The Abdomen 1011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

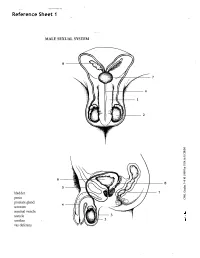

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences Journal Home Page: http://www.ijmhs.net ISSN:2277-4505 Review article Examining the liver – Revisiting an old friend Cyriac Abby Philips1*, Apurva Pande2 1Department of Hepatology and Transplant Medicine, PVS Institute of Digestive Diseases, PVS Memorial Hospital, Kaloor, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2Department of Hepatology, Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, D-1, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, India. ABSTRACT In the current era of medical practice, super saturated with investigations of choice and development of diagnostic tools, clinical examination is a lost art. In this review we briefly discuss important aspects of examination of the liver, which is much needed in decision making on investigational approach. We urge the new medical student or the newly practicing physician to develop skills in clinical examination for resourceful management of the patient. KEYWORDS: Liver, examination, clinical skills, hepatomegaly, chronic liver disease, portal hypertension, liver span INTRODUCTION respiration, the excursion of liver movement is around 2 to 3 The liver attains its adult size by the age of 15 years. The cm. Castell and Frank has elegantly described normal liver liver weighs 1.2 to 1.4 kg in women and 1.4 to 1.5 kg in span in men and women utilizing the percussion method men. The liver seldom extends more than 5 cm beyond the (Table 1). Accordingly, the mean liver span is 10.5 cm for midline towards the left costal margin. During inspiration, men and 7 cm in women. During examination, a span 2 to 3 the diaphragmatic exertion moves the liver downward with cm larger or smaller than these values is considered anterior surface rotating to the right. -

Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/Adolescent

Gastroenterology 2016;150:1456–1468 Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/ Adolescent Jeffrey S. Hyams,1,* Carlo Di Lorenzo,2,* Miguel Saps,2 Robert J. Shulman,3 Annamaria Staiano,4 and Miranda van Tilburg5 1Division of Digestive Diseases, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Connecticut Children’sMedicalCenter,Hartford, Connecticut; 2Division of Digestive Diseases, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; 3Baylor College of Medicine, Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas; 4Department of Translational Science, Section of Pediatrics, University of Naples, Federico II, Naples, Italy; and 5Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina Characterization of childhood and adolescent functional Rome III criteria emphasized that there should be “no evi- gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) has evolved during the 2- dence” for organic disease, which may have prompted a decade long Rome process now culminating in Rome IV. The focus on testing.1 In Rome IV, the phrase “no evidence of an era of diagnosing an FGID only when organic disease has inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process been excluded is waning, as we now have evidence to sup- that explain the subject’s symptoms” has been removed port symptom-based diagnosis. In child/adolescent Rome from diagnostic criteria. Instead, we include “after appro- IV, we extend this concept by removing the dictum that priate medical evaluation, the symptoms cannot be attrib- “ ” fi there was no evidence for organic disease in all de ni- uted to another medical condition.” This change permits “ tions and replacing it with after appropriate medical selective or no testing to support a positive diagnosis of an evaluation the symptoms cannot be attributed to another FGID. -

General Physical Examination Skills for Ahps

General Physical Examination Techniques for the Rheumatology Clinic This manual has been developed as an overview of the general examination of the rheumatology patient. Certain details have been specifically omitted because they have no relevance when examining a stable out patient in the rheumatology clinic. Vital Signs 1. Heart rate 2. Blood pressure 3. Weight 1. Heart Rate There are two things you want to document when assessing heart rate: The actual rate and the rhythm. Rate: count pulse for at least 15 – 30 seconds (e.g., if you count the rate for 15 seconds, multiply this result by 4 to determine heart rate). The radial pulse is most commonly used to assess the heart rate. With the pads of your index and middle fingers, compress the radial artery until a pulsation is detected. Normal 60-100 bpm Bradycardia <60 bpm Tachycardia >100 bpm 2. Heart Rhythm The rhythm should be regular. A regularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular but there is a pattern to the irregularity. For example every third beat is dropped. An irregularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular and there is no pattern to the irregularity. The classic example of this is atrial fibrillation. 3. Blood Pressure Blood pressure should be measured in both arms, and should include an assessment of orthostatic change How to measure the Brachial Artery Blood Pressure: • Patient should be relaxed, in a supine or sitting position, with the arms positioned correctly(at, not above, the level of the heart) • Remember that measurements should be taken bilaterally • Choice of appropriate cuff size for the patient is important to accuracy of measured blood pressure. -

