12.2% 125,000 140M Top 1% 154 5,000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strada Romantica Sinio Di Langhe E Roero

Vezza d'Alba Magliano Alfieri Neive Treiso Per info e prenotazioni Trezzo Terre Alte Tinella Escursioni guidate Tel 333 466 33 88 www.terrealte.cn.it Benevello Strada Romantica Sinio di Langhe e Roero www.stradaromantica.it Murazzano Cissone Mombarcaro Camerana Settembre Ottobre 2011 2011 Domenica 4: Treiso Domenica 2: Castino Le rocche dei sette fratelli L’anello della Lodola Ritrovo: ore 10, Treiso (Municipio). Quota: 7 € Ritrovo: ore 10, Castino (Piazza del Mercato). Quota: 7 €. In collaborazione con Comune di Alba e Parco Culturale Piemonte Paesaggio Umano Passeggiata di circa 10 km tra i vigneti di nebbiolo e moscato, molto interessante dal punto di vista paesaggistico e geologico per le Escursione ad anello di circa 10 km sulla collina di Castino, nei luoghi spettacolari rocche che caratterizzano questa collina: si percorrono i descritti ne "Il partigiano Johnny". Percorso di grande interesse letterario e luoghi presenti nelle opere di Fenoglio. paesaggistico. Al termine proiezione di immagini sulla Resistenza. Domenica 11: Torre Bormida - Cravanzana Domenica 9: Alba L’anello della nocciola Sulle tracce di Fulvia Ritrovo: ore 10, Torre Bormida (piscina comunale). Quota: 7 €. Ritrovo: ore 10, Alba (Piazza Duomo). Quota: 7 €. In collaborazione con Comune di Alba e Parco Culturale Piemonte Paesaggio Umano Trekking naturalistico di circa 12 km, senza difficoltà tecniche: sentieri e stradine tra boschi e noccioleti ci faranno scoprire "sul campo" uno Trekking letterario di circa 12 km sui sentieri e le stradine lungo dei prodotti più tipici di questo territorio. A Cravanzana sosta per una la cresta di Altavilla e la valle di San Rocco Seno D’Elvio, dove degustazione di nocciole e di dolci artigianali. -

Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian Border

Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian border 97 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian border 98 Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian border A variation of the GTL hillcrest route, this brief section takes you down the hillside to the outer edge of the region, where the hills continue out into the region of Liguria. DISTANCE/PROFILE ELEVATION GAIN DIFFICULTY START FINISH 5 km 695 m 425 m OC Itinerary profle 695 m 455 m 425 m 0 Km 3,8 Km 5 Km Gottasecca Valle Ligurian border GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian border 99 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Variant Gottasecca – Ligurian border 102 Gottasecca is the last of the hillcrest villages and awaits you out where the hill descends towards the ample valley of Contrada di Camerana and then Saliceto, the farthest corner of the Piedmont region. Gottasecca owes its fame to two local celebrities. The frst was the historical fgure of Amedeo Ravina, an Italian poet and true patriot in Italy’s unifcation movement, something of a Sándor Petőf for the Piedmont region. He spent 27 years in exile and was involved in every revolutionary action between 1821 and 1848 in the Piedmont region, in Spain, in France and then back in Italy. He came back to Italy in 1848 during the time of King Charles Albert and the Albertine Statute and became a deputy of the Subalpine Parliament nearly until his death, just a few years prior to the unifcation of Italy. The second is a local sports celebrity, Felice Bertola, one of the great champions of balon (or pallapugno), the popular local sport here in the Langhe. -

Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio

Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio 197 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio 198 Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio A brief, uphill section from the hazelnut groves to the realm of mushrooms and trufes, immersed in the history of these villages and the authenticity of nature. DISTANCE/PROFILE ELEVATION GAIN DIFFICULTY START FINISH 5,5 km 570 m 695 m BC Itinerary profle 695 m 570 m 0 Km 5,5 Km Cravanzana Feisoglio GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio 199 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 15 Cravanzana – Feisoglio 202 Although the village’s coat of arms bears the image of a goat, Cravanzana Cerretto. This long strip of village runs parallel to the massive Church of is the realm of the hazelnut. Cravanzana has the most beautifully preserved San Lorenzo, which looms over the village in the same way the castle castle of the entire Belbo Valley, partly because so many others have surely once did just to the south, although now only a few stones of the been destroyed, but also because this one is truly monumental. Now foundation remain, the castle having been destroyed during the wars of privately owned, it may be visited on special occasions, such as within the 17th century. the scope of the “Castelli Aperti” (Open Castles) initiative. Its current Outside the town, trees rule the land, both in the untamed woods of form is partly due to restructuring work done in the 17th century, which mushrooms, trufes, wild bore and deer and in the hazelnut groves, transformed the castle into a more comfortable residence with a garden which are as popular here as the vineyards of Nebbiolo grapes in the for the Fontana Family, members of the new aristocracy under the House Bassa Langa. -

Case Study Italy

TOWN Small and medium sized towns in their functional territorial context Applied Research 2013/1/23 Case Study Report | Italy Version 15/February/2014 ESPON 2013 1 This report presents the interim results of an Applied Research Project conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2013 Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The partnership behind the ESPON Programme consists of the EU Commission and the Member States of the EU27, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Each partner is represented in the ESPON Monitoring Committee. This report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the Monitoring Committee. Information on the ESPON Programme and projects can be found on www.espon.eu The web site provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This basic report exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON & University of Leuven, 2013. Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON Coordination Unit in Luxembourg. ESPON 2013 2 List of authors Cristiana Cabodi (Officina Territorio) Alberta de Luca (Officina Territorio) Alberto Di Gioia (Politecnico di Torino) Alessia Toldo (Officina Territorio) ESPON 2013 3 Table of contents 1. National context (p. 9) 1.1 Semantic point of view (p. 9) 1.2 Institutional and administrative point of view (p. 9) 1.3 statistical point of view (p. 9) 1.4 Small and Medium Sized Towns (SMSTs) in National/Regional settlement system: literary overview (p 12.) 1.4.1 The Italian urban system from the 1960s to the 1970s: the polarized structure (p. -

Localita' Cap Provincia Abetone Cutigliano 51024 Pt

Elenco CAP/Località Periferiche aggiornato al 14 gennaio 2019 L'elenco che segue può subire variazioni. Si consiglia di scaricarlo una volta al mese. LOCALITA' CAP PROVINCIA ABETONE CUTIGLIANO 51024 PT ABRIOLA 85010 PZ ACCEGLIO 12021 CN ACCUMOLI 02011 RI ACERNO 84042 SA ACQUARIA 41025 MO AGAGGIO INFERIORE 18010 IM AGRA 21010 VA AIRETTA 28827 VB AIROLE 18030 IM AISONE 12010 CN ALA DI STURA 10070 TO ALAGNA VALSESIA 13021 VC ALBANETO 02016 RI ALBARETO 43051 PR ALBARETTO DELLA TORRE 12050 CN ALBERA LIGURE 15060 AL ALBERONA 71031 FG ALBOGASIO 22010 CO ALBUGNANO 14022 AT ALFERO 47028 FC ALGUA 24010 BG ALICE SUPERIORE 10010 TO ALLEGREZZE 16049 GE ALPEPIANA 16048 GE ALPICELLA 17019 SV ALTAGNANA 54100 MS ALTARE 17041 SV ALTIPIANI DI ARCINAZZO 00020 RM ALTO 12070 CN ALTO RENO TERME 40046 BO ALTO SERMENZA 13029 VC AMBORZASCO 16049 GE ANDONNO 12010 CN ANDRATE 10010 TO ANGROGNA 10060 TO APRICALE 18035 IM AQUILA DI ARROSCIA 18020 IM ARAMENGO 14020 AT ARCINAZZO ROMANO 00020 RM AREMOGNA 67037 AQ ARGENTERA 12010 CN ARGUELLO 12050 CN ARINA 32033 BL ARMO 18026 IM ARNASCO 17032 SV ARSIERO 36011 VI ARZENO D'ONEGLIA 18022 IM ASIAGO 36012 VI ASTA NELL'EMILIA 42030 RE ATELETA 67030 AQ AURIGO 18020 IM AVAGLIO 51010 PT AVENALE 62011 MC AVERARA 24010 BG AZZANO 55047 LU BACENO 28861 VB BADALUCCO 18010 IM BADIA PRATAGLIA 52014 AR BADIA TEDALDA 52032 AR BAGNARIA 27050 PV BAGNASCO 12071 CN BAGNI DI LUCCA 55022 LU BAGNI DI LUCCA VILLA 55022 LU BAGNI DI VINADIO 12010 CN BAGNO DI ROMAGNA 47021 FC BAISO 42031 RE BAJARDO 18031 IM BALESTRINO 17020 SV BALME 10070 TO BALMUCCIA -

