Corduroy Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact Fee Study Also Called for a Multimillion Dollar Indoor Facility but the Project Did Not Materialize Over the Last 10 Years

Town of Amherst Impact Fees 2020 Basis of Assessment and Fee Schedules Public Schools Police Fire-Rescue Recreation Town Roads June 3, 2020 Prepared for: Town of Amherst 2 Main Street Amherst, New Hampshire 03031 Prepared by: P. O. Box 723 Yarmouth, ME 04096 [email protected] Table of Contents A. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 B. Impact Fee Principles ............................................................................................................................... 3 1. Conditions for Impact Fee Assessment ................................................................................................. 3 2. Impact Fee Assessment, Collection, and Retention ............................................................................. 3 3. Units of Assessment ............................................................................................................................. 4 C. Proportionate Demand Measures ........................................................................................................... 5 1. Residential Development Trend........................................................................................................... 5 2. Employment and Commercial Development Trend ............................................................................ 8 D. Public Safety Impact Fees ..................................................................................................................... -

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003 Property Information � 15,000 SF of retail/office space available | Can be subdivided to 7,000 SF � Former corporate headquarters with custom finished board room and multiple executive offices � Potential build-to-suit - 8,000 SF of office/retail space � Local loan/incentive packages available for relocations � Well maintained commercial space � Elevator served � Signage opportunity on National Road � Over 50 on-site parking spaces � Located in the heart of the Marcellus and Utica Gas Shale region � Close Proximity to US Route 40, Interstate 70, Interstate 470,West Virginia Route 2 & West Virginia Route 88 For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Century Centre � 1233 Main Street, Suite 1500 � Wheeling, WV 26003 960 Penn Avenue, Suite 1001 � Pittsburgh, PA 15222 304.232.5411 � www.century-realty.com SITE I-70 On Ramp 8,000 Vehicles/Day I-70 47,000 Vehicles/Day Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. All property information should be confirmed before any completed transaction. For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Expansion Space or Drive Thru Potential Drive Thru 8,000 SF Wheeling The 30 Miles to Highlands Washington, PA Pittsburgh Approximately Wheeling 38 Miles Columbus Approximately 136 Miles Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. -

Transportation and Community and Systems Preservation Study

TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITY AND SYSTEMS PRESERVATION STUDY AMHERST, NEW HAMPSHIRE July, 2006 Prepared by the Nashua Regional Planning Commission Transportation and Community and Systems Preservation Study for Amherst, New Hampshire July, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................I-1 A. THE ISSUES ................................................................................................................................. I-1 B. STRATEGIES ................................................................................................................................ I-1 C. NEXT STEPS ................................................................................................................................ I-2 CHAPTER II: INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................II-1 A. ORIGIN OF THE TCSP STUDY.................................................................................................... II-1 B. NRPC ROLE.............................................................................................................................. II-2 C. STUDY PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ II-2 D. REPORT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................... II-2 CHAPTER III: TRAFFIC -

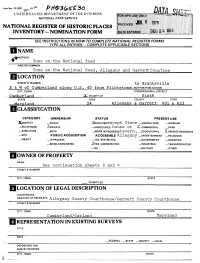

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

:orm No. 10-300 ^0'' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME •^HISTORIC Inns on the National Road AND/OR COMMON Inns on the National Road, Allegany and GarrettCounties LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER to Grantsville & W of Cumberland, a^ong U.S. 40 from Flintstone-NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT .Cumberland Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 24 Alleaanv & Garrett 001 & 023 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE XDISTRICT —PUBLIC —XoccupiEDexcept Stone _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _=j8UILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED house or X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _woRKiNpROGRESstavern, —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE Allegany —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME See continuation sheets 3 and STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Allegany County Courthouse/Garrett County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Maryland 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGrNAL SITE GOOD XRUINS only Stone ALTERED MOVED r»ATF *A.R _ UNEXPOSED house or tavern, Allegany DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Eleyen of the inns that served the National Road and the Baltimore Pike in Allegany and Sarrett Counties, Maryland, during the 19th century re main today. ALLEGANY COUNTY The Flints tone Hot e 1 stands on the north side of old Route 10 to the east of Hurleys Branch Road in Flintstone. -

10-26-2020 Joint

VILLAGE OF ESSEX JUNCTION TRUSTEES Online TOWN OF ESSEX SELECTBOARD Essex Junction, VT 05452 Monday, October 26, 2020 SPECIAL MEETING AGENDA 6:30 PM E-mail: [email protected] www.essexjunction.org Phone: (802) 878-1341 www.essexvt.org (802) 878-6951 Due to the Covid -19 pandemic, this meeting will be held remotely. Available options to watch or join the meeting: • WATCH: the meeting will be live-streamed on Town Meeting TV. • JOIN ONLINE : Join Microsoft Teams Meeting. Depending on your browser, you may need to call in for audio (below). • JOIN CALLING : Join via conference call (audio only): (802) 377-3784 | Conference ID: 142 554 11# • PROVIDE FULL NAME: For minutes, please provide your full name whenever prompted. • CHAT DURING MEETING: Please use “Chat” to request to speak, only. Please do not use for comments. • RAISE YOUR HAND: Click on the hand in Teams to speak or use the “Chat” feature to request to speak. • MUTE YOUR MIC: When not speaking, please mute your microphone on your computer/phone. The Selectboard and Trustees meet together to discuss and act on joint business. Each board votes separately on action items. 1. CALL TO ORDER [6:30 PM] 2. AGENDA ADDITIONS/CHANGES 3. APPROVE AGENDA 4. PUBLIC TO BE HEARD a. Comments from Public on Items Not on Agenda 5. BUSINESS ITEMS a. Approve Town of Essex / Village of Essex Junction Public Works Winter Operations Plan with COVID 19 Impacts 2020-2021 b. Accept traffic study with change in speed limit from 30 mph to 25 mph on Sand Hill Road near Founders Road (Selectboard only) c. -

February 7 and 14, 2008 LOCATION of CONFERENCES

BUREAU OF ENVIRONMENT CONFERENCE REPORT DATE OF CONFERENCES: February 7 and 14, 2008 LOCATION OF CONFERENCES: J.O. Morton Building ATTENDED BY: Sarah Graulty, Christine Perron, Kevin Nyhan, Cathy Goodmen, Charles Hood, Marc Laurin, Mark Hemmerlein, Matt Urban, Phil Miles, Lisa Denoncourt, and Chris Waszczuk, NHDOT; Dick Boisvert and Beth Muzzey, NHDHR; Jamie Sikora, FHWA; Joe Klementovich, HEB; Jamie Paine, CLD; Cole Melendy and Rene LaBranch, Stantec; Gene McCarthy and Vicki Chase, MJ Inc.; Liz Hengen, Preservation Consultant; and Deb Loiselle, Jim Gallagher, Grace Levergood, and Steve Doyon, DES. SUBJECT: Monthly SHPOFHWAACOENHDOT Cultural Resources Meeting Tuftonboro Rochester Hudson, STPTEX5229(013), 13100 Auburn Nashua, XA000(006), 10136A Concord XA000(566), 14426 Pelham, XA000(415), 14491 Bartlett 14372 Seabrook 12630 PortsmouthDoverRochester 15304 SalemManchester, IMIR0931(174), 10418C Connecticut River Scenic Byway Phase I Nashua (Litchfield) 10644 Wakefield 14871 NHDESDam Bureau Thursday, February 7, 2008 Tuftonboro (no project numbers). Participant: Joe Klementovich, HEB Engineers ( [email protected]); Sue Weeks, Chair, Selectperson, Town of Tuftonboro, and Dick Boisvert, NHDHR The historical and archaeological impacts created by the replacement of four culverts and the re aligning of 1400 feet of Lang Pond Road which parallels Mirror Lake were examined. Joe Klementovich presented an overview of the project and the scope of work proposed for the improvements along Lang Pond Rd. Sue Weeks, the chair of the Tuftonboro Board of Selectman, presented historical aerial photographs, maps and documents relating to Native American trails in the area and identified the corridor as the Governor Wentworth Highway. -

Western Pennsylvania History Spring 2016

Up Front This advertisement informs travelers about passage on the National Road Stage Company’s line of coaches. The Reporter, July 22, 1843. sheep, and pigs from western farms to the Meadowcroft markets of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Wagoners could transport salt, sugar, tea, By Mark Kelly coffee, and iron to western settlements, then Meadowcroft Interpreter/Tour Guide return with whiskey, wool, flour, and bacon much more efficiently in their Conestoga wagons.3 Even though this improved route Carried in Comfortable Coaches made the journey easier for many, the pace Hagerstown, Maryland. An ad in Washington, of travel was still only a few miles an hour. Pa.’s The Reporter on April 30, 1821, states,“The In 1806, Thomas Jefferson signed “An Act to For those who could afford it, stage coaches arrangement of this line, will secure a Regulate the Laying Out and Making a Road offered speedy travel between cities in the East passenger a safe conveyance from Wheeling to from Cumberland in the State of Maryland, to and the Midwest. Philadelphia (a distance of 346 miles) in a little the State of Ohio.”1 This road would ease the The earliest stage lines spanned the more than four days.”6 The pair continued to journey of settlers moving west by improving 131-mile-trip from Cumberland to Wheeling expand their operations west, establishing the part of the existing road cut by British in four different sections, but ran only three National Road Stage Company in Uniontown General Edward Braddock in 1755, and link times each week.4 These original lines, bought around 1824. -

Lucas County Engineers Office Keith G

Lucas County Engineers Office Keith G. Earley, P.E., P.S., Lucas County Engineer Richfield Center Road—Brint Road to Sylvania- Metamora Road Raab Road Bridge #275 Decant Road—Brown Road to S.R. 2 1 Hertzfeld Road—U.S. 24 to Vollmer Road Holloway Road—Salisbury Road to Garden Road Brown Road—Nissen Road to Turnau Road Lucas County Engineer’s Office JUNE 1st, 2012 One Government Center Responsible Action is Necessary A good highway system is a vital component of our economic prosperity. Suite 870 We depend on it to perform our daily commercial and personal activities. If we Toledo, Ohio 43604-2258 hope to maintain or improve our infrastructure, a suitable level of financial invest- ment is required. In Lucas County, our dedicated revenue for county maintained Phone: 419-213-4540 roads and bridges is slightly less than it was twelve years ago while overall costs Road Maintenance Department have increased over 50%, some costs such as asphalt paving have more than dou- bled, and the situation is similar across the state. We have reduced our workforce 2504 Detroit Avenue by 35%, and many people have taken on additional duties. We are doing what we Maumee, Ohio 43537 can to reduce our long term operating costs, to free up money for roadway preser- vation and improvement projects. We would like to make improvements that INSIDE THIS REPORT would last 15 years or more, but financial conditions have forced us to rely on pres- Responsibilities of the Engineer 3 ervation projects that will probably only last three to eight years. -

Harvard Pond

HARVARD POND: NATURAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY Prepared by Robert A. Clark 1889 SELECTED POINTS OF INTEREST 5 4 3 6 2 7 8 1 9 10 11 © Map courtesy of Harvard Forest – Modified A PLACE OF MANY NAMES: MEADOW WATER – BROOKS POND WEST POND – HARVARD POND 1 Ezra Pike's home. Just north is the dam and outflow from Harvard Pond, East Branch Fever Brook. Immediately north of the dam, between the pond and the road, is the site of a steam powered saw mill used to cut logs from trees downed by the 1938 hurricane. 2 A mystery farm – land use history with a red pine and European larch plantation which was cut in 2008. 3 Sawmill owned by the Southworth brothers of Hardwick in 1850. This mill cut the lumber for the new Town House (Town Hall) built in 1850. The mill was removed in 1865. 4 Mr. Gilson's home. Mr. Gilson probably sawed the lumber for the new Town House in 1850 which burned in 1957. On the north side of Tom Swamp Road was the home of William Pierce which was later the home of Deacon Levi Babbett. 5 Tom Swamp – an ancient red spruce, black spruce, tamarack quaking bog. The raised road (causeway ) over the wetlands is a corduroy road and the gravel that covers the logs which were laid crosswise in a ribbed pattern (hence corduroy) was taken from the borrows just east of the causeway. 6 Richard Thornton Fisher memorial – Richard Thornton Fisher was the first director of Harvard Forest. His memorial is located at one of his favorite spots of old growth forest overlooking the pond which was unfortunately devastated by the 1938 hurricane. -

