Implementing Sanitation for Informal Settlements: Conflicting Rationalities in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Covering in the Online Press Media During the ANC Elective Conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107

News covering in the online press media during the ANC elective conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at Centre for Communication, Media and Society in the School of Applied Human Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Supervisor: Professor Donal McCracken 2019 As the candidate's supervisor, I agree with the submission of this thesis. …………………………………………… Professor Donal McCracken i Declaration - plagiarism I, ……………………………………….………………………., declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons' data, pictures, graphs or other information unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written, but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and the References sections. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… ii Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to the discipline of CCMS at Howard College, UKZN, led by Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli. It was the discipline’s commitment to academic research and academic excellence that attracted me to pursue this degree at CCMS (a choice that I don’t regret). -

Examination of the Capacity of Limpopo Water Services Authorities in Providing Access to Clean Drinking Water and Decent Sanitation

EXAMINATION OF THE CAPACITY OF LIMPOPO WATER SERVICES AUTHORITIES IN PROVIDING ACCESS TO CLEAN DRINKING WATER AND DECENT SANITATION By KGOSHI KGASHANE LUCAS PILUSA (STUDENT No. 201406085) SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION In the FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT AND COMMERCE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION At the UNIVERSITY OF FORT HARE SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR M.H. KANYANE COMPLETED 16 APRIL 2018 DECLARATION I, Kgoshi Kgashane Lucas Pilusa, Student Number 201406085, hereby declare that the thesis titled “Examination of the capacity of Limpopo Water Services Authorities in providing access to clean drinking water and decent sanitation”, submitted to the University of Fort Hare for the degree DPhil in Public Administration, has not previously been submitted to any other university or institution. It is my own work in design and execution. Furthermore, the references used or quoted herein have been duly acknowledged. _______________ K.K.L. PILUSA DATE 23 April 2019 i DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my late Father and brother, Masilo William Pilusa and Thabo Eric Pilusa, who have passed on and cannot share the joy of my accomplishment. Their love was amazing, magnificent and inspirational. I am still feeling the vacuum of their departure. May their loving souls rest in eternal amity. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would have been a futile exercise were it not for the guidance and aid of the Lord God Almighty, the creator of Heaven and Earth and the one and only Shepherd of humankind. I am indebted to many people for their contribution towards the execution of this study, many of whom are not mentioned by name due to the constraints of space. -

State Capture and the Political Manipulation of Criminal Justice Agencies a Joint Submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into Allegations of State Capture

State capture and the political manipulation of criminal justice agencies A joint submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture CORRUPTION WATCH AND THE INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY STUDIES APRIL 2019 State capture and the political manipulation of criminal justice agencies A joint submission by Corruption Watch and the Institute for Security Studies to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture April 2019 Contents Executive summary ..........................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 Structure and purpose of this submission .....................................................................................................3 Impact of manipulation of criminal justice agencies .......................................................................................4 Recent positive developments .......................................................................................................................4 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................4 Fixing the legacy of the manipulation of criminal justice agencies..............................................................4 Addressing risk factors for future manipulation -

ANC Heavyweights Placed at Heart of Bosasa Operation

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Wednesday 29 September 2021 ANC heavyweights placed at heart of Bosasa operation ANC heavyweights and state officials have been placed at the heart of Bosasa’s operation to safeguard itself from any investigation of its corrupt multi-billion rand contracts with government in the latest round of allegations placed before the Zondo Commission of Inquiry, notes Legalbrief. On a fourth day of testimony, former Bosasa executive Angelo Agrizzi laid bare how the controversial facilities company lined the pockets of Ministers, former and current ANC MPs, and officials working in various departments. The corruption also went to the core of Parliament, according to Agrizzi, who alleged long-standing ANC MP Vincent Smith, and other MPs, were paid up to R100 000 a month to protect Bosasa. Heading the list of ANC heavyweights that Bosasa, now trading as African Global Operations, had on its payroll was Environmental Affairs Minister Nomvula Mokonyane. According to a Business Day report, the Minister insisted that the firm foot the bill for ANC rallies, birthday celebrations, funeral services and even a rental car for her daughter. Agrizzi said that Bosasa had paid for at least a dozen ANC events, including the party’s Siyanqoba rallies, which are held before elections. Apart from favours for the party, Agrizzi also described how he had been given a list of Christmas groceries to buy for Mokonyane every year since 2002. The company also paid for repairs to her Roodepoort home. Mokonyane has denied the allegations. Mokonyane allegedly received cash bribes of R50 000 over the course of several years – at times delivered to her at her official residence as the Premier of Gauteng, says a Daily Maverick report. -

