Our Hidden Borders: the UK Border Agency Powers of Detention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration, (2021)

Right to respect for private and family life: immigration, (2021) Right to respect for private and family life: immigration Last date of review: 02 March 2021 Last update: General updating. Authored by Austen Morgan 33 Bedford Row Chambers Convention rights - from the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and given further effect by scheduling to the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) have applied incontrovertibly in domestic UK law since 2 October 2000. There was considerable discussion from 1997 about which rights would be litigated in future years, on the basis of the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) at Strasbourg, in the three jurisdictions of the United Kingdom (UK): England and Wales; Scotland; and Northern Ireland. Some commentators anticipated that art.8 (the right to respect for private and family life) would be important, as the basis of a new domestic right to privacy. Few, if any, predicted that the family life aspect of art.8 would play a significant role in UK immigration law and practice; this regulates the entry (and possibly exit) of non-nationals, whether as visitors, students, workers, investors or residents. Overview of Topic 1. This article looks at legislative, executive and judicial attempts to limit such art.8 cases since 2000, a project led by successive Secretaries of State (SoS) for the Home Department, of whom there have been six Labour, one coalition Conservative and three Conservatives in the past 20 years. 2. It considers the following topics: the structure of art.8 in immigration cases; how the SoS might theoretically limit its effect in tribunals and courts; the failed attempt to do so through the Immigration Rules; the slightly more successful attempt to do so through statute; the mixed response of the senior judiciary; and future prospects. -

Public Law and Civil Liberties ISBN 978-1-137-54503-9.Indd

Copyrighted material – 9781137545039 Contents Preface . v Magna Carta (1215) . 1 The Bill of Rights (1688) . 2 The Act of Settlement (1700) . 5 Union with Scotland Act 1706 . 6 Official Secrets Act 1911 . 7 Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 . 8 Official Secrets Act 1920 . 10 The Statute of Westminster 1931 . 11 Public Order Act 1936 . 12 Statutory Instruments Act 1946 . 13 Crown Proceedings Act 1947 . 14 Life Peerages Act 1958 . 16 Obscene Publications Act 1959 . 17 Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1967 . 19 European Communities Act 1972 . 24 Local Government Act 1972 . 26 Local Government Act 1974 . 30 House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 . 36 Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 . 38 Highways Act 1980 . 39 Senior Courts Act 1981 . 39 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 . 45 Public Order Act 1986 . 82 Official Secrets Act 1989 . 90 Security Service Act 1989 . 96 Intelligence Services Act 1994 . 97 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 . 100 Police Act 1996 . 104 Police Act 1997 . 106 Human Rights Act 1998 . 110 Scotland Act 1998 . 116 Northern Ireland Act 1998 . 121 House of Lords Act 1999 . 126 Freedom of Information Act 2000 . 126 Terrorism Act 2000 . 141 Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 . 152 Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 . 158 Police Reform Act 2002 . 159 Constitutional Reform Act 2005 . 179 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 . 187 Equality Act 2006 . 193 Terrorism Act 2006 . 196 Government of Wales Act 2006 . 204 Serious Crime Act 2007 . 209 UK Borders Act 2007 . 212 Parliamentary Standards Act 2009 . 213 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 . 218 European Union Act 2011 . -

1 UK BORDERS ACT 2007 1 the Act Received Royal Assent on 30 October 2007. the Following Are the Acts on the Subject of Immigrati

Briefing Paper 8.21 www.migrationwatchuk.org UK BORDERS ACT 2007 1 The Act received Royal Assent on 30 October 2007. The following are the Acts on the subject of immigration and asylum currently on the statute book: Immigration Act 1971 Immigration Act 1988 Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act 1993 Asylum and Immigration Act 1996 Special Immigration Appeals Commission Act 1997 Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc.) Act 2004 Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 UK Borders Act 2007 2 Each Act since 1971 has heavily amended earlier Acts and introduced substantial new provisions, with the result that legislation on these topics is diffuse and complex. There is a desperate need for a consolidation Act to tidy up the law, but there is no sign of that as yet. Anyone practising in the field must also take into account the Human Rights Act 1998, the Race Relations Act 1976 and the British Nationality Act 1981. 3 The title “UK Borders Act” marks a complete change from earlier nomenclature, but this is deceptive. The purpose described in its long title is “to make provision about immigration and asylum: and for connected purposes.” It contains an assortment of sections amending existing legislation and introducing new measures. Its main provisions are: (i) New powers of detention for immigration officers at ports. (ii) New powers enabling the Home Secretary to make regulations requiring persons subject to immigration control to apply for a document recording external physical characteristics - a “biometric immigration document”. (iii) New and drastic procedures for the deportation of foreign criminals, obviously prompted by revelations about the shortcomings of existing procedures which came to light during 2006. -

