Transcending the World's Decline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lhasa Jokhang – Is the World's Oldest Timber Frame Building in Tibet? André Alexander*

The Lhasa Jokhang – is the world's oldest timber frame building in Tibet? * André Alexander Abstract In questo articolo sono presentati i risultati di un’indagine condotta sul più antico tempio buddista del Tibet, il Lhasa Jokhang, fondato nel 639 (circa). L’edificio, nonostante l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List dell’UNESCO, ha subito diversi abusi a causa dei rifacimenti urbanistici degli ultimi anni. The Buddhist temple known to the Tibetans today as Lhasa Tsuklakhang, to the Chinese as Dajiao-si and to the English-speaking world as the Lhasa Jokhang, represents a key element in Tibetan history. Its foundation falls in the dynamic period of the first half of the seventh century AD that saw the consolidation of the Tibetan empire and the earliest documented formation of Tibetan culture and society, as expressed through the introduction of Buddhism, the creation of written script based on Indian scripts and the establishment of a law code. In the Tibetan cultural and religious tradition, the Jokhang temple's importance has been continuously celebrated soon after its foundation. The temple also gave name and raison d'etre to the city of Lhasa (“place of the Gods") The paper attempts to show that the seventh century core of the Lhasa Jokhang has survived virtually unaltered for 13 centuries. Furthermore, this core building assumes highly significant importance for the fact that it represents authentic pan-Indian temple construction technologies that have survived in Indian cultural regions only as archaeological remains or rock-carved copies. 1. Introduction – context of the archaeological research The research presented in this paper has been made possible under a cooperation between the Lhasa City Cultural Relics Bureau and the German NGO, Tibet Heritage Fund (THF). -

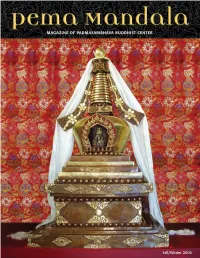

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner

4 Nights Incentive Programme Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner Country Name Lhasa, the heart and soul of Tibet, is a city of wonders. The visits to different sites in Lhasa would be an overwhelming experience. Potala Palace has been the focus of the travelers for centuries. It is the cardinal landmark and a structure of massive proportion. Similarly, Norbulingka is the summer palace of His Holiness Dalai Lama. Drepung Monastery is one of the world’s largest and most intact monasteries, Jokhang temple the heart of Tibet and Barkhor Market is the place to get the necessary resources for locals as well as souvenirs for tourists. At the end of this trip we visit the Samye Monastery, a place without which no journey to Tibet is complete. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 1 Arrive in Lhasa Country Name Day 1 o Morning After a warm welcome at Gonggar Airport (3570m) in Lhasa, transfer to the hotel. Distance (Airport to Lhasa): 62kms/ 32 miles Drive Time: 1 hour approx. Altitude: 3,490 m/ 11,450 ft. o Leisure for acclimatization Lhasa is a city of wonders that contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist religious sites and lies in a valley next to the Lhasa River. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 2 In Lhasa Country Name Day 2 o Morning: Set out to visit Sera and Drepung Monasteries Founded in 1419, Sera Monastery is one of the “great three” Gelukpa university monasteries in Tibet. 5km north of Lhasa, the Sera Monastery’s setting is one of the prettiest in Lhasa. The Drepung Monastery houses many cultural relics, making it more beautiful and giving it more historical significance. -