Case Report Acute Abdomen Caused by Brucellar Hepatic Abscess

Case Report Acute Abdomen Caused by Brucellar Hepatic Abscess Cem Ibis, Atakan Sezer, Ali K. Batman, Serkan Baydar, Alper Eker,1 Ercument Unlu,2 Figen Kuloglu,1 Bilge Cakir2 and Irfan Coskun, Departments of General Surgery, 1Infectious Diseases and 2Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Trakya University, Edirne, Turkey. Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection that is transmitted from animals to humans by ingestion of infected food products, direct contact with an infected animal, or aerosol inhalation. The disease is endemic in many coun- tries, including the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, India, Mexico, Central and South America and, central and southwest Asia. Human brucellosis is a systemic infection with a wide clinical spectrum. Although hepatic involvement is very common during the course of chronic brucellosis, hepatic abscess is a very rare complication of Brucella infection. We present a case of hepatic abscess caused by Brucella, which resembled the clinical presentation of surgical acute abdomen. [Asian J Surg 2007;30(4):283–5] Key Words: acute abdomen, Brucella, brucelloma, hepatic abscess, percutaneous drainage Introduction and high fever. His symptoms began 2 days before admis- sion. For the previous 2 weeks, he suffered from a slight Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection transmitted from ani- evening fever and associated sweating. Physical examina- mals to humans by ingestion of infected food products, tion revealed moderate splenomegaly, tenderness, abdom- direct contact with an infected animal, or inhalation of inal guarding, and rebound tenderness in the right upper aerosols.1 The disease remains endemic in many coun- quadrant. The symptoms of peritoneal irritation in the tries, mainly in the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, right upper quadrant of the abdomen clinically suggested a India, Mexico, Central and South America and, currently, surgical acute abdomen. -

Utility of the Digital Rectal Examination in the Emergency Department: a Review

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1196–1204, 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.015 Clinical Reviews UTILITY OF THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT: A REVIEW Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE*† and Stephen J. Bauer, MD† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and †University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Reprint Address: Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown Veterans Hospital, 820 S Damen Ave., M/C 111, Chicago, IL 60612 , Abstract—Background: The digital rectal examination abdominal pain and acute appendicitis. Stool obtained by (DRE) has been reflexively performed to evaluate common DRE doesn’t seem to increase the false-positive rate of chief complaints in the Emergency Department without FOBTs, and the DRE correlated moderately well with anal knowing its true utility in diagnosis. Objective: Medical lit- manometric measurements in determining anal sphincter erature databases were searched for the most relevant arti- tone. Published by Elsevier Inc. cles pertaining to: the utility of the DRE in evaluating abdominal pain and acute appendicitis, the false-positive , Keywords—digital rectal; utility; review; Emergency rate of fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) from stool obtained Department; evidence-based medicine by DRE or spontaneous passage, and the correlation be- tween DRE and anal manometry in determining anal tone. Discussion: Sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria; there INTRODUCTION were two for abdominal pain, five for appendicitis, six for anal tone, and three for fecal occult blood. -