Working with the UK Border Agency and Border Force

This document was archived on 31 March 2016 Working with the UK Border Agency and Border Force archived This document was archived on 31 March 2016 Working with the UK Border Agency and Border Force UKBA works with key partner organisations Important facts Background to address key threats to the UK. These are the threats from: Controlling migration On 1 March 2012 Border Force was split from UKBA to become a separate law • terrorists; The Home Office is responsible for controlling enforcement command, led by its own migration to the UK, through the work of Border Force, Director General, and accountable directly to • criminals enabling illegal immigration which applies immigration and customs controls on Ministers. through fraud, forgery or other passengers arriving at the border, and of the UK Border organised attempts to cheat the Agency (UKBA). UKBA UKBA will protect the border and ensure that immigration system; Britain remains open for business, checking • processes visa applications overseas and people travelling to the UK before they arrive • organised illegal immigration to the applications for further stay from those already through visa checks, intelligence and the use UK; and, in the country, including students, workers, of the e-Borders system. family members and asylum seekers; • a crisis in another country that could At an operational level, Border Force ports lead to false or unfounded claims for • processes citizenship applications; and have local arrangements with the police, in asylum alongside legitimate refugee particular Special Branch, and, in Northern claims. • takes enforcement action against those found Ireland, the C3 Ports Policing Branch, for to be in the UK unlawfully. -

Home Office the Response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman Investigation Into a Complaint by Mrs a and Her Family About the Home Office

Home Office The response to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman investigation into a complaint by Mrs A and her family about the Home Office January 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................... 2 Foreword by the Permanent Secretary .................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ................................................................................................................. 5 Summary of recommendations ................................................................................................ 6 Background to the PHSO Report ............................................................................................. 9 Current Home Office structure ........................................................................................... 10 The PHSO Report .............................................................................................................. 10 Section 1: PHSO Recommendation 1 .................................................................................... 13 Overview of Section 1 ........................................................................................................ 13 The visa issuing process – self declaration and criminal history ........................................ 13 Procedures when a criminal record is declared .................................................................. 13 -

An Inspection of E-Borders October 2012 – March 2013

‘Exporting the border’? An inspection of e-Borders October 2012 – March 2013 John Vine CBE QPM Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration Our Purpose We provide independent scrutiny of the UK’s border and immigration functions to improve their efficiency and effectiveness. Our Vision To drive improvement within the UK’s border and immigration functions, to ensure they deliver fair, consistent and respectful services. All Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration inspection reports can be found at: www.independent.gov.uk/icinspector Email us: [email protected] Write to us: Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, 5th Floor, Globe House, 89 Eccleston Square, London, SW1V 1PN United Kingdom Contents FOREWORD 2 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Summary of Recommendations 7 3. The Inspection: In order to assist readers we have provided a summary of the key terms used in this report. 8 4. Background 11 5. Passenger Data 16 6. The National Border Targeting Centre 22 7. How e-Borders is used at ports of entry 32 8. Have the benefits of e-Borders been realised? 36 Appendix A – Inspection Framework and Criteria 45 Appendix B – Statutory Basis for e-Borders 46 Appendix C – Glossary 47 Acknowledgements 51 1 FOREWORD FROM JOHN VINE CBE QPM INDEPENDENT CHIEF INSPECTOR OF BORDERS AND IMMIGRATION The e-Borders programme has been in development for over a decade now, and has cost nearly half a billion pounds of public money, with many millions more to be invested over the coming years. The intention of e-borders was to ‘export the border’ by preventing passengers considered a threat to the UK from travelling, as well as delivering more efficient immigration control. -

12730 Analysis of Law in UK BRX:Layout 1

Analysis of Law in the United Kingdom pertaining to Cross-Border Disaster Relief Prepared for the British Red Cross by The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the British Red Cross. This report is part of a wider study on cross-border disaster assistance within the EU, carried out in conjunction with five other European National Societies, under the overall co-ordination of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The wider project received funding from the European Commission, who bear no responsibility for the content or use of the information contained in this report. Front cover photograph © Layton Thompson/British Red Cross Flood relief measures in Oxford, 25 July 2007 Analysis of Law in the United Kingdom pertaining to Cross-Border Disaster Relief Foreword The United Kingdom is in the fortunate position of Fisher (International Federation of Red Cross and Red being less susceptible to large-scale natural disasters Crescent Societies), Mr Tim Gordon (HMRC), Mr than many other countries. Even so, and as recent Gordon MacMillan (Hanover Associates UK), Mr Roy years have shown, our territory may still be subject to Wilshire (Chief Fire Officer, Hertfordshire County) such emergencies as flooding, and the effects of severe and Ms Moya Wood-Heath (British Red Cross). winter weather. We also wish to thank the authors of this report, The purpose of this study, commissioned by the British Justine Stefanelli and Sarah Williams of the British Red Cross, is to examine the extent to which the legal, Institute of International and Comparative Law, administrative and operational framework for disaster who were assisted by Katharine Everett, Frances response within the UK is able to facilitate potential McClenaghan, Hidenori Takai and Payam Yoseflavi. -

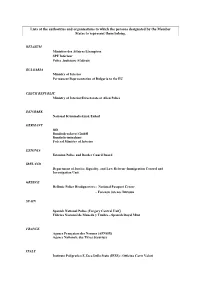

Lists of the Authorities and Organisations to Which the Persons Designated by the Member States to Represent Them Belong

Lists of the authorities and organisations to which the persons designated by the Member States to represent them belong. BELGIUM Ministère des Affaires Etrangères SPF Intérieur Police Judiciaire Fédérale BULGARIA Ministry of Interior Permanent Representation of Bulgaria to the EU CZECH REPUBLIC Ministry of Interior/Directorate of Alien Police DENMARK National Kriminalteknisk Enhed GERMANY BSI Bundesdruckerei GmbH Bundeskriminalamt Federal Ministry of Interior ESTONIA Estonian Police and Border Guard Board IRELAND Department of Justice, Equality, and Law Reform -Immigration Control and Investigation Unit GREECE Hellenic Police Headquarters - National Passport Center - Forensic Science Division SPAIN Spanish National Police (Forgery Central Unit) Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre - Spanish Royal Mint FRANCE Agence Françaises des Normes (AFNOR) Agence Nationale des Titres Sécurisés ITALY Instituto Poligrafico E Zeca Dello Stato (IPZS) - Officina Carte Valori CYPRUS Ministry of Foreign Affairs LATVIA Ministry of Interior - Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs Embassy of Latvia LITHUANIA Ministry of Foreign Affairs LUXEMBOURG Ministère des Affaires Etrangères HUNGARY Special service for national security MALTA Malta Information Technology Agency Ministry of Foreign Affairs NETHERLANDS Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken Ministerie van Justitie Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations AUSTRIA Österreichische Staatsdruckerei Abt. II/3 (Fremdenpolizeiangelegenheiten) POLAND Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of Consular Affairs -

The Points Based System

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Managing Migration: The Points Based System Thirteenth Report of Session 2008–09 Volume I HC 217-I House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Managing Migration: The Points Based System Thirteenth Report of Session 2008–09 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 15 July 2009 HC 217-I Published on 1 August 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chairman) Tom Brake MP (Liberal Democrat, Carshalton and Wallington) Ms Karen Buck MP (Labour, Regent’s Park and Kensington North) Mr James Clappison MP (Conservative, Hertsmere) Mrs Ann Cryer MP (Labour, Keighley) David TC Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Mrs Janet Dean MP (Labour, Burton) Patrick Mercer MP (Conservative, Newark) Margaret Moran MP (Labour, Luton South) Gwyn Prosser MP (Labour, Dover) Bob Russell MP (Liberal Democrat, Colchester) Martin Salter MP (Labour, Reading West) Mr Gary Streeter MP (Conservative, South West Devon) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

UK Borders Bill

UK Borders Bill [AS AMENDED IN PUBLIC BILL COMMITTEE] CONTENTS Detention at ports 1 Designated immigration officers 2 Detention 3 Enforcement 4 Interpretation: “port” Biometric registration 5 Registration regulations 6 Regulations: supplemental 7 Effect of non-compliance 8 Use and retention of information 9Penalty 10 Penalty: objection 11 Penalty: appeal 12 Penalty: enforcement 13 Penalty: code of practice 14 Penalty: prescribed matters 15 Interpretation Treatment of claimants 16 Conditional leave to enter or remain 17 Support for failed asylum-seekers 18 Support for asylum-seekers: enforcement 19 Points-based applications: no new evidence on appeal 20 Fees Enforcement 21 Assaulting an immigration officer: offence 22 Assaulting an immigration officer: powers of arrest, &c. 23 Seizure of cash 24 Forfeiture of detained property 25 Disposal of property 26 Employment: arrest 27 Employment: search for personnel records 28 Facilitation: arrival and entry Bill 82 54/2 ii UK Borders Bill 29 Facilitation: territorial application 30 People trafficking Deportation of criminals 31 Automatic deportation 32 Exceptions 33 Timing 34 Appeal 35 Detention 36 Family 37 Interpretation 38 Consequential amendments Information 39 Supply of Revenue and Customs information 40 Confidentiality 41 Wrongful disclosure 42 Supply of police information, etc. 43 Search for evidence of nationality 44 Seizure of nationality documents Border and Immigration Inspectorate 45 Establishment 46 Chief Inspector: supplemental 47 Reports 48 Plans 49 Relationship with other bodies: general 50 Relationship with other bodies: non-interference notices 51 Abolition of other bodies 52 Prescribed matters 53 Senior President of Tribunals General 54 Money 55 Repeals 56 Commencement 57 Extent 58 Citation Schedule — Repeals UK Borders Bill 1 A BILL [AS AMENDED IN PUBLIC BILL COMMITTEE] TO Make provision about immigration and asylum; and for connected purposes. -

