Melungeon Literacies and 21St Century Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

African American Culture

g e n e r a l i n f o r m a t i o n ν Most African-Americans are Christians of various denominations, such as Episcopal and Methodist or a combination of the two. They are also Baptist, Lutheran and he following information is provided to help Catholics as well as a number of Tyou become more aware of your patients’ and Pentecostals and Jehovah’s Witnesses. coworkers’ views, traditions, and actions. While you can use this information as a guide, ν African-Americans are a mainstay in the American entertainment culture in such keep in mind that all people within a culture fields as professional sports, cinema, are not the same. Be sure to ask your patients journalism and music. and their families about specific beliefs, practices, and customs that may be relevant ν You should address the patient in a and important during medical treatment and courteous manner. All people, without hospitalization. regard to culture, race, gender and disability, want to be treated with respect When describing the African-American culture, and courtesy. the following information could apply to African-Americans from all of the states, as ν Although most African-Americans were well as some African-Americans living outside born in the United States, a sizable of the United States. Each piece of number have come from such African information does not necessarily apply to all countries like: Nigeria, and Zaire/Congo. people of African-American descent. i n t e r - p e r s o n a l r e l a t i o n s h i p s relationship roles personal space ν Religion and extended family are traditionally ν Many African-Americans are outspoken, and very important among African-Americans. -

1 Educational and Labor Market Outcomes of Ghanaian, Liberian

Educational and labor market outcomes of Ghanaian, Liberian, Nigerian, and Sierra Leonean Americans, 2010–2017 Ernesto F. L. Amaral Texas A&M University, [email protected] Arthur Sakamoto Texas A&M University, [email protected] Courtney Nelson Sweet Briar College, [email protected] Sharron X. Wang Texas A&M University, [email protected] Abstract Research on immigrant African Americans is slowly increasing, but more studies are needed particularly in regard to specific ethnic groups and their second-generation offspring. We investigate socioeconomic outcomes among second-generation African Americans focusing on those from English-speaking countries in West Africa including Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone (GLNS). We use data from the 2010–2017 Current Population Surveys to impute ethnicity on the basis of country of parental birth. Results for generalized ordered logit models for men reveal that GLNS are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than third-plus-generation whites, third-plus-generation blacks, second-generation whites, other-second-generation blacks, but not second-generation Asians. Among women, GLNS are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than all of these groups. OLS estimates of regressions of wages show that net of education, age, marital status, and having children, GLNS men are not disadvantaged relative to third-plus-generation whites in contrast to the disadvantage of 7 percent for other-second- generation blacks and 18 percent for third-plus-generation blacks. In regard to women, neither GLNS nor other-second-generation blacks are disadvantaged relative to third-plus-generation whites in contrast to the disadvantage of 8 percent for third-plus-generation blacks. -

Puerto Ricans at the Dawn of the New Millennium

puerto Ricans at the Dawn of New Millennium The Stories I Read to the Children Selected, Edited and Biographical Introduction by Lisa Sánchez González The Stories I Read to the Children documents, for the very first time, Pura Belpré’s contributions to North Puerto Ricans at American, Caribbean, and Latin American literary and library history. Thoroughly researched but clearly written, this study is scholarship that is also accessible to general readers, students, and teachers. Pura Belpré (1899-1982) is one of the most important public intellectuals in the history of the Puerto Rican diaspora. A children’s librarian, author, folklorist, translator, storyteller, and puppeteer who began her career the Dawn of the during the Harlem Renaissance and the formative decades of The New York Public Library, Belpré is also the earliest known Afro-Caribeña contributor to American literature. Soy Gilberto Gerena Valentín: New Millennium memorias de un puertorriqueño en Nueva York Edición de Carlos Rodríguez Fraticelli Gilberto Gerena Valentín es uno de los personajes claves en el desarrollo de la comunidad puertorriqueña Edwin Meléndez and Carlos Vargas-Ramos, Editors en Nueva York. Gerena Valentín participó activamente en la fundación y desarrollo de las principales organizaciones puertorriqueñas de la postguerra, incluyendo el Congreso de Pueblos, el Desfile Puertorriqueño, la Asociación Nacional Puertorriqueña de Derechos Civiles, la Fiesta Folclórica Puertorriqueña y el Proyecto Puertorriqueño de Desarrollo Comunitario. Durante este periodo también fue líder sindical y comunitario, Comisionado de Derechos Humanos y concejal de la Ciudad de Nueva York. En sus memorias, Gilberto Gerena Valentín nos lleva al centro de las continuas luchas sindicales, políticas, sociales y culturales que los puertorriqueños fraguaron en Nueva York durante el periodo de a Gran Migracíón hasta los años setenta. -

