Maayan Sheleff and Sarah Spies (Eds.) (Un)Commoning Voices and (Non)Communal Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEFINING FORM / a GROUP SHOW of SCULPTURE Curated by Indira Cesarine

DEFINING FORM / A GROUP SHOW OF SCULPTURE Curated by Indira Cesarine EXHIBITING ARTISTS Alexandra Rubinstein, Andres Bardales, Ann Lewis, Arlene Rush, Barb Smith, Christina Massey, Colin Radcliffe, Daria Zhest, Desire Rebecca Moheb Zandi, Dévi Loftus, Elektra KB, Elizabeth Riley, Emily Elliott, Gracelee Lawrence, Hazy Mae, Indira Cesarine, Jackie Branson, Jamia Weir, Jasmine Murrell, Jen Dwyer, Jennifer Garcia, Jess De Wahls, Jocelyn Braxton Armstrong, Jonathan Rosen, Kuo-Chen (Kacy) Jung, Kate Hush, Kelsey Bennett, Laura Murray, Leah Gonzales, Lola Ogbara, Maia Radanovic, Manju Shandler, Marina Kuchinski, Meegan Barnes, Michael Wolf, Nicole Nadeau, Olga Rudenko, Rachel Marks, Rebecca Goyette, Ron Geibel, Ronald Gonzalez, Roxi Marsen, Sandra Erbacher, Sarah Hall, Sarah Maple, Seunghwui Koo, Shamona Stokes, Sophia Wallace, Stephanie Hanes, Storm Ascher, Suzanne Wright, Tatyana Murray, Touba Alipour, We-Are-Familia x Baang, Whitney Vangrin, Zac Hacmon STATEMENT FROM CURATOR, INDIRA CESARINE “What is sculpture today? I invited artists of all genders and generations to present their most innovative 2 and 3-dimensional sculptures for consideration for DEFINING FORM. After reviewing more than 600 artworks, I selected sculptures by over 50 artists that reflect new tendencies in the art form. DEFINING FORM artists defy stereotypes with inventive works that tackle contemporary culture. Traditionally highly male dominated, I was inspired by the new wave of female sculptors making their mark with works engaging feminist narratives. The artworks in DEFINING FORM explode with new ideas, vibrant colors, and display a thoroughly modern sensibility through fearless explorations of the artists and unique usage of innovative materials ranging from fabric, plastic, and foam to re-purposed and found objects including chewing gum, trash and dirt. -

Bangor University to Cut £5M

Bangor Remembrance 2018 100 Years On - Bangor Remembers The Fallen FREE Page AU Match 9 Reports Inside AU Focus Fixture: Ultimate Frisbee Page 53 November Issue 2018 Issue No. 273 seren.bangor.ac.uk @SerenBangor Y Bangor University Students’ Union English Language Newspaper Bangor University To Cut £5m VICE-CHANCELLOR EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW “Protect the student experience at all costs,” says Vice-Chancellor John G. Hughes FULL by FINNIAN SHARDLOW also mentioned as a reason for these However, Hughes says further cuts unions. Plaid Cymru’s Sian Gwenllian cuts. will need to be made to secure Bangor’s AM expressed “huge concern,” INTERVIEW angor University are aiming to 50 jobs are at risk as compulsory long-term future. maintaining that the university must make savings of £5m. redundancies are not ruled out. “What we’re doing is taking prudent avoid compulsory redundancies. Sta received a letter from Vice- In the letter, seen by Newyddion steps to make sure we don’t get into a In an exclusive interview with Seren, INSIDE BChancellor, John G. Hughes, warning 9, Prof. Hughes said: “Voluntary serious situation.” Hughes said that students should of impending “ nancial challenges” redundancy terms will be considered Hughes added: “ ere was a headline not feel the e ects of cuts, and that facing the institution. in speci c areas, but unfortunately, in e Times about three English instructions have been given to “protect PAGE 4-5 e letter cites the demographic the need for compulsory redundancies universities being close to bankruptcy. the student experience at all costs,” decline in 18-20 year-olds which has cannot be ruled out at this stage.” An important point is that Bangor is especially in “student facing areas.” impacted tuition fee revenues as a is letter comes 18 months a er nowhere near that. -

