Oral History Interview with Buck Morigeau, October 26, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 17.08.2021 Anthrax Im Herbst 2022 Auf Tour In

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 17.08.2021 Anthrax im Herbst 2022 auf Tour in Deutschland Sie sind Urgesteine des Thrash-Metal und haben mittlerweile 40 Jahre Bandgeschichte auf dem Buckel. Aufhören ist deshalb aber noch lange keine Option. Anthrax nehmen stattdessen wieder Fahrt auf und haben jüngst bestätigt, dass sie im Rahmen ihres 40-jährigen Jubiläums im Herbst nächsten Jahres vier Konzerte in Deutschland spielen. "It sure has been a long time since we rock’n’rolled in the UK and Europe“, so Drummer Charlie Benante. "But we’re coming back soon to bring the noise to all of you guys. Being that we can’t get over there until 2022, we’re going to make sure that every show will be an eventful one. We won’t just be playing four decades of songs to celebrate our ongoing 40th anniversary - hey, we’ll be giving YOU some history! - but we just might have some brand new ones for you as well. Can’t wait to see all your happy, smiling faces!!!". Tief verwurzelt im Thrash-Metal, waren Anthrax Anfang der 80er maßgeblich an der Etablierung dieses Genres beteiligt. Obwohl die Band um Sänger Joey Belladonna auch heute noch zu den größten Thrash-Metal-Bands zählt und bereits vor langer Zeit Kultstatus erreichte, präsentieren sich die New Yorker Musiker – von denen Gitarrist Scott Ian als einziger noch die Ursprungsbesetzung vertritt – noch immer so experimentierfreudig wie zu ihrer Hochphase. Für ihren unverkennbaren Stil, für den sie Heavy-Metal auch gern mal mit Crossover-Elementen kombinieren, werden sie nun schon seit vier Dekaden von ihren Fans verehrt und von Kritikern stets gelobt. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Concert History of the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum

Historical Concert List updated December 9, 2020 Sorted by Artist Sorted by Chronological Order .38 Special 3/27/1981 Casting Crowns 9/29/2020 .38 Special 10/5/1986 Mitchell Tenpenny 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/17/1984 Jordan Davis 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/16/1982 Chris Janson 9/25/2020 3 Doors Down 7/9/2003 Newsboys United 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/6/2000 Mandisa 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/26/1999 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 4 Him 12/6/1996 Crowder 2/20/2020 5th Dimension 3/10/1972 Hillsong Young & Free 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 4/4/2001 Andy Mineo 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 10/24/1999 Building 429 2/20/2020 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 RED 2/20/2020 Aaron Carter 3/7/2002 Austin French 2/20/2020 Aaron Jeoffrey 8/13/1999 Newsong 2/20/2020 Aaron Tippin 5/5/1991 Riley Clemmons 2/20/2020 AC/DC 11/21/1990 Ballenger 2/20/2020 AC/DC 5/13/1988 Zauntee 2/20/2020 AC/DC 9/7/1986 KISS 2/16/2020 AC/DC 9/21/1980 David Lee Roth 2/16/2020 AC/DC 7/31/1979 Korn 2/4/2020 AC/DC 10/3/1978 Breaking Benjamin 2/4/2020 AC/DC 12/15/1977 Bones UK 2/4/2020 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 Five Finger Death Punch 12/9/2019 Addison Agen 2/8/2018 Three Days Grace 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 12/2/2002 Bad Wolves 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 11/23/1998 Fire From The Gods 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 5/17/1998 Chris Young 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 6/22/1993 Eli Young Band 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 5/29/1986 Matt Stell 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 10/3/1978 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 10/7/1977 I Prevail 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 5/25/1976 Beartooth 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 3/26/1975 Can't Swim 11/14/2019 After Seven 5/19/1991 Luke Bryan 10/23/2019 After The Fire -

