Spring 2002 For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interpretation of the Structural Geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/26 An interpretation of the structural geology of the Franklin Mountains, Texas Earl M. P. Lovejoy, 1975, pp. 261-268 in: Las Cruces Country, Seager, W. R.; Clemons, R. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 26th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 376 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1975 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous Stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County Area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/21 Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F. E. Kottlowski, and A. K. Armstrong, 1970, pp. 33-44 in: Tyrone, Big Hatchet Mountain, Florida Mountains Region, Woodward, L. A.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 21st Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 176 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1970 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

By Douglas P. Klein with Plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein with plates by G.A. Abrams and P.L. Hill U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado Open-file Report 95-506 1995 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. The use of trade, product, or firm names in this papers is for descriptive purposes only, and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. STRUCTURE OF THE BASINS AND RANGES, SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO, AN INTERPRETATION OF SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTIONS by Douglas P. Klein CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1 DEEP SEISMIC CRUSTAL STUDIES .................................. 4 SEISMIC REFRACTION DATA ....................................... 7 RELIABILITY OF VELOCITY STRUCTURE ............................. 9 CHARACTER OF THE SEISMIC VELOCITY SECTION ..................... 13 DRILL HOLE DATA ............................................... 16 BASIN DEPOSITS AND BEDROCK STRUCTURE .......................... 20 Line 1 - Playas Valley ................................... 21 Cowboy Rim caldera .................................. 23 Valley floor ........................................ 24 Line 2 - San Luis Valley through the Alamo Hueco Mountains ....................................... 25 San Luis Valley ..................................... 26 San Luis and Whitewater Mountains ................... 26 Southern -

A Proposed Low Distortion Projection for the City of Las Cruces and Dona Ana County Scott Farnham, PE, PS City Surveyor, City of Las Cruces NM October 2020

A Proposed Low Distortion Projection for the City of Las Cruces and Dona Ana County Scott Farnham, PE, PS City Surveyor, City of Las Cruces NM October 2020 Introduction As part of the ongoing modernization of the U.S. National Spatial Reference System (NSRS), the National Geodetic Survey (NGS) will replace our horizontal and vertical datums (NAD83 and NAVD88) with new geometric datums assigned in the North American Terrestrial Reference Frame of 2022 (NATRF2022). The City of Las Cruces / Dona Ana County and the City of Albuquerque / Bernalillo County submitted proposals to NGS to incorporate Low Distortion Projections (LDP) as part of the New Mexico State Plane Coordinate Systems. Approval by NGS was obtained on June 17, 2019 for the proposed systems (see approval notice). Design of the LDP is the responsibility of the submitting agencies and must be submitted to NGS on or prior to March 31, 2021. Mark Marrujo1 with NMDOT is submitting final LDP design forms to NGS for the State of New Mexico. The City of Las Cruces (City) is designing a new Low Distortion Projection for Public Works Department, Engineering and Architecture projects to NGS criteria. To meet NGS LDP minimum size and shape criterion, the LDP area extends to Dona Ana County (County) boundary lines. This report presents design analysis and conclusions of the proposed City / County local NGS LDP system for stakeholders’ review prior to NGS final design submittal. NGS NM SPCS2022 Zones and Stakeholder Organizations NGS is designing new State Plane Coordinate Systems (SPCS2022) for New Mexico. The default SPCS2022 designs for the State are a statewide single zone and the three State Plane Zones: West, Central, and East. -

Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

-» Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico By R. A. BAILEY, R. L. SMITH, and C. S. ROSS CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY » GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1274-P New Stratigraphic names and revisions in nomenclature of upper Tertiary and , Quaternary volcanic rocks in the Jemez Mountains UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1969 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract.._..._________-...______.._-.._._____.. PI Introduction. -_-________.._.____-_------___-_______------_-_---_-_ 1 General relations._____-___________--_--___-__--_-___-----___---__. 2 Keres Group..__________________--------_-___-_------------_------ 2 Canovas Canyon Rhyolite..__-__-_---_________---___-____-_--__ 5 Paliza Canyon Formation.___-_________-__-_-__-__-_-_______--- 6 Bearhead Rhyolite-___________________________________________ 8 Cochiti Formation.._______________________________________________ 8 Polvadera Group..______________-__-_------________--_-______---__ 10 Lobato Basalt______________________________________________ 10 Tschicoma Formation_______-__-_-____---_-__-______-______-- 11 El Rechuelos Rhyolite--_____---------_--------------_-_------- 11 Puye Formation_________________------___________-_--______-.__- 12 Tewa Group__._...._.______........___._.___.____......___...__ 12 Bandelier Tuff.______________.______________... 13 Tsankawi Pumice Bed._____________________________________ 14 Valles Rhyolite______.__-___---_____________.________..__ 15 Deer Canyon Member.______-_____-__.____--_--___-__-____ 15 Redondo Creek Member.__________________________________ 15 Valle Grande Member____-__-_--___-___--_-____-___-._-.__ 16 Battleship Rock Member...______________________________ 17 El Cajete Member____..._____________________ 17 Banco Bonito Member.___-_--_---_-_----_---_----._____--- 18 References . -

Geothermal Hydrology of Valles Caldera and the Southwestern Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO By Frank W. Trainer, Robert J. Rogers, and Michael L. Sorey U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER Albuquerque, New Mexico 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 5338 Montgomery NE, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Albuquerque, NM 87109-1311 Information regarding research and data-collection programs of the U.S. Geological Survey is available on the Internet via the World Wide Web. You may connect to the Home Page for the New Mexico District Office using the URL: http://nm.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................ 2 Purpose and scope........................................................................................................................ -

Southwest Area 2015 Aviation Contacts and Communications Guide

Southwest Area 2015 Aviation Contacts and Communications Guide “Safety First” Printed on recycled paper. May 2015 Contents Dispatch Centers .................................................................... 3-4 Air-to-Ground Radio Frequencies Map .....................................5 Air-to-Air Radio Frequencies Map ............................................6 Tones and Frequencies ...............................................................7 New Mexico Frequencies Alamogordo Interagency Dispatch Center .................... 8-9 Albuquerque Interagency Dispatch Center ....................... 10-11 Silver City Interagency Dispatch Center .................. 12-13 Santa Fe Interagency Dispatch Center ...................... 14-15 Taos Interagency Dispatch Center ............................ 16-17 Arizona Frequencies Arizona Interagency Dispatch Center ....................... 18-19 Flagstaff Interagency Dispatch Center ...................... 20-21 Phoenix Interagency Dispatch Center ....................... 22-23 Prescott Interagency Dispatch Center ....................... 24-27 Show Low Interagency Dispatch Center .................. 28-31 Tucson Interagency Dispatch Center ........................ 32-33 Williams Interagency Dispatch Center ..................... 34-35 Southwest Aviation Phone Contact List R3 Regional Office .........................................................36 Bureau of Indian Affairs .................................................37 Bureau of Land Management..........................................37 National -

Geologic Controls on Ground-Water Flow in the Mimbres Basin, Southwestern New Mexico Finch, Steven T., Jr

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/59 Geologic controls on ground-water flow in the Mimbres Basin, southwestern New Mexico Finch, Steven T., Jr. McCoy, Annie and Erwin Melis, 2008, pp. 189-198 in: Geology of the Gila Wilderness-Silver City area, Mack, Greg, Witcher, James, Lueth, Virgil W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 59th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 210 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2008 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

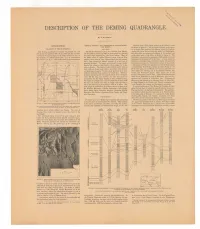

Description of the Deming Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE DEMING QUADRANGLE, By N. H. Darton. INTRODUCTION. GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHWESTERN Paleozoic rocks. The general relations of the Paleozoic rocks NEW MEXICO. are shown in figure 3. 2 All the earlier Paleozoic rocks appear RELATIONS OF THE QUADRANGLE. STRUCTURE. to be absent from northern New Mexico, where the Pennsyl- The Deming quadrangle is bounded by parallels 32° and The Rocky Mountains extend into northern New Mexico, vanian beds lie on the pre-Cambrian rocks, but Mississippian 32° 30' and by meridians 107° 30' and 108° and thus includes but the southern part of the State is characterized by detached and older rocks are extensively developed in the southern and one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's surface, an area, in mountain ridges separated by wide desert bolsons. Many of southwestern parts of the State, as shown in figure 3. The that latitude, of 1,008.69 square miles. It is in southwestern the ridges consist of uplifted Paleozoic strata lying on older Cambrian is represented by sandstone, which appears to extend New Mexico (see fig. 1), a few miles north of the international granites, but in some of them Mesozoic strata also are exposed, throughout the southern half of the State. At some places the and a large amount of volcanic material of several ages is sandstone has yielded Upper Cambrian fossils, and glauconite 109° 108° 107" generally included. The strata are deformed to some extent. in disseminated grains is a characteristic feature in many beds. Some of the ridges are fault blocks; others appear to be due Limestones of Ordovician age outcrop in all the larger ranges solely to flexure. -