Zone Del Sistema Confartigianato Cuneo -> Comuni

“Allegato B” UFFICI DI ZONA DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE CONFARTIGIANATO IMPRESE CUNEO Zone e loro limitazione territoriale. Elenco Comuni. Zona di ALBA Alba Albaretto della Torre Arguello Baldissero d’Alba Barbaresco Barolo Benevello Bergolo Borgomale Bosia Camo Canale Castagnito Castelletto Uzzone Castellinaldo Castiglione Falletto Castiglione Tinella Castino Cerretto Langhe Corneliano d’Alba Cortemilia Cossano Belbo Cravanzana Diano d’Alba Feisoglio Gorzegno Govone Grinzane Cavour Guarene Lequio Berria Levice Magliano Alfieri Mango Montà Montaldo Roero Montelupo Albese Monteu Roero Monticello d’Alba Neive Neviglie Perletto Pezzolo Valle Uzzone Piobesi d’Alba Priocca Rocchetta Belbo Roddi Rodello Santo Stefano Belbo Santo Stefano Roero Serralunga d’Alba Sinio Tone Bormida Treiso Trezzo Tinella Vezza d’Alba Zona di BORGO SAN DALMAZZO Aisone Argentera Borgo San Dalmazzo Demonte Entracque Gaiola Limone Piemonte Moiola Pietraporzio Rittana Roaschia Robilante Roccasparvera Roccavione Sambuco Valdieri Valloriate Vernante Vinadio Zona di BRA Bra Ceresole d’Alba Cervere Cherasco La Morra Narzole Pocapaglia Sanfrè Santa Vittoria d’Alba Sommariva del Bosco Sommariva Perno Verduno Zona di CARRÙ Carrù Cigliè Clavesana Magliano Alpi Piozzo Rocca Cigliè Zona di CEVA Alto Bagnasco Battifollo Briga Alta Camerana Caprauna Castellino Tanaro Castelnuovo di Ceva Ceva Garessio Gottasecca Igliano Lesegno Lisio Marsaglia Mombarcaro Mombasiglio Monesiglio Montezemolo Nucetto Ormea Paroldo Perlo Priero Priola Prunetto Roascio Sale delle Langhe Sale San Giovanni Saliceto -

