Cue Switching in the Perception of Approximants: Evidence from Two English Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 the BASIC SOUNDS of ENGLISH 1. STOPS a Stop Consonant Is Produced with a Complete Closure of Airflow

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology THE BASIC SOUNDS OF ENGLISH 1. STOPS A stop consonant is produced with a complete closure of airflow in the vocal tract; the air pressure has built up behind the closure; the air rushes out with an explosive sound when released. The term plosive is also used for oral stops. ORAL STOPS: e.g., [b] [t] (= plosives) NASAL STOPS: e.g., [m] [n] (= nasals) There are three phases of stop articulation: i. CLOSING PHASE (approach or shutting phase) The articulators are moving from an open state to a closed state; ii. CLOSURE PHASE (= occlusion) Blockage of the airflow in the oral tract; iii. RELEASE PHASE Sudden reopening; it may be accompanied by a burst of air. ORAL STOPS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL STOPS: The blockage is made with the two lips. spot [p] voiceless baby [b] voiced 1 b. ALVEOLAR STOPS: The blade (or the tip) of the tongue makes a closure with the alveolar ridge; the sides of the tongue are along the upper teeth. lamino-alveolar stops or Check your apico-alveolar stops pronunciation! stake [t] voiceless deep [d] voiced c. VELAR STOPS: The closure is between the back of the tongue (= dorsum) and the velum. dorso-velar stops scar [k] voiceless goose [g] voiced 2. NASALS (= nasal stops) The air is stopped in the oral tract, but the velum is lowered so that the airflow can go through the nasal tract. All nasals are voiced. NASALS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL NASAL: made [m] b. ALVEOLAR NASAL: need [n] c. -

Manner of Articulation

An Animated and Narrated Glossary of Terms used in Linguistics presents Manner of Articulation Articulators Slide 2 Page 1 Manner of Articulation • The manner of articulation refers to the way airflow is controlled in the production of a phone (i.e. a linguistic sound). Slide 3 Manner of Articulation on the IPA Chart Plosive Nasal Trill Tap or Flap Fricative Lateral fricative Approximant Lateral approximant Manner of articulation Slide 4 Page 2 Plosive p Plosives require total obstruction of airflow. Slide 5 Nasal n Nasals require air to flow out of the nose. Slide 6 Page 3 Trill r Trills are made by rapid succession of contact between articulators that obstruct airflow. Slide 7 Tap or Flap A tap or flap is like trill, except that there is only one rapid contact between the articulators. There is some difference between tap and flap, but we shall not pursue that here. Slide 8 Page 4 Fricative f A fricative is formed when the stricture is very narrow (but without total closure) so that when air flows out, a hissing noise is made. Slide 9 Approximant An approximant is a phone made when the obstruction of airflow does not produce any audible friction. Slide 10 Page 5 Lateral l A lateral is made when air flows out of the sides of the mouth. Slide 11 Note • In this presentation, we have concentrated on the pulmonic consonants, but manners of articulation may be used to describe vowels and other linguistic sounds as well. Slide 12 Page 6 The End Wee, Lian-Hee and Winnie H.Y. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

![A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0716/a-sociophonetic-study-of-the-metropolitan-french-r-linguistic-factors-determining-rhotic-variation-a-senior-honors-thesis-970716.webp)

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Sarah Elyse Little The Ohio State University June 2012 Project Advisor: Professor Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza, Department of Spanish and Portuguese ii ABSTRACT Rhotic consonants are subject to much variation in their production cross-linguistically. The Romance languages provide an excellent example of rhotic variation not only across but also within languages. This study explores rhotic production in French based on acoustic analysis and considerations of different conditioning factors for such variation. Focusing on trills, previous cross-linguistic studies have shown that these rhotic sounds are oftentimes weakened to fricative or approximant realizations. Furthermore, their voicing can also be subject to variation from voiced to voiceless. In line with these observations, descriptions of French show that its uvular rhotic, traditionally a uvular trill, can display all of these realizations across the different dialects. Focusing on Metropolitan French, i.e., the dialect spoken in Paris, Webb (2009) states that approximant realizations are preferred in coda, intervocalic and word-initial positions after resyllabification; fricatives are more common word-initially and in complex onsets; and voiceless realizations are favored before and after voiceless consonants, with voiced productions preferred elsewhere. However, Webb acknowledges that the precise realizations are subject to much variation and the previous observations are not always followed. Taking Webb’s description as a starting point, this study explores the idea that French rhotic production is subject to much variation but that such variation is conditioned by several factors, including internal and external variables. -

UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Turbulence & Phonology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4kp306rx Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 4(4) ISSN 2768-5047 Authors Ohala, John J Solé, Maria-Josep Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/P74kp306rx eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2008) Turbulence & Phonology John J. Ohala* & Maria-Josep Solé # *Department of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley [email protected] #Department of English, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain [email protected] In this paper we aim to provide an account of some of the phonological patterns involving turbulent sounds, summarizing material we have published previously and results from other investigators. In addition, we explore the ways in which sounds pattern, combine, and evolve in language and how these patterns can be derived from a few physical and perceptual principles which are independent from language itself (Lindblom 1984, 1990a) and which can be empirically verified (Ohala and Jaeger 1986). This approach should be contrasted with that of mainstream phonological theory (i.e., phonological theory within generative linguistics) which primarily considers sound structure as motivated by ‘formal’ principles or constraints that are specific to language, rather than relevant to other physical or cognitive domains. For this reason, the title of this paper is meant to be ambiguous. The primary sense of it refers to sound patterns in languages involving sounds with turbulence, e.g., fricatives and stops bursts, but a secondary meaning is the metaphorical turbulence in the practice of phonology over the past several decades. -

Arabic and English Consonants: a Phonetic and Phonological Investigation

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Arabic and English Consonants: A Phonetic and Phonological Investigation Mohammed Shariq College of Science and Arts, Methnab, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Received: 18/07/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Accepted: 15/09/2015 Abstract This paper is an attempt to investigate the actual pronunciation of the consonants of Arabic and English with the help of phonetic and phonological tools like manner of the articulation, point of articulation, and their distribution at different positions in Arabic and English words. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the consonants of Arabic and English can be useful in overcoming the hindrances that confront the Arab EFL learners. The larger aim is to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learning outcomes. Keywords: Phonetics, Phonology, Pronunciation, Arabic Consonants, English Consonants, Manner of articulation, Point of articulation 1. Introduction Cannorn (1967) and Ekundare (1993) define phonetics as sounds which is the basis of human speech as an acoustic phenomenon. It has a source of vibration somewhere in the vocal apparatus. According to Varshney (1995), Phonetics is the scientific study of the production, transmission and reception of speech sounds. It studies the medium of spoken language. On the other hand, Phonology concerns itself with the evolution, analysis, arrangement and description of the phonemes or meaningful sounds of a language (Ramamurthi, 2004). -

Websites for IPA Practice

IPA review Websites for IPA practice • http://languageinstinct.blogspot.com/2006/10/stress-timed-rhythm-of-english.html • http://ipa.typeit.org/ • http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/phonetics.html • http://phonetics.ucla.edu/vowels/contents.html • http://accent.gmu.edu/browse_language.php • http://isg.urv.es/sociolinguistics/varieties/index.html • http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/english/frameset.html • http://usefulenglish.ru/phonetics/practice-vowel-contrast • http://www.unc.edu/~jlsmith/pht-url.html#(0) • http://www.agendaweb.org/phonetic.html • http://www.anglistik.uni-bonn.de/samgram/phonprac.htm • http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/phonetics/phonetics.html • http://www.englishexercises.org/makeagame/viewgame.asp?id=4767 • http://www.tedpower.co.uk/phonetics.htm • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speech_perception • http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/sounds/changing-voices/ • http://www.mta.ca/faculty/arts-letters/mll/linguistics/exercises/index.html#phono • http://cla.calpoly.edu/~jrubba/phon/weeklypractice.html • http://amyrey.web.unc.edu/classes/ling-101-online/practice/phonology-practice/ Articulatory description of consonant sounds • State of glottis (voiced or voiceless) • Place of articulation (bilabial, alveolar, etc.) • Manner of articulation (stop, fricative, etc.) Bilabial [p] pit [b] bit [m] mit [w] wit Labiodental [f] fan [v] van Interdental “th” [θ] thigh [ð] thy Alveolar [t] tip [d] dip [s] sip [z] zip [n] nip [l] lip [ɹ] rip Alveopalatal [tʃ] chin [dʒ] gin [ʃ] shin [ʒ] azure Palatal [j] yes Velar [k] call [g] guy [ŋ] sing -

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (Revised to 2015)

