Upk Simpson.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaska Story

COMPASS BEARINGS Gary Walter The Alaska Story his is the season for regional annual meet- our own fledgling movement, just four years old at ings. The Covenant, though one church, has the time, to step into the initiative in their place. The Televen regions within the United States and Covenant did, and Alaska became one of our very first Canada known as conferences. Each year delegates mission endeavors, along with China. The blight of a from churches within those areas gather to celebrate few early missionaries being sidetracked by the gold what God is doing and to deliberate on where God is rush notwithstanding, the emerging endeavor, joining leading. It is also a time to make new friendships and the efforts of Alaska Native leaders and missionaries, deepen old bonds. went on to develop churches, orphanages, schools, This year I traveled to the meeting of our Alaska and clinics over the first several decades. region, known as ECCAK (Evangelical Covenant Alaska is where the Covenant Church first grew Church of Alaska). Given the scope of what we do in multiethnic understanding. It hasn’t always been and the relatively small population of the state, Alaska easy, and it hasn’t always been done right. No one may be the only place in the United States and Cana- would deny that there have been hurtful, paternalistic, da where having heard of the Covenant is culturally and insensitive moments. But just because we haven’t normative—well, OK, at least not all that unusual. always gotten it right, doesn’t mean it isn’t right. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Put Your Foot Down

PAGE SIX-B THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 2012 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurniture Your Feed Stop By New & Used Furniture & Appliances Specialists Frederick & May For All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! QUALITY Refrigeration Needs With A •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. Regular •Superior Design and Quality Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FOR ALL Remember We Service 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOUR $ 00 $379 • Animal Health Products What We Sell! •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms • Pet Food & Supplies •Horse Tack FARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty • Farm & Garden Supplies •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty FINANCING AVAILABLE! (Moved To New Location Behind Save•A•Lot) Lumber Co., Inc. Williams Furniture 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. • WEST LIBERTY We Now Have A Good Selection 548 Prestonsburg St. • West Liberty, Ky. 7598 Liberty Road • West Liberty, Ky. TPAGEHE LICKING TWE LVVAELLEY COURIER THURSDAYTHURSDAY, NO, VJEMBERUNE 14, 24, 2012 2011 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Of Used Furniture Phone (606) 743-3405 Phone: (606) 743-2140 Call 743-3136 PAGEor 743-3162 SEVEN-B Holliday’s Stop By Your Feed Frederick & May OutdoorElam’sElam’s Power FurnitureFurniture Equipment SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New4191 & Hwy.Used 1000 Furniture • West & Liberty, Appliances Ky. -

A Flatlander's View of Flying Alaska

SAY AGAIN? THE FINANCE AND TAXES OF ATC MISCONCEPTIONS FLYING YOUR ECLIPSE FOR BUSINESS EJOPA EDITION THE PRIVATE JET SUMMER 2017 MAGAZINE A FLATLANDER’S VIEW OF FLYING ALASKA WHY GET MISSION ALL ABOUT UPSET? ACCOMPLISHED OSHKOSH UPSET TRAINING CIRRUS GETS EVEN BETTER EAA AIR VENTURE Contrails.EJOPA.indd 1 8/14/17 1:51 PM THIS IS EPIC. AIRCRAFT SALES & ACQUISITIONS MAXIMUM TIME TO CLIMB RANGE MAX RANGE ECO PAYLOAD AEROCOR has quickly become the world's number one VLJ broker, with more listings and CRUISE SL TO 34,000 CRUISE CRUISE (FULL FUEL) more completed transactions than the competition. Our success is driven by product 325 KTAS 15 Minutes 1385 NM 1650 NM 1120 lbs. specialization and direct access to the largest pool of light turbine buyers. Find out why buyers and sellers are switching to AEROCOR. ACCURATE INTEGRITY UNPARALLELED PRICING EXPOSURE Proprietary market Honest & fair Strategic partnership tracking & representation with Aerista, the world's valuation tools largest Cirrus dealer CALL US TODAY! (747)(747) 777-9505 777-9505 or [email protected] or [email protected] www.epicaircraft.com 541-639-4602 888-FLY-EPIC WWW .AEROCOR.COM Contrails.EJOPA.indd 2-3 8/14/17 1:51 PM THIS IS EPIC. AIRCRAFT SALES & ACQUISITIONS MAXIMUM TIME TO CLIMB RANGE MAX RANGE ECO PAYLOAD AEROCOR has quickly become the world's number one VLJ broker, with more listings and CRUISE SL TO 34,000 CRUISE CRUISE (FULL FUEL) more completed transactions than the competition. Our success is driven by product 325 KTAS 15 Minutes 1385 NM 1650 NM 1120 lbs. -

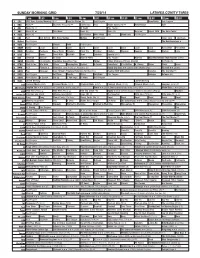

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Port Back on Comp Plan

Fifteen and done: Giants devastate Packers in Green Bay /B1 MONDAY CITRUS COUNTY TODAY & Tuesday morning HIGH Partly cloudy, winds 5 to 73 10 mph. Slight chance LOW of rain Tuesday. 47 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JANUARY 16, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 162 NEWS BRIEFS Port back on comp plan Government center to open CHRIS VAN ORMER As part of the groundwork Commissioners (BOCC) portation planner, ex- “One of the recommenda- Tuesday Staff Writer to conduct a feasibility conducted a transmittal plained the background for tions of the 1996 evaluation study for the proposed Port public hearing on the port the need to put back the appraisal report was to re- The new West Citrus Keeping the port project Citrus project, county staff element and voted unani- port element. Jones said the move the port element from Government Center in on course, commissioners on had to put the port element mously to authorize trans- original comprehensive the comprehensive plan,” Meadowcrest opens for Tuesday agreed to add an- back into the comprehen- mittal of the element to plan adopted in 1989 in- Jones said. “The board in business Tuesday other chapter to the county’s sive plan. The Citrus state agencies for review. cluded a ports and aviation morning. comprehensive plan. County Board of County Cynthia Jones, trans- element. See PORT/Page A4 The satellite offices for clerk of court, tax collec- tor, property appraiser and supervisor of elec- tions relocated from their old offices in a Crystal River shopping center on U.S. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Application of Affiliated Media, Inc. ) File No. BALCDT-20130125ABD FCC Trust, Assignor, and Denali Media ) Facility ID No. 49632 Anchorage, Corp., Assignee, For Consent ) to Assign the License of Station ) KTVA (TV), Anchorage, Alaska ) ) Application of Dan Etulain, Assignor, and ) File Nos. BALDTL-20130125AAL Denali Media Southeast, Corp., Assignee, ) & BALTVL-20130125AAK For Consent to Assign the Licenses of ) Facility ID Nos. 188833 & 15348 Stations KATH-LD, Juneau-Douglas, ) Alaska and KSCT-LP, Sitka, Alaska ) To: The Media Bureau OPPOSITION OF DENALI MEDIA ANCHORAGE, CORP., AND DENALI MEDIA SOUTHEAST, CORP., TO PETITION TO DENY Kurt Wimmer Eve R. Pogoriler Daniel H. Kahn COVINGTON & BURLING LLP 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004-2401 (202) 662-6000 Counsel for Denali Media Anchorage, Corp., and Denali Media Southeast, Corp. March 14, 2013 SUMMARY General Communication, Inc., here proposes to acquire one television station in Anchorage (KTVA) and two low-power stations in Juneau (KATH) and Sitka (KSCT) with the goal of attracting viewers with first-rate local programming. This small transaction will create large benefits for Alaska, which suffers from a stunning lack of broadcast competition, local news diversity, and technological innovation. GCI will invest heavily in local programming, more than doubling KTVA’s news offerings, hiring dozens of full-time news employees, and launching Alaska’s first high-definition local news. GCI has a 30-year history of bringing the benefits of competition to Alaska, investing more than $1 billion in the state to expand a variety of communications services, and forcing incumbents to improve their own services along the way. -