Legenda T Braglia Lesegno T .! Torelli O Casc

1:70.000 Ü Presidio del Territorio PIANO FAUNISTICO VENATORIO PROVINCIALE 2003-2008 Legge 11 febbraio 1992, n. 157 articolo 10 Legge regionale 4 settembre 1996, n. 70 articolo 6 Deliberazione del Consiglio Provinciale n. 10-32 del 30 giugno 2003 Deliberazione della Giunta Regionale n. 102-10160 del 28 luglio 2003 Deliberazione della Giunta Provinciale n. 105 del 24.03.2009 e n. 47 del 30.04.2012 Deliberazione della Giunta Provinciale n. 20 del 04/05/2018 Starderi Base cartografica: CTR numerica 1/10.000 - Regione Piemonte - Settore Cartografico (autorizzazione n. 6/2002). Manzotti Cartografia ed elaborazioni GIS:Provincia di Cuneo - Settore Presidio del Territorio Pelizzeri ([email protected]) Balluri ZRC - Castiglione - Ettari 163,582011 Corso Nizza 21 – 12100 CUNEO http://www.provincia.cuneo.it/tutela_fauna/index.jsp Serra Grilli Coazzolo Neive .! Castiglione Tinella Rivetti .! Borgonuovo Serra Boella San Carlo Stazione Bric San Cristoforo Cotta Moniprandi ZRC - Valdivilla - Ettari 140,719273 Moretta Casasse Valdivilla ATC CN3 Bricco di Neive Santo Stefano Belbo ROERO .! Robini Ferrere San Maurizio ZRC - Santo Stefano - Ettari 157,953696 a CA CN1 l ATC CN2 Macarini l VALLE PO SALUZZO - SAVIGLIANO e n i T Riforno Domere ATC CN4 Giacosa S. Libera e CA CN2 ALBA - DOGLIANI t n Camo VALLE VARAITA ! e . r r Neviglie Macchia ATC CN5 o .! San Adriano Casc. Monsignore Treiso T ATC CN1 CORTEMILIA .! CA CN3 CUNEO - FOSSANO Mango VALLI MAIRA E GRANA .! Mad. della Rovere CA CN4 Trezzo Tinella .! Pianella VALLE STURA CA CN6 Leomonte VALLI MONREGALESI Meruzzano CA CN5 Naranzana VALLI GESSO, VERMENAGNA E PESIO ZRC - Cossano - Ettari 217,055045 CA CN7 .! ALTA VALLE TANARO La Cappelleta Casc. -

Mortalità Per TUMORI MALIGNI DELLE CAVITA' NASALI, DELL'orecchio MEDIO E DEI SENI ACCESSORI 1 Uomini, Tutte Le Età

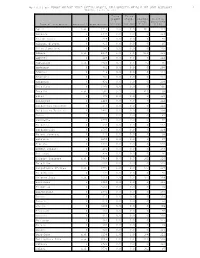

Mortalità per TUMORI MALIGNI DELLE CAVITA' NASALI, DELL'ORECCHIO MEDIO E DEI SENI ACCESSORI 1 Uomini, tutte le età Tasso Tasso grezzo stand. Rischio Rischio X X stand. bayesiano Area di residenza osservati popolazione 100.000 100.000 X 100 X 100 Agliè n.d. 1216 2.6 2.3 381 111 Airasca 0 1698 0.0 0.0 0 114 Ala di Stura 0 229 0.0 0.0 0 94 Albiano d'Ivrea 0 816 0.0 0.0 0 95 Alice Superiore 0 280 0.0 0.0 0 115 Almese n.d. 2617 1.2 1.4 210 110 Alpette 0 127 0.0 0.0 0 112 Alpignano n.d. 7920 0.4 0.4 91 95 Andezeno 0 841 0.0 0.0 0 108 Andrate 0 219 0.0 0.0 0 111 Angrogna 0 405 0.0 0.0 0 154 Arignano 0 431 0.0 0.0 0 109 Avigliana 0 5196 0.0 0.0 0 105 Azeglio n.d. 587 5.3 5.5 823 99 Bairo 0 370 0.0 0.0 0 112 Balangero 0 1429 0.0 0.0 0 112 Baldissero Canavese 0 244 0.0 0.0 0 112 Baldissero Torinese 0 1490 0.0 0.0 0 108 Balme 0 47 0.0 0.0 0 81 Banchette 0 1774 0.0 0.0 0 85 Barbania 0 693 0.0 0.0 0 112 Bardonecchia 0 1585 0.0 0.0 0 114 Barone Canavese 0 273 0.0 0.0 0 98 Beinasco 0 9152 0.0 0.0 0 67 Bibiana 0 1392 0.0 0.0 0 133 Bobbio Pellice 0 291 0.0 0.0 0 158 Bollengo 0 978 0.0 0.0 0 96 Borgaro Torinese n.d. -