General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

General signs and symptoms of abdominal diseases Dr. Förhécz Zsolt Semmelweis University 3rd Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine, 3rd Year 2018/2019 1st Semester • For descriptive purposes, the abdomen is divided by imaginary lines crossing at the umbilicus, forming the right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower quadrants. • Another system divides the abdomen into nine sections. Terms for three of them are commonly used: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric, or suprapubic Common or Concerning Symptoms • Indigestion or anorexia • Nausea, vomiting, or hematemesis • Abdominal pain • Dysphagia and/or odynophagia • Change in bowel function • Constipation or diarrhea • Jaundice “How is your appetite?” • Anorexia, nausea, vomiting in many gastrointestinal disorders; and – also in pregnancy, – diabetic ketoacidosis, – adrenal insufficiency, – hypercalcemia, – uremia, – liver disease, – emotional states, – adverse drug reactions – Induced but without nausea in anorexia/ bulimia. • Anorexia is a loss or lack of appetite. • Some patients may not actually vomit but raise esophageal or gastric contents in the absence of nausea or retching, called regurgitation. – in esophageal narrowing from stricture or cancer; also with incompetent gastroesophageal sphincter • Ask about any vomitus or regurgitated material and inspect it yourself if possible!!!! – What color is it? – What does the vomitus smell like? – How much has there been? – Ask specifically if it contains any blood and try to determine how much? • Fecal odor – in small bowel obstruction – or gastrocolic fistula • Gastric juice is clear or mucoid. Small amounts of yellowish or greenish bile are common and have no special significance. • Brownish or blackish vomitus with a “coffee- grounds” appearance suggests blood altered by gastric acid. -

Observational Study of Children with Aerophagia

Clinical Pediatrics http://cpj.sagepub.com Observational Study of Children With Aerophagia Vera Loening-Baucke and Alexander Swidsinski Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008; 47; 664 originally published online Apr 29, 2008; DOI: 10.1177/0009922808315825 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/47/7/664 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Clinical Pediatrics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cpj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 18 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/47/7/664 Downloaded from http://cpj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on August 26, 2008 © 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Clinical Pediatrics Volume 47 Number 7 September 2008 664-669 © 2008 Sage Publications Observational Study of Children 10.1177/0009922808315825 http://clp.sagepub.com hosted at With Aerophagia http://online.sagepub.com Vera Loening-Baucke, MD, and Alexander Swidsinski, MD, PhD Aerophagia is a rare disorder in children. The diagnosis is stool and gas. The abdominal X-ray showed gaseous dis- often delayed, especially when it occurs concomitantly tention of the colon in all and of the stomach and small with constipation. The aim of this report is to increase bowel in 8 children. Treatment consisted of educating awareness about aerophagia. This study describes 2 girls parents and children about air sucking and swallowing, and 7 boys, 2 to 10.4 years of age, with functional consti- encouraging the children to stop the excessive air swal- pation and gaseous abdominal distention. -

Management of Travellers' Diarrhoea in Adults In

MANAGEMENT OF TRAVELLERS’ DIARRHOEA IN ADULTS IN PRIMARY CARE Homerton University Hospital and Hospital for Tropical Diseases December 2016 (review date December 2017) Presence of Assess as per NICE • Diarrhoea +/- nausea / vomiting and >3 loose stools per day guidelines on acute • PLUS travel outside of Western Europe / N America / Australia / diarrhoea New Zealand NO https://cks.nice.org • OR diarrhoea in men who have sex with other men (MSM) even in .uk/diarrhoea- the absence of foreign travel adults-assessment YES Refer to Homerton Infectious Diseases (ID) clinic (box Duration > 2 weeks 3) & commence stool investigations (MC&S, OCP +/- YES C difficle toxin test) NO Features of severe illness: • Fever >38.5 +/- bloody diarrhoea +/- severe abdominal pain OR • Immunocompromised (chemotherapy/ after tissue transplant/HIV with a low CD4 count) • Underlying intestinal pathology (inflammatory bowel disease/ ileostomy/short bowel syndrome) • Conditions where reduced oral intake may be dangerous (diabetes, sickle cell disease, elderly) YES Refer to YES • Dehydrated? Homerton • Evidence of sepsis? A&E (box 3) • Fever plus travel to malaria-endemic area NO • Acute abdomen/ signs suggestive of appendicitis? • Unable to manage at home/ clinician concern NO Diarrhoea with risk factors for severe illness/ Non-severe illness complications Investigations Investigations • Stool MC&S • Stool MC&S • Stool OC&P x 2 • Stool OC&P x 2 • C. difficile toxin test - if recent • C. difficile toxin test - if recent hospitalisation hospitalisation or antibiotics -