Southwest NM Publication List

Southwest New Mexico Publication Inventory Draft Source of Document/Search Purchase Topic Category Keywords County Title Author Date Publication/Journal/Publisher Type of Document Method Price Geology 1 Geology geology, seismic Southwestern NM Six regionally extensive upper-crustal Ackermann, H.D., L.W. 1994 U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 94- Electronic file USGS publication search refraction profiles, seismic refraction profiles in Southwest New Pankratz, D.P. Klein 695 (DJVU) http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/usgspubs/ southwestern New Mexico ofr/ofr94695 Mexico, 2 Geology Geology, Southwestern NM Magmatism and metamorphism at 1.46 Ga in Amato, J.M., A.O. 2008 In New Mexico Geological Society Fall Field Paper in Book http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/g $45.00 magmatism, the Burro Mountains, southwestern New Boullion, and A.E. Conference Guidebook - 59, Geology of the Gila uidebooks/59/ metamorphism, Mexico Sanders Wilderness-Silver City area, 107-116. Burro Mountains, southwestern New Mexico 3 Geology Geology, mineral Catron County Geology and mineral resources of York Anderson, O.J. 1986 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Electronic file (PDF) NMBGMR search $10.00 for resources, York Ranch SE quadrangle, Cibola and Catron Resources Open File Report 220A, 22 pages. <http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publicatio CD Ranch, Fence Counties, New Mexico ns/openfile/details.cfml?Volume=2 Lake, Catron, 20A> Cibola 4 Geology Geology, Zuni Salt Catron County Geology of the Zuni Salt Lake 7 1/2 Minute Anderson, O.J. 1994 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Geologic Setting, Hydrology, and Geochemistry of the Hueco Tanks Geothermal Area, Texas and New Mexico

Geological Circular 81-1 APreliminaryAssessmentoftheGeologicSetting,Hydrology,andGeochemistyoftheHuecoTanksGeothermalArea,TexasandNewMexico Christopher D.Henry and James K.Gluck jointly published by Bureau of Economic Geology The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 W. L.Fisher,Director and Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council Executive Office Building 411 West 13th Street, Suite 800 Austin, Texas 78701 Milton L. Holloway, Executive Director prime funding provided by Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council throughInteragency Cooperation Contract No.IAC(80-81)-0899 1981 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Regional geologic setting 2 Origin and locationof geothermal waters 5 Hot wells 5 Source of heat and ground-water flow paths 5 Faults in geothermal area 9 Implications of geophysical data 15 Hydrology 16 Data availability 16 Water-table elevation 17 Substrate permeability 19 Geochemistry 22 Geothermometry 27 Summary 32 Acknowledgments 32 References 33 Appendix A. Well data 35 Appendix B. Chemical analyses Wl Appendix C. Well designations WJ Figures 1. Tectonic map of Hueco Bolson near El Paso, Texas 3 2. Wells in Hueco Tanks geothermal area 6 3. Measured andreported temperatures ( C) of thermal and nonthermal wells 7 4. Depth to bedrock, absolute elevation of bedrock, and inferred normal faults . 10 5. Generalized west-east cross sections in Hueco Tanks geothermal area . .11 6. Depth to water table, absolute elevation of water table, and water- table elevation contours 18 111 7. Percentages of gravel, sand, clay, and bedrock from driller's logs 21 8. Trilinear diagram of thermal and nonthermal waters 24 9. Total dissolved solids and chloride concentrations 25 Tables 1. Saturation indices 28 2.