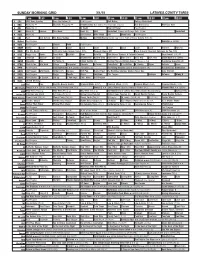

Sunday Morning Grid 7/20/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/20/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Paid Action Sports (N) Å Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Exped. Wild The Open Today 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program The Benchwarmers › 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Married Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Alemania. (N) Daddy Day Care ›› (2003) Eddie Murphy. (PG) Firewall ›› (2006) 50 KOCE Peg Dinosaur Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) Healing ADD With-Amen Favorites The Civil War Å 52 KVEA Paid Program Jet Plane Noodle Chica LazyTown Paid Program Enfoque Enfoque (N) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Ballgame Local teams go head to head in CAPE CORAL Bud Roth tourney DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Mostly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Cloudy — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 89 Friday, April 17, 2009 50 cents Cape man guilty on all counts in ’05 shooting death “I’m very pleased with the verdict. This is a tough case. Jurors deliberate for nearly 4 hours It was very emotional for the jurors, but I think it was the right decision given the evidence and the facts of the By CONNOR HOLMES tery with a deadly weapon. in the arm by co-defendant Anibal case.” [email protected] Gaphoor has been convicted as Morales; Jose Reyes-Garcia, who Dave Gaphoor embraced his a principle in the 2005 shooting was shot in the arm by Morales; — Assistant State Attorney Andrew Marcus mother, removed his coat and let death of Jose Gomez, 25, which and Salatiel Vasquez, who was the bailiff take his fingerprints after occurred during an armed robbery beaten with a tire iron. At the tail end of a three-day made the right decision. a 12-person Lee County jury found in which Gaphoor took part. The jury returned from approxi- trial and years of preparation by “I’m very pleased with the ver- him guilty Thursday of first-degree Several others were injured, mately three hours and 45 minutes state and defense attorneys, dict,” he said Thursday. “This is a felony murder, two counts of including Rigoberto Vasquez, who of deliberations at 8 p.m. -

Tv Pg 01-04-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, January 4, 2011 7 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening January 4, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC No Ordinary Family V Detroit 1-8-7 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS Live to Dance NCIS Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Glee Million Dollar Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC Demolition Man Demolition Man Crocodile Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike Animals Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET American Gangster The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show State 2 Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Matchmaker Matchmaker The Fashion Show Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local The Dukes of Hazzard The Dukes of Hazzard Canadian Bacon 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Daily Colbert Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Futurama Local 9 NBC-KUSA 37 USA 65 We DISC Local Local Dirty Jobs -

Emerging from the Shadows: Civil War, Human Rights, And

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Department Theses and Anthropology, Department of Dissertations Summer 6-16-2014 EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS: CIVIL WAR, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND PEACEBUILDING AMONG PEASANTS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN COLOMBIA AND PERU IN THE LATE 20TH AND EARLY 21ST CENTURIES Charles A. Flowerday University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Community Psychology Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Counseling Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Folklore Commons, Health Psychology Commons, History of Christianity Commons, International Relations Commons, Multicultural Psychology Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Flowerday, Charles A., "EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS: CIVIL WAR, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND PEACEBUILDING AMONG PEASANTS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN COLOMBIA AND PERU IN THE LATE 20TH AND EARLY 21ST CENTURIES" (2014). Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations. 33. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS: CIVIL WAR, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND PEACEBUILDING AMONG PEASANTS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN COLOMBIA AND PERU IN THE LATE 20TH AND EARLY 21ST CENTURIES by Charles A.