Interactions Affecting Farmland Birds Around Forest Plantations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oriole Birding Tour Report

ORIOLE BIRDING TOUR REPORT PYRENEES & STEPPES 28TH FEBRUARY – 4TH MARCH 2016 www.oriolebirding.com [email protected] SUNDAY 28TH FEBRUARY – Sunny spells and 11C in Barcelona, -2.5C in mountains Our long first day started at 0530 in Gatwick Airport North Terminal for the 0730 flight to Barcelona which departed bang on time, arriving just over 90 minutes later to sunshine and pleasant temperatures. We met with our local guide Carles and quickly collected our minibus, before proceeding straight to the Llobregat Delta on the outskirts of the airport where it is possible to kick start the trip list with a good variety of wetland species. The most noteworthy sighting as we made our way along the main canal towards the reserve entrance, were the large numbers of Crag Martins feeding over the water and adjacent reeds – there were probably hundreds on the area, mixed with a few Barn Swallows, Sand Martins and House Martins, and we enjoyed some superb views. Common Chiffchaff, Blackcap, Common Stonechat and European Serin were seen along the 1km walk towards the hides, and a drake Red Crested Pochard was roosting at the reed edge with Northern Shovelers. At the main hide, a spread of ducks included many Common Teal and Common Pochard, Gadwall and a couple of waders – Common Snipe and a Little-ringed Plover. Carles spotted a Little Bittern, the first of the spring, skulking at the reed edge and another or the same flew low past the hide. Our main target was Moustached Warbler, and we spent some time checking a favoured spot, but we didn’t even hear one – time was not really on our side and we reluctantly had to move on. -

Effectiveness of SRDP in Corn Bunting Conservation: Assessing the Impact of Six Years of Targeted Agri-Environment Schemes

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 941 Effectiveness of SRDP in corn bunting conservation: assessing the impact of six years of targeted agri-environment schemes COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 941 Effectiveness of SRDP in corn bunting conservation: assessing the impact of six years of targeted agri-environment schemes For further information on this report please contact: Dr Jessica Shaw Scottish Natural Heritage Battleby Redgorton PERTH PH1 3EW Telephone: 01738 458675 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Perkins, A.J., Maggs, H., Stephan, Y., Corrigan, A. & Wilson, J.D. 2017. Effectiveness of SRDP in corn bunting conservation: assessing the impact of six years of targeted agri- environment schemes. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 941. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2017. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Effectiveness of SRDP in corn bunting conservation: assessing the impact of six years of targeted agri- environment schemes Commissioned Report No. 941 Project No: 15892 Contractor: RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Year of publication: 2017 Keywords Corn bunting; agri-environment scheme; SRDP; farmland bird; monitoring; agriculture. Background The corn bunting Emberiza calandra is a farmland bird of high conservation concern across much of Europe having undergone severe population declines and range contraction in recent decades. In Scotland, populations are now restricted to four core areas – Fife, Angus, the Western Isles and Aberdeenshire/Moray. -

Nest Survival in Year-Round Breeding Tropical Red-Capped Larks

University of Groningen Nest survival in year-round breeding tropical red-capped larks Calandrella cinerea increases with higher nest abundance but decreases with higher invertebrate availability and rainfall Mwangi, Joseph; Ndithia, Henry K.; Kentie, Rosemarie; Muchai, Muchane; Tieleman, B. Irene Published in: Journal of Avian Biology DOI: 10.1111/jav.01645 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Mwangi, J., Ndithia, H. K., Kentie, R., Muchai, M., & Tieleman, B. I. (2018). Nest survival in year-round breeding tropical red-capped larks Calandrella cinerea increases with higher nest abundance but decreases with higher invertebrate availability and rainfall. Journal of Avian Biology, 49(8), [01645]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01645 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Avian Adaptation Along an Aridity Gradient. Physiology, Behavior, And