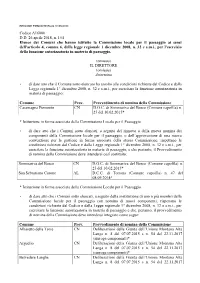

Codice A16000 D.D. 26 Aprile 2018, N. 154 Elenco Dei Comuni Che Hanno

REGIONE PIEMONTE BU22 31/05/2018 Codice A16000 D.D. 26 aprile 2018, n. 154 Elenco dei Comuni che hanno istituito la Commissione locale per il paesaggio ai sensi dell'articolo 4, comma 6, della legge regionale 1 dicembre 2008, n. 32 e s.m.i., per l'esercizio della funzione autorizzatoria in materia di paesaggio. (omissis) IL DIRETTORE (omissis) determina • di dare atto che il Comune sotto elencato ha assolto alle condizioni richieste dal Codice e dalla Legge regionale 1° dicembre 2008, n. 32 e s.m.i., per esercitare la funzione autorizzatoria in materia di paesaggio: Comune Prov. Provvedimento di nomina della Commissione Caramagna Piemonte CN D.G.C. di Sommariva del Bosco (Comune capofila) n. 25 del 10.02.2015* * Istituzione in forma associata della Commissione Locale per il Paesaggio • di dare atto che i Comuni sotto elencati, a seguito del rinnovo o della nuova nomina dei componenti della Commissione locale per il paesaggio, o dell’approvazione di una nuova convenzione per la gestione in forma associata della stessa Commissione, rispettano le condizioni richieste dal Codice e dalla Legge regionale 1° dicembre 2008, n. 32 e s.m.i., per esercitare la funzione autorizzatoria in materia di paesaggio, e che pertanto, il Provvedimento di nomina della Commissione deve intendersi così sostituito: Sommariva del Bosco CN D.G.C. di Sommariva del Bosco (Comune capofila) n. 25 del 10.02.2015* San Sebastiano Curone AL D.C.C. di Tortona (Comune capofila) n. 47 del 08.09.2014* * Istituzione in forma associata della Commissione Locale per il Paesaggio • di dare atto che i Comuni sotto elencati, a seguito della sostituzione di uno o più membri della Commissione locale per il paesaggio con nomina di nuovi componenti, rispettano le condizioni richieste dal Codice e dalla Legge regionale 1° dicembre 2008, n. -

Leg 11 Albaretto Della Torre - Benevello

Leg 11 Albaretto della Torre - Benevello 165 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 11 Albaretto della Torre - Benevello 166 Leg 11 Albaretto della Torre - Benevello A hillcrest section that takes you to Pavaglione. This section features some stunning views and from Albaretto you can also head down in the opposite direction in a wide circle to switch valleys and reach the other crest of the GTL. DISTANCE/PROFILE ELEVATION GAIN DIFFICULTY START FINISH 10 km 670 m 640 m BC Itinerary profle 670 m 640 m 0 Km 10 Km Albaretto della Torre Benevello GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 11 Albaretto della Torre - Benevello 167 GTL - Grande Traversata delle Langhe • Leg 11 Albaretto della Torre - Benevello 170 As you leave Albaretto della Torre in the direction of Tre Cunei, this route the farmhouse Pian dei Gatti. passes right in front of “Botega ‘d Cesare”, right across from the church Continue to the left and follow along the main highway for about 600 metres of San Bernardo, before you climb up to the left to Strada Fontanassino. (less than half a mile) to an intersection in the fat. From here, turn right and This narrow street, which is closed to trafc and adorned with the Stages head back up a somewhat faint dirt road along the crest of the hill. The of the Cross, winds past the fountain, for which it is named, to the hillcrest road will become more evident and continue along or near the crest. This highway. Watch for cars and follow the highway to the left. -