Topography Along the Virginia-Kentucky Border

Preface: Topography along the Virginia-Kentucky border. It took a long time for the Appalachian Mountain range to attain its present appearance, but no one was counting. Outcrops found at the base of Pine Mountain are Devonian rock, dating back 400 million years. But the rocks picked off the ground around Lexington, Kentucky, are even older; this limestone is from the Cambrian period, about 600 million years old. It is the same type and age rock found near the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Of course, a mountain range is not created in a year or two. It took them about 400 years to obtain their character, and the Appalachian range has a lot of character. Geologists tell us this range extends from Alabama into Canada, and separates the plains of the eastern seaboard from the low-lying valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Some subdivide the Appalachians into the Piedmont Province, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge area, and the Appalachian plateau. We also learn that during the Paleozoic era, the site of this mountain range was nothing more than a shallow sea; but during this time, as sediments built up, and the bottom of the sea sank. The hinge line between the area sinking, and the area being uplifted seems to have shifted gradually westward. At the end of the Paleozoric era, the earth movement are said to have reversed, at which time the horizontal layers of the rock were uplifted and folded, and for the next 200 million years the land was eroded, which provided material to cover the surrounding areas, including the coastal plain. -

Description of the Estillville Sheet

DESCRIPTION OF THE ESTILLVILLE SHEET. GEOGRAPHY. ward across the States of Illinois and Indiana. course to the Ohio. South of Chattanooga the ment among the high points on Wallin Ridge, the Its eastern boundary is sharply defined by the streams flow directly to the Gulf of Mexico. even crest of Stone Mountain, and the summit of General relations. The territory represented Alleghany front and ..the Cumberland escarp Topography of the Appalachian province. The Powell Mountain west of Slemp Gap. Beyond by the Estillville atlas sheet is one-quarter of a ment. The rocks of this division are almost different divisions of the province vary much in Big Black Mountain, with its irregular crest, is square degree of the earth's surface, extending entirely of sedimentary origin, and remain very character of topography, as do also different por the even summit of Pine Mountain, planed down from latitude 36° 30' on the south to 37° on the nearly horizontal. The character of the surface, tions of the same division. This variation of top to the general height of the valley ridges. The north, and from longitude 82° 30' on the east to which is dependent on the character and attitude ographic forms is due to several conditions, which peneplain was originally very nearly horizontal, 83° on the west. Its average width is 27.7 miles, of the rocks, is that of a plateau more or less com either prevail at present or have prevailed in the but it has been tilted, so that now it varies in ele its length is 34.5 miles, and its area is 956.6 pletely worn down. -

How Did the Civil Rights Movement Impact the Lives of African Americans?

Grade 4: Unit 6 How did the Civil Rights Movement impact the lives of African Americans? This instructional task engages students in content related to the following grade-level expectations: • 4.1.41 Produce clear and coherent writing to: o compare and contrast past and present viewpoints on a given historical topic o conduct simple research summarize actions/events and explain significance Content o o differentiate between the 5 regions of the United States • 4.1.7 Summarize primary resources and explain their historical importance • 4.7.1 Identify and summarize significant changes that have been made to the United States Constitution through the amendment process • 4.8.4 Explain how good citizenship can solve a current issue This instructional task asks students to explain the impact of the Civil Rights Movement on African Claims Americans. This instructional task helps students explore and develop claims around the content from unit 6: Unit Connection • How can good citizenship solve a current issue? (4.8.4) Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 How did the 14th What role did Plessy v. What impacts did civic How did Civil Rights Amendment guarantee Ferguson and Brown v. leaders and citizens have legislation affect the Supporting Questions equal rights to U.S. Board of Education on desegregation? lives of African citizens? impact segregation Americans? practices? Students will analyze Students will compare Students will explore how Students will the 14th Amendment to and contrast the citizens’ and civic leaders’ determine the impact determine how the impacts that Plessy v. -

The Free State of Winston"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston" Susan Neelly Deily-Swearingen University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Deily-Swearingen, Susan Neelly, "Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2444. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2444 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBEL REBELS: RACE, RESISTANCE, AND REMEMBRANCE IN THE FREE STATE OF WINSTON BY SUSAN NEELLY DEILY-SWEARINGEN B.A., Brandeis University M.A., Brown University M.A., University of New Hampshire DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May 2019 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in History by: Dissertation Director, J. William Harris, Professor of History Jason Sokol, Professor of History Cynthia Van Zandt, Associate Professor of History and History Graduate Program Director Gregory McMahon, Professor of Classics Victoria E. Bynum, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Texas State University, San Marcos On April 18, 2019 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

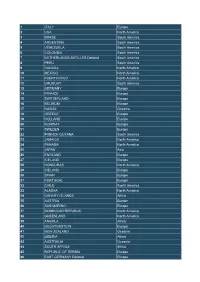

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Scotch-Irish in America. ' by Samuel, Swett Green

32 American Antiquarian Society. [April, THE SCOTCH-IRISH IN AMERICA. ' BY SAMUEL, SWETT GREEN. A TRIBUTE is due from the Puritan to the Scotch-Irishman,"-' and it is becoming in this Society, which has its headquar- ters in the heart of New England, to render that tribute. The story of the Scotsmen who swarmed across the nar- row body of water which separates Scotland from Ireland, in the seventeenth century, and who came to America in the eighteenth century, in large numbers, is of perennial inter- est. For hundreds of years before the beginning of the seventeenth centurj' the Scot had been going forth con- tinually over Europe in search of adventure and gain. A!IS a rule, says one who knows him \yell, " he turned his steps where fighting was to be had, and the pay for killing was reasonably good." ^ The English wars had made his coun- trymen poor, but they had also made them a nation of soldiers. Remember the "Scotch Archers" and the "Scotch (juardsmen " of France, and the delightful story of Quentin Durward, by Sir Walter Scott. Call to mind the " Scots Brigade," which dealt such hard blows in the contest in Holland with the splendid Spanish infantry which Parma and Spinola led, and recall the pikemen of the great Gustavus. The Scots were in the vanguard of many 'For iickiiowledgments regarding the sources of information contained in this paper, not made in footnotes, read the Bibliographical note at its end. ¡' 2 The Seotch-líiáh, as I understand the meaning of the lerm, are Scotchmen who emigrated to Ireland and such descendants of these emigrants as had not through intermarriage with the Irish proper, or others, lost their Scotch char- acteristics. -

Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1998 Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping Claudine Hoffman Truong Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Psychology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Truong, Claudine Hoffman, "Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping" (1998). Masters Theses. 1766. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1766 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied . PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university or the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I / 2 1 /fa Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.f orm Race-class Interactions in Stereotyping (TITLE) BY Claudine Hoffman Truong J lf 7~ - THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILIJNOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON. -

Delphi: a Comprehensive Suite for Delphi Software and Associated Resources Lin Li Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints Publications Physics and Astronomy 5-2012 DelPhi: A Comprehensive Suite for DelPhi Software and Associated Resources Lin Li Clemson University Chuan Li Clemson University Subhra Sarkar Clemson University Jie Zhang Clemson University Shawn Witham Clemson University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/physastro_pubs Part of the Biological and Chemical Physics Commons Recommended Citation Please use publisher's recommended citation. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics and Astronomy at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Lin Li, Chuan Li, Subhra Sarkar, Jie Zhang, Shawn Witham, Zhe Zhang, Lin Wang, Nicholas Smith, Marharyta Petukh, and Emil Alexov This article is available at TigerPrints: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/physastro_pubs/421 Li et al. BMC Biophysics 2012, 5:9 http://www.biomedcentral.com/2046-1682/5/9 SOFTWARE Open Access DelPhi: a comprehensive suite for DelPhi software and associated resources Lin Li1, Chuan Li1, Subhra Sarkar1,2, Jie Zhang1,2, Shawn Witham1, Zhe Zhang1, Lin Wang1, Nicholas Smith1, Marharyta Petukh1 and Emil Alexov1* Abstract Background: Accurate modeling of electrostatic potential and corresponding energies becomes increasingly important for understanding properties of biological macromolecules and their complexes. However, this is not an easy task due to the irregular shape of biological entities and the presence of water and mobile ions. Results: Here we report a comprehensive suite for the well-known Poisson-Boltzmann solver, DelPhi, enriched with additional features to facilitate DelPhi usage.