AVIAN ADAPTATION ALONG AN ARIDITY GRADIENT PHYSIOLOGY, BEHAVIOR, AND LIFE HISTORY B. Irene Tieleman This research was financially supported by Schuurman Schimmel van Outeren Stichting National Wildlife Research Center, Taif, Saudi Arabia Schure Beijerinck Popping Fonds Lay-out: Heerko Tieleman Figures: Dick Visser Photographs: Irene Tieleman © 2002 Irene Tieleman ISBN-nummer: 90-367-1726-4 Electronic version 90-367-1727-2 RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN Avian adaptation along an aridity gradient physiology, behavior, and life history Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 10 december 2002 om 13.15 uur door Bernadine Irene Tieleman geboren op 15 juni 1973 te Groningen Promotores: Prof. S. Daan Prof. J.B. Williams Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. W.R. Dawson Prof. R.H. Drent Prof. R.E. Ricklefs Contents PART I: INTRODUCTION 1. General introduction 11 2. Physiological ecology and behavior of desert birds 19 3. The adjustment of avian metabolic rates and water fluxes to desert 61 environments PART II: PHYSIOLOGY AND BEHAVIOR OF LARKS ALONG AN ARIDITY GRADIENT 4. Adaptation of metabolism and evaporative water loss along an 89 aridity gradient 5. Phenotypic variation of larks along an aridity gradient: 105 are desert birds more flexible? 6. Physiological adjustments to arid and mesic environments in larks 131 (Alaudidae) 7. Cutaneous and respiratory water loss in larks from arid and 147 mesic environments 8. Energy and water budgets of larks in a life history perspective: 165 is parental effort related to environmental aridity? PART III: PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS 9. -

Identification of Oriental Skylark

Identification of Oriental Skylark Hadoram Shirihai he Oriental Skylark Alauda gulgula (also sometimes known as Small TSkylark, Lesser Skylark or Eastern Skylark) is found across a large area of southern Asia. Eleven races were recognised by Vaurie (1959), most of which are resident in tropical Asia, but A. g. inconspicua, which breeds west to central Asia and Iran, is migratory, though its winter quarters are not known. The species has not yet been reliably recorded in Europe, although there are several recent records for Israel (see final section, and Shirihai in prep.) and it is possible that the Oriental Skylark will eventually be found in western Europe, and perhaps even Britain and Ireland. The main confusion species is Skylark A. arvensis, especially the smaller races. Given good views, however, the careful observer should not find separating them a serious problem. This paper summarises the main identification features of Oriental Skylark and its distinction from Skylark and other larks. Identification in the field In the field, Oriental Skylark resembles Skylark in coloration, but Wood- lark Lullula arborea in shape and flight. Its pointed bill is relatively long and thick, and it has a shortish tail and relatively long legs. From a distance, it might even be confused with Short-toed Calandrella brachydactyla or Lesser Short-toed Lark C. rufescens. The following are important points to observe when identifying the Oriental Skylark in the field. SILHOUETTE AND SIZE Size as Woodlark lark's. Wings rather short, primaries project- (about 16 cm in length), significantly smaller ing little, if at all, beyond tertials, unlike than nominate Skylark (18.5 cm). -

Spain – Birds and Wines of Navarra

Spain – Birds and Wines of Navarra Naturetrek Tour Report 1 - 7 May 2019 Eurasian Wryneck Spectacled Warbler Penduline Tit Dupont’s Lark Report and images compiled by Byron Palacios Naturetrek Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Spain – Birds and Wines of Navarra Tour participants: Byron Palacios (leader) with seven Naturetrek clients Introduction The contrasts of northern Spain can never be explained comprehensively; you need to experience them yourself. The dry lowlands and plains of Navarre, combined with the foothills and cragged mountainous Pyrenean woods and high meadows, offer one of the greatest birding experiences amongst one of the best wine areas of the world! From the very elusive and rare Dupont’s Lark, the enigmatic Bearded Vulture and the endemic Citril Finch, we cruised though breathtaking landscapes with their wonderful birdlife. Alongside, we enjoyed the taste of delicious wine, shared in the knowledge people who carefully produce them and who are passionate about them ... tasting them from the actual vineyards! The Birds & Wines of Navarre has proved to be an exciting tour across an unknown land which hides superb treasures yet to be discovered! Day 1 Wednesday 1st May London Standsted – Zaragoza – Burgui After a good flight, we arrived at Zaragoza airport on time and ready to start our tour. Once our minibus was sorted and ready to go, we set off, heading north towards the base of the Navarre Pyrenees, driving through breathtaking landscapes. -