Medie Radon Provincia Cuneo 2017

Provincia Comune media radon al piano terra (Bq/m 3) Cuneo Acceglio 133 Cuneo Aisone 149 Cuneo Alba 99 Cuneo Albaretto della torre 79 Cuneo Alto 498 Cuneo Argentera 216 Cuneo Arguello 79 Cuneo Bagnasco 112 Cuneo Bagnolo Piemonte 135 Cuneo Baldissero d'Alba 105 Cuneo Barbaresco 89 Cuneo Barge 145 Cuneo Barolo 85 Cuneo Bastia mondovi' 108 Cuneo Battifollo 96 Cuneo Beinette 160 Cuneo Bellino 80 Cuneo Belvedere Langhe 79 Cuneo Bene Vagienna 148 Cuneo Benevello 79 Cuneo Bergolo 81 Cuneo Bernezzo 102 Cuneo Bonvicino 79 Cuneo Borgo San Dalmazzo 133 Cuneo Borgomale 79 Cuneo Bosia 87 Cuneo Bossolasco 79 Cuneo Boves 140 Cuneo Bra 146 Cuneo Briaglia 82 Cuneo Briga Alta 125 Cuneo Brondello 120 Cuneo Brossasco 118 Cuneo Busca 148 Cuneo Camerana 83 Cuneo Camo 80 Cuneo Canale 107 Cuneo Canosio 130 Cuneo Caprauna 602 Cuneo Caraglio 63 Cuneo Caramagna Piemonte 157 Cuneo Carde' 155 Cuneo Carru' 147 Cuneo Cartignano 116 Cuneo Casalgrasso 154 Cuneo Castagnito 92 Cuneo Casteldelfino 90 Cuneo Castellar 143 Cuneo Castelletto Stura 154 Cuneo Castelletto Uzzone 81 Cuneo Castellinaldo 98 Cuneo Castellino Tanaro 85 Cuneo Castelmagno 96 Cuneo Castelnuovo di Ceva 99 Cuneo Castiglione Falletto 94 Cuneo Castiglione Tinella 81 Cuneo Castino 81 Cuneo Cavallerleone 161 Cuneo Cavallermaggiore 160 Cuneo Celle di Macra 73 Cuneo Centallo 159 Cuneo Ceresole d'Alba 151 Cuneo Cerretto Langhe 79 Cuneo Cervasca 142 Cuneo Cervere 151 Cuneo Ceva 105 Cuneo Cherasco 140 Cuneo Chiusa di Pesio 147 Cuneo Ciglie' 98 Cuneo Cissone 79 Cuneo Clavesana 94 Cuneo Corneliano d'Alba 104 Cuneo -

Comuni Distretti Sanitari Fascia Rischio 1 Comuni Distretti Sanitari Fascia Rischio 1

COMUNI DISTRETTI SANITARI_FASCIA RISCHIO_1 COMUNI DISTRETTI SANITARI_FASCIA RISCHIO_1 DISTRETTO COMUNE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) AGLIANO TERME AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) BELVEGLIO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) BRUNO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) BUBBIO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CALAMANDRANA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CALOSSO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CANELLI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASSINASCO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTAGNOLE DELLE LANZE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTEL BOGLIONE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTEL ROCCHERO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTELLETTO MOLINA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTELNUOVO BELBO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CASTELNUOVO CALCEA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CESSOLE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) COAZZOLO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) CORTIGLIONE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) COSTIGLIOLE D'ASTI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) FONTANILE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) INCISA SCAPACCINO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) LOAZZOLO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MOASCA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MOMBARUZZO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MOMBERCELLI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MONASTERO BORMIDA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MONTABONE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MONTALDO SCARAMPI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) MONTEGROSSO D'ASTI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) NIZZA MONFERRATO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) OLMO GENTILE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) QUARANTI AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) ROCCAVERANO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) ROCCHETTA PALAFEA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) SAN MARZANO OLIVETO AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) SEROLE AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) SESSAME AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) VAGLIO SERRA AT - As sud (Nizza M.to) VESIME AT - As sud (Nizza