A Pocket Manual of Percussion And

r — TC‘ B - •' ■ C T A POCKET MANUAL OF PERCUSSION | AUSCULTATION FOB PHYSICIANS AND STUDENTS. TRANSLATED FROM THE SECOND GERMAN EDITION J. O. HIRSCHFELDER. San Fbancisco: A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, PUBLISHEBS, BOOKSELLEBS & STATIONEB3. 1873. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, By A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, Iii the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. TRAN jLATOR’S PREFACE. However numerou- the works that have been previously published in the Fi 'lish language on the subject of Per- cussion and Auscultation, there has ever existed a lack of a complete yet concise manual, suitable for the pocket. The translation of this work, which is extensively used in the Universities of Germany, is intended to supply this want, and it is hoped will prove a valuable companion to the careful student and practitioner. J. 0. H. San Francisco, November, 1872. PERCUSSION. For the practice of percussion we employ a pleximeter, or a finger, upon which we strike with a hammer, or a finger, producing a sound, the character of which varies according to the condition of the organs lying underneath the spot percussed. In order to determine the extent of the sound produced, we may imagine the following lines to be drawr n upon the chest: (1) the mammary line, which begins at the union of the inner and middle third of the clavicle, and extends downwards through the nipple; (2) the paraster- nal line, which extends midway between the sternum and nipple ; (3) the axillary line, which extends from the centre of the axilla to the end of the 11th rib. -

The Older Adult 20

CHAPTER The Older Adult 20 Older adults now number more than 25 million people in the United States and are expected to reach 80 million by 2050.1 These seniors will live longer than previous generations: life span at birth is currently 79 years for women and 74 years for men. Those older than 85 years are projected to increase to 5% of the U.S. population within 40 years. Hence, the “demographic im- perative” is to maximize not only the life span but also the “health span” of our older population, so that seniors maintain full function for as long as possible, enjoying rich and active lives in their homes and communities. Clinicians now recognize frailty as one of society’s common myths about aging—more than 95% of Americans older than 65 years live in the commu- nity, and only 5% reside in long-term care facilities.1,2 Over the past 20 years, seniors actually have become more active and less disabled. These changes call for new goals for clinical care—“an informed activated patient inter- acting with a prepared proactive team, resulting in high quality satisfying en- counters and improved outcomes”3—and a distinct set of clinical attitudes and skills. CHAPTER 20 I THE OLDER ADULT 839 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY Assessing the older adult presents special opportunities and special challenges. Many of these are quite different from the disease-oriented approach of his- tory taking and physical examination for younger patients: the focus on healthy or “successful” aging; the need to understand and mobilize family, social, and community supports; the importance of skills directed to func- tional assessment, “the sixth vital sign”; and the opportunities for promoting the older adult’s long-term health and safety. -

Bates' Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

Lynn S. Bickley, MD, FACP Clinical Professor of Internal Medicine School of Medicine University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Peter G. Szilagyi, MD, MPH Professor of Pediatrics Chief, Division of General Pediatrics University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York Acquisitions Editor: Elizabeth Nieginski/Susan Rhyner Product Manager: Annette Ferran Editorial Assistant: Ashley Fischer Design Coordinator: Joan Wendt Art Director, Illustration: Brett MacNaughton Manufacturing Coordinator: Karin Duffield Indexer: Angie Allen Prepress Vendor: Aptara, Inc. 7th Edition Copyright © 2013 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2009 by Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2007, 2004, 2000 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 1995, 1991 by J. B. Lippincott Company. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appear- ing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at Two Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia PA 19103, via email at [email protected] or via website at lww.com (products and services). 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bickley, Lynn S. Bates’ pocket guide to physical examination and history taking / Lynn S.