Napa-Park-Police-2001.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC Park Crime Stats

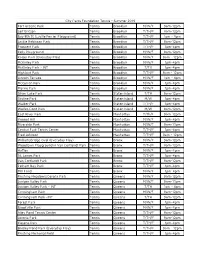

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014 Social Assessment White Paper No. 2 March 2016 Prepared by: D. S. Novem Auyeung Lindsay K. Campbell Michelle L. Johnson Nancy F. Sonti Erika S. Svendsen Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Analysis........................................................................................................................................ 15 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Park Profiles ........................................................................................................................................ -

What Is the Natural Areas Initiative?

NaturalNatural AAreasreas InitiativeInitiative What are Natural Areas? With over 8 million people and 1.8 million cars in monarch butterflies. They reside in New York City’s residence, New York City is the ultimate urban environ- 12,000 acres of natural areas that include estuaries, ment. But the city is alive with life of all kinds, including forests, ponds, and other habitats. hundreds of species of flora and fauna, and not just in Despite human-made alterations, natural areas are spaces window boxes and pet stores. The city’s five boroughs pro- that retain some degree of wild nature, native ecosystems vide habitat to over 350 species of birds and 170 species and ecosystem processes.1 While providing habitat for native of fish, not to mention countless other plants and animals, plants and animals, natural areas afford a glimpse into the including seabeach amaranth, persimmons, horseshoe city’s past, some providing us with a window to what the crabs, red-tailed hawks, painted turtles, and land looked like before the built environment existed. What is the Natural Areas Initiative? The Natural Areas Initiative (NAI) works towards the (NY4P), the NAI promotes cooperation among non- protection and effective management of New York City’s profit groups, communities, and government agencies natural areas. A joint program of New York City to protect natural areas and raise public awareness about Audubon (NYC Audubon) and New Yorkers for Parks the values of these open spaces. Why are Natural Areas important? In the five boroughs, natural areas serve as important Additionally, according to the City Department of ecosystems, supporting a rich variety of plants and Health, NYC children are almost three times as likely to wildlife. -

Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010

PL-P1 CT: Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010 Total Population 319 8,000 or more 343 6,500 to 7,999 5,000 to 6,499 337 323 345 414 442 3,500 to 4,999 451.02 444 2,500 to 3,499 449.02 434 309 449.01 451.01 418 436 Less than 2,500 351 435 448 Van Cortlandt Park 428 420 430 H HUDSONPKWY 307.01 BROADWAY 422 426 335 408 424 456 406 285 394 484 295 I 87 MOSHOLU PKWY 404 458 283 297 396 281 301 431 392 287 279 398 460 BRONX RIVER PKWY 293.01 421 390 293.02 289 378 388 386 277 462.02 504 Pelham Bay Park 380 409 423 429.02 382 419 411 368 376 374 462.01 273 413 429.01 372 364 358 370 267.02 407.01 425 415 267.01 403.03 407.02 348 403.02 336 338 340 342 344 350 403.04 405.01 360 356 DEEGAN EXWY 261 265 405.02 269 263 401 399.01 332.02 W FORDHAM RD 397 316 312 302 E FORDHAM RD 330 328 324 326 318 314 237.02 310 257 253 399.02 255 237.03 334 332.01 239 HUTCHINSON RIVER PKWY 387 Botanical Gardens 249 383.01383.02 Bronx Park BX AND PELHAM PKWY 247 251 224.03 237.04 385 389 245.02 224.01 248 296 288 Hart Island 228 276 Cemetery 245.01 243 241235.01 391 224.04 53 393 250 300 235.02381 379 375.04 205.02 246 215.01 233.01 286 284 373 230 205.01 233.02 395 254 215.02 266.01 227.01 371 232 252 516 229.01 231 244 266.02 213.01 217 236 CROSS BRONX EXWY 365.01 227.02 369.01 363 256 229.02 238 213.02 209 227.03 165 200 BRUCKNER EXWY 201 369.02 365.02 361 274.01 240 264 367 220 210.01 204 211 223 225 171 167 359 219 163 274.02 221.01 169 Crotona Park 210.02 202 193 221.02 60 218 216.01 184 161 216.02 199 179.02 147.02 212 206.01 177.02 155 222 197 179.01 96 147.01 194 177.01 153 62 76 I 295 157 56 64 181.02 149 92 164 189 145 151 181.01175 72 160 195 123 54 70 166 183.01 68 78 162 125 40.01 183.02 121.01 135 50.02 48 GR CONCOURSE 173 143 185 44 BRUCKNER EXWY 152 131 127.01 121.02 52 CROSS BRONX EXWY DEEGAN EXWY 63 98 SHERIDAN EXWY 50.01 158 59.02 141 42 133 119 61 129.01 159 46 69 138 28 144 38 77 115.02 74 86 67 87 130 75 89 16 Sound View Park 110 I 295 65 71 20 24 90 79 85 84 132 118 73 BRUCKNER EXWY 43 83 51 2 37 41 35 31 117 4 39 23 93 33 25 27.02 27.01 19 1 Source: U.S. -