Border Wars the Arms Dealers Profiting from Europe’S Refugee Tragedy

BORDER WARS THE ARMS DEALERS PROFITING FROM EUROPE’S REFUGEE TRAGEDY Mark Akkerman Stop Wapenhandel www.stopwapenhandel.org Border wars | 1 AUTHOR: Mark Akkerman EDITORS: Nick Buxton and Wendela de Vries DESIGN: Evan Clayburg PRINTER: Jubels Published by Transnational Institute – www.TNI.org and Stop Wapenhandel – www.StopWapenhandel.org Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is properly cited. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy or link of the text in which this document is used or cited. Please note that for some images the copyright may lie elsewhere and copyright conditions of those images should be based on the copyright terms of the original source. http://www.tni.org/copyright ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Corporate European Observatory for some of the information on arms company lobbying. Border wars: The arms players profiting from Europe’s refugee crisis | 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction: the EU war on immigration 3 Fueling the refugee tragedy: EU arms exports 6 EU response to migration: militarising the borders 9 – ‘Fighting illegal immigration’ – EUNAVFOR MED – Armed forces at the borders – NATO assistance – Border fences and drones – From Frontex to a European Border and Coast Guard Agency – Externalizing EU borders – Deal with Turkey – Selling militarisation as a humanitarian effort Lobbying for business 17 – Lobby organisations – Frontex and industry – Security fairs as meeting points EU funding for border security and border control 25 – Funding for (candidate) member states – Funding third countries’ border security – EU Research & Technology funding – Frontex funding for research – Future prospects for security research Which companies profit from border security? 34 – Global border security market – Frontex contracts – Major profiting companies – Detention and deportation Conclusion 43 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The refugee crisis facing Europe has caused consternation in the corridors of power, and heated debate on Europe’s streets. -

UK Border Security

WWW.IPPR.ORG UKBorderSecurity: Issues,systemsandrecentreforms AsubmissiontotheipprCommissiononNationalSecurityforthe21stCentury byFrankGregory ProfessorofEuropeanSecurityandJeanMonnetChairinEuropeanPoliticalIntegration,University ofSouthampton March2009 ©ippr2009 InstituteforPublicPolicyResearch Challengingideas– Changingpolicy 2 ippr|UKBorderSecurity:Issues,systemsandrecentreforms Aboutippr TheInstituteforPublicPolicyResearch(ippr)istheUK’sleadingprogressivethinktank,producing cutting-edgeresearchandinnovativepolicyideasforajust,democraticandsustainableworld.Since 1988,wehavebeenattheforefrontofprogressivedebateandpolicymakingintheUK.Throughour independentresearchandanalysiswedefinenewagendasforchangeandprovidepracticalsolutions tochallengesacrossthefullrangeofpublicpolicyissues. WithofficesinbothLondonandNewcastle,weensureouroutlookisasbroad-basedaspossible, whileourinternationalandmigrationteamsandclimatechangeprogrammeextendourpartnerships andinfluencebeyondtheUK,givingusatrulyworld-classreputationforhighqualityresearch. ippr,30-32SouthamptonStreet,LondonWC2E7RA.Tel:+44(0)2074706100E:[email protected] www.ippr.org.RegisteredCharityNo.800065 ThispaperwasfirstpublishedinMarch2009.©ippr2009 ipprCommissiononNationalSecurity TheipprCommissiononNationalSecurityisanall-partyCommissionpreparinganindependent nationalsecuritystrategyfortheUK.Itisco-chairedbyLordRobertsonofPortEllenandLord AshdownofNorton-sub-Hamdon.ThefullCommissionmembershipincludes: •LordPaddyAshdown,Co-Chair,formerleader •SirChrisFox,formerChiefConstableof oftheLiberalDemocraticPartyandformer