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: Meditation

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: meditation & yoga retreat – with cat & phil Eskdalemuir, Dumfriesshire, Scotland Kagyu Samye Ling - tibetan buddhist centre/kagyu tradition Thursday, 8th – Sunday, 11th August 2019 Cost: £350 tuition (includes donation to Kagyu Samye Ling) This is an additional way we have chosen to support the monastery & their ongoing charitable work. Accommodation to be booked directly with Samye Ling. Deposit: £200 to hold a space – (FULL CAPACITY – PREVIOUS YEARS) Balance due: 8th June (two months prior) – NO REFUNDS AFTER THIS DATE Payment methods: cash/cheque/bank transfer Cheques made out to: Catherine Alip-Douglas Bank transfer to: TSB – Bayswater Branch, 30-32 Westbourne Grove sort code: 309059, account number:14231860, Swift/BIC code: IBAN:GB49TSBS30905914231860 BIC: TSBSGB2AXXX The Retreat: 3 nights/4 days includes a tour of samye ling, daily yoga sessions (2- 2.5hours), lectures, meditation practice with Samye Ling’s sangha, a film screening of “AKONG” based on Akong Rinpoche, one of the founders of KSL and informal gatherings in an environment conducive to a proper ‘retreat’. As always, this retreat is also part of the Sangyé Yoga School's 2019 TT. There will be time for walks in the beautiful surroundings and reading books from their well-stocked and newly expanded gift shop. NOT INCLUDED: accommodation (many options depending on your budget) & travel. Kagyu Samye Ling provides the perfect environment to reconnect with nature, go deeper in your meditation practice, learn about the foundations of Tibetan Buddhism and the Kagyu lineage. It is a simple retreat for students who want to get to the heart of a practice and spend more time than usual in meditation sessions. -

AN Introduction to MUSIC to DELIGHT ALL the SAGES, the MEDICAL HISTORY of DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’

I AN iNTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’ STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of theft 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated framework ofInstructions for the Glorious field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ‘bubs or khog ‘bugs), this text — hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages — was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Truilcu Chokyi Wangchuk (1775-1837). Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 1 $th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related W” and 1 9th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for sharing a copy of the handwritten manuscript of Music to Delight All the Sages with me and for his encouragement and assistance of this work over its duration. This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. -

An Adventure in Tibet 18 April to May 2 , 2015

TIBETAN VILLAGE PROJECT AUSTRALIA INC. ABN: 98 504 209 907 PO BOX 417 BLACK ROCK VICTORIA, 3193 AUSTRALIA www.tvpaustralia.org.au An Adventure in Tibet 18 th April to May 2 nd , 2015. This itinerary is correct at the time of publishing, however, there are some situations that may change and we cannot guarantee that the itinerary as set out below. What we do promise, is an adventure that you will not forget. We do have a “Plan B” in case we cannot get to Lhasa, however, we work on the premise that we will get our permits for Lhasa. You will be meeting some lovely people, you will be made welcome in people’s homes and you will be travelling to remote places where few westerners have seen before. Saturday 18 th , April Arrive in Chengdu . You will be met by Don, the group leader, and transferred to the Traffic Inn which is our accommodation in Chengdu. Sunday 19 th , April After breakfast, we will visit the world famous Giant Panda Breeding Centre in Chengdu. The pandas are most active in the morning so you will have plenty of photo opportunities!! In the afternoon you may like to rest at the hotel or do a couple of hours of supply shopping. The hostel at the back of the Traffic Hotel has a small internet café if you wish to catch up 1 on some emails. We will have our trip orientation and welcome dinner tonight at a well-known Tibetan restaurant. Monday 20 th , April Today we fly from Chengdu to Kangding (flight is approximately 2 hrs duration) and then drive to Tagong . -