Five Walks in Search of the Future in Shanghai

The Hyperstationary State: Five Walks in Search of the Future in Shanghai By Owen Hatherley Abstract Shanghai is invariably used in film sets and popular discourse as an image of the future. But what sort of future can be found here? Is it a qualitative or quantitative advance? Is there any trace in the landscape of China's officially still-Communist ideology? Has the city become so contradictory as to be all-but unreadable? Contemporary Shanghai is often read as a purely capitalist spectacle, with the interruption between the colonial metropolis of the interwar years and the commercial megalopolis of today barely thought about. A sort of super-NEP has now visibly created one of the world's most visually capitalist cities, at least in its neon-lit night-time appearance and its skyline of competing pinnacles. Yet this seeming contradiction is invariably effaced, smoothed over in the reigning notion of the 'harmonious society'. This essay is a series of beginners' impressions of the city's architecture, so it is deeply tentative, but it finds hints of various non-capitalist built forms – particularly a concomitance with Soviet Socialist Realist architecture of the 1950s. It finds at the same time a dramatic cityscape of primitive accumulation, with extreme juxtapositions between the pre-1990s city and the present. Finally, in an excursion to the 2010 Shanghai Expo, we find two attempts to revive the language of a more egalitarian urban politics; in the Venezuelan Pavilion, an unashamed exercise in '21st century socialism'; and in the 'Future Cities Pavilion', which balances a wildly contradictory series of possible futures, alternately fossil fuel-driven and ecological, egalitarian and neoliberal, as if they could all happen at the same time. -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

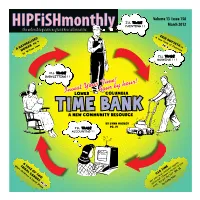

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists

Aichi Triennale 2019 Press Release _ Participating Artists As of March 27, 2019 Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists Aichi Triennale—an international contemporary art festival that occurs once every three years and is one of the largest of its kind—has been showcasing the cutting edge of the arts since 2010, through its wide-ranging program that spans international contemporary visual art, film, the performing arts, music, and more. This fourth iteration of the festival welcomes journalist and media activist Daisuke Tsuda as its artistic director. By choosing “Taming Y/Our Passion” as the festival’s theme, Tsuda seeks to address “the sensationalization of media that at present plagues and polarizes people around the world.” He hopes that by “employing the capacity of art— a venture that, capable of encompassing every possible phenomenon, eschews framing the world through dichotomies—to speak to our compassion, thus potentially yielding clues to solving this predicament.” Aichi Triennale 2019 announced the addition of 47 artists to its lineup on 27 March 2019; the list now comprises a total of 79 artists. Outline of Aichi Triennale 2019 http://aichitriennale.jp/ Theme | Taming Y/Our Passion Artistic Director | TSUDA Daisuke (Journalist / Media Activist) Period | August 1 (Thursday) to October 14 (Monday, public holiday), 2019 [75 days] Main Venues | Aichi Arts Center; Nagoya City Art Museum; Toyota Municipal Museum of Art and off-site venues in Aichi Prefecture, JAPAN Organizer | Aichi Triennale Organizing -

Artforum (May 9, 2019)

INTERESTING. Few words have such angular ambiguity, signifying both a viewer’s interpretive generosity while subtly acknowledging that the thing in question just might not be that good. Ralph Rugoff, the artistic director of the fifty-eighth Venice Biennale, which opened Tuesday to select press and professionals, played on the word’s double meaning in the title for his show, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” a phrase attributed as an “ancient Chinese curse,” but, like, the Ivanka Trump/fortune cookie variety, with no actual “ancient” or “Chinese.” The dash of Orientalism was either snarkily intentional from the start, or simply reclaimed as snarkily intentional after news of the title riled tempers east of the Urals. So how’s the exhibition itself? Interesting. Rugoff has packed his show of roughly eighty artists with whizzbang Instagrams-in-waiting, through an eclectic survey of exclusively living artists that felt more like someone had emptied Chelsea and the Lower East Side (the new, tonier one, not the one from seven years ago) into the Giardini’s Central Pavilion. But after a day of mulling it over, I decided this zeitgeist approach could be a throwback to the biennial’s days as a salon rather than a definitive statement on our life and times. Rugoff might argue that this is his point: In an age of “fake news” and myriad malleable perspectives, consensus is no longer possible. Even his exhibition is divided in two, with Proposition A in the Arsenale and Proposition B in the Giardini. In the absence of a strong thesis or even a clear curatorial vision, what we get is call and response. -

Download 2019 Annual Report

2019 | ANNUAL REPORT 1 Table of Contents Message from Message from President and Executive Director 3 the President Folklorama Talent 4 Folklorama Teachings 6 Folklorama Travel 7 & Executive Director Folklorama in the Community 9 2019 is a year that will go down in Folk- Folklorama Youth Council was engaged in Folklorama Youth Council 10 lorama history, confirming its role as a variety of 50th anniversary celebrations, Winnipeg’s anchor of summer tourism and and its Junior Pavilion Coordinators pro- Folklorama Festival 12 cultural outreach. The Folklorama family gram continues to grow, from 7 in 2017 to should be proud of the achievements we 18 in 2019. Learn more on page 10. The Pavilions 13 celebrated together for the 50th edition of the Folklorama Festival. The Talent, Teachings, and Travel divisions Volunteers 15 of the company continues to flourish The City of Winnipeg renamed Forks with bookings across North America, and Folklorama Ambassadors General 16 Market Road as Honourary Folklorama Way around the world. Turn to pages 4 to 6 to for the entire year to celebrate the Festi- learn more. Folklorama Ambassadors Program 18 val’s 50th. Dignitaries declared the name change at the annual media launch at The In 2019, Folklorama received a $100,000 Forks, a place where many cultures have grant from the federal government’s Al Malbranck Memorial Outstanding Volunteer Award 25 been meeting to celebrate and exchange Community Support for Multicultural and ideas for hundreds of years. Folklorama Anti-Racism Initiatives program. This grant Scholarships 26 was proud to unveil a legacy mural at 847 funded all special projects planned for the Notre Dame Avenue, to serve as a testa- milestone year. -

Renée Stout Born 1958, Junction City, Kansas Root Chart # 1, 2006 Graphite on Tracing Vellum Museum Purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Fund, 2008.0329

+ + Israhel van Meckenem the younger (1440 or 1445–1503) born Meckenheim, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany); died Bocholt, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany) after Master of the Housebook (circa 1470–1500) The Lovers, late 1400s engraving Gift of the Max Kade Foundation, 1969.0122 In the 15th century, gardens often inspired connotations of courtly love in chivalric medieval romances, poetry, and art. Sometimes referred to as gardens of love or pleasure gardens, these relatively private spaces offered respite from the very public arenas of court. Courtiers would use these gardens to sit, read, play games, roam the walkways, and have discreet meetings. Plants often contributed to the architecture of courtly gardens. Here, the suggestion of a grove sets the tone for the intimate activities of the couple. The smells of flowers and herbs, the colors of blooms and leaves, the sounds of birds, and of the running water of fountains all added to the sensuality of medieval pleasure gardens. + + + + Esaias van Hulsen (circa 1585–1624) born Middelburg, Dutch Republic (present-day Netherlands); died Stuttgart, Duchy of Württemberg (present-day Germany) Console of scrolling foliate forms with flowers and two birds, and a hunter shooting rabbits, circa 1610s engraving Museum purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Memorial Art Fund, 2013.0204 In this engraving van Hulsen carries on the longstanding ornament print tradition of imagining complex, elegant botanical structures. Ornament prints encourage viewers to search through the depicted foliage for partially hidden figures and forms. In this artwork viewers can find insects and birds. Van Hulsen adds a relatively orthodox landscape populated by a rabbit hunter, his dog, and their quarry to this fantastic realm of plants and animals. -

“Where the Mix Is Perfect”: Voices

“WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE by Carleton S. Gholz B.A., Macalester College, 1999 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Carleton S. Gholz It was defended on April 11, 2011 and approved by Professor Brent Malin, Department of Communication Professor Andrew Weintraub, Department of Music Professor William Fusfield, Department of Communication Professor Shanara Reid-Brinkley, Department of Communication Dissertation Advisor: Professor Ronald J. Zboray, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Carleton S. Gholz 2011 iii “WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE Carleton S. Gholz, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 In recent years, the city of Detroit’s economic struggles, including its cultural expressions, have become focal points for discussing the health of the American dream. However, this discussion has rarely strayed from the use of hackneyed factory metaphors, worn-out success-and-failure stories, and an ever-narrowing cast of characters. The result is that the common sense understanding of Detroit’s musical and cultural legacy tends to end in 1972 with the departure of Motown Records from the city to Los Angeles, if not even earlier in the aftermath of the riot / uprising of 1967. In “‘Where The Mix Is Perfect’: Voices From The Post-Motown Soundscape,” I provide an oral history of Detroit’s post-Motown aural history and in the process make available a new urban imaginary for judging the city’s wellbeing. -

1418780137179.Pdf

A WARHAMMER 40,000 NOVEL SOUL HUNTER Night Lords - 01 Aaron Dembski-Bowden (An Undead Scan v1.0) 1 Katie, will you marry me? 2 It is the 41st millennium. For more than a hundred centuries the Emperor has sat immobile on the Golden Throne of Earth. He is the master of mankind by the will of the gods, and master of a million worlds by the might of his inexhaustible armies. He is a rotting carcass writhing invisibly with power from the Dark Age of Technology. He is the Carrion Lord of the Imperium for whom a thousand souls are sacrificed every day, so that he may never truly die. Yet even in his deathless state, the Emperor continues his eternal vigilance. Mighty battlefleets cross the daemon-infested miasma of the warp, the only route between distant stars, their way lit by the Astronomican, the psychic manifestation of the Emperors will. Vast armies give battle in His name on uncounted worlds. Greatest amongst his soldiers are the Adeptus Astartes, the Space Marines, bio-engineered super-warriors. Their comrades in arms are legion: the Imperial Guard and countless planetary defence forces, the ever-vigilant Inquisition and the tech- priests of the Adeptus Mechanicus to name only a few. But for all their multitudes, they are barely enough to hold off the ever-present threat from aliens, heretics, mutants—and worse. To be a man in such times is to be one amongst untold billions. It is to live in the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable. These are the tales of those times.