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (revised to 2015) CONSONANTS (PULMONIC) © 2015 IPA Bilabial Labiodental Dental Alveolar Postalveolar Retroflex Palatal Velar Uvular Pharyngeal Glottal Plosive Nasal Trill Tap or Flap Fricative Lateral fricative Approximant Lateral approximant Symbols to the right in a cell are voiced, to the left are voiceless. Shaded areas denote articulations judged impossible. CONSONANTS (NON-PULMONIC) VOWELS Clicks Voiced implosives Ejectives Front Central Back Close Bilabial Bilabial Examples: Dental Dental/alveolar Bilabial Close-mid (Post)alveolar Palatal Dental/alveolar Palatoalveolar Velar Velar Open-mid Alveolar lateral Uvular Alveolar fricative OTHER SYMBOLS Open Voiceless labial-velar fricative Alveolo-palatal fricatives Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel. Voiced labial-velar approximant Voiced alveolar lateral flap Voiced labial-palatal approximant Simultaneous and SUPRASEGMENTALS Voiceless epiglottal fricative Primary stress Affricates and double articulations Voiced epiglottal fricative can be represented by two symbols Secondary stress joined by a tie bar if necessary. Epiglottal plosive Long Half-long DIACRITICS Some diacritics may be placed above a symbol with a descender, e.g. Extra-short Voiceless Breathy voiced Dental Minor (foot) group Voiced Creaky voiced Apical Major (intonation) group Aspirated Linguolabial Laminal Syllable break More rounded Labialized Nasalized Linking (absence of a break) Less rounded Palatalized Nasal release TONES AND WORD ACCENTS Advanced Velarized Lateral release LEVEL CONTOUR Extra Retracted Pharyngealized No audible release or high or Rising High Falling Centralized Velarized or pharyngealized High Mid rising Mid-centralized Raised ( = voiced alveolar fricative) Low Low rising Syllabic Lowered ( = voiced bilabial approximant) Extra Rising- low falling Non-syllabic Advanced Tongue Root Downstep Global rise Rhoticity Retracted Tongue Root Upstep Global fall Typeface: Doulos SIL . -

Kejom (Babanki)

UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2018) Kejom (Babanki) Matthew Faytak University of California, Berkeley and University of California, Los Angeles [email protected] Pius W. Akumbu University of Buea [email protected] > Kejom [k`9dZ´Om], the preferred autonym for the language more commonly known as Babanki, is a Central Ring Grassfields Bantu language (ISO 693-3: [bbk]) spoken in the Northwest Region of Cameroon (Hyman, 1980; Simons and Fennig, 2017; Hammarstrom¨ et al., 2017). The lan- > guage is spoken mainly in two settlements, Kejom Ketinguh [k`9dZ´OmŤk´9t´ıNg`uP] and Kejom Keku > [k`9dZ´OmŤk´9k`u], also known as Babanki Tungoh and Big Babanki, respectively (Figure 1), but also to some extent in diaspora communities outside of Cameroon. Simons and Fennig (2017) state that the number of speakers is increasing; however, the figure of 39,000 speakers they provide likely overestimates the number of fluent speakers in diaspora communities. The two main settlements’ dialects exhibit slight phonetic, phonological, and lexical differences but are mutually intelligible. The variety of Kejom described here is the Kejom Ketinguh variant spoken by the second author. Kejom Keku Sparsely populated Bambili Kejom Ketinguh Bamenda Bamenda Yaounde Figure 1: Kejom-speaking areas (right, shaded) within Cameroon (left). Map generated using ggmap in R (Kahle and Wickham, 2013). Most speakers of Kejom also speak Cameroonian Pidgin English, which is increasingly used in all domains, even in the home (Akumbu and Wuchu, 2015). Some speakers in Kejom Keku are also proficient in Kom, a neighboring Central Ring language, depending on their level of engagement with Kom speakers nearby; speakers located in Francophone areas of Cameroon may also speak French. -

