Downloaded 2021-10-03T14:42:08Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Annual Report 2015

TITHE AN OIREACHTAIS AN COMHCHOISTE UM FHORFHEIDHMIÚ CHOMHAONTÚ AOINE AN CHÉASTA TUARASCÁIL BHLIANTÚIL 2015 _______________ HOUSES OF THE OIREACHTAS JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2015 PR Number: Committee unique identifier no. Table of Contents 1 Content and Format of Report 2. Establishment and Functions 3. Meetings, Attendance and Recording 4. Number and Duration of Meetings 5. Witnesses attending before the Committee 6. Committee Reports Published 7. Travel 8. Report on Functions and Powers APPENDIX 1 Orders of Reference APPENDIX 2: List of Members APPENDIX 3: Meetings of the Joint Committee APPENDIX 4: Minutes of Proceedings of the Joint Committee 1. Content and Format of Report This report has been prepared pursuant to Standing Order 86 (3), (4), (5) and (6) (Dáil Éireann) and Standing Order 75 (3), (4), (5) and (6) (Seanad Éireann) which provide for the Joint Committee to- undertake a review of its procedure and its role generally; prepare an annual work programme; lay minutes of its proceedings before both Houses; make an annual report to both Houses. At its meeting on the 21 January 2016, the Joint Committee agreed that all these items should be included in this report covering the period from 1st January 2015 to 31st December 2015. 2. Establishment of Joint Committee. The Dáil Select Committee, established by Order of Dáil Éireann on the 8 June 2011 was enjoined with a Select Committee of Seanad Éireann, established by Order of Seanad Éireann on the 16 June 2011, to form the Joint Committee on the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement. -

Brief Amicus Curiae of the Senate of the United Mexican States, Et

No. 08-987 IN THE RUBEN CAMPA, RENE GONZALEZ, ANTONIO GUERRERO, GERARDO HERNANDEZ, AND LUIS MEDINA, Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ON BEHALF OF THE SENATE OF THE UNITED MEXICAN STATES, THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PANAMA, MARY ROBINSON (UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, 1997- 2002; PRESIDENT OF IRELAND, 1992-1997) AND LEGISLATORS FROM THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNTRIES OF BRAZIL, BELGIUM, CHILE, GERMANY, IRELAND, JAPAN, MEXICO, SCOTLAND AND THE UNITED KINGDOM ______________ Michael Avery Counsel of Record Suffolk Law School 120 Tremont Street Boston, MA 02108 617-573-8551 ii AMICI CURIAE The Senate of the United Mexican States The National Assembly of Panama Mary Robinson (United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1997-2002; President of Ireland, 1992-1997) Legislators from the European Parliament Josep Borrell Fontelles, former President Enrique Barón Crespo, former President Miguel Ángel Martínez, Vice-President Rodi Kratsa-Tsagaropoulou, Vice-President Luisa Morgantini, Vice-President Mia De Vits, Quaestor Jo Leinen, Chair of the Committee on Constitutional Affairs Richard Howitt, Vice-Chair of the Subcommittee on Human Rights Guisto Catania, Vice-Chair of the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Willy Meyer Pleite, Vice-Chair of the Delegation to the Euro-Latin American Parliamentary Assembly Edite Estrela, Vice-Chair -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

Guide to the 30 Dáil for Anti-Poverty Groups

European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN) Ireland Guide to the 30th Dáil for Anti-Poverty Groups ‘EAPN Ireland is a network of groups and individuals working against poverty and social exclusion. Our objective is to put the fight against poverty at the top of the European and Irish agendas’ Contents Page Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 2 The Parties 4 Dáil Session Guide 5 A Brief Guide to Legislation 7 Dáil Committees 9 The TD in the Dáil 9 Contacting a TD 12 APPENDICES 1: List of Committees and Spokespersons 2: Government Ministers and Party Spokespersons 1 Introduction This Guide has been produced by the European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN) Ireland. It is intended as a short briefing on the functioning of the Dáil and a simple explanation of specific areas that may be of interest to people operating in the community/NGO sector in attempting to make the best use of the Dáil. This briefing document is produced as a result of the EAPN Focus on Poverty in Ireland project, which started in December 2006. This project aimed to raise awareness of poverty and put poverty reduction at the top of the political agenda, while also promoting understanding and involvement in the social inclusion process among people experiencing poverty. This Guide is intended as an accompanying document to the EAPN Guide to Understanding and Engaging with the European Union. The overall aim in producing these two guides is to inform people working in the community and voluntary sector of how to engage with the Irish Parliament and the European Union in influencing policy and voicing their concerns about poverty and social inclusion issues. -