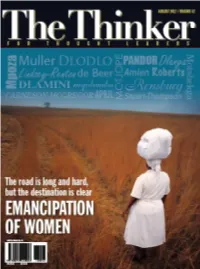

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

Media Release 7 September 2015 the World Gathers For

MEDIA RELEASE 7 SEPTEMBER 2015 THE WORLD GATHERS FOR THE XIV WORLD FORESTRY CONGRESS Durban - The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Mr Senzeni Zokwana officially opened the XIV World Forestry Congress today. Also present to officiate the ceremony was Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, FAO Special Ambassador for Forests and the Environment HRH Prince Laurent of Belgium, African Union Commission chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Minister of Water and Sanitation Nomvula Mokonyane, Deputy Minister Bheki Cele including the provincial leadership of agriculture. The congress, hosted for the first time on African soil, will run from 7-11 September 2015 under the theme ‘’Forests and People: Investing in a Sustainable Future.’’. The congress aims to focus on global issues affecting the forestry sector and provide a platform for sharing of knowledge and experience regarding the conservation, management and use of the world's forests. Speaking at the opening ceremony Minister Zokwana said, “Forests not only deliver timber and timber products, but also non-wood forest products which improve the social-economic standing in our communities - trees and forests also contribute towards food security.” The highlight of the day was the planting of the millionth tree under the department’s Million Trees Programme. The Million Trees Programme was launched during the 2007 Arbor Week campaign as part of the South African contribution to the United Nations Environment Programme “Plant for the Planet: Billion Tree Campaign”, where communities, industry, civil society organisations and governments are encouraged to plant at least one billion trees worldwide. Join the engagement by using the hashtag #Forests2015. For further information please contact Makenosi Maroo on 072 475 2956 or Bomikazi Molapo on 078 801 3711 . -

Pocket Guide to South Africa 2010/2011: Government

GOVERNMENT 19 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2010/11 GOVERNMENT Government’s outcomes approach is embedded in and a direct resultant of the electoral mandate. Five priority areas were identified: decent work and sus- tainable livelihoods, education, health, rural development, food security and land reform and the fight against crime and corruption. These translated into 12 outcomes to create a better life for all: • an improved quality of basic education • a long and healthy life for all South Africans • all South Africans should be safe and feel safe • decent employment through inclusive growth • a skilled and capable workforce to support an inclusive growth path • an efficient, competitive and responsive economic infra- structure network • vibrant, equitable, sustainable rural communities with food security for all • sustainable human settlements and an improved quality of household life • a responsive, accountable, effective and efficient local government system • environmental assets and natural resources that are well protected and enhanced • a better Africa and a better world as a result of South Africa’s contributions to global relations • an efficient and development-oriented public service and an empowered, fair and inclusive citizenship. In 2010, performance agreements for the outcomes were signed between President Jacob Zuma and Cabinet ministers. Delivery agreements will further unpack each outcome. The Department for Performance Monitoring and Evaluation in The Presidency will facilitate the process of regular reporting and monitoring of progress against the agreed outputs and targets in the delivery agreements. This process will foster an understanding of how the various spheres of government are working together to achieve the outcomes. The Presidency, March 2011 President: Jacob Zuma Deputy President: Kgalema Motlanthe 20 The Constitution The Constitution is the supreme law of the country. -

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa PO Box 740 Auckland park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 011 381 6000 Fax: +27 011 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 978-1-920446-45-1 © EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2014 EISA acknowledges the contributions made by the EISA staff, the regional researchers who provided invaluable material used to compile the Updates, the South African newspapers and the Update readers for their support and interest. Printing: Corpnet, Johannesburg CONTENTS PREFACE 7 ____________________________________________________________________ ELECTIONS IN 2014 – A BAROMETER OF SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS AND 9 SOCIETY? Professor Dirk Kotze ____________________________________________________________________ 1. PROCESSES ISSUE 19 Ebrahim Fakir and Waseem Holland LEGAL FRAMEWORK 19 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN ELECTORAL LAW 21 ELECTION TIMETABLE 24 ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 25 NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS OF ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 26 ELECTORAL SYSTEM 27 VOTING PROCESS 28 WORKINGS OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM 29 COUNTING PROCESS 30 2014 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS – VOTER REGISTRATION 32 STATISTICS AND PARTY REGISTRATION ____________________________________________________________________ 2. SA ELECTIONS 2014: CONTINUITY, CONTESTATION OR CHANGE? 37 THE PATH OF THE PAST: SOUTH AFRICAN DEMOCRACY TWENTY YEARS ON 37 Professor Steven Friedman KWAZULU-NATAL 44 NORTH WEST 48 LIMPOPO 55 FREE STATE 59 WESTERN CAPE 64 MPUMALANGA 74 GAUTENG 77 ____________________________________________________________________ 3 3. -

