Early Yom Tov/Seder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 71: the Core of Joy

Daf Ditty Pesachim 71: The Core of Joy 1 at the time of rejoicing, on the Festival itself, and if it was slaughtered on the fourteenth it is not. The mitzva to bring a Festival peace-offering is also not fulfilled, for it is something that is an obligation, as everyone is obligated to bring this offering, and the principle is that anything that is an obligation must come only from that which is unconsecrated, meaning that one cannot bring an obligatory offering from an animal that has already been consecrated for another purpose. The Gemara proposes: Let us say that a baraita supports him. The verse states: Seven days shalt thou keep a feast unto the LORD thy God 15 וט ְתּמתיﬠִשׁב ָי,םחַָ ֹגִ FֱהDיוהַלהא ֶ,יָ ֶ,יָ FֱהDיוהַלהא in the place which the LORD shall choose; because the LORD קשׁ,ַבּאםמּ ֲֶָרוֹ - ְיָהוה: ְִיַבחר יִכּ Fבי ְהְכהויר ְֶָָ ְהְכהויר Fבי יִכּ thy God shall bless thee in all thine increase, and in all the work ,בֶּיFֱאDה לתְּכ בFְָתוּאבֹ למְכְוּ הֲַשׂﬠֹ ֵי ,ֶיFָד ,ֶיFָד ֵי הֲַשׂﬠֹ למְכְוּ בFְָתוּאבֹ לתְּכ ,בֶּיFֱאDה .of thy hands, and thou shalt be altogether joyful ֵָשַׂמ.ח ְוִָייהָ,תַאT ֵָשַׂמ.ח Deut 16:15 “Seven days shall you celebrate to the Lord your God in the place that the Lord shall choose, for the Lord your God shall bless you in all your produce and in all the work of your hands, and you shall be but joyous” This verse seems superfluous, as it was already stated in the previous verse: “And you shall rejoice in your Festival.” The baraita expounds: “And you shall be but joyous” comes to include the last night of the Festival. -

Shabbat Chol Hamoed Sukkot September 29-October 5, 2018

Shabbat Chol HaMoed Sukkot September 29-October 5, 2018 — 20-26 Tishrei 5779 Torah reading — Exodus 33:12-34:26, pg 504, Baal Koreh — Jerry Rotenberg Haftarah— Ezekiel 38:18-39:16 pg 1243 — Rabbi Yaakov Chaitovsky Taste of Torah parashah shiur with Essie Fleischman at 10:00 am in the Gallery Prayer Pearls: Connecting Tefilah with Reb Noam Horowitz at 11:00 am in the Gallery Rabbi Yaakov Chaitovsky Cantor Martin Goldstein Ilene Rosen—Executive Director Cantor Emeritus Joel Lichterman Jeff Kline— Shul President Cantor Emeritus Zachary Kutner Hoshanah Rabah, Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah September 30-October 2, 2018 — 21-23 Tishrei 5779 Simchat Torah Hakafot — Monday, October 1 Regular hakafot will follow Maariv in the Chapel & women are invited to join DAT-Minyan for women’s hakafot following Maariv at 5:45 pm in the Gallery Roll the Scroll, Young Family hakafot & dinner at 5:30 pm in the Social Hall Monday— October 1 Wednesday— October 3 Service Times Shemini Atzeret—Yizkor Daf Yomi 5:45am Saturday— September 29 Daf Yomi 8:15 am Shacharit, Chapel 6:45 am Daf Yomi 8:00 am Shacharit, Sanctuary 9:00 am Rabbi’s Class 7:30 am Shacharit, Sanctuary 9:00 am Shacharit, Chapel 9:15 am Mincha/Maariv, Chapel 6:15 pm Shacharit, Chapel 9:15 am Yizkor, Sanct. 10:15am Thursday— October 4 Mincha, Chapel 6:15 pm Mincha/Maariv 5:20 pm Daf Yomi 5:30 am Havdalah 7:28 pm Adult Hakafot at 6:45pm Shacharit, Chapel 6:30 am Sunday— September 30 Candle Lighting 7:24pm Ellyn Hutt Class 11:00 am Hoshanah Rabah Tuesday— October 2 Mincha/Maariv 6:15 pm Daf Yomi 7:00 am Simchat Torah Friday— October 5 Shacharit, Chapel 8:00 am Daf Yomi 8:00 am Daf Yomi 5:45 am Candle Lighting 6:24 pm Shacharit, Chapel 9:00 am Shacharit, Chapel 6:45 am Mincha/Maariv 6:30 pm Adult Hakafot at 9:00am Mincha 6:15 pm Mincha/Maariv 6:30 pm Candle Lighting 6:16 pm שבת שלום ומבורך! Havdallah 7:23 pm On Shabbat and Shemini Atzeret, please join us for Kiddush in the Sukkah sponsored by BMH-BJ. -

Modern Approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London

09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the View Online Talmud: Sacha Stern Albeck, Chanoch, Mavo La-Talmudim (Tel-Aviv: Devir, 1969) Alexander, Elizabeth Shanks, Transmitting Mishnah: The Shaping Influence of Oral Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) Amit, Aaron, Makom She-Nahagu: Pesahim Perek 4 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2009), Talmud ha-igud Ba’adani, Netanel, Hayu Bodkin: Sanhedrin Perek 5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2012), Talmud ha-igud Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal, Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) Benovitz, Moshe, Lulav va-Aravah ve-Hahalil: Sukkah Perek 4-5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2013), Talmud ha-igud ———, Me-Ematai Korin et Shema: Berakhot Perek 1 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2006), Talmud ha-igud Brody, Robert, Mishnah and Tosefta Studies, First edition, July 2014 (Jerusalem: The Hebrew university, Magnes press, 2014) ———, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, Paperback ed., with a new preface and an updated bibliography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) Carmy, Shalom, Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations (Northvale, N.J.: J. Aronson, 1996), The Orthodox Forum series Chernick, Michael L., Essential Papers on the Talmud (New York: New York University Press, 1994), Essential papers on Jewish studies Daṿid Halivni, Meḳorot U-Masorot (Nashim), ha-Mahