Towards an Alternative to Neo-Liberalism: Class, Institutional and Organizational Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To: <[email protected]>

From: "Sheri Herndon" <[email protected]> To: <[email protected]> X-Priority: 3 Message-ID: <r02000200-1034-39844466DD9611D8AA3C000A95AC8380@[10.0.1.2]> MIME-Version: 1.0 Content-Type: text/plain; charset="US-ASCII" Content-Transfer-Encoding: 7bit X-Mailer: Mailsmith 2.0.2 (Blindsider) X-MailScanner: Found to be clean X-Spam-Status: not spam, SpamAssassin (score=-6.398, required 6,autolearn=not spam, AWL 0.00, BAYES_00 -4.90, FROM_ORG -3.00,RCVD_NUMERIC_HELO 1.50) X-Loop: [email protected] X-Sequence: 28 Errors-To: [email protected] Precedence: bulk X-No-Archive: yes List-Id: <discussion.lists.nwsocialforum.org> List-Help: <mailto:[email protected]?subject=help> List-Subscribe: <mailto:[email protected]?subject=subscribe%20discussion> List-Unsubscribe: <mailto:[email protected]?subject=unsubscribe%20discussion> List-Post: <mailto:[email protected]> List-Owner: <mailto:[email protected]> List-Archive: <http://lists.nwsocialforum.org/lists/arc/discussion> Subject: [discussion] Fwd: What Exactly Is a Social Forum? X-Uwash-Spam: Gauge=IIIIIII, Probability=7%, Report='EXCUSE_3 0.001, __HAS_X_PRIORITY 0, __HAS_MSGID 0, __SANE_MSGID 0, __MIME_VERSION 0, __EVITE_CTYPE 0, __CT_TEXT_PLAIN 0, __CT 0, __CTE 0, __HAS_X_MAILER 0, __SOBIG_X_MAILSCANNER 0, __X_MAIL_SCANNER 0, __HAS_X_LOOP 0, X_LOOP 0, FWD_MSG 0, TO_BE_REMOVED_REPLY 0.000, __TO_MALFORMED_2 0, file:///Users/tom%20collicott/Desktop/discussion-list-archive.txt[11/6/20, 4:00:53 PM] REMOVE_FROM_LIST 0.000, __MIME_TEXT_ONLY 0' ====== Forwarded Message ====== Date: 7/24/04 10:14 AM Received: 7/24/04 5:16 PM -0000 From: [email protected] (The Nation Magazine) To: [email protected] Dear EmailNation Subscriber, Kicking off last night, the Boston Social Forum is the foremost gathering of progressives in Boston this week as the Democrats assemble at the Fleet Center for their convention. -

THE GLOBAL SOCIAL FORUM MOVEMENT Michael Menser

THE GLOBAL SOCIAL FORUM MOVEMENT Michael Menser PORTO ALEGRE’S “PARTICIPATORY BUDGET,” AND THE MAXIMIZATION OF DEMOCRACY INTRODUCTION COUNTER-HEGEMONIC GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEMOCRATIC IMPULSE The World Social Forum is a new social and political phenomenon. The fact that it does have antecedents does not diminish its new- ness. Rather, quite the opposite. It is not an event, nor a mere suc- cession of events. It is not a scholarly conference, although the contributions of many scholars converge in it. It is not a party or an international of parties, although militants and activists of many parties all over the world take part in it. It is not an NGO [non-gov- ernmental organization] or confederation of NGOs, even though its conception and organization owes a great deal to them. It is not a social movement, even though it often designates itself as a move- ment of movements. Although it presents itself as an agent of social change, the WSF rejects the concept of a historical subject and confers no priority on any specific social actor in the process of social change. It holds no clearly defined ideology either in defin- ing what it rejects or what it asserts. (Santos 2003, 235) The possibility of democracy on a global scale is emerging today for the very first time. (Hardt and Negri 2004 xi) HROUGHOUT THE 1990S, the fragmentation of the US and global Left inspired as much ridicule as it did critical analysis. A seemingly Tinfinite series of splits occurred along a variety of axes: ethnic and racial identity, geographical place, sexual orientation/practices, organization type, lifestyle choice, relationships with nonhumans, degree of ideological purity, and on and on. -

Feasibility Report World Peace Forum 2006

Feasibility Report World Peace Forum 2006 Prepared For: March 13 2005 Prepared by: City Manager IdeaWorks Consulting Inc City of Vancouver Casper Communications Contents INTRODUCTION 3 BACKGROUND 3 ORGANIZING STRUCTURE ............................................................................. 3 EVENT STRUCTURE....................................................................................... 4 VENUES ........................................................................................................ 5 BUDGET AND ECONOMIC BENEFITS.............................................................. 5 Funding Strategy...................................................................................... 5 Economic Benefits.................................................................................... 6 FEASIBILITY STUDY QUESTIONS 6 An assessment of the feasibility of the proposed format, duration and theme as adopted at the preparatory conference being held November 26 and 27, 2004. ................................................... 6 An assessment of the interest at the national and international level in supporting and participating in such an event........................... 8 An analysis of the budget necessary for the proposed event and identification of possible sources of sponsorship and partnership from the non-profit and private sectors to achieve the budget............................................................................... 9 Recommendations on whether the City should be involved in holding the Peace Forum, -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE George Katsiaficas [email protected] http://eroseffect.com Education: Ph.D. Sociology 1983 University of California, San Diego M.A. Sociology 1976 University of California, San Diego B.S. Management 1970 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Doctoral Studies: Philosophy and Social Science 1979-81 Free University of Berlin, Germany Academic Positions: Professor 1990-2015 Wentworth Institute of Technology Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Visiting Professor 2001-2; 2007-2009; 2016 Chonnam National University, Gwangju, South Korea May 18 Institute, Department of Sociology Associate in Research 2006-2008 Harvard University Korea Institute Visiting Scholar and Faculty Affiliate 1993-4 Harvard University Center for European Studies Visiting Lecturer 1986, 1989 Tufts University Department of Sociology Teaching Assistant 1969-70 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management Graduate Program Areas of Specialization: Social Movements Asian Politics US Foreign Policy Comparative Global Studies George Katsiaficas Curriculum Vitae Language Proficiencies: English German (excellent) Spanish (good) French, Greek, Korean (basic) Honors and Awards: Kim Dae-jung Scholar’s Award (Hu-Kwang Award), Chonnam National University, May 2016 Honorary Citizen, City of Gwangju, South Korea, 2016 Charles A. McCoy Career Achievement Award for a progressive political scientist who has had a long career as a writer, teacher and activist presented by the Section for a New Political Science of the American Political Science Association in Seattle, September 2011. Award for Outstanding Service from the May Mothers’ House (widows and mothers of people killed in the 1980 uprising for democracy in Gwangju, South Korea) on May 8, 2010. International Visiting Fellowship, Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, 2009. -

The United States Social Forum: Perspectives of a Movement

The United States Social Forum: Perspectives of a Movement Edited by: The USSF Book Committee Marina Karides Sociologists Without Borders Florida Atlantic University Walda Katz-Fishman Project South: Institute for the Elimination of Poverty & Genocide Howard University Rose M. Brewer scholar activist University of Minnesota-TC AfroEco Alice Lovelace Lead Staff Organizer, 2007 USSF Associate Regional Director SERO American Friends Service Committee Jerome Scott Project South: Institute for the Elimination of Poverty & Genocide @USSF Book Committee 2010 ISBN ############# Changemaker Publications Chicago IL USA http://stores.lulu.com/changemaker For those who struggled through Katrina and continue to this day; and for all of us who together are building another world Katrina is both a reality and a symbol. It is of course the most egre- gious human right violation that is ongoing right now. But it is also a symbol, that basically what we heard today, what we are reminded of, is that there is Katrinas all over this country. That if you are workin’ in the field of criminal justice, you are talkin’ about Katrina; if you are workin’ on healthcare, you are talkin’ about Katrina; if you are workin’ on hous- ing, you are talkin’ about Katrina; we are living a Katrina nightmare here in this country. All of us who are living this Katrina nightmare we have to name the source of it. And the source of it is this backward, racist capitalist sys- tem. Understand this my friends, we have to remind ourselves to under- stand, it’s really about us the people, we have to organize ourselves, we have to affect a shift in power, because the only way to have human rights accountability is when the people are organized. -

Participatory Democracy in the Bolivarian Revolution

1 Feminists Weaving Together Theory And Praxis: Participatory Democracy in the Bolivarian Revolution 2 From the Boston Social Forum to the VI World Social Forum in Caracas I attended the Boston social forum in the summer of 2004 before the Democratic Convention began. At that time I had little idea of its origins and its significance both to myself and to the world. I went as a curious observer and became a participant in the Women’s Tribunal Against Violence sponsored by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and other women’s groups. Four of us shared our stories about violence with a small limited audience. Later that evening the “wise women” who listened issued their verdict: violence against women was a systemic occurrence which was largely unacknowledged and treated in our society as personal wrongs. As a faculty member at University of Massachusetts I had taught about gender violence. Now I was an insider telling my own story, integrating theory and praxis. When I heard there would be a VI world social forum in Caracas, Venezuela two years later in January of 2006 I signed up to be part of a self-appointed Boston delegation. I spent two weeks in Venezuela, as a participant observer. I have a particular interest in Latin cultures and have traveled and lived in this part of the world. In 1961 I spent three weeks with an Antioch student group observing the early stages of the Cuban revolution. Through the 70s-and early 90s I was part of the Guatemala committee in Boston working to support the Guatemala refugees. -

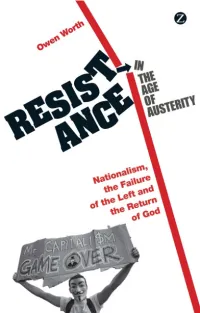

Resistance in the Age of Austerity Nationalism, the Failure of the Left and the Return of God

About the author Owen Worth is a lecturer in international relations at the University of Limerick, Ireland. He has published widely in the areas of global political economy and in particular in the areas of globalization, hegemony and resistance. He is the author of Hegemony, International Political Economy and Post-Communist Russia (2005), and he co-edited European Regionalism and the Left (with Gerry Strange, 2012), Globlisation and the ‘New’ Semi-Peripheries (with Phoebe Moore, 2009) and Criti- cal Perspectives on International Political Economy (with Jason Abbott, 2002). He has published work on resist- ance and globalization in Global Society, Global izations, Capital and Class and Third World Quarterly, and has also published in International Politics, Review of Inter- national Studies and Journal of International Relations and Development. He is the current managing editor of Capital and Class and is on the executive board of the Conference of Socialist Economics. RESISTANCE IN THE AGE OF AUSTERITY NATIONALISM, THE FAILURE OF THE LEFT AND THE RETURN OF GOD Owen Worth Fernwood Publishing halifax | winnipeg Zed Books london | new York Resistance in the age of austerity: nationalism, the failure of the left and the return of God was first published in 2013 by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London n1 9jf, uk and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, ny 10010, usa www.zedbooks.co.uk Copyright © Owen Worth 2013 The right of Owen Worth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Set in ffKievit and Monotype Plantin by Ewan Smith, London Index: [email protected] Cover design: www.rawshock.co.uk Cover photo © iStock All rights reserved. -

European Social Forum London 14-17 October 2004 Coates.Qxd 8/27/04 7:21 AM Page 33

Genefke 8/27/04 7:20 AM Page 31 European Social Forum London 14-17 October 2004 Coates.qxd 8/27/04 7:21 AM Page 33 33 Another The European Social Forum was inspired by the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre. This World Is defined itself in distinction from the World Possible Economic Forum at Davos, which took on its shoulders all the sins of neo-liberalism with the globalisation of greed. An impressive list of The European participants has been assembled from non- Social Forum governmental organisations in a wide variety of Comes to London countries. Now the European Social Forum will come to London, at the invitation of a number of activist groupings, with the support of Ken Coates London Mayor, Ken Livingstone. We are bound to wish it well, because there is a great vacuum where consequent political discussion used to take place, and there are many urgent social issues about which informed people need to share their experiences. It remains to be seen how widely the Social Forum will be able to cast its net, when it comes to England. In several European countries at the same time, there are a number of key problems which would clearly benefit from joint analysis, and if it could be achieved, common action. It is not difficult to see why the European Social Forums have established a prototype for this kind of convergence. Basing themselves on the traditions, and the Charter of Principles agreed by the World Social Forum (see p.38), which met in Porto Alegre, Brazil, the European Social Forum met first of all in Florence, and then, last year, in Paris. -

Note from the Editors Blau

Societies Without Borders Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 1 2008 Note from the Editors Blau Alberto Moncada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Blau & Alberto Moncada. 2009. "Note from the Editors." Societies Without Borders 3 (1): 1-3. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol3/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Blau and Moncada: Note from the Editors Societies Without Borders Published by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons, 2009 1 Societies Without Borders, Vol. 3, Iss. 1 [2009], Art. 1 Societies Without Borders Aims & Scope Societies Without Borders is a bi-annual journal, co-edited by Judith Blau and Alberto Moncada. One of the main ideas behind Societies Without Borders is bringing scholars from different continents closer together by showing their different approaches of the same research material, especially human rights and public goods. Many scholars from developing countries, paradoxi- cally, have utopian ideas that they pursue, whereas progressive US scholars, for example, are more engaged in criticism. Societies Without Borders aims at bridging this gap; the journal also aims at breaking down the walls between the disciplines of Social Sciences, Human Rights (as formulated in the international standards of the UN-related organizations), Environmental Sciences, and the Humanities. -

The Liberty Tree Foundation for the Democratic Revolution at 10

Democracy Is Coming to the U.S.A. The Liberty Tree Foundation for the Democratic Revolution at 10 Years Our Vision The Liberty Tree Foundation for the Democratic Revolution is a nonprofit organization rooted in the belief that the American Revolution is a living tradition whose greatest promise is democracy. In order to achieve that promise, Liberty Tree works to create a society in which communities and individuals have the desire, skills, and capacity to participate in the vital decisions that affect their lives. Such a society, we believe, is most likely to emerge from a genuine democratic revolution -- one that focuses on deep structural, legal, and institutional change, dismantles oppression in all its forms, and is organized through the transformation of communities, institutions and local governments into conscious agents of democratic change. The Original Liberty Tree Our Mission Liberty Tree is uniquely committed to building a democracy movement for the U.S.A.. We provide The first, famous Liberty Tree stood on the Boston Common, an American Elm with a political vital support to grassroots campaigns for democratic reform in many areas of American life, and history. The elm was a commons tree in the pre-Norman ‘English borough’ tradition: A place for bring those campaigns together to form a united movement for democracy. the people of the shire to gather on their own terms and for their own purposes. In the decade of agitation that fed into the American Revolution, Boston radicals rallied beneath the tree’s canopy, speaking against imperial authorities and calling for home rule in the colonies. -

Solidarity Economy: Building Alternatives for People and Planet

SOLIDARITY ECONOMY: BUILDING ALTERNATIVES FOR PEOPLE AND PLANET PAPERS AND REPORTS FROM THE U.S. SOCIAL FORUM 2007 Edited by Jenna Allard, Carl Davidson, and Julie Matthaei ChangeMaker Publications Chicago IL USA Copyright © 2008, U.S. Solidarity Economy Network All rights reserved ORDERING INFORMATION For individual copies, order online from ChangeMaker Publications, Chicago IL USA, www.lulu.com/changemaker For bulk orders, special discounts may be available. Contact Germai Medhanie at Guramylay: Growing the Green Economy, [email protected], 617-868-6133. For college textbook orders, or orders by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesal- ers contact Germai Medhanie at Guramylay: Growing the Green Economy, [email protected], 617-868-6133. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-6151-9489-9 Globe Cover Graphic: Tiffany Sankary, www.movementbuilding.org/tiffany Cover Design: Carl Davidson To Father Jose Maria Arizmendi (1915-1976) who thought deeply, put human solidarity first, made tools our servants rather than the reverse, and together with his students, brought the Mondragon cooperatives into this world, to blaze a path forward To Alice Lovelace and the other organizers of the U.S. Social Forum 2007 for making this all possible To the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network, may it thrive and grow And to the second superpower the millions of people around the globe who are bringing about a better world for us all About Our Editors Jenna Allard is an editor of TransformationCentral.org, and works for Guramylay: Growing the Green Economy. She is also part of the Coordinating Committee for the U.S. -

Are Social Forums the Future of Social Movements?

Blackwell Publishing Ltd.Oxford, UK and Malden, USAIJURInternational Journal of Urban and Regional Research0309-13172005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.June 200529241724 Debates and DevelopmentsDebates and DevelopmentsDebate Volume 29.2 June 2005 417–24 International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Are Social Forums the Future of Social Movements? PETER MARCUSE A century ago, class issues seemed to be the organizing focus of progressive struggles in most of the world. Since the end of the second world war, the terrain of struggle seems to have changed: anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, identity issues including ethnic, racial, gender issues, and urban social mobilizations around ‘collective consumption’, which might include everything from anti-urban renewal, anti-displacement, anti- gentrification, anti-privatization and public service issues, and more recently alternative- globalization1 protests, have all at various times seemed the successor to class struggles — although class continued to play a key role in many of them. Some of the literature (e.g. Castells) focused the discussion on ‘urban’ movements, although redefining that term; world-wide, progressive struggles today are at least as much rurally-based, if with urban connections, as they are city-oriented. If ‘urban’ is considered in the sense Castells (1972) put it forward, as the sphere of collective consumption, it would indeed remain a central component of progressive struggles; but then it would also need to be linked to issues in the sphere of production. Are social forums, in the line begun with the first World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, picking up on the Seattle protest of 1999, the successor and culmination of these struggles? (We should be clear that the ‘forums’ sponsored by the United Nations, e.g.