18 Seanad E´ Ireann 291

18 SEANAD E´ IREANN 291 De´ Ce´adaoin, 21 Ma´rta, 2007 Wednesday, 21st March, 2007 10.30 a.m. RIAR NA hOIBRE Order Paper GNO´ POIBLI´ Public Business 1. Tuarasca´il o´ n gCoiste um No´ s Imeachta agus Pribhle´idı´. Report of the Committee on Procedure and Privileges. 2. An Bille um Rialu´ Foirgnı´ochta 2005 [Da´il] — An Coiste. Building Control Bill 2005 [Da´il] — Committee. 3. (l) An Bille um Chlu´ mhilleadh 2006 — An Coiste (leasu´ 23 ato´ga´il). (a) Defamation Bill 2006 — Committee (amendment 23 resumed). Tı´olactha: Presented: 4. An Bille um Chaomhnu´ Fostaı´ochta (Comhiomarcaı´ochtaı´ Eisceachtu´ la agus Nithe Gaolmhara) 2007 — Ordu´ don Dara Ce´im. Protection of Employment (Exceptional Collective Redundancies and Related Matters) Bill 2007 — Order for Second Stage. Bille da´ ngairtear Acht do dhe´anamh Bill entitled an Act to make provision, socru´ , de dhroim an creatchomhaontu´ consequent on the conclusion of the ten- comhpha´irtı´ochta so´ isialaı´ deich mbliana year framework social partnership 2006-2015 ar a dtugtar ‘‘I dTreo 2016’’ a agreement 2006-2015 known as ‘‘Towards chrı´ochnu´ , maidir le paine´al iomarcaı´ochta 2016’’, for the establishment of a a bhunu´ agus comhiomarcaı´ochtaı´ redundancy panel and the reference to it of beartaithe a´irithe a tharchur chuige agus certain proposed collective redundancies maidir le gnı´omhaı´ocht ghaolmhar ag an and for related action by the Minister for Aire Fiontar, Tra´da´la agus Fostaı´ochta, Enterprise, Trade and Employment, lena n-a´irı´tear tuairimı´ a fha´il o´ n gCu´ irt including -

The State, Public Policy and Gender: Ireland in Transition, 1957-1977

The State, Public Policy and Gender: Ireland in Transition, 1957-1977 Eileen Connolly MA Dissertation submitted for the degree of PhD under the supervision of Professor Eunan O’Halpin at Dublin City University Business School September 1998 I hereby certify that this material, which 1 submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save as and to the extent that, such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed Eileen Connolly CONTENTS Page Declaration ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter One: Gender and the State 8 Chapter Two: Consensus in the 1950s 38 Chapter Three: Breaking the Consensus 68 Chapter Four: Negotiating Policy Change, 1965 -1972 92 Chapter Five: The Equality Contract 143 Chapter Six: The Political Parties and Women’s Rights 182 Chapter Seven: European Perspectives 217 Chapter Eight: Conclusion 254 Bibliography 262 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Eunan O’Halpin for his support and guidance during the writing of this dissertation. I am grateful to DCUBS for the research studentship which enabled me to cany out this research. I would also like to thank the staff of the National Library of Ireland, the National Archives, the libraries of Dublin City University and University College Dublin, the National Women’s Council of Ireland and the Employment Equality Agency for their help in the course of my research. I am grateful to a number of people in DCUBS for commenting on and reading earlier drafts, particularly Dr Siobhain McGovern, Dr David Jacobson and Dr Pat Barker. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 746 Tuesday, No. 3 15 November 2011 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Dé Máirt, 15 Samhain 2011. Business of Dáil ……………………………… 417 Ceisteanna — Questions Minister for Finance Priority Questions …………………………… 417 Other Questions …………………………… 428 Leaders’ Questions ……………………………… 437 Visit of Scottish Delegation …………………………… 445 Ceisteanna — Questions (resumed) Taoiseach ………………………………… 446 Termination of Ministerial Appointment: Announcement by Taoiseach …………… 464 Order of Business ……………………………… 464 Suspension of Member……………………………… 472 Topical Issue Matters ……………………………… 474 Topical Issue Debate Sale of Booterstown Marsh ………………………… 475 Banking Sector Regulation ………………………… 477 Northern Ireland Issues …………………………… 480 Stroke Services ……………………………… 482 Order of Referral of the Access to Central Treasury Funds (Commission for Energy Regulation) Bill 2011 [Seanad] to the Select Sub-Committee on Communications, Energy and Natural Resources: Motion to Rescind ………………………… 484 Dormant Accounts (Amendment) Bill 2011 [Seanad]: Second Stage …………… 485 Message from Select Committee ………………………… 497 Private Members’ Business Mental Health Services: Motion ………………………… 498 Questions: Written Answers …………………………… 519 DÁIL ÉIREANN ———— Dé Máirt, 15 Samhain 2011. Tuesday, 15 November 2011. ———— Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 2.00 p.m. ———— Paidir. Prayer. ———— Business of Dáil An Ceann Comhairle: I am pleased to inform Members that as of 2 p.m. today, the pro- ceedings of the House will be broadcast live on channel 801 on the UPC network, as part of a trial initiative for a period of six months. This trial is being provided at no cost to the Exchequer. As Ceann Comhairle, I am particularly pleased that the notion of increased access to the work of Parliament and its Members is being enhanced with the launch of this initiative. -

Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish Elections Under a Different Electoral System

Publicpolicy.ie Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish elections under a different electoral system. A Submission to the Convention on the Constitution. Dr Adrian Kavanagh & Noel Whelan 1 Forward Publicpolicy.ie is an independent body that seeks to make it as easy as possible for interested citizens to understand the choices involved in addressing public policy issues and their implications. Our purpose is to carry out independent research to inform public policy choices, to communicate the results of that research effectively and to stimulate constructive discussion among policy makers, civil society and the general public. In that context we asked Dr Adrian Kavanagh and Noel Whelan to undertake this study of the possible outcomes of the 2007 and 2011 Irish Dail elections if those elections had been run under a different electoral system. We are conscious that this study is being published at a time of much media and academic comment about the need for political reform in Ireland and in particular for reform of the electoral system. While this debate is not new, it has developed a greater intensity in the recent years of political and economic volatility and in a context where many assess the weaknesses in our political system and our electoral system in particular as having contributed to our current crisis. Our wish is that this study will bring an important additional dimension to discussion of our electoral system and of potential alternatives. We hope it will enable members of the Convention on the Constitution and those participating in the wider debate to have a clearer picture of the potential impact which various systems might have on the shape of the Irish party system, the proportionality of representation, the stability of governments and the scale of swings between elections. -

Summary of the 44Th Plenary Session, May 2012

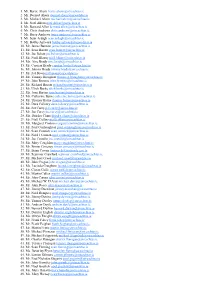

British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly Tionól Parlaiminteach na Breataine agus na hÉireann Forty-Fourth Plenary Session 13 - 15 May 2012, Dublin MEMBERSHIP OF THE BRITISH-IRISH PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY Steering Committee Co-Chairmen Mr Laurence ROBERTSON MP Mr Joe McHUGH TD Vice-Chairmen Rt Hon Paul MURPHY MP Mr Séamus KIRK TD Mr Robert WALTER MP Mr Pádraig MacLOCHLAINN TD Devolved Assemblies and Crown Dependencies Dr Alasdair McDONNELL MLA/Mr John McCALLISTER MLA Mr John SCOTT MSP, Mr David MELDING AM, Mr Steven Rodan SHK Members in Attendance Oireachtas Members British Members Mr Joe McHUGH TD, Co-Chair Mr Laurence ROBERTSON MP Senator Paschal MOONEY Rt Hon Paul MURPHY MP Mr Mattie McGRATH TD Mr Robert WALTER MP Mr Séamus KIRK TD Baroness SMITH of BASILDON (Assoc) Mr Pádraig MacLOCHLAINN TD Lord BEW Mr Luke Ming FLANAGAN TD Baroness BLOOD MBE Senator Jim WALSH Viscount BRIDGEMAN Mr Arthur SPRING TD Lord GORDON of STRATHBLANE (Assoc) Mr Jack WALL TD Mr Conor BURNS MP Ms Ann PHELAN TD Mr Paul FARRELLY MP (Associate) Ms Ciara CONWAY TD Mr Jim DOBBIN MP Mr Martin HEYDON TD Lord DUBS Mr Patrick O'DONOVAN TD Mr Paul FLYNN MP Mr Noel COONAN TD Mr Stephen LLOYD MP Mr Joe O'REILLY TD Baroness HARRIS of RICHMOND Senator Terry BRENNAN (Assoc) Mr Kris HOPKINS MP Senator Paul COGHLAN Rt Hon Lord MAWHINNEY Mr Frank FEIGHAN TD Mr John ROBERTSON MP Mr Séan CONLAN TD Lord ROGAN Senator Imelda HENRY Mr Chris RUANE MP Mr John Paul PHELAN TD Mr Jim SHERIDAN MP Senator Cáit KEANE Lord GERMAN (Assoc) Senator John CROWN Mr Gavin WILLIAMSON MP Senator Jimmy HARTE -