Arbiter, March 22 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 3-22-2000 Arbiter, March 22 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. IItJfl JL~ lISt ZONES tEAL TH scecas 'e ARTS . ,.at::J ~ATlON j AD.flSTRA TIOO _ , ~ " SOOAL,SCENCESIH.MANTESCAAfUS HQj5J.IG --' ::; • {) • ATIt.ETlCSIEVENTS - 7/1} TECItO.OGYIE~ - 0 ~ STlaNT ~VlCES _ ? PHVSCAi. PlANT lEI •+ lNVERSlTY VlLAGf _ ' "v lNVERSTY ~.. .-# (!) ...9 o lllIl Gllllll I G f • I ~M. C " I ." _" ~ . , dJo'TI®tffi ~.~ ~~~ ~ ........ KIVI·TV '1 _ . 11ckels are $16.50 on .. now at RecordExchqe by caIIJng 1-800-9654821 or on/Ine at www.tlckelweb.com. AD ApI • Beer & WIne wIlD f) Skateworld ~.' .. -,----~-----_._-_._..__ ._- ._- . ( 'laws. Interestingly enough, Idaho remains one of the few news states that still has sodomy editor laws on its books. Viruses, robbery and jail I'm continually amazed The move was a thinly at how much slips through. veiled attempt to make' sure time. Tell me. again why our legislature without the progran1s such as "lt's Ele- spring break is so fun? knowledge of a majority of mentary" don't show upon those on campus. -

Skyler Osburn

Skyler Osburn “Lynch and Non-Lynch: A Cinematic Engagement with Process Philosophies East and West” English and Philosophy – Oklahoma State University Honors Thesis 1 Introduction I have envisioned what follows as, primarily, a work of comparative philosophy. My understanding of the sense of ‘philosophy’ extends beyond the accepted foundational works of logic, epistemology, and metaphysics, to include psychoanalytical frameworks, as well as aesthetic theories and their aesthetic objects. Whether thinking it or living it, and regardless of its particular effects, philosophy is a fundamentally creative endeavor, so artistic processes especially have a natural place alongside any mode of analytical reasoning. Given these premises, readers of this essay should not expect to find any thorough arguments as to why a given filmmaker might need to be approached philosophically. This project simply accepts that the filmmaker at hand does philosophy, and it intends to characterize said philosophy by explicating complementary figures and paradigms and then reading particular films accordingly. Furthermore, given the comparative nature of the overall project, it might be best to make an attempt at disposing of our presuppositions regarding the primacy of the argumentative as such. In what follows, there are certainly critical moments and movements; for instance, the essay’s very first section attempts to (briefly and incompletely) deconstruct Sartre’s dualistic ontology. Nevertheless, these negative interventions are incidental to a project which is meant to be primarily positive and serve as a speculatively affirmative account of David Lynch’s film- philosophical explorations. The essay that follows is split unevenly into two chapters or divisions, but the fundamental worldview developed throughout its course necessitates the equally fundamental interdependence of their specific conceptualizations. -

ONE-SHEET New England USA Leaving Eden’S Music in the Movies/TV Series

ONE-SHEET New England USA Leaving Eden’s music in the movies/TV series. Movie Director: Massimiliano Cerchi: VID: “Out of the Ashes” Leaving Eden has toured the USA, ROCK/ACOUSTIC/POP/METAL Featured in "LOCKDOWN" UK & Canada sharing the stage with Dark Star Records VID: “SKIES OF GREY” hundreds of the biggest national Sony/Universal From Leaving Eden Live DVD bands in the world including; 10 Worldwide Distribution Featured in "Maday" Years, 10 Years After (Woodstock Contact: Blu-ray and DVD Worldwide https://leavingeden.com Reunion), Adelitas Way, Alice DVD: “Leaving Eden Live Leaving Eden latest Albums Cooper, Alice In Chains, Anthrax, Xtreme Rockumentary” Apocalyptic Review (featuring VID: “Maniac” members of Godsmack), Avenged From Leaving Eden Sevenfold, Big Brother and The Documentary Holding Company (Woodstock SGL Entertainment/Dark Star Reunion), Black Sabbath (Heaven & Records/Sony Music "NO SOUL" is Featured in the Hell), Blackstone Cherry, Bret Movie/TV Series "Jezebeth" Michaels, Buckcherry, Chevelle, Written/Directed by Collective Soul, Country Joe Damien Dante (Woodstock Reunion), Damage Plan, Featured in Movie "Bloodthirst" (Featuring Dimebag & Vinnie Paul) Featured in THE NITWIT Days Of The New, Disturbed, Dope, OFFICIAL MOVIE TEASER Dropkick Murphy's, Drowning Pool, VID: "Dream With Me" Video (in Five Finger Death Punch, Fuel, a time of the CoronaVirus) By Gemini Syndrome, Gin Blossoms, Leaving Eden Godsmack, Halestorm, HELLYEAH, VID: “JAILBREAK” Herman Rarebell (The Scorpions), VID: THE AGONY OF Hinder, Hookers & Blow (featuring AFFLICTION members of Guns ‘N' Roses, Quiet VID: House of the Rising Sun Leaving Eden Touring USA, UK Riot, W.A.S.P.), In This Moment, Official Video By Leaving Eden and Canada. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

