Stories of Tamil Heritage Language Users As Multilingual Malaysians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINING TOWERING LEADERSHIP.Indd

SUSTAINING TOWERING LEADERSHIP: The Fellow Kanan Legacy INSTITUT AMINUDDIN BAKI KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN MALAYSIA SRI LAYANG GENTING HIGHLANDS Sustaining Towering Leadership: The Fellow Kanan Legacy by Dato’ Mohd Rauhi Bin Mohd Isa Loji Bin Haji Saibi, Ph.D Haji Ariffi n @ Mat Yaakob Bin Abdul Rahman Haji Md Yusoff Bin Othman Hajah Junaidi Binti Santano Wan Hamzah Bin Wan Daud Haji Mohd Kholil Bin Mohamad Institut Aminuddin Baki Highlands Branch (Institute of Educational Management and Leadership) Ministry of Education, Malaysia Editors Jamilah Binti Jaafar, Ph.D Hajah Nor Hasimah Binti Hashim Parimala a/p Thanabalasingam Published in Malaysia by INSTITUT AMINUDDIN BAKI Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia Kompleks Pendidikan Nilai, 71760 Bandar Enstek, Negeri Sembilan Darul Khusus Tel: 06-7979 200 Faks: 06-7079 300 www.iab.edu.my Publishing Management INSTITUT AMINUDDIN BAKI GENTING HIGHLANDS BRANCH (National Institute of Educational Management and Leadership) Ministry of Education, Malaysia Sri Layang, 69000 Genting Highlands http://www.iab.edu.my [email protected] Copyright Reserved (C) 2015 Institut Aminuddin Baki Cawangan Genting Highlands No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Director of Institut Aminuddin Baki, Ministry of Education, Malaysia. ISBN 978-967-0504-24-7 9 789670 504247 Publication Manager Hajah Nor Hasimah Binti Hashim Graphic Designer Rosdi bin Idris Printed by H.S. Massyi Printing Sdn. Bhd. 40, Jalan Selaseh Indah Taman Selaseh Fasa 1 68100 Batu Caves Selangor Darul Ehsan Sustaining Towering Leadership: The Fellow Kanan Legacy Patron YH. -

Konvokesyen Uitm Ke - 89 89Th Convocation Ceremony

Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 89 89th Convocation Ceremony CANSELOR CHANCELLOR Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda His Majesty The Yang Di-Pertuan Agong XV Sultan Muhammad V D.K., D.K.M., D.M.N., D.K. (Selangor), D.K. (Negeri Sembilan), D.K. (Johor), D.K. (Perak), D.K. (Perlis), D.K. (Kedah), D.K. (Terengganu), S.P.M.K., S.J.M.K., S.P.K.K., S.P.S.K., S.P.J.K. MENTERI PENDIDIKAN MINISTER OF EDUCATION YB Dr. Maszlee bin Malik PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YABhg. Tun Datuk Seri Panglima Hj. Ahmadshah Abdullah S.M.N., D.M.K., S.P.D.K., D.P., P.G.D.K., A.S.D.K., K.M.N., J.P. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Utama (Dr) Arshad Ayub P.S.M., S.P.M.S., S.U.N.S., S.P.M.P., S.P.S.K., P.N.B.S., D.P.M.P., D.P.M.J., D.S.A.P., D.P.M.T., D.S.L.J., (Brunei), P.G.D.K , J.M.N, P.B.E. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Dr Abdul Rahman Arshad P.S.M., S.P.M.S., S.P.D.K., D.C.S.M., D.S.A.P., D.M.P.N., D.K.S.J., J.M.N., J.S.M., B.S.K., Ph.D. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Sri (Dr) Sallehuddin Mohamed P.M.N., P.S.M., S.S.A.P., S.S.I.S., S.I.M.P., D.H.M.S., D.I.M.P., J.M.N., K.M.N. -