National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926

National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926 Library of Congress The National Road, in many places now known as Route 40, was built between 1811 and 1834 to reach 1910 photo of the National Road, the western settlements. It was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. George Washington and 1.5 miles west Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary for unifying the young country. of Brownsville, In 1806, Congress authorized construction of the road, and President Jefferson signed the act establish- Pennsylvania. ing the National Road. In 1811, the first contract was awarded, and the first 10 miles of road were built. As work on the road progressed, a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages are still found along the National Road. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike, and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning it the nickname “The Main Street of America.” In the 1800s, it was a key transport path to the West for thousands of settlers. In 1912, the road became part of the National Old Trails Road, and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926, the road became part of U.S. 40 as a coast-to-coast highway running from Atlantic City to San Francisco. Contributions & Crossroads Our National Road System’s Impact on the U.S. Economy and Way of Life National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926 Public domain photo by Lyle Kruger A section of Route 40 (above) with its original paving bricks stretches out to the horizon. -

The National Road

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Necessity National Battlefield The National Road piznnsgivania ^ Illinois 0) Mount ashlngton Tavern Indiana ^ A \ W Va. (\?irginia KizntueRu till National Road, built by federal funds,600 mnes Baltimore Pike, buit by private funds Virginia Missouri Proposed but not constructed The National Road, designated U.S. Route 40 in 1925, was the first highway built entirely with federal funds. The road was authorized by Congress in 1806 during the Jefferson Administration. Construction began in Cumberland, Maryland in 1811. The route closely paralleled the military road opened by George Washington and General Braddock in 1754-55. S By 1818,the road had been completed to the Ohio River at Wheeling, which was then in Virginia. Eventually the road was pushed through central Ohio and Indiana, reaching Vandalia,Illinois in the 1830s where construction ceased due to a lack offunds. The National Road opened the Ohio River Valley and the Midwest for settlement and commerce. Traveling The opening of the road saw thousands of travelers Taverns were probably the heading west over the Allegheny Mountains to most important and numerous businesses found on settle the rich land of the Ohio River Valley. Small the National Road. It is estimated there was about towns along the National Road's path began to one tavern every mile on the National Road. There grow and prosper with the increase in population. were two different classes of taverns on the road. Towns such as Cumberland, Uniontown, The stagecoach tavern was one type. It was the Brownsville, Washington,and Wheeling evolved more expensive accommodation, designed for the into commercial centers of business and industry. -

THE NATIONAL ROAD the Road to Allegany and Garrett County History

42 m o u n t a i n d i s c o v e r i e s THE NATIONAL ROAD The Road to Allegany and Garrett County History Written by: Dan Whetzel Photography by: Lance C. Bell Western Maryland received a major economic As military operations of the French and Indian and boost in 1806, and secured a place in American history, Revolutionary Wars subsided, the young nation directed when Cumberland was selected as the starting point for its attention to economic enterprises. Calls for improved the National Road, America’s first federally funded highway roads were issued by commercial interests and land speculators that eventually stretched from Cumberland, Maryland who realized the monetary rewards of accessing natural to Vandalia, Illinois. The road was also called The National resources in western territories. Manufactured goods moving Turnpike and Cumberland Road. Several general reasons westward benefited the settlers who also sought access to favored construction of the road in Maryland, including eastern markets for their crops and raw materials. Before geography, land speculation, and economic pressures from roads, all commerce between the interior and the east coast western settlers. Cumberland was also a logical choice for had to be by a water route down the Ohio and Mississippi the new highway as it was already connected to the port Rivers, through the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, and city of Baltimore by an existing road, commonly called the then up the coast. Mutually beneficial interests caused Cumberland Road, and because British General Edward a consensus to be formed regarding the need for better Braddock used it as a base of operation in his highly pub- roads, but the funds to finance them remained elusive.