STATE of BLACK OREGON 2015 © Urban League of Portland Text © 2015 Urban League of Portland Artwork © Individual Artists

STATE OF BLACK OREGON 2015 © Urban League of Portland Text © 2015 Urban League of Portland Artwork © Individual Artists First Published in the United States of America in 2015 by the Urban League of Portland 10 North Russell Street Portland, OR 97227 Phone: (503) 280-2600 www.ulpdx.org All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the copyright owners. All images in this book have been reproduced with the knowledge and prior consent of the artists concerned, and no responsibility is accepted by the producer, publisher or printer for any infringement of copyright, or otherwise, arising from the contents of this publication. Every effort has been made to ensure that credits accurately comply with information supplied. We apologize for any inaccuracies that may have occurred and will resolve inaccurate or missing information in a subsequent reprinting of the book. Digital edition published in 2015 Photography: Intisar Abioto: www.intisarabioto.com Harold Hutchinson, HH Click Photography Dawn Jones Redstone, Hearts+Sparks Productions Design: Brenna King: www.brennaking.com Additional Design: Jason Petz, Brink Communications Jan Meyer, Meyer Creative FOREWORD The State of Black Oregon 2015 provides a clear, all people can share in the wealth of the earth. urgent call and path forward for a Black Oregon In The Beloved Community, poverty, hunger policy agenda. The report captures dreams that and homelessness will not be tolerated because have been lost and deferred. It tells us what international standards of human decency will we must do to make dreams real and inclusive not allow it. -

Upon Greeting, the Name Five Finger Death Punch

By Ray Van Horn, Jr. frosh about Moody and his comrades of chaos, which is what accounted for Five Finger Death pon greeting, the name Five Finger Death Punch Punch’s instant endearment to Korn’s devoted flock. “Although we are a bit heavier than Korn, their calls to mind Saturday afternoons and locally fans accepted us with open arms,” Moody dotes happily. “When you are playing in front of anywhere televised Kung Fu Theaters filled with chop sockey between 10 - 20,000 people a night, let’s just say, it doesn’t hurt the ego. Jon Davis and the Korn beat-em-up flicks starring Bruce Lee, Bruce Li, family were so stellar to us! They treated us as if USonny Chiba and even a young Jackie Chan and Samo Hung. we were family. Jon gave me advice on things I had no concept of, and when you open for powerhouse For those following the Nintendo generation, Five Finger bands like Korn and Vinnie Paul of Hell Yeah, you’d better bring your A game, or just throw the towel in Death Punch rings like the logical successor to Tekken and before you get spanked!” For Ivan Moody, the here is now and Motograter Mortal Kombat, a wickedly-titled video game filled with gory is, for all intents and purposes, a “sensitive subject” with him. As one of the many victims of the mayhem and metahuman martial arts moves even the most publicized Elektra Records collapse, Motograter’s final stint came through self-financed tours with dexterous of humans couldn’t possibly pull off. -

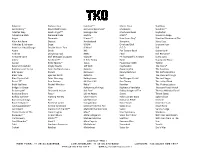

207 096 1917 FAX:(310) 913-1517 EMAIL:[email protected] »

