The Prochoice Religious Community May Be the Future of Reproductive Rights, Access, and Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Women Redesign Catholicism: an Essay in Honor of Maria Jose Rosado Nunez

CATHOLIC WOMEN REDESIGN CATHOLICISM: AN ESSAY IN HONOR OF MARIA JOSE ROSADO NUNEZ Mary Elizabeth Hunt* ABSTRACT This essay explores how Catholic women have changed Catholicism as a culture, if not so much the institutional church, in the years be- tween 1970 and 2020. Catholic women have not endeared ourselves to Catholic hierarchs; in fact many dislike and fear us. But we have saved lives, spiritual as well as physical, by providing solid opposition and creative alternatives to the institutional church. A redesign of Catholicsm begins with the culture and ethos. Catholic women en- vision it as a global movement rooted in particular cultures, united by values of love and justice, open to the wisdom of many religious traditions, and structured to provide ministry and meaning through cooperative, horizontally organized communities. While there has been progress, more work remains to be done. INTRODUCTION Maria José Rosado Nunez is a deeply respected and beloved col- league in struggles for women’s well-being, especially in the area of reproductive justice. Her decades of creative, fearless, and pioneering work are a legacy for Brazilians as well as for other justice-seekers throughout the world. As a highly skilled sociologist, someone who is deeply informed on theological, philosophical, artistic, and cultural issues, Zeca, as she is known to all, is a unique and valued collaborator. We met decades ago through Catholics for a Free Choice as it was known in those days, as well as in international feminist theological circles. I have had the privilege of collaborating with her and the won- derful team at Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir over the years. -

Catholics for Choice

Nos. 19-431 and 19-454 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LITTLE SISTERS OF THE POOR SAINTS PETER AND PAUL HOME, Petitioner, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al., Respondents. DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, et al., Petitioners, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al., Respondents. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRcuIT BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE CATHOLICS FOR CHOICE, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN, THE CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS, WOMEN OF REFORM JUDAISM, JEWISH WOMEN INTERNATIONAL, KESHET, MUSLIMS FOR PROGRESSIVE VALUES, RABBINICAL ASSEMBLY, RECONSTRUCTING JUDAISM, SOCIETY FOR HUMANISTIC JUDAISM, T’RUAH: THE RABBINIC CALL FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, AND UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS B. JESSIE HILL Counsel of Record CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 11075 East Boulevard Cleveland, Ohio 44106 (216) 368-0553 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae 295696 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................. ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST .......................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................... 4 ARGUMENT ...................................................... 7 I. PEOPLE OF DIVERSE FAITHS SUPPORT ACCESS TO CONTRACEPTION ............................... 7 II. THE CONTRACEPTIVE BENEFIT SERVES COMPELLING GOVERNMENT INTERESTS AND THE REGULATIONS THREATEN IRREPARABLE HARM ....................... 14 CONCLUSION ................................................ 22 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet, 512 U.S. 687 (1994) .............................................. 15 Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. 682 (2014) .............................................. 16 Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005) .............................................. 15 Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) .............................................. 16 Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc., 472 U.S. 703 (1985) ............................................. -

Family & Prolife News Briefs

Family & ProLife News Briefs October 2020 ProLifers Hopeful .... and Determined In the Culture In Public Policy 1. Many programs are expanding. For example, 1. Political party platforms are focusing more than 40 Days for Life is now active in hundreds of U.S. ever on life issues. The Libertarian platform states cities and is going on right now through Nov. 1st. life and abortion issues are strictly private matters. People stand vigil, praying outside of abortion The Democrat platform says “every woman should clinics. Also, the nationwide one-day Life Chain have access to ... safe and legal abortion.” The brings out thousands of people to give silent Republican platform states: “we assert the sanctity witness to our concern for a culture of life. And for of human life and ...the unborn child has a those who have taken part in an abortion, the fundamental right to life which cannot be infringed.” Church offers hope through Rachel’s Vineyard, a Respect life groups such as Priests for Life, & program of forgiveness and healing. the Susan B. Anthony List and others are seeking Another example: the Archdiocese of Miami’s election volunteers to get out the vote. Log onto Respect Life Ministry has been offering a monthly their websites if you might like to help. webinar as part of the U.S. Bishops theme of On Sept. 20th a full page ad in the NYTimes was "Walking with Moms: A Year of Service." Septem- signed by hundreds of Democrat leaders urging the ber’s webinar was How to Be a Pregnancy Center party to soften its stance towards abortion. -

Documents/Hf P- Vi Enc 25071968 Humanae- Vitae.Html

Nos. 18-1323, 18-1460 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JUNE MEDICAL SERVICES L.L.C., et al., Petitioners, v. DR. REBEKAH GEE, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, Respondent. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– DR. REBEKAH GEE, Secretary, Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, Cross-Petitioner, v. JUNE MEDICAL SERVICES L.L.C., et al., Cross-Respondents. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRcuIT AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF CATHOLICS FOR CHOICE, NATIONAL COUncIL OF JEWISH WOMEN, METHODIST FEDERATION FOR SOCIAL AcTION, MUSLIMS FOR PROGRESSIVE VALUES, PRESBYTERIANS AFFIRMING REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE, RELIGIOUS COALITION FOR REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE, RELIGIOUS InSTITUTE, UnION FOR REFORM JUDAISM, UnITED CHURCH OF CHRIST, AND 19 OTHER ORGANIZATIONS, SUppORTING PETITIONERS EUGENE M. GELERNTER Counsel of Record PATTERSON BELKNAP WEbb & TYLER LLP 1133 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10036 (212) 336-2553 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae (For Continuation of Appearances See Inside Cover) BARBARA MULLIN KEVIN OPOKU-GYAMFI PATTERSON BELKNAP WEbb & TYLER LLP 1133 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10036 (212) 336-2553 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................. 8 ARGUMENT .......................................................... 10 I. RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS RECOGNIZE WOMEN’S MORAL RIGHT TO DECIDE WHETHER TO TERMINATE A PREGNANCY ............. 10 II. WOMEN’S MORAL RIGHT TO TERMINATE A PREGNANCY SHOULD NOT BE VITIATED BY UNNECESSARY IMPEDIMENTS ON ACCESS TO SAFE AND AFFORDABLE ABORTION .................. 21 III. ACT 620 INJURES WOMEN’S HEALTH AND DIGNITY BY INCREASING COSTS AND DECREASING ACCESS TO SAFE ABORTION CARE ................................... 26 CONCLUSION ...................................................... 31 i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Eisenstadt v. -

The Reconciliation of Religion and Reproductive Rights: Catholicism’S Role in the American Abortion Controversy

Hannah Lynch Culture, Cognition & Justice Psychology Seminar The Reconciliation of Religion and Reproductive Rights: Catholicism’s Role in the American Abortion Controversy Abstract This project explores the cultural and cognitive effects of religious faith on psychological conception of justice in the realm of reproductive rights. For the sake of specifying my research question, I confine the scope of my research to Catholicism’s influence on opinion about abortion. To further narrow the radius of my research, I restrict my context to Catholicism’s influence in the United States due to the increasing attention to and division over abortion in America since Trump’s election. In this paper, I draw on psychological, theological, and statistical sources to identify which conditions enable individuals to reconcile Catholic values with permission of abortion. Paper Given my personal passion for reproductive rights and the political prominence of the pro-choice v. pro-life debate, I see the topic of abortion both relevant and fascinating to study. In this research paper, I analyze the cultural and cognitive influences Catholicism may have on people’s perceptions of abortion. More specifically, I aim to determine if and under which conditions individuals can psychologically reconcile Catholic doctrines to permiss abortion. To understand the framework in which Catholicism affects individuals’ conceptions of abortion, I conducted preliminary research on how religion influences cognition in general. Although religion is commonly recognized as expansively influential in history and politics, it is rarely acknowledged as an influential factor in cognition. According to a 2011 study by Shariff at the University of British Columbia, nonetheless, spirituality can have significant impacts on mental processes. -