Ruling Party in Disarray Over Covid-19 Corruption

ACTIONABLE AFRICAN BUSINESS RISK INTELLIGENCE SOUTH AFRICA: 01 September 2020 RULING PARTY IN DISARRAY OVER COVID-19 CORRUPTION A stream of allegations of COVID-19-related corruption has shocked the ruling party and undermined confidence in the government of President Cyril Ramaphosa. The president now faces a challenge from within his own party to remove him early next year and a cabinet reshuffle is imminent. In the meantime, political manoeuvring and graft probes will distract from the coronavirus response, reform of state-owned enterprises, and negotiations with the IMF to avoid a sovereign debt crisis. On 28 August, South Africa?s former president Jacob Zuma accused current President Cyril Ramaphosa of bringing into disrepute the governing African National Congress (ANC) party with his stance against corruption. Zuma?s statement, which is the first time he has publicly rebuked his successor in over two years, came in response to Ramaphosa?s letter to ANC members blaming its leaders for extensive corruption and fraud in the procurement of coronavirus personal protective equipment (PPE). In his letter, Ramaphosa told the party that it stands as ?accused number one.? While the president has survived a recent challenge to his leadership, rival factions in the party are moving to seek his removal from office early next year. EXX AFRICA - SOUTH AFRICA: RULING PARTY IN DISARRAY OVER COVID-19 CORRUPTION Meanwhile, following a conference of the ANC?s top decision-making body on 29 and 30 August, Ramaphosa has been referred to the party?s integrity commission to probe allegations of misleading the country?s parliament about campaign donations he received while running for the ANC leadership in 2017. -

Zuma's Agenda-Driven Cabinet Reshuffles

19 February 2019 Zondo Commission – Zuma’s agenda-driven cabinet reshuffles created havoc in financial markets It takes a person with no appreciation for the impact that government’s social spending programmes have on the ordinary citizen to make a comment like “if the rand falls, we will just pick it up.” This is the view of National Treasury’s chief director of macro-economic policy, Catherine MacLeod, who testified at the commission of inquiry into state capture on Tuesday. MacLeod was responding to a question by evidence leader Phillip Mokoena SC, who asked for her comment on the remark, attributed to environmental affairs minister Nomvula Mokonyane. The minister uttered the words at an ANC rally in April 2017, in defence of a surprise cabinet reshuffle by former president Jacob Zuma the month before. Two casualties of the reshuffle were finance minister Pravin Gordhan and his deputy Mcebisi Jonas, based on an intelligence report that found that they were undermining the leadership of the country in the way they ran Treasury. The pair, together with then director-general Lungisa Fuzile, had set out on a tour of several countries to meet with potential investors and rating agencies, a task they would commonly embark on once or twice a year, according to Fuzile. “Financial asset prices may recover eventually,” MacLeod explained, “but the thing is, between the time that they have fallen and when they finally recover, government has to go out into the market and convince people to lend us money, and during that period of time we have to pay more in order to convince them to lend money to us.” This is so that we can continue to fund our social spending programmes, she said. -

South Africa's 20-Year Journey in Water and Sanitation Research

South Africa’s 20-year journey in water and sanitation research South Africa’s 20-year journey in water and sanitation research Contents Minister’s Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 WRC CEO’s Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Informing policy and decision making ............................................................................................................................... 19 The water research journey of transformation ............................................................................................................ 49 Transforming South African society ..................................................................................................................................... 67 Empowering communities .......................................................................................................................................................... 85 New products and services for economic development ................................................................................105 Sustainable development -

Hier Steht Später Die Headline

S SOUTH AFRICA:COUNTRY PROFILE Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation February 2014 ww.kas.de/Südafrika Contents 1. General Information: Republic of South Africa ......................................................................................... 2 2. Most important events in the South African history .................................................................................. 3 3. The political System of South Africa ....................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Executive power .............................................................................................................................. 4 3.2 Legislative power ............................................................................................................................. 5 3.3 Judicial Power ................................................................................................................................. 9 4. Economy .......................................................................................................................................... 10 5. Society and development status .......................................................................................................... 13 6. List of references ............................................................................................................................... 17 1. General Information: Republic of South Africa1 State and Politics Form of government (Federal) republic Governance Parliamentary democracy