2 the Sounds of Language: Consonants

Week 2. Instructor: Neal Snape ([email protected]) 2 The sounds of language: Consonants PHONETICS: The science of human speech sounds; describing sounds by grouping sounds into classes - similarities distinguishing sounds - differences SOUNDS: CONSONANTS & VOWELS (GLIDES) - defined by the constriction of the air channel CONSONANTS: Sounds made by constricting the airflow from the lungs. - defined by: the PLACE of articulation (where is the sound made?) and the MANNER of articulation (How is the sound made?) PLACE: Bilabial: [p, b, m] both lips Labio-dental: [f, v] lip & teeth Dental: [†, ∂] tongue tip & teeth Alveolar: [t, d, s, z, l, r, n] tongue tip & AR* Palato-alveolar: [ß, Ω, ß, Ω] tongue blade & AR/ hard palate Palatal: [j] tongue (front) & hard palate Velar: [k, g, Ñ] tongue (back) & velum Labio-velar: [w] lips & tongue (back) & velum Glottal: [h, ÷] vocal cords (glottis) * AR = alveolar ridge MANNER: Plosives: [p, b, t, d, k, g, ÷] closure Fricatives: [f, v, †, ∂, s, z, ß, Ω, h] friction Affricates: [ß,Ω] combination Nasals: [m, n, Ñ] nasal cavity Liquid: [l, r] partly blocked Glides: [w, j] vowel-like 1 Manner of articulation is about how the sound is produced. It is divided into two types: obstruents (obstruction the air-stream causing the heightened air- pressure) and sonorants (no increase of the air-pressure). Then, each of them is further divided into as follows: Manners of articulation Obstruents Sonorants Stops Fricatives Affricates Nasals Approximants (closure → release) (friction) (closure → friction) (through nose) (partial block + free air-stream) Liquids Glides Rhotics Laterals (through center (through sides of tongue) of tongue) Figure 1. -

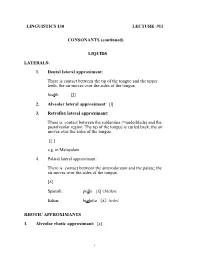

1. Dental Lateral Approximant: There Is Contact Between the Tip of the Tongue and the Upper Teeth; the Air Moves Over the Sides of the Tongue

LINGUISTICS 130 LECTURE #11 CONSONANTS (continued) LIQUIDS LATERALS: 1. Dental lateral approximant: There is contact between the tip of the tongue and the upper teeth; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. health [l∞] 2. Alveolar lateral approximant: [l] 3. Retroflex lateral approximant: There is contact between the sublamina (=underblade) and the postalveolar region. The tip of the tongue is curled back; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Æ ] e.g. in Malayalam 4. Palatal lateral approximant: There is contact between the anterodorsum and the palate; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Ò] Spanish: pollo [Ò] chicken Italian: bigletto [Ò] ticket RHOTIC APPROXIMANTS 1. Alveolar rhotic approximant: [®] 1 2. Retroflex rhotic approximant: The sublamina approximates the postalveolar region while the tip of the tongue is curled back. [ï] FLAPS The active articulator (tip of the tongue) strikes the place of articulation, and after momentary contact it immediately withdraws. MOMENTARY CONTACT BETWEEN TWO ARTICULATORS! Alveolar flaps: the tip of the tongue makes momentary contact with the alveolar ridge. Common in North American English: [‰] alveolar flap (voiced) Betty, writer, rider [‰] TRILLS One articulator is held loosely near to another so that the flow of air between them sets one of the articulators (e.g. the tongue) in motion, alternately sucking them together and blowing them apart. There are usually three vibrating movements in a typical trill. 1. Alveolar trill: apex articulators alveolar ridge [r] (voiced) Finnish: raha [r] money 2 2. Uvular trill: dorsum articulators uvula [R] (voiced) It occurs in some varieties of French instead of the uvular fricative. -

LIN 3201 Sounds of Human Language Manual by Ratree

LIN 3201 Sounds of Human Language Manual By Ratree Wayland Program in Linguistics University of Florida Gainesville, FL 2 Introduction There are approximately 7,000 languages in the world, and the sounds employed by these languages show both similarities and differences. Thus, an interesting question that one might ask is, “What factors affect the sounds a language can or cannot use?” First of all, we are constrained by what we can do with our tongue, our lips and other organs involved in the production of speech sounds. This factor may be referred to as the ‘articulatory ease’ factor. Secondly, we are constrained by what we can hear or what we can perceptually distinguish. This is the ‘auditory distinctiveness’ factor. Thus, no language in the world has sounds that are too difficult for native speakers to produce or to perceptually differentiate. To nonnative speakers, however, certain sounds may prove challenging to both produce and perceive. One of the goals of this course is to familiarize students with the various sounds employed in the world’s languages. Students will learn how to describe, produce and perceptually distinguish these sounds. Describing Speech Sounds Phonetics is concerned with describing speech sounds that occur in the world’s languages. Speech sounds can be described in at least two different ways. First we can describe them in terms of how they are made in the vocal tract (articulatory phonetics). As speech sounds leave the mouth, they cause disturbances in the surrounding air (sound waves). Thus, another way that we can describe speech sound is to analyze its acoustic sound wave (acoustic 3 phonetics).