Priests for Life Defies Constitution and Conscience

OPPOSITION NOTES AN INVESTIGATIVE SERIES ON THOSE WHO OPPOSE WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH Faithless Politics: Priests for Life Defies Constitution and Conscience INTRODUCTION riests for Life national director Frank Pavone has spent more than 15 years trying vainly to grow his Catholic antichoice group into the mass clerical movement P envisioned in its rhetoric, only to find himself banished to a Texan wasteland. In a country with some 40,000 Catholic priests, Priests for Life (PFL) has never claimed more than 5,000 members—and quietly stopped counting some time around the turn of the 21st century. Unapologetic electoral campaigning, and unabashed cooperation with the most militant antichoice figures, have not brought PFL membership numbers to match the New York priest’s ambitions. Pavone’s nonprofit says it is “for everyone who wants to stop abortion and euthanasia,” “not an association that seeks to be some sort of separate and elite group of priests who claim to be more pro-life than all the rest”1; it boasts the church hierarchy’s approval, strict orthodoxy and a board of archbishops and cardinals. Even by PFL’s own optimistic estimates, however, Pavone appears never to Pavone has always personalized the PFL message and have attracted a membership of more than one in five US priests. His reaction has been to all image, selling himself—often with large photos of himself but give up on the existing priesthood, which he on PFL billboards—much as a candidate for office might do. regularly castigates as too timid on abortion, and to seek to mold young priests in his image at his new Texas refuge. -

![[NOT YET SCHEDULED for ORAL ARGUMENT] No. 13-5069 ______](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9144/not-yet-scheduled-for-oral-argument-no-13-5069-1339144.webp)

[NOT YET SCHEDULED for ORAL ARGUMENT] No. 13-5069 ______

USCA Case #13-5069 Document #1441480 Filed: 06/14/2013 Page 1 of 53 [NOT YET SCHEDULED FOR ORAL ARGUMENT] No. 13-5069 __________________________________________________________________ In the United States Court Of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit __________________________________________________________________ Francis A. Gilardi, Jr., et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. United States Department of Health and Human Services, et al., Defendants-Appellees. _________________________________________________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Judge Emmet G. Sullivan __________________________________________________________________ Brief In Support of Appellees and Affirmance by Amici Curiae Americans United for Separation of Church and State; American Civil Liberties Union; Anti-Defamation League; Catholics for Choice; Central Conference of American Rabbis; Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Inc.; Hindu American Foundation; Interfaith Alliance Foundation; National Coalition of American Nuns; National Council of Jewish Women; Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice; Religious Institute; Union for Reform Judaism; Unitarian Universalist Women’s Federation; and Women of Reform Judaism __________________________________________________________________ Daniel Mach ([email protected]) Ayesha N. Khan ([email protected]) AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES Gregory M. Lipper ([email protected]) UNION FOUNDATION AMERICANS UNITED FOR SEPARATION 915 15th Street, NW OF CHURCH AND STATE -

Fr. Frank Pavone of Priests for Life on the Consistent Life Ethic

MISSION: We are committed to the protection of life, which is threatened in today's world by war, abortion, poverty, racism, capital punishment, and euthanasia. We believe that these issues are linked under a “consistent ethic of life.” We challenge those working on all or some of these issues to maintain a cooperative spirit of peace, reconciliation, and respect in protecting the unprotected. About Us Consistent Life is a network uniting those who support the consistent life ethic (CLE) of reverence for all life. Our work involves spreading the vision throughout our nation and world by placing ads, attending and presenting at conferences, and producing free literature showing that consistent opposition to killing is a stance of many well-known anti-abortion and anti-war activists and faith groups. We keep the consistent pro-life community updated on relevant issues, news, and action opportunities via our newsletter (twice a year) and one-page e-letter (weekly). We are trying to achieve a revolution in thinking and feeling; an affirmation of peace and nonviolence; recognition of the value of the life, happiness, and welfare of every person; and all the political and structural changes that will bring this about. FAQ Q: Are you a religious or partisan organization? A: No. The majority of our member organizations and members are Christian, but we welcome good people of any or no faith. We are not affiliated with any political party and do not endorse political candidates. We seek to broaden the pro-life movement in order to strengthen protection for life. Q: Are you “really” pro-life? A: Yes. -

