/1998 EP Committee report tabled for plenary, single A4-0484/1998 08/12/1998 EP reading OJ C 104 14.04.1999, p. 0004 Text adopted by Parliament, single reading T4-0002/1999 12/01/1999 EP Summary OJ C 104 14.04.1999, p. -

Legal and Institutional Framework for Monetary Integration in West Africa

Legal and Institutional Framework for Monetary Integration in West Africa Kenneth O.D. Okwor ABSTRACT The literature on monetary integration in West Africa focuses, almost exclusively, on the economic and political preconditions for, and consequences of, such integration. Very little attention has been paid to the legal and institutional framework that make such monetary arrangements possible. This paper fills that gap and concludes that the current framework is inefficient and will impede the instatement of the Eco as a single currency for a West African currency union. This conclusion is predicated on evidence generated from a punctilious review and comparative analysis of the applicable treaties, protocols, agreements, decisions, laws and internal policies comprising the current legal and institutional framework for monetary integration in West Africa. In particular, this paper finds that the current framework: (i) is inefficient and costly on account of the multiplicity of laws and institutions, and the horizontal and vertical duplication of institutions and functions; (ii) is unenforceable, in the sense that it lacks direct effect and/or applicability within ECOWAS member states; (iii) makes the currency union’s institutions susceptible to capture; (iv) relies on ‘dependent’ national central banks, and a weak and inefficient mechanism for multilateral surveillance; (v) provides an ineffective agency of restraint on fiscal indiscipline; and (vi) does very little in addressing the moral hazard and incentive problems that are inherent in the creation of a currency union. Legal and Institutional Framework for Monetary Integration in West Africa 1. Introduction This research aims to appraise critically the legal and institutional framework for monetary integration in West Africa. -

Eff Welcomes the 8 West African Countries That Have Broken Away from French Colonial Era Currency

EFF WELCOMES THE 8 WEST AFRICAN COUNTRIES THAT HAVE BROKEN AWAY FROM FRENCH COLONIAL ERA CURRENCY Sunday, 22 December 2019 The EFF welcomes the collective decision taken by former French colonies of West Africa to break away from the CFA franc, a French backed regional currency that dates back to the colonial era. This is a significant move, long overdue, that asserts total financial decolonisation and dependence on the imperialist state of France. The West African CFA franc currency was used by Benin, Burkina Faso, the Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. It limited the monetary sovereignty of these countries. Essentially, France guaranteed the value of the CFA franc and in return, the West African countries were required to keep 50% of their foreign exchange reserves with the French treasury. Due to the fact that the exchange rate between the CFA franc and euro is fixed, the central banks of the two CFA franc zones need to follow the monetary policies of the European Central Bank. In essence, the European Central Bank sets interest rates for countries that use the CFA franc. This decision must therefore be welcome to afford the West African region monetary sovereignty and trade advantage. Above all, we welcome the decision to replace the CFA franc with the ECO; a Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) currency which is planned for implementation in 2020. P1 The EFF calls for the former French territories of the Central African countries that still use the CFA franc and keep 50% of their foreign reserves in the French Central Bank to also follow in the example set by West Africa. -

All Countries and Their Currency Names List

List of all Countries and Currencies of the World in 2020 Country Currency Afghanistan Afghan afghani Albania Albanian lek Algeria Algerian dinar Andorra Euro Angola Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar Argentina Argentine peso Armenia Armenian dram Australia Australian dollar Austria Euro Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Bahamian dollar Bahrain Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka Barbados Barbadian dollar Belarus Belarusian ruble Belgium Euro Belize Belize dollar Benin West African CFA franc Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Pula Brazil Brazilian real Brunei Brunei dollar Bulgaria Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso West African CFA franc Burundi Burundian franc Cambodia Cambodian riel Cameroon Central African CFA franc Canada Canadian dollar Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Central African CFA franc Chad Central African CFA franc Chile Chilean peso China Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Colombian peso Comoros Comorian franc Costa Rica Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) West African CFA franc Croatia Croatian kuna Cuba Cuban peso Cyprus Euro Czechia Czech koruna Democratic Republic of the Congo Congolese franc Denmark Danish krone Djibouti Djiboutian franc Dominica East Caribbean dollar Dominican Republic Dominican peso Ecuador United States dollar Egypt Egyptian pound El Salvador United States dollar Equatorial Guinea Central African CFA franc Eritrea Eritrean nakfa Estonia Euro Ethiopia Ethiopian -

20 000,00 $ Can Sample Table of the Maximum Contribution In

SAMPLE TABLE OF THE MAXIMUM CONTRIBUTION IN LOCAL CURRENCY Date: July 8, 2016 20 000,00 $ CAN COUNTRY CURRENCY CAN$1 = AMOUNT IN LOCAL CURRENCY South Africa ZAR - South African Rand 11,8511 237 022 ZAR Bangladesh BDT - Bangladeshi Taka 61,1799 1 223 598 BDT Benin XOF - West African CFA Franc 452,5570 9 051 140 XOF Bolivia BOB - Bolivian Boliviano 5,3629 107 257 BOB Brazil BRL - Brazilian Real 2,6810 53 620 BRL Burkina Faso XOF - West African CFA Franc 452,5570 9 051 140 XOF Burundi BIF - Burundian Franc 1 291,2600 25 825 200 BIF Cameroon XAF - Central African CFA Franc 452,5570 9 051 140 XAF Chile CLP - Chilean Peso 529,3806 10 587 612 CLP Colombia COP - Columbian Peso 2 314,8148 46 296 296 COP Ivory Coast XOF - West African CFA Franc 452,5570 9 051 140 XOF Cuba CUC - Cuban Convertible Peso 0,7789 15 577 CUC El Salvador SVC - Salvadoran Colon 0,7668 15 336 USD Ecuador USD - United States Dollar 0,7668 15 336 USD United States USD - United States Dollar 0,7668 15 336 USD Europe EUR - Euro 0,6873 13 746 EUR Ghana GHS - Ghanaian Cedi 3,0093 60 186 GHS Guatemala GTQ - Guatemalan Quetzal 6,0024 120 048 GTQ Guinea GNF - Guinean Franc 5 726,8900 114 537 800 GNF Haiti HTG - Haitian Gourde 48,7618 975 236 HTG Honduras HNL - Honduran Lempira 17,4216 348 432 HNL India INR - Indian Rupee 51,7063 1 034 126 INR Indonesia IDR - Indonesian Rupiah 10 204,0816 204 081 632 IDR Kenya KES - Kenyan Shilling 78,8467 1 576 934 KES Lesotho LSL - Lesotho Loti 11,8168 236 336 LSL Madagascar MGA - Malagasy Ariary 2 539,0700 50 781 400 MGA Malawi MWK - Malawian Kwacha