Seanad General Election July 2002 and Bye-Election to 1997-2002

SEANAD E´ IREANN OLLTOGHCHA´ N DON SEANAD, IU´ IL 2002 agus Corrthoghcha´in do Sheanad 1997-2002 SEANAD GENERAL ELECTION, JULY 2002 and Bye-Elections to 1997-2002 Seanad Government of Ireland 2003 CLA´ R CONTENTS Page Seanad General Election — Explanatory Notes ………………… 4 Seanad General Election, 2002 Statistical Summary— Panel Elections …………………………… 8 University Constituencies ………………………… 8 Panel Elections Cultural and Educational Panel ……………………… 9 Agricultural Panel …………………………… 13 Labour Panel ……………………………… 19 Industrial and Commercial Panel ……………………… 24 Administrative Panel …………………………… 31 University Constituencies National University of Ireland………………………… 35 University of Dublin …………………………… 37 Statistical Data — Distribution of Seats between the Sub-Panels 1973-02 … … … 38 Members nominated by the Taoiseach …………………… 39 Alphabetical list of Members ………………………… 40 Photographs Photographs of candidates elected ……………………… 42 Register of Nominating Bodies, 2002 ……………………… 46 Panels of Candidates …………………………… 50 Rules for the Counting of Votes Panel Elections ……………………………… 64 University Constituencies ………………………… 68 Bye-Elections ……………………………… 71 23 June, 1998 ……………………………… 72 2 June, 2000 ……………………………… 72 2 June, 2002 ……………………………… 73 18 December, 2001 …………………………… 73 3 SEANAD GENERAL ELECTION—EXPLANATORY NOTES A. CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS ARTICLE 18 ‘‘4. The elected members of Seanad E´ ireann shall be elected as follows:— i. Three shall be elected by the National University of Ireland. ii. Three shall be elected by the University of Dublin. iii. Forty-three shall be elected from panels of candidates constituted as hereinafter provided. 5. Every election of the elected members of Seanad E´ ireann shall be held on the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote, and by secret postal ballot. 6. The members of Seanad E´ ireann to be elected by the Universities shall be elected on a franchise and in the manner to be provided by law. -

Oireachtas Monitor 193 Published: 30 November 2015

Oireachtas Monitor 193 Published: 30 November 2015 1. Coming up this week in the Houses of the Oireachtas (30 November 2015 - 4 December 2015) Dail and Seanad Agenda 2. Last week's Oireachtas Questions and Debates (23 November 2015 - 27 November 2015) a. Asylum/Immigration b. Education (incl. ECCE and Child Care) c. Child Services/Children in Care d. Child Abuse/Child Protection e. Family f. Disability and Special Educational Needs g. Health and Wellbeing h. Child Benefit/Social Welfare/Poverty/Housing i. Juvenile Justice/Human Rights/ Equality a. Asylum/ Immigration Parliamentary Questions- Written Answers Department of Justice and Equality: Refugee Status Applications, Clare Daly (Dublin North, United Left) b.Education (incl. ECCE and Child Care) Parliamentary Questions- Written Answers Department of Children and Youth Affairs: Child Care Programmes, Joanna Tuffy (Dublin Mid West, Labour) Child Care Services Regulation, Seán Fleming (Laois-Offaly, Fianna Fail) Preschool Services, Michael Healy-Rae (Kerry South, Independent) Early Childhood Care Education, Pat Rabbitte (Minister, Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources; Dublin South West, Labour) Early Childhood Care Education, Éamon Ó Cuív (Galway West, Fianna Fail) Early Childhood Care Education, Peadar Tóibín (Meath West, Sinn Fein) Department of Education and Skills: School Curriculum, Tom Fleming (Kerry South, Independent) Skills Shortages, Tom Fleming (Kerry South, Independent) Teaching Contracts, Fergus O'Dowd (Louth, Fine Gael) School Funding, Seán -

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4. Mr. Noel Ahern [email protected] 5. Mr. Bernard Allen [email protected] 6. Mr. Chris Andrews [email protected] 7. Mr. Barry Andrews [email protected] 8. Mr. Seán Ardagh [email protected] 9. Mr. Bobby Aylward [email protected] 10. Mr. James Bannon [email protected] 11. Mr. Sean Barrett [email protected] 12. Mr. Joe Behan [email protected] 13. Mr. Niall Blaney [email protected] 14. Ms. Aíne Brady [email protected] 15. Mr. Cyprian Brady [email protected] 16. Mr. Johnny Brady [email protected] 17. Mr. Pat Breen [email protected] 18. Mr. Tommy Broughan [email protected] 19. Mr. John Browne [email protected] 20. Mr. Richard Bruton [email protected] 21. Mr. Ulick Burke [email protected] 22. Ms. Joan Burton [email protected] 23. Ms. Catherine Byrne [email protected] 24. Mr. Thomas Byrne [email protected] 25. Mr. Dara Calleary [email protected] 26. Mr. Pat Carey [email protected] 27. Mr. Joe Carey [email protected] 28. Ms. Deirdre Clune [email protected] 29. Mr. Niall Collins [email protected] 30. Ms. Margaret Conlon [email protected] 31. Mr. Paul Connaughton [email protected] 32. Mr. Sean Connick [email protected] 33. Mr. Noel J Coonan [email protected] 34.