Multilocus Phylogeny of the Avian Family Alaudidae (Larks) Reveals

1 Multilocus phylogeny of the avian family Alaudidae (larks) 2 reveals complex morphological evolution, non- 3 monophyletic genera and hidden species diversity 4 5 Per Alströma,b,c*, Keith N. Barnesc, Urban Olssond, F. Keith Barkere, Paulette Bloomerf, 6 Aleem Ahmed Khang, Masood Ahmed Qureshig, Alban Guillaumeth, Pierre-André Crocheti, 7 Peter G. Ryanc 8 9 a Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese 10 Academy of Sciences, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100101, P. R. China 11 b Swedish Species Information Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7007, 12 SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden 13 c Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, 14 University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa 15 d Systematics and Biodiversity, Gothenburg University, Department of Zoology, Box 463, SE- 16 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden 17 e Bell Museum of Natural History and Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, 18 University of Minnesota, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 19 f Percy FitzPatrick Institute Centre of Excellence, Department of Genetics, University of 20 Pretoria, Hatfield, 0083, South Africa 21 g Institute of Pure & Applied Biology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, 60800, Multan, 22 Pakistan 23 h Department of Biology, Trent University, DNA Building, Peterborough, ON K9J 7B8, 24 Canada 25 i CEFE/CNRS Campus du CNRS 1919, route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier, France 26 27 * Corresponding author: Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of 28 Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100101, P. R. China; E- 29 mail: [email protected] 30 1 31 ABSTRACT 32 The Alaudidae (larks) is a large family of songbirds in the superfamily Sylvioidea. -

Phenotypic Variation of Larks Along an Aridity Gradient Tieleman, BI; Williams, JB; Buschur, ME; Brown, CR

University of Groningen Phenotypic variation of larks along an aridity gradient Tieleman, BI; Williams, JB; Buschur, ME; Brown, CR Published in: Ecology DOI: 10.1890/0012-9658%282003%29084%5B1800%3APVOLAA%5D2.0.CO%3B2 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2003 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Tieleman, BI., Williams, JB., Buschur, ME., & Brown, CR. (2003). Phenotypic variation of larks along an aridity gradient: Are desert birds more flexible? Ecology, 84(7), 1800-1815. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012- 9658%282003%29084%5B1800%3APVOLAA%5D2.0.CO%3B2 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Extremadura: 15Th-17Th March 2018

Extremadura: 15th-17th March 2018 I first visited this area at the start of May 2017 and had a wonderful time exploring the area and its wildlife. So when planning this year's visit I decided that I would like to return to this area but at a different time of the year, hence mid-March. Note on birds mentioned In the daily recording the birds mentioned are those that are either Lifers (LF) or those of the greater interest. Many other birds were seen each day but while not being mentioned have been recorded and will be listed at the end of this report. Thursday 15nd March Arrived into Seville mid morning and it soon became apparent that the weather was going to be 'interesting'; one minute sunshine, the next sheets of rain. Made a couple of stops on the way, one being at Valdesalor for the Bustards. However the road through the plains was very soft and muddy from the heavy rain and so I had to retreat. Thursday 16th March: Caceres and Belen Plains A bitterly cold morning with the threat of rain. Headed down to the plains around Caceres and Belen to search for Bustards. First stop was the hide off the road to Santa Marta (39.4771, -6.19334). The bitter wind made observations difficult as it was driving straight into the hide. However got a brief glimpse of two Black-Bellied Sandgrouse before they disappearing leaving just Crested Lark, Corn Bunting and Calandra Lark to help pass the time. For a bird so big I'm not sure where it came from but a Black Vulture walked up a far field to harass a rather ill looking sheep. -

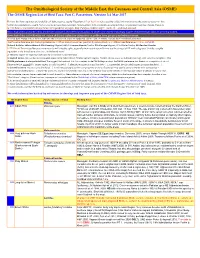

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

See the Checklist

Official Reader Rendezvous Checklist Portugal: Birding an Ancient Land Lisbon, Portugal April 2017 ü (Common) Shelduck Tadorna tadorna ü Great Bustard Otis tarda ü Mallard Anas platyrhynchos ü Little Bustard Tetrax tetrax ü Gadwall Anas strepera ü (Eurasian) Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus ü (Northern) Shoveler Anas clypeata ü (Pied) Avocet Recurvirostra avosetta ü Garganey Anas querquedula ü Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus ü (Common) Pochard Aythya ferina ü Stone Curlew Burhinus oedicnemus ü Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina ü Collared Pratincole Glareola pratincola ü Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa ü Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius ü (Common) Quail Coturnix coturnix ü (Common) Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula ü Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis ü Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus ü Great Crested Grebe Podiceps cristatus ü Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola ü Cory's Shearwater Calonectris diomedea borealis ü (Northern) Lapwing Vanellus vanellus ü Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus ü (Red) Knot Calidris canutus ü (Northern) Gannet Morus bassanus ü Sanderling Calidris alba ü (Great) Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo ü (Ruddy) Turnstone Arenaria interpres ü (European) Shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis ü Dunlin Calidris alpina ü Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus ü Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferruginea ü (Black-crowned) Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax ü Little Stint Calidris minuta ü Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis ü Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola ü Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides ü Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos