Brief of Appellants/Cross-Appellees ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family & Prolife News Briefs

Family & ProLife News Briefs October 2020 ProLifers Hopeful .... and Determined In the Culture In Public Policy 1. Many programs are expanding. For example, 1. Political party platforms are focusing more than 40 Days for Life is now active in hundreds of U.S. ever on life issues. The Libertarian platform states cities and is going on right now through Nov. 1st. life and abortion issues are strictly private matters. People stand vigil, praying outside of abortion The Democrat platform says “every woman should clinics. Also, the nationwide one-day Life Chain have access to ... safe and legal abortion.” The brings out thousands of people to give silent Republican platform states: “we assert the sanctity witness to our concern for a culture of life. And for of human life and ...the unborn child has a those who have taken part in an abortion, the fundamental right to life which cannot be infringed.” Church offers hope through Rachel’s Vineyard, a Respect life groups such as Priests for Life, & program of forgiveness and healing. the Susan B. Anthony List and others are seeking Another example: the Archdiocese of Miami’s election volunteers to get out the vote. Log onto Respect Life Ministry has been offering a monthly their websites if you might like to help. webinar as part of the U.S. Bishops theme of On Sept. 20th a full page ad in the NYTimes was "Walking with Moms: A Year of Service." Septem- signed by hundreds of Democrat leaders urging the ber’s webinar was How to Be a Pregnancy Center party to soften its stance towards abortion. -

Priests for Life Defies Constitution and Conscience

OPPOSITION NOTES AN INVESTIGATIVE SERIES ON THOSE WHO OPPOSE WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH Faithless Politics: Priests for Life Defies Constitution and Conscience INTRODUCTION riests for Life national director Frank Pavone has spent more than 15 years trying vainly to grow his Catholic antichoice group into the mass clerical movement P envisioned in its rhetoric, only to find himself banished to a Texan wasteland. In a country with some 40,000 Catholic priests, Priests for Life (PFL) has never claimed more than 5,000 members—and quietly stopped counting some time around the turn of the 21st century. Unapologetic electoral campaigning, and unabashed cooperation with the most militant antichoice figures, have not brought PFL membership numbers to match the New York priest’s ambitions. Pavone’s nonprofit says it is “for everyone who wants to stop abortion and euthanasia,” “not an association that seeks to be some sort of separate and elite group of priests who claim to be more pro-life than all the rest”1; it boasts the church hierarchy’s approval, strict orthodoxy and a board of archbishops and cardinals. Even by PFL’s own optimistic estimates, however, Pavone appears never to Pavone has always personalized the PFL message and have attracted a membership of more than one in five US priests. His reaction has been to all image, selling himself—often with large photos of himself but give up on the existing priesthood, which he on PFL billboards—much as a candidate for office might do. regularly castigates as too timid on abortion, and to seek to mold young priests in his image at his new Texas refuge. -

Fr. Frank Pavone of Priests for Life on the Consistent Life Ethic

MISSION: We are committed to the protection of life, which is threatened in today's world by war, abortion, poverty, racism, capital punishment, and euthanasia. We believe that these issues are linked under a “consistent ethic of life.” We challenge those working on all or some of these issues to maintain a cooperative spirit of peace, reconciliation, and respect in protecting the unprotected. About Us Consistent Life is a network uniting those who support the consistent life ethic (CLE) of reverence for all life. Our work involves spreading the vision throughout our nation and world by placing ads, attending and presenting at conferences, and producing free literature showing that consistent opposition to killing is a stance of many well-known anti-abortion and anti-war activists and faith groups. We keep the consistent pro-life community updated on relevant issues, news, and action opportunities via our newsletter (twice a year) and one-page e-letter (weekly). We are trying to achieve a revolution in thinking and feeling; an affirmation of peace and nonviolence; recognition of the value of the life, happiness, and welfare of every person; and all the political and structural changes that will bring this about. FAQ Q: Are you a religious or partisan organization? A: No. The majority of our member organizations and members are Christian, but we welcome good people of any or no faith. We are not affiliated with any political party and do not endorse political candidates. We seek to broaden the pro-life movement in order to strengthen protection for life. Q: Are you “really” pro-life? A: Yes. -

Building a Culture of Life with Middle School & High School Students

1 ARCHDIOCESE BUILDING A CULTURE OF LIFE WITH OF BALTIMORE MIDDLE SCHOOL & HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS Respect Life Office Division of Youth and Young Adult Ministry 2 “In this mobilization for a new culture of life no one must feel excluded: everyone has an important role to play. Together with the family, teachers and educators have a particularly valuable contribution to make. Much will depend on them if young people, trained in true freedom, are to be able to preserve for themselves and make known to others new, authentic ideals for life, and if they are to grow in respect for and service to every other person, in the family and in society.” Evangelium Vitae n. 98. 3 Table of Contents Respect Life Prayer 1 Father Damien Lesson Plan 3 October 11 Homily 9 Respect Life Resources 11 Euthanasia/ Assisted Suicide 12 Abortion 14 Poverty 16 Racism 17 Domestic Violence 18 Human Cloning 19 Stem Cell/ Embryo, and Fetal Research 20 Capital Punishment 22 Human Trafficking 24 Dignity of Persons with Disabilities 25 War and Just War 26 Conservation and the Environment 27 Unemployment 28 Homelessness 29 Contraception 30 Nuclear Arms 32 March for Life Lesson Plan 33 Defending the Truth: Lesson in Respect Life Apologetics 38 Preparing for the March for Life 43 Attending the March 47 Culture of Life Day 49 Suggested Activities 50 Respect Life Environment 53 Everyday Respect Life 54 Resources from this document were complied by Dr. Diane Barr, Linda Brenegan, Johanna Coughlin, JD, and D. Scott Miller. Those who contributed to this document include Gail Love, Tony Tamberino, Kristin Witte, and Simei Zhao. -

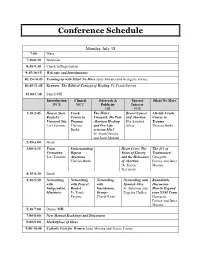

Conference Schedule

Conference Schedule Monday July 18 7:00 Mass 7:30-8:30 Breakfast 8:30-9:30 Check In/Registration 9:45-10:15 Welcome and Introductions 10:15-10:45 Teaming up with Silent No More Janet Morana and Georgette Forney 10:45-11:45 Keynote: The Biblical Concept of Healing Fr. Frank Pavone 12:00-1:30 Lunch MH Introduction Clinical Outreach & Special Silent No More WCR MCC Publicity Interest DR ECR 1:30-2:45 How to Start Crash The Wider Breast Cancer Attend: Crash Rachel’s Course in Vineyard: Do Post- and Abortion Course in Vineyard Site Trauma Abortion Healing Eve Sanchez Trauma Lori Eckstine Theresa and Pro-Life Silver Theresa Burke Burke activism Mix? Fr. Frank Pavone and Janet Morana 2:45-3:00 Break 3:00-4:15 Team Understanding Heart Cries: The The 411 of Formation Repeat Roots of Slavery Testimonies! Lori Eckstine Abortions and the Holocaust Georgette Theresa Burke of Abortion Forney and Janet Dr. Karen Morana Stevensen 4:15-4:30 Break 4:30-5:30 Networking Networking Networking Networking with Roundtable with with Project with Spanish Sites Discussion: Independent Rachel Interdenom. Fr. Salomon and How to Expand Ministries Fr. Frank Groups Eugenia Hadley your SNM Team Pavone Cheryl Ryan Georgette Forney and Janet Morana 5:30-7:00 Dinner MH 7:00-8:00 New Manual Exchange and Discussion 8:00-9:00 Marketplace of Ideas 9:00-10:00 Catholic View for Women Janet Morana and Teresa Tomeo Tuesday July 19 7:30-8:00 Mass with Fr. Frank Pavone or Protestant Service with Cheryl Ryan 8:00-9:00 Breakfast 9:00-9:30 Morning Praise and Announcements 9:30-11:00 Keynote: Media Training Teresa Tomeo Introduction Clinical Outreach & Special Interest Silent No WCR MCC Publicity ECR more DR 11:00-12:00 The Wacky, Contraception: Media Mission, Message Attend: Media The Weird, It’s Influence on and Ministry for Influence on The Implications for the Culture of the Service of the Culture of Unspeakable Rachel’s Death Life Death Theresa and Vineyard Part I Teresa Tomeo Msgr. -

Priests for Life V. Sebelius

Case 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Document 12 Filed 05/14/12 Page 1 of 34 PageID #: 114 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK PRIESTS FOR LIFE, Case No. 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Plaintiff, v. FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, in her official Hon. Frederic Block capacity as Secretary, United States Department of Health and Human Services; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES; HILDA SOLIS, in her official capacity as Secretary, United States Department of Labor; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR; TIMOTHY GEITHNER, in his official capacity as Secretary, United States Department of the Treasury; and UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, Defendants. Plaintiff Priests for Life, by and through undersigned counsel, brings this First Amended Complaint against the above-named Defendants, their employees, agents, and successors in office, and in support thereof alleges the following upon information and belief: INTRODUCTION 1. This is a civil action in which Plaintiff Priests for Life is seeking to protect and defend its fundamental rights to religious liberty and freedom of speech. Priests for Life is challenging certain implementing regulations of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Affordable Care Act”) which require it, as an employer, to provide insurance plans that include coverage for, or access to, contraception, sterilization, abortifacients, and related education and 1 Case 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Document 12 Filed 05/14/12 Page 2 of 34 PageID #: 115 counseling under penalty of federal law. This government mandate violates Priests for Life’s rights to the free exercise of religion and the freedom of speech, it violates the Establishment Clause, and it deprives Priests for Life of the equal protection of the law in violation of the United States Constitution. -