9789814841580

DISCOVER F For Review D onlyISCOVER ATIVE BOOK THAT A FUN AND INFORM ATORS ORE BUDDING YOUNG INVESTIG INTRODUCES N sic ICS FORENSIC SCIENCE! S OF N E V WORLD OR ESTIGATIONS TO THE F FOR IN 2 S S MORE WAYS TO USE SCIENCE 2 Every crime scene has clues if you know where to look. M RE Examining these clues using forensic methods can help you O solve even the most mysterious crimes. In this book, you WAY will learn from forensic experts how to analyse all sorts of S evidence, from fingerprints and knots to unknown materials T O and substances. U S E S C Filled with colourful illustrations, hands-on activities and true IE DISCOVER FORENsics 2 N crime cases, is your best guide to thinking ce like a forensic scientist. By applying the correct techniques for and inquiry-based principles – and avoiding the myths that are IN commonly depicted on TV – you might just uncover the truth V ES of what happened! T I G AT I The Forensic Experts Group (TFEG) is a team of accomplished forensic O N scientists with more than 80 years of combined experience and specialised S knowledge. The first private and independent forensic laboratory in Singapore, TFEG serves as a one-stop centre for a wide spectrum of forensic services. TFEG’s forensic scientists have worked on hundreds of cases, including many high-profile ones. Through its Discover Forensics SeriesTM of workshops, talks and learning journeys, TFEG is bringing forensic science literacy to a new generation of young minds. -

So Tahun Uitm LAPORAN TAHUNAN O F| F) C Universiti Teknologi MARA Dl U U U Msst* Mr

so Tahun uiTM LAPORAN TAHUNAN O f| f) C Universiti Teknologi MARA dL U U U mSSt* Mr - «' ;: ,<;v UNIVERSITI ^ TEKNOLOGl MARA 50 Tahun UiTM 1956 - 2006 Kecemerlangan Berterusan 11 L&A •/> "!*•# "% S ^^MBPK1 ^ m \ VermuCanya Sebuah Sejaral : Vewan Latefian %ida 19 DEWAI * 11H i RI04 Iflfl CANSELOR SERI PADUKA BAGINDA YANG DI-PERTUAN AGONG XII TUANKU SYED SIRAJUDDIN IBNI AL-MARHUM TUANKU SYED PUTRAJAMALULLAIL •^~%- SERI PADUKA BAGINDA RAJA PERMAISURI AGONG TUANKU FAUZIAH BINTI AL-MARHUM TENGKU ABDUL RASHID ^f- PRO-CANSELOR Y.BHG. TAN SRI DATUK AMAR DR. SULAIMAN HAJI DAUD PRO-CANSELOR Y.BHG. TAN SRI DATUK HAJI ARSHAD AYUB PRO-CANSELOR Y.BHG. TAN SRI DATUK SERI PANGLIMA DR. ABDUL RAHMAN ARSHAD PENGERUSI LEMBAGA PENGARAH Y.BHG. TAN SRI DATO' DR. WAN MOHD ZAHID MOHD NOORDIN >Ji] NAIB CANSELOR Y.BHG. DATO' SERI PROF. DR. IBRAHIM ABU SHAH -4^ m m UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MARA LEMBAGA PENGARAH Yang Berhormat Dato' Mustafa Mohamed Menteri Pengajian Tinggi Kementerian Pengajian Tinggi Malaysia Aras 7, Blok E3 Presint 1, Parcel E Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62505 PUTRAJAYA Assalamu'alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh Yang Berhormat Dato' Lembaga Pengarah Universiti Teknologi MARA dengan hormatnya menyampaikan Laporan Tahunan UiTM bagi tahun 2006 mengikut kehendak Bahagian IV Seksyen 30 (1) Akta Universiti Teknologi MARA 1976. Wassalam. Dengan penuh hormat. TAN SRI DATO' DR. WAN MOHD ZAHID MOHD NOORDIN Pengerusi Lembaga Pengarah Universiti Teknologi MARA Tarikh: 17 Laporan Tahunan 20061 Universiti Teknologi MARA I wr' * T# 1 n jHmp^K V ""TI '"TT - ,„ „» tl • I 111 I —*• Wt ••/ i » # \ •. M MemorL. institut ftknoCogt MAJLAII 967 Maklumat Korporat 20 Pihak Berkuasa Universiti 28 Jawatankuasa Pengurusan Universiti 32 1 Laporan Naib Canselor 44 •* 0 Laporan Aktiviti Dan Persatuan 52 Laporan Penyata Kewangan 66 MAKLUMAT KORPORAT IJ: •• • UNtviism Mempertingkatkan keilmuan dan kepakaran bumiputera dalam semua bidang menerusi penyampaian program profesional, penyelidikan serta penglibatan khidmat masyarakat yang berlandaskan kepada nilai- nilai murni dan etika keprofesionalan. -