History of the Ngakpa Tradition

History of the Ngakpa Tradition The first Ngakpa centre The Ngakpa Community is was a branch of Samye originally called college and was called the 'Go kar Chang lo’ De Ngakpa 'Dud dul Ling'. which literally means There, people were 'The community with white trained in the subjects of dress and long hair' or more Literature,Translation, simply 'The group of white Sangha'. Astrology, Meteorology and especially Vajrayana studies and practice. Copyright © Ngak-Mang International 2006 History of the Ngakpa Tradition Tibetan regions and plateau Ngakpa dud dul ling In the 9th Century, Tri Ralpa Chan(866-?), the 3rd Tibetan Dharma King, became involved in the Ngakpa Tradition. Through his dedication and support the Ngakpa Tradition grew all over Tibet. Copyright © Ngak-Mang International 2006 Ngakpas in Different Schools Renouncing Ngakpa Tibetan Buddhism is divided into Kagyu school Naljorpa, 5 schools and each of them has Naljorma,Togtenpa. their own way of Ngakpas. Special Ngakpas Chod school Ngakpa, Chodpa. Family lineage Ngakpas Tibetan Indigenous Ngakpa Sakya school Ngakpa, Gongma. Bonpo school Ngakpa, Dransong. Monastic Ngakpas Most prevalent Ngakpa Gelug school Ngakpa, naljorpa, Nyingma school Ngakpa, Ngakmo, Kyimngak, Ge-nyen. Sumdan Dorje zinpa. Drongngak. Tertons and Rigzin. Copyright © Ngak-Mang International 2006 Women’s Equality Tibetan women are recognized as one of the largest contributors to the Ngakpa tradition. Ngakmo (yogini) such as Yeshe Tsogyal(777-837 A.D), Machin Labdron(1103-1201), Sera Khadroma(1899-1952) Chusep Jetsun(?-1951) Tare Lhamo(1938-2002) were highly respected practitioners and were an inspiration to First Tibetan Ngakmo- many Tibetan women. Yeshe Tsogyel Copyright © Ngak-Mang International 2006 Ngak-Mang Institute NMI was founded in 1999, in Xining, Qinghai, Amdo. -

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Sakya Chronicles 2016-2017 Remembering His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Dorje Chang (1929-2016) Welcome to Sakya Chronicles Dear Friends

Sakya Chronicles 2016-2017 Remembering His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Dorje Chang (1929-2016) Welcome to Sakya Chronicles Dear Friends, Th is issue of the Sakya Chronicles is dedicated to the memory of our beloved Head Lama, His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Dorje Chang, who tirelessly devoted himself to the preservation and sharing of the profound Buddha Dharma for all sentient beings. His life and parinirvana manifested the glory of fi lling divine space with infi nite compassion -- footsteps for us to follow... Yours in the Dharma, Adrienne Chan Executive Co-Director Sakya Monastery of Tibetan Buddhism 108 NW 83rd St., Seattle, WA 98117 206-789-2573, [email protected], www.sakya.org Table of Contents Khadro Sudhog Ceremony for H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Rinpoche .................................................................................................3 His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Sakya Enters Parinirvana ...............................................................................................................4 A Great Leader Passes on in Seattle ................................................................................................................................................6 Parinirvana of His Holiness .............................................................................................................................................................9 Cremation in India ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

1 My Literature My Teachings Have Become Available in Your World As

My Literature My teachings have become available in your world as my treasure writings have been discovered and translated. Here are a few English works. Autobiographies: Mother of Knowledge,1983 Lady of the Lotus-Born, 1999 The Life and Visions of Yeshe Tsogyal: The Autobiography of the Great Wisdom Queen, 2017 My Treasure Writings: The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava, 1978 The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava, 1999 Treasures from Juniper Ridge: The Profound Instructions of Padmasambhava to the Dakini Yeshe Tsogyal, 2008 Dakini Teachings: Padmasambhava’s Advice to Yeshe Tsogyal, 1999 From the Depths of the Heart: Advice from Padmasambhava, 2004 Secondary Literature on the Enlightened Feminine and my Emanations: Women of Wisdom, Tsultrim Allione, 2000 Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, Judith Simmer- Brown, 2001 Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chod, Sarah Harding, 2003 Women in Tibet, Janet Gyatso, 2005 Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, and the Art of the Self, Anne Carolyn Klein, 1995 When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet, Hildegard Diemberger, 2014 Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro, Sarah Jacoby, 2015 1 Love Letters from Golok: A Tantric Couple in Modern Tibet, Holly Gayley, 2017 Inseparable cross Lifetimes: The Lives and Love Letters of the Tibetan Visionaries Namtrul Rinpoche and Khandro Tare Lhamo, Holly Gayley, 2019 A Few Meditation Liturgies: Yumkha Dechen Gyalmo, Queen of Great Bliss from the Longchen Nyingthik, Heart- Essence of the Infinite Expanse, Jigme Lingpa Khandro Thukthik, Dakini Heart Essence, Collected Works of Dudjom, volume MA, pgs. -