9electric Darkest Hour Headcat** Motor Sister Skid Row Ace Frehley** Dave MacPherson Heaven’s Basement* Mudvayne Skindred** Adelitas Way Death Angel** Heavygrinder Mushroomhead Skyharbor Adrenaline Mob Diamond Plate Hed PE MXPX* Slaves On Dope Aeges Diamante Hinder** New Years Day* Slim Jim Phantom of The Alien Ant Farm Diecast Hoobastank Nonpoint Stray Cats Altitudes & Attitude Dope IDIOM One Eyed Doll Snocore Tour American Head Charge Double Vision Tour Ill Nino* P.O.D Soil Angra Doyle INC. Pat Travers Band Spineshank* Anthrax Drowning Pool INME Pearl Still Remains* Armored Saint Duff McKagan’s Loaded Islander Phil Campbell’s All Starr Sumo Cyco Ashes Earthtone9* It Dies Today Band Superjoint Ritual Avatar Eddie Money* Janus Powerman 5000 Tantric Beyond Threshold Empty Hearts Jeff Gutt Psychostick The Ataris* Bachman and Turner Even the Dead Love a Kaleido Queensrÿche The Bosshoss Billy Squier Parade Karnivool Randy Bachman The Coffis Brothers Black Tide Eyes Set to Kill Katastro RED The Damned Things Blue Öyster Cult Fates Warning Kelley James Red Dragon Cartel The Last Vegas Breed 77* Fear Factory Kill Devil Hill Rev Theory The Letter Black Brett Scallions Fireball Ministry Kittie** Revoker The Missing Letters Bridge To Grace Flaw Kottonmouth Kings Righteous Vendetta Thousand Foot Krutch Brokencyde* Flotsam & Jetsam Kris Roe* Robby Krieger of The Thomas Nicholas Band* Buck and Evans Fozzy* Life of Agony Doors Threat Signal Buffalo Summer Framing Hanley Like A Storm Robin Zander Band Ugly Kid Joe Burton Cummings Fuel Like Monroe Romantic -

February 1999

alpha tech C 0 M P ·UTE R 5 671-2334 2300 James St. Bellingham, WA 98225 www.alphatechcomputers.com Cream Ware transforms ~our Winaows PC into ani~n ~ertormance, multitracK ai~ital auaio recorain~, eaitin~ ana masterin~ worKstation witn ultra fast ~. ~·bit Si~nal ~rOC9SSin~ Ca~acit~. Desi~nea lor com~lete ai~ital music ~roaution, CreamWare consists ol ootn naraware ana its own versatile auaio wo~station software· offenn~ acom~lete solution, not just a~artial ste~. Eait mulntrac~ arran~ements on ~our nara arive witn CreamWare · rrom 2to 12~ trac~s ana more ae~enain~ on ~our PC/CreamWare con~~uration. Process effects to trac~s ana sauna files !rom aso~nisticatea suite ol Pentium oasea DSP ~lters ana effects, re~lacin~ rac~s ol ex~ensive outooara ~ear, all in real time witn no wa~in~ lor tne s~stem to calculate ana a~~~~. rull~ automatea mixin~ tnat incluaes: volume curves, cross laaes, unlimrrea non~estrucnve eaitin~ ana almost an~nin~ else ~ou've ever areamea aoout navin~ at ~our ais~osal at ONE TENTH THE COST , ~our own cas! creamw@re© • 4in /4 out (32 tracks apporx. ) • 16 in /16 out (64 tracks approx.) • Optical, S/PDIF &MIDI I/O • 2ADAT Optical, ADAT 9-pin Sync, BNC, $225 50 $14Q.gQnth 161\0 ND DIA Converter TRS, Monitor Out 'per month • Wave Walkers DSP Suite • WaveWalkers, FireWalkers DSP Suites & • Near Field Monitors w/ Apmlifier Osiris DSP I Mastering I Finalizing Suite • 12 Channel Mixer/Microphone Preamplifier • Mid Field Monitors w/ Apmlifier • Merit Pentium 11266 MidTower ·64MB RAM •8.4GB Hard Drive • 16/32 Channel Recording Console w/lnline Monitor 36x CDROM ·16x4x4 CDRW, 56k Modem -8MB Video RAM • Merit Pentium 11266 MidTower ·128MB RAM ·10.2GB Hard Drive 40x CDROM ·16x4x4 CDRW · 56k Modem- 8MB Video RAM 15" SVGA, Win 98 · MS Works 17' SVGA, Win 98 · MS Works ._...