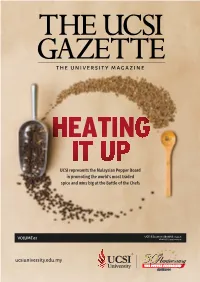

University UCSI

UCSI represents the Malaysian Pepper Board in promoting the world's most traded spice and wins big at the Battle of the Chefs UCSI Education Sdn Bhd (185479-U) VOLUME 07 KDN:PQ/PP/1505/(18824)-(8) ® ucsiuniversity.edu.my UCSI University CONTENTS UCSI WELCOMES THREE DISTINGUISHED UNIVERSITY COUNCIL MEMBERS HEATING IT UP UCSI represents the Malaysian Pepper Board and wins big at the Battle of the Chefs UCSI CELEBRATES 29TH CONVOCATION CEREMONY PERSON OF THE MONTH Dr Joanne Yeoh HANDS OF HOPE Gifting refugee children with free education WRITE RIGHT Jason Kwong Insights from some of Malaysia’s most experienced authors and journalists Publisher: UCSI Education Sdn Bhd (185479-U) Nets Printwork Sdn Bhd (KDN:PQ1780/3379) No. 1, Jalan Menara Gading, UCSI Heights, Taman Connaught, No. 58, Jalan PBS 14/4, Taman Perindustrian Bukit Serdang Cheras 56000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 43300 Seri Kembangan, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. T +603 9101 8880 F +603 9102 2614 T +603-8213 6288 F +603-8959 5577 ucsiuniversity.edu.my 03 MESSAGE FROM THE VICE-CHANCELLOR AND PRESIDENT WELCOME TO OUR NEW STUDENTS. As the curtain rises for the next important stage of your life — university — you must be going through a period of mixed joy, excitement and anxieties. I believe that this chapter is going to be a little different. The preceding ones were largely written for you by others — your parents or guardians, families and teachers. Now, you are the leading author and you will be helming the direction, plot and height of your story. Daunting as it may be, do rest assured that all of the members of the UCSI University family will be there for you as you navigate the opportunities and challenges in the course of your studies here. -

E-Buku Konvo Uitm Ke-90 | Cawangan Pulau Pinang

ke - 90th Convocation Ceremony 2 Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 CANSELOR Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri’ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta’in Billah D.K.P., D.K., D.M.N., S.S.A.P., S.I.M.P., D.K.(Terengganu)., D.K.(Johor)., S.P.M.J., P.A.T. Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 3 4 Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Raja Permaisuri Agong Tunku Hajah Azizah Aminah Maimunah Iskandariah Binti Almarhum Al-Mutawakkil Alallah Sultan Iskandar Al-Haj D.K., S.S.A.P., S.I.M.P., D.K.(Johor)., S.P.M.J. Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 5 MENTERI PENDIDIKAN MINISTER OF EDUCATION YB Dr. Maszlee Malik Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 7 PRO CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YABhg. Tun Datuk Seri Panglima Hj. Ahmadshah Abdullah S.M.N., D.M.K., S.P.D.K., D.P., P.G.D.K., A.S.D.K., K.M.N., J.P. Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 9 PRO CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Utama (Dr) Arshad Ayub P.S.M., S.P.M.S., S.U.N.S., S.P.M.P., S.P.S.K., P.N.B.S., D.P.M.P., D.P.M.J., D.S.A.P., D.P.M.T., D.S.L.J (Brunei), P.G.D.K., J.M.N., P.B.E. Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 90 11 PRO CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. -

The Study of Self-Esteem, Academic Self-Image and Oral Skills with Reference to English As a Second Language in Malaysia

The study of Self-Esteem, Academic Self-Image and Oral skills with reference to English as a Second Language in Malaysia. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Azizah Bte Rajab School of Education University of Leicester July 1996 UMI Number: U084521 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U084521 Published by ProQuest LLC 2015. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CTo tfie memory o f my Cate motfier Acknowledgements I owe my sincere thanks to my supervisor Dr. Martin Cortazzi for his guidance during the course of this study; Ms. Sylvia McNamara who taught me much about self-esteem and group-work with the children; Dr. Linda Hargreaves who has been very kind to comment critically on this thesis at the early stage and Dr. Clive Sutton who provided valuable help and assistance in co-ordinating the academic matters. Julie Thompson, secretary in the Research Office assisted me enthusiastically during the tenure of this study. All the above are in the School of Education, University of Leicester, UK. -

Download Download

RJHIS 4 (2) 2017 The 2014 Teluk Intan parliamentary by-election in Malaysia Ariff Aizuddin Azlan* Zulkanain Abdul Rahman* Mohammad Tawfik Yaakub* Abstract: Democracy, by definition, is fit to be perceived as the equality of political right. The 2014 Teluk Intan parliamentary by-election contributed towards improving the indicator of democracy. This by-election also witnessed a direct contest between GERAKAN, one of BN component parties, and DAP, a member of the opposition PR coalitions. This paper analyses that this by-election had posed serious formidable challenges for both competing parties. It also looks at the campaign strategies and issues during the ongoing campaign sessions. The result, however, did not reflect the expectations held by the DAP, as it thought that it could maintain the present status quo. The study concluded that, instead of achieving electoral victory, DAP was caught in its internal unexpected crisis, irrespective of the PR coalition members, and, thus, failed to retain its former seat within the context of parliamentary democracy. Keywords: Pakatan Rakyat, by-election, Teluk Intan, Barisan Nasional, Malaysia * Ariff Aizuddin Azlan is a PhD candidate in Malaysian Politics at the Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya (UM). E-mail: [email protected]. * Dr. Zulkanain Abdul Rahman is an Associate Professor in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya (UM). E-mail: [email protected]. * Mohammad Tawfik Yaakub is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Institute of Graduate Studies (IGS), University of Malaya (UM). E-mail: [email protected]. -

Understanding International School Choice in Malaysia

SPHERES OF INFLUENCE: UNDERSTANDING INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL CHOICE IN MALAYSIA by MARCEA LEIGH INGERSOLL A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Education In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Education Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (June, 2010) Copyright ©Marcea Leigh Ingersoll, 2010 i ABSTRACT This study offers a hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry into the experiences of Malaysian parents who selected an international education for their children. Data collection was conducted at one international school in Kuala Lumpur, and consisted of both a survey and interviews. The study focused on parents‘ own educational background and experiences, their expectations and motivations for selecting an international school, factors affecting school choice, and attitudes to cultural and self-identities within the context of international education. Findings suggest that Malaysian parents from different age groups as well as varying ethnic and linguistic backgrounds had similar motivations for sending their children to an international school. From the data analysis, three themes emerged: aspirational priorities, discouraging influences, and enabling factors. By scaffolding my examination within the theory of reproduction in education and notions of social and cultural capital, I examined how multiple forms of economic, cultural, and social capital are recognized and mobilized in the search for a quality education in an increasingly globalized market. I conclude that Malaysian parents in this study chose an international school for their children based on experiences forged in four spheres of influence: individual, social, national, and global. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No single thing is ever accomplished without the efforts of many. This thesis embodies the contributions of many wonderful people who have given me guidance and from whom I have drawn strength and support. -

Konvokesyen Uitm Ke - 89 89Th Convocation Ceremony

Istiadat Konvokesyen UiTM Ke - 89 89th Convocation Ceremony CANSELOR CHANCELLOR Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda His Majesty The Yang Di-Pertuan Agong XV Sultan Muhammad V D.K., D.K.M., D.M.N., D.K. (Selangor), D.K. (Negeri Sembilan), D.K. (Johor), D.K. (Perak), D.K. (Perlis), D.K. (Kedah), D.K. (Terengganu), S.P.M.K., S.J.M.K., S.P.K.K., S.P.S.K., S.P.J.K. MENTERI PENDIDIKAN MINISTER OF EDUCATION YB Dr. Maszlee bin Malik PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YABhg. Tun Datuk Seri Panglima Hj. Ahmadshah Abdullah S.M.N., D.M.K., S.P.D.K., D.P., P.G.D.K., A.S.D.K., K.M.N., J.P. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Utama (Dr) Arshad Ayub P.S.M., S.P.M.S., S.U.N.S., S.P.M.P., S.P.S.K., P.N.B.S., D.P.M.P., D.P.M.J., D.S.A.P., D.P.M.T., D.S.L.J., (Brunei), P.G.D.K , J.M.N, P.B.E. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Dr Abdul Rahman Arshad P.S.M., S.P.M.S., S.P.D.K., D.C.S.M., D.S.A.P., D.M.P.N., D.K.S.J., J.M.N., J.S.M., B.S.K., Ph.D. PRO-CANSELOR PRO-CHANCELLOR YBhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Sri (Dr) Sallehuddin Mohamed P.M.N., P.S.M., S.S.A.P., S.S.I.S., S.I.M.P., D.H.M.S., D.I.M.P., J.M.N., K.M.N. -

And Others TITLE the School Library: Centre for Life-Long Learning

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 324 tS33 IR 053 313 AUTHOR Siong, Wong Kim, Ed.; And Others TITLE The School Library: Centre for Life-Long Learning. Proceedings of the Annual Confe:ence of the International Association of School Librarianship (18th, Subang Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia, July 22-26, 1989). INSTITUTION International Association of School Librarianship, Kalamazoo, Mich. PUB DATE Jun 90 NOTE 582p.; Appendixes 2 through 5 present legibility problems. PUP TYPP CollectPd works - Conference Proceedings (021) Viewpoints (120) -- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elemencary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Learning Resources Centers; *Library Development; Library Education; Library Instruction; *Library Role; Library Skills; *Library Standards; *Lifelong Learning; *Literacy; Media Specialists; Publishing Industry; School Libraries; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS Teacher Librarian Relationship ABSTRACT This conference report contains 5 addresses and 29 reports on the general theme of the school library as a center for iifelc g learning. Submitted by librarians throughout the world, the reports reflect theoretical as well as practical perspectives, and include t.:e following topics:(1) establishing, developing, and evaluating library resource center programs and services;(2) library edw7ation, professional development, and th'role of teacher-librarians; (3) applications of information and educational technology in school resource centers; (4) developing students' tnformation skills and information literacy;(5) promoting reading skills and literacy; and (6) publishing children's books. Experiences from Australia, Canada, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Scandinavia, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States are reflected in these mate2ials. Appendixes include the conference agenda, a list of participants a-d a list of organizing committee members. (SD) *******'**A*********************S********* ****:*************w***** '** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Romanian Journal of History and International Studies Vol. IV

Romanian Journal of History and International Studies Vol. IV •No. 2 •2017 Faculty of History Department of International Relations and World History ISSN-L 2360-638X ISSN online 2559-544X ISSN print 2360-638X 2017 The Romanian Journal of History and International Studies is biannually published by the Literati Association in collaboration with the Centre for Euro-Atlantic Studies and the Department of International Relations and World History at the Faculty of History, University of Bucharest. Bd. Regina Elisabeta No. 4-12, Sector 5, Post Code 030018, Bucharest Tel: 0213145389, Tel/Fax: 0213100680 E-mail: [email protected] Web: rjhis.ro RJHIS is published with the financial support of PORTAL RESEARCH SRL portalresearch.ro Media partner: International Relations Report (ir-report.ro) Copyright © RJHIS 2017 All rights reserved. The publisher bears no responsibility for the editorial content. The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. ISSN-L 2360-638X ISSN online 2559-544X ISSN print 2360-638X Academic Board Bogdan Antoniu - University of Bucharest Ovidiu Bozgan - University of Bucharest Constantin Bușe - University of Bucharest Ioan Chiper - Nicolae Iorga Institute of History, Romanian Academy Adrian Cioroianu - University of Bucharest Marusia Cîrstea – University of Craiova Marian Cojoc – Ovidius University of Constanta Laurențiu Constantiniu - University of Bucharest Rudolf Dinu - University of Bucharest Manuela