Tibetan Schools of Buddhism

Tibetan schools of Buddhism December 18, 2018 Manifest pedagogy The various sub-schools of the prominent religions of India have been regularly asked as questions in prelims the best examples being the Sarasvativadins (Buddhism) and Sthanakavasis (Jainism) in the last couple of years. As the current events are revolving around the political aspects of Tibet its cultural aspects surely gain prominence. In news Kathok Getse Rinpoche, the seventh head of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism, has died The speculations of conflict between Karmapa Lama and Dalai lama Placing it in syllabus Indian Heritage and Culture Dimensions Buddhism history Buddhist philosophy Various schools of Buddhism Sthaviravadins Mahasangikas Hinayana Mahayana Vajrayana Neo-Buddhists and Ambedkar. Content Tibetan schools of Buddhism The Buddha didn’t write any of his teachings down; consequently, up to 18 different “schools” sprang up over the years to transmit and explain their interpretation of his teachings. Some of these schools included; Vajrayana (The thunderbolt vehicle) Is a yogic and magical school. Emphasis on realization of Sunyata (nothingness). Based on the need for an Enlightened Guru to show the path. Main deities were the Taras who were the female consorts of Bodhisattvas. Emphasis on Tantra- Mantra and Yantra (Magical symbol). The main mantra is OM-MANI-PADME-HUM. Sarvastivada – school influenced the evolution of Vajrayana sect. Buddhism first reached Tibet in the 7th century. By the 8th- century teachers such as Padmasambhava were traveling to Tibet to teach the dharma. The Tibetian schools of Buddhism were influenced by the prevailing medieval ethos of Tantricism, local tibetian beliefs and the teachings of Buddha. -

6 Days Tibet Historical Tour with Yarlung Valley and Hiking

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 6 days Tibet historical tour with Yarlung Valley and hiking https://windhorsetour.com/lhasa-tour/lhasa-samye-chimpu-hiking-tour Lhasa Tsedang Samye Trekking Lhasa Travel to the roof of the world to see its spectacular scenery and experience its unique culture first hand. Explore the regions ancient religious history by visiting key Tibetan monasteries in and around Lhasa. Type Private Duration 6 days Theme Culture and Heritage, Winter getaways Trip code TWT-TCH-01 Price From ¥ 3,700 per person Itinerary Day 01 : Arrival at Tibet- forbidden land of snow (3600m) At your arrival your Tibetan guide and driver will pick you up and transfer to the hotel in Lhasa, it is only 68km and two hrs from the airport, from 15km which take 20 minutes. Take rest to acclimatize and alleviate jetlag. Overnight at Lhasa. Day 02 : Lhasa city sightseeings (3600m) (B) Today is your first day of sightseeing on the high plateau, so we have purposely arranged only to visit Jokhang temple and Potala Palace. Jokhang temple is the most scared shrine in Tibet which was built in 7th century and located at the heart of old town in Lhasa, the circuit around it called Barkhor street, which is a good place to purchase souvenirs. Potala Palace is the worldwide known cardinal landmark of Tibet. The massive structure itself contains a small world within it. Mostly it is renowned as residence of the Dalai Lama lineages (Avalokiteshvara). Both of them are the focal points of pilgrims from entire Tibetan world, multitudinous pilgrims are circumambulating and prostrating in their strong faith.