Building a Culture of Life with Middle School & High School Students

1 ARCHDIOCESE BUILDING A CULTURE OF LIFE WITH OF BALTIMORE MIDDLE SCHOOL & HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS Respect Life Office Division of Youth and Young Adult Ministry 2 “In this mobilization for a new culture of life no one must feel excluded: everyone has an important role to play. Together with the family, teachers and educators have a particularly valuable contribution to make. Much will depend on them if young people, trained in true freedom, are to be able to preserve for themselves and make known to others new, authentic ideals for life, and if they are to grow in respect for and service to every other person, in the family and in society.” Evangelium Vitae n. 98. 3 Table of Contents Respect Life Prayer 1 Father Damien Lesson Plan 3 October 11 Homily 9 Respect Life Resources 11 Euthanasia/ Assisted Suicide 12 Abortion 14 Poverty 16 Racism 17 Domestic Violence 18 Human Cloning 19 Stem Cell/ Embryo, and Fetal Research 20 Capital Punishment 22 Human Trafficking 24 Dignity of Persons with Disabilities 25 War and Just War 26 Conservation and the Environment 27 Unemployment 28 Homelessness 29 Contraception 30 Nuclear Arms 32 March for Life Lesson Plan 33 Defending the Truth: Lesson in Respect Life Apologetics 38 Preparing for the March for Life 43 Attending the March 47 Culture of Life Day 49 Suggested Activities 50 Respect Life Environment 53 Everyday Respect Life 54 Resources from this document were complied by Dr. Diane Barr, Linda Brenegan, Johanna Coughlin, JD, and D. Scott Miller. Those who contributed to this document include Gail Love, Tony Tamberino, Kristin Witte, and Simei Zhao. -

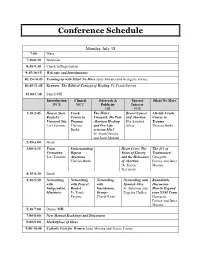

Conference Schedule

Conference Schedule Monday July 18 7:00 Mass 7:30-8:30 Breakfast 8:30-9:30 Check In/Registration 9:45-10:15 Welcome and Introductions 10:15-10:45 Teaming up with Silent No More Janet Morana and Georgette Forney 10:45-11:45 Keynote: The Biblical Concept of Healing Fr. Frank Pavone 12:00-1:30 Lunch MH Introduction Clinical Outreach & Special Silent No More WCR MCC Publicity Interest DR ECR 1:30-2:45 How to Start Crash The Wider Breast Cancer Attend: Crash Rachel’s Course in Vineyard: Do Post- and Abortion Course in Vineyard Site Trauma Abortion Healing Eve Sanchez Trauma Lori Eckstine Theresa and Pro-Life Silver Theresa Burke Burke activism Mix? Fr. Frank Pavone and Janet Morana 2:45-3:00 Break 3:00-4:15 Team Understanding Heart Cries: The The 411 of Formation Repeat Roots of Slavery Testimonies! Lori Eckstine Abortions and the Holocaust Georgette Theresa Burke of Abortion Forney and Janet Dr. Karen Morana Stevensen 4:15-4:30 Break 4:30-5:30 Networking Networking Networking Networking with Roundtable with with Project with Spanish Sites Discussion: Independent Rachel Interdenom. Fr. Salomon and How to Expand Ministries Fr. Frank Groups Eugenia Hadley your SNM Team Pavone Cheryl Ryan Georgette Forney and Janet Morana 5:30-7:00 Dinner MH 7:00-8:00 New Manual Exchange and Discussion 8:00-9:00 Marketplace of Ideas 9:00-10:00 Catholic View for Women Janet Morana and Teresa Tomeo Tuesday July 19 7:30-8:00 Mass with Fr. Frank Pavone or Protestant Service with Cheryl Ryan 8:00-9:00 Breakfast 9:00-9:30 Morning Praise and Announcements 9:30-11:00 Keynote: Media Training Teresa Tomeo Introduction Clinical Outreach & Special Interest Silent No WCR MCC Publicity ECR more DR 11:00-12:00 The Wacky, Contraception: Media Mission, Message Attend: Media The Weird, It’s Influence on and Ministry for Influence on The Implications for the Culture of the Service of the Culture of Unspeakable Rachel’s Death Life Death Theresa and Vineyard Part I Teresa Tomeo Msgr. -

Priests for Life V. Sebelius

Case 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Document 12 Filed 05/14/12 Page 1 of 34 PageID #: 114 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK PRIESTS FOR LIFE, Case No. 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Plaintiff, v. FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, in her official Hon. Frederic Block capacity as Secretary, United States Department of Health and Human Services; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES; HILDA SOLIS, in her official capacity as Secretary, United States Department of Labor; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR; TIMOTHY GEITHNER, in his official capacity as Secretary, United States Department of the Treasury; and UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, Defendants. Plaintiff Priests for Life, by and through undersigned counsel, brings this First Amended Complaint against the above-named Defendants, their employees, agents, and successors in office, and in support thereof alleges the following upon information and belief: INTRODUCTION 1. This is a civil action in which Plaintiff Priests for Life is seeking to protect and defend its fundamental rights to religious liberty and freedom of speech. Priests for Life is challenging certain implementing regulations of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Affordable Care Act”) which require it, as an employer, to provide insurance plans that include coverage for, or access to, contraception, sterilization, abortifacients, and related education and 1 Case 1:12-cv-00753-FB-RER Document 12 Filed 05/14/12 Page 2 of 34 PageID #: 115 counseling under penalty of federal law. This government mandate violates Priests for Life’s rights to the free exercise of religion and the freedom of speech, it violates the Establishment Clause, and it deprives Priests for Life of the equal protection of the law in violation of the United States Constitution. -

How Law Students and Attorneys Can Help the Pro-Life Movement

AMLR.V5I2.PAVONE.POSTPROOFLAYOUT2.1116 9/8/2008 6:41:20 PM Copyright © 2007 Ave Maria Law Review HOW LAW STUDENTS AND ATTORNEYS CAN HELP THE PRO-LIFE MOVEMENT Fr. Frank Pavone, M.E.V.† I. THE PRIORITY OF THE TASK At their annual meeting in November of 1989, the United States Catholic Bishops unanimously adopted a Resolution on Abortion, which stated in part: “At this particular time, abortion has become the fundamental human rights issue for all men and women of good will.”1 That statement remains true today and has been echoed in numerous subsequent statements from the bishops over the years. No act of violence claims more victims.2 Moreover, no social policy more radically undermines our legal system, turning on its head the very purpose of law. In their 1998 document Living the Gospel of Life, the bishops made this striking statement: “When American political life becomes an experiment on people rather than for and by them, it will no longer be worth conducting. We are arguably moving closer to that day.”3 Pope John Paul II spoke in similarly strong language about the implications of the failure of the state to protect the right to life in his encyclical The Gospel of Life, which is a seminal document for the pro-life movement: † National Director, Priests for Life. In 2005, Fr. Pavone established the Missionaries of the Gospel of Life (M.E.V.), a new community within the Catholic Church that accepts and trains its own seminarians to be ordained for the full-time, pro-life work of Priests for Life.