Applicant Information Metal Detector Permit

METAL DETECTOR PERMIT City of New York Parks & Recreation Adrian Benepe, Commissioner Michael Dockett, Assistant Commissioner of 2011 APPLICATION Urban Park Services APPLICANT INFORMATION Applicant: ______________________________________________________________ ( ) ________-_____________ NAME TELEPHONE NUMBER ____________________________________ ______ _____________________ ADDRESS ZIP CODE E-MAIL ADDRESS The applicant (“Applicant”), should he/she be granted a permit, agrees to fully obey all the conditions set forth on this application as well as the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation’s (hereinafter “Parks” or “Agency”) Rules and Regulations and any other applicable City, state or federal laws, rules or regulations. In addition, Applicant must: (1) provide to Parks an acceptable form of photo identification which documents Applicant’s current address (e.g. State Driver’s License or other government issued identification); (2) surrender all expired Metal Detecting Permit(s) previously issued to applicant by Parks, (if applicable); and (3) a list of all Significant Objects (as defined below) found during the prior year under a duly issued Parks permit, if applicable. PERMITTED AREAS FOR METAL DETECTING ACTIVITY Metal Detecting activities are restricted to the open areas (other than the areas listed in Paragraph 8 of the Permit Conditions) in the following parks: Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Queens cont’d Bronx Park Canarsie Park East River Park **Alley Pond Park Highland Park Claremont Park Marine Park Highbridge Park -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

A Seasonal Guide to New York City's Invertebrates

CENTER FOR BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION A Seasonal Guide to New York City’s Invertebrates Elizabeth A. Johnson with illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne CENTER FOR BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION A Seasonal Guide to New York City’s Invertebrates Elizabeth A. Johnson with illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne Ellen V. Futter, President Lewis W. Bernard, Chairman, Board of Trustees Michael J. Novacek, Senior Vice-President and Provost of Science TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................2-3 Rules for Exploring When to Look Where to Look Spring.........................................................................................4-11 Summer ...................................................................................12-19 Fall ............................................................................................20-27 Winter ......................................................................................28-35 What You Can Do to Protect Invertebrates.............................36 Learn More About Invertebrates..............................................37 Map of Places Mentioned in the Text ......................................38 Thanks to all those naturalists who contributed information and to our many helpful reviewers: John Ascher, Allen Barlow, James Carpenter, Kefyn Catley, Rick Cech, Mickey Maxwell Cohen, Robert Daniels, Mike Feller, Steven Glenn, David Grimaldi, Jay Holmes, Michael May, E.J. McAdams, Timothy McCabe, Bonnie McGuire, Ellen Pehek, Don -

Cunningham Park

THERE’S SOMETHING TO DO FOR EVERYONE AT CUNNINGHAM PARK- Tennis Courts- 20 HOW TO FIND US- NYC DEPARTMENT OF Baseball/Softball Fields- 24 BY CAR- PARKS & RECREATION Football Fields- 1 Soccer Fields- 3 From Grand Central Parkway- Cricket Pitches- 1 Exit at Francis Lewis Boulevard (Northbound Bocce Courts- 2 Exit). Take Francis Lewis to Union Turnpike and 2009 SEASON Basketball Courts- 2 make a left. Make your second left into the parking Playgrounds- 4 lot at 196th Place. Spray Showers- 3 From Long Island Expressway- Comfort Stations- 4 Jogging/Walking Track Exit at Francis Lewis Boulevard. Go south on WELCOME TO Biking Path (Motor Parkway-199 St./75 Ave.) Francis Lewis (make right from eastbound exit or left from westbound exit). Go to Union Turnpike Mountain Bike Trails (210 St. & 67 Ave.) CUNNINGHAM and make a right. Make your second left into the Barbecue/Picnic Areas parking lot at 196th Place. Community Center PARK Summer Day Camp **IF PARKING LOT ON 196TH PLACE & UNION TURNPIKE IS FULL-** Here is a list of some of the yearly events at Cunningham Park- Make a right turn at lot exit back onto Union Turn- pike. Make right turn onto Francis Lewis Boulevard, Big Apple Circus (May 16 to May 31) then make the next right turn back into the back of www.bigapplecircus.org the park. Follow the park road to the top of the hill and look for parking lot on your right side. USMC Aviation Demo- Moved to Flushing Meadow Park for 2009 Metropolitan Opera BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION- NO SHOW IN 2009 New York Philharmonic Q46 BUS- NO SHOW IN 2009 Friends of Cunningham Park Music Concert Bus runs east to west along Union Turnpike. -

Rent Levels Across

MANHATTAN BRONX LABEL NAME The LABEL NAME 1 Bater y Park 13 Central Park West 1 North New York 2 Greenwich Village 14 Fifh Av enue Bronx 2 St Marys Park 3 Lower East Side 15 Yorkville 3 Highbridge 4 Hells Kitchen 16 Columbia University 4 Morrisania 5 Chelsea 17 Manhatanvi lle 5 Fordham Heights 6 Madison Square 18 Mount Morris Park Rent Levels Across NYC 6 Bronx Park 7 Stuyvesant Square 19 Jeffer son Park 7 Jerome Park Reservoir 8 De Wit Cl int on 20 Harlem Bridge based on the 1940 Census 8 Riverdale 9 Columbus Circle 21 City College 9 Hunts Point 10 Times Square 22 Harlem 10 Clason Point 1940 rents 11 Plaza 23 Washington Heights 11 Throgs Neck 12 Queensboro Bridge 24 Inwood adjusted for inflation: n a 12 Park Versailles t t 13 Union Port a h 14 Pelham Bay Park $150 in 1940 n 15 Westchester Heights a = $2,458 in 2012 M 16 Williamsbridge 17 Gun Hill Road 18 Baychester 19 Woodlawn 20 Edenwald $30 in 1940 = $492 in 2012 Queens BROOKLYN LABEL NAME QUEENS 1 Greenpoint 8 South Brooklyn 15 Kensington 22 Flatlands LABEL NAME 2 WIlliamsburg 9 Park Slope 16 Flatbush 23 Mill Basin 1 Astoria 3 English Kills 10 Eastern Parkway 17 Holy Cross 24 Canarsie 2 Long Island CIty 4 Brooklyn Heights 11 Brownsville 18 Bay Ridge 25 Spring Creek Basin 3 Sunnyside 4 Woodside Winfiel d 5 Fort Greene Park 12 Highland Park 19 Bensonhurst 26 Sea Gate 5 Jackson Heights 6 Stuyvesant 13 Sunset Park 20 Gravesend 27 Neck Road 6 Corona 7 Bushwick 14 Borough Park 21 South Greenfiel d 28 Coney Island 7 Maspeth Brooklyn 8 Elmhurst S Elmhurst 9 Ridgewood Glendale 10 Nassau Heights STATEN ISLAND 11 Forest Hills 12 Flushing South LABEL NAME 13 Flushing 1 Brighton 14 College Point 15 Whitestone 2 Stapleton 16 Bayside 3 Dongan Hills 17 Douglaston Litle Ne ck 4 Port Richmond 18 Woodhaven 19 Ozone Park 5 Mariner's Harbor 20 Richmond Hill 6 Travis 21 Jamaica 7 Great Kills Staten 22 South Jamaica Island 23 Hollis 8 Prince's Bay 24 Queens Village 9 Totenvi lle 25 Howard Beach 26 Springfiel d 27 St Albans 28 Laurelton Rosedale 29 South Laurelton 30 Neponsit 31 Hammels Visit www.1940snewyork.com for more information. -

Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan

Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan NYC Department of City Planning • 2006 Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Queens East River and North Shore Greenway Master Plan New York City Department of City Planning New York City Department of Parks & Recreation 2006 2006 • NYC Department of Parks & Recreation Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Project PIN X500.97 The preparation of this report was fi nanced in part through funds from the U.S.Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report refl ect the views of the author, who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented within. The contents do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specifi cation, or regulation. NYC Department of City Planning • 2006 Queens East River & North Shore Greenway Master Plan Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Project Description ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area -

Untitled Spreadsheet

City Parks Foundation Tennis - Summer 2019 Fort Greene Park Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 9am-12pm Leif Ericson Tennis Brooklyn T/TH/F 9am-12pm Bay 8th St (Lucille Ferrier Playground) Tennis Brooklyn T/TH/F 1pm - 4pm Jackie Robinson Park Tennis Brooklyn T/TH/F 9am-12pm Prospect Park Tennis Brooklyn T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Kelly Playground Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 9am-12pm Kaiser Park (Everyday Play) Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 9am - 12pm McKinley Park Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 1pm-4pm McKinley Park - INT Tennis Brooklyn T/TH 1pm-4pm Highland Park Tennis Brooklyn T/TH/F 9am - 12pm Lincoln Terrace Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 1pm - 4pm McCarren Park Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 1pm-4pm Marine Park Tennis Brooklyn M/W/F 1pm-4pm Silver Lake Park Tennis Staten Island T/TH 9am-12pm Skyline Park Tennis Staten Island M/W 1pm-4pm Walker Park Tennis Staten Island T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Wolfes Pond Park Tennis Staten Island M/W 9am-12pm East River Park Tennis Manhattan T/Th/F 9am-12pm Inwood Hill Tennis Manhattan M/W/F 1pm-4pm Riverside Park Tennis Manhattan M/W/F 9am-12pm Central Park Tennis Center Tennis Manhattan T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Fred Johnson Tennis Manhattan T/TH/F 9am - 12pm Williamsbridge Oval (Everyday Play) Tennis Bronx M/W/F 9am-12pm Woodlawn Playground in Van Cortlandt Park Tennis Bronx T/TH/F 9am-12pm Haffen Tennis Bronx M/W/F 1pm-4pm St. James Park Tennis Bronx T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Van Cortlandt Park Tennis Bronx T/TH/F 9am-12pm Pelham Bay Park Tennis Bronx T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Mill Pond Tennis Bronx M/W/F 1pm-4pm Flushing Meadows/Corona Park Tennis Queens M/W/F 9am-12pm Juniper Valley Park Tennis Queens M/W/F 9am-12pm Juniper Valley Park - INT Tennis Queens T/TH 1pm - 4pm Cunningham Park Tennis Queens M/W/F 9am-12pm Cunningham Park -INT Tennis Queens T/TH 9am-12pm Forest Park Tennis Queens M/W/F 1pm-4pm Brookville Park Tennis Queens M/W/F 1pm-4pm Alley Pond Tennis Center Tennis Queens T/TH/F 9am-12pm Astoria Park Tennis Queens T/TH/F 9am-12pm Kissena Park Tennis Queens T/TH/F 1pm-4pm Baisley Pond Park (Everyday Play) Tennis Queens T/TH/F 9am - 12pm Flushing Memorial Field Tennis Queens T/TH/F 1pm-4pm. -

3Rd QTR PARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS (All Figures Are Subject to Further Analysis and Revision) Report Covering the Period Between July1, 2015 and Sept

3rd QTR PARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS (All figures are subject to further analysis and revision) Report covering the period Between July1, 2015 and Sept. 30, 2015 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY MURDER RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.747 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 0 0 0 0 1 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.430 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 002 1 0 3 0 6 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.564 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 1 0 5 0 7 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.320 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.690 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 025 6 1 9 0 23 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.970 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.000 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 003 0 0 0 0 3 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.430 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 1 0 1 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.373 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 101 2 0 2 0 6 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.350 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 0 0 0 0 1 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.514 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 2 0 2 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.250 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 005 3 0 7 0 15 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.860 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 003 2 1 0 0 6 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.160 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 0 0 0 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.800 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 001 1 0 0 0 2 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.203 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 004 2 0 8 0 14 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.000 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 000 0 0 1 0 1 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.983 ONE