How Law Students and Attorneys Can Help the Pro-Life Movement

AMLR.V5I2.PAVONE.POSTPROOFLAYOUT2.1116 9/8/2008 6:41:20 PM Copyright © 2007 Ave Maria Law Review HOW LAW STUDENTS AND ATTORNEYS CAN HELP THE PRO-LIFE MOVEMENT Fr. Frank Pavone, M.E.V.† I. THE PRIORITY OF THE TASK At their annual meeting in November of 1989, the United States Catholic Bishops unanimously adopted a Resolution on Abortion, which stated in part: “At this particular time, abortion has become the fundamental human rights issue for all men and women of good will.”1 That statement remains true today and has been echoed in numerous subsequent statements from the bishops over the years. No act of violence claims more victims.2 Moreover, no social policy more radically undermines our legal system, turning on its head the very purpose of law. In their 1998 document Living the Gospel of Life, the bishops made this striking statement: “When American political life becomes an experiment on people rather than for and by them, it will no longer be worth conducting. We are arguably moving closer to that day.”3 Pope John Paul II spoke in similarly strong language about the implications of the failure of the state to protect the right to life in his encyclical The Gospel of Life, which is a seminal document for the pro-life movement: † National Director, Priests for Life. In 2005, Fr. Pavone established the Missionaries of the Gospel of Life (M.E.V.), a new community within the Catholic Church that accepts and trains its own seminarians to be ordained for the full-time, pro-life work of Priests for Life. -

The Knowledge

Conscience and Complicity: Assessing Pleas for Religious Exemptions in Hobby Lobby’s Wake Amy J. Sepinwall† In the paradigmatic case of conscientious objection, the objector claims that his religion forbids him from actively participating in a wrong (for example, by fighting in a war). In the religious challenges to the Affordable Care Act’s employer mandate, on the other hand, employers claim that their religious convictions forbid them from merely subsidizing insurance through which their employees might commit a wrong (for example, by using contraception). The understanding of com- plicity underpinning these challenges is vastly more expansive than the standard that legal doctrine or moral theory contemplates. Courts routinely reject claims of conscientious objection to taxes that fund military initiatives or to university fees that support abortion services. In Hobby Lobby, however, the Supreme Court took the corporate owners at their word: the mere fact that Hobby Lobby believed that it would be complicit, no matter how idiosyncratic its belief, sufficed to qualify it for an exemption. In this way, the Court made elements of an employee’s health-care package the “boss’s business” (to borrow from the nickname of the Democrats’ pro- posed bill to overturn Hobby Lobby). Much of the critical reaction to Hobby Lobby focuses on the issue of corporate rights of religious freedom. Yet this issue is a red herring. The deeper concerns that Hobby Lobby raises—about whether employers may now refuse, on religious grounds, to subsidize other forms of health coverage (for example, blood transfu- sions or vaccinations) or to serve customers whose lifestyles they deplore (for exam- ple, gays and lesbians)—do not turn on the organizational form that the employer † Assistant Professor, Department of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. -

Original Letter Sent from Pro-Life Leaders to the Pope

Priests for Life is a recognized Catholic association and a 501(c)(3) corporation whose mission is to end abortion and euthanasia. With a full-time staff of over 60 people, it is a family of ministries, encompassing Deacons for Life, Seminarians for Life, Rachel’s Vineyard, the Silent No More Awareness Campaign, Gospel of Life Ministries, and more. Ecclesiastical Authority His Eminence Cardinal Timothy Dolan Archbishop of New York Our Pastoral Team (Partial list) Fr. Frank A. Pavone National Director and Chairman Fr. Denis G. Wilde, OSA Associate Director Fr. Walter Quinn, OSA Priest Associate Fr. Victor Salomón Director, Hispanic Outreach Assisting God’s People to Proclaim, Celebrate, and Serve the Gospel of Life. Msgr. Michael T. Mannion Pastoral Consultant August 31, 2014 Fr. Scott Daniels, OP Pastoral Consultant His Holiness Pope Francis Janet A. Morana Executive Director Vatican City State Co-Founder, Silent No More Awareness Campaign Dr. Alveda King Your Holiness, Director, African-American Outreach Dr. Theresa and Kevin Burke It is with joy and encouragement that we, the leaders of national pro-life Founders, Rachel’s Vineyard Ministries organizations in the United States, have received the news of the various Mr. Bryan Kemper Director, Youth Outreach initiatives of the Catholic Church this year and next year in favor of the Advisory Board of Bishops (Partial list) family. His Eminence Cardinal Christoph Schönborn Archbishop of Vienna The Extraordinary Synod of Bishops, to meet later this year, will address His Eminence Renato Cardinal Martino President Emeritus, Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Challenges of the Family in the Context of Evangelization. -

The Catholic Voice Is on Facebook

The Catholic Voice is on Facebook VOL. 57, NO. 1 DIOCESE OF OAKLAND JANUARY 7, 2019 www.catholicvoiceoakland.org Serving the East Bay Catholic Community since 1963 Copyright 2019 Walk for Life Jan. 26 in SF Staff report Join tens of thousands of pro-lifers of all ages, races and religions at the 15th annual Walk for Life West Coast on Jan. 26 in San Francisco. At the 12:30 p.m. rally at Civic Center Plaza, Rev. Walter Hoye, founder and president of the Issues4Life Foundation, whose unjust imprisonment for exercising his First Amendment rights made him a worldwide hero to the pro-life movement, will be among the speakers. Hoye will be joined by Rev. Shenan Boquet, president of Human Life International, who travels the world spreading the Gospel of Life; pro-life and pro-chastity speaker Patricia Sandoval, who will share her gripping story of the journey from pain and fear to hope and life; and Abby Johnson, a former Planned Parenthood worker who crossed the line to join the pro-life movement. (Continued on Page 11.) MICHELE JURICH/THE CATHOLIC VOICE MICHELE JURICH/THE CATHOLIC The gymnasium at Santa Rita Jail in Dublin was transformed: At the basketball court’s baseline, a folding table, covered with a white cloth, and anchored by a tabletop crucifix, became the altar. ‘You really feel the presence of Christ here’ By Michele Jurich Rev. Lawrence D’Anjou, pastor of St. In his homily, Bishop Barber encour- Staff writer Raymond Church in Dublin, in whose bound- aged the men to look beyond getting out For one hour on a Saturday morning in aries the jail stands; Revs. -

Evangelium Vitae Today How Conservative Forces Are Using the 1995 Papal Encyclical to Reshape Public Policy in Latin America by Juan Marco Vaggione O R E M O R

Evangelium Vitae Today how conservative forces are using the 1995 papal encyclical to reshape public policy in latin america By Juan Marco Vaggione o r e m o r y r n e h / s r e t u e r © Cardinal Norberto Rivera Carrera of Mexico (L) gives a plate with an image representing the Holy Family to Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone during the VI World Meeting of Families in Mexico City, Jan. 16, 2009. onservative catholic or so, the manner in which these activists women’s rights and reproductive rights activists have historically played work has been transformed, pushed in advocates have had in placing their a central role in shaping public large part by the Vatican. In large demands on national and global public policy in most Latin American measure, this transformation has been agendas. Far from retreating in the face Ccountries. In the last decade developed to counter the successes that of this onslaught, conservative religious activists have strategically adapted to the new context so as to continue influencing juan marco vaggione is a researcher at the Argentinean National Scientific and Technical public policy and legislation. What’s new Research Council and a professor of Sociology at the School of Law, National University of Córdoba. His main research interests are religion and politics in Latin America, especially as they impact on is not the content of their beliefs, which sexual and reproductive rights. He works closely with Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir in Argentina. continue to be strongly patriarchal and vol. xxxi—no. -

Pro-Woman Framing in the Pro-Life Movement

Fighting for Life: Pro-Woman Framing in the Pro-life Movement Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alexa J. Trumpy Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Andrew Martin, Advisor Vincent Roscigno Liana Sayer Copyrighted by Alexa J. Trumpy 2011 Abstract How do marginal actors change hearts and minds? Social movement scholars have long recognized that institutional outsiders target a range of potential allies to press their agenda. While much of the movement research historically privileged formal political activities in explaining social change, understanding the way actors draw upon culture and identity to garner wider support for a variety of social, political, and economic causes has become increasingly important. Ultimately, research that incorporates political process theories with the seemingly dichotomous notions of cultural and collective identity is especially valuable. To better understand how movement actors achieve broad change, I draw on recent attempts to examine how change occurs in fields. I argue it is necessary to examine how a field’s structural and cultural components, as well as the more individual actions, resources, rhetoric, and ideologies of relevant actors, interact to affect field change or maintain stasis. This research does so through an analysis of the current debate over abortion in America, arguably the most viciously divisive religious, moral, political, and legal issue since slavery. Over the past four decades, the American abortion debate has been glibly characterized as fight between the rights of two groups: women and fetuses, with pro-choice groups championing the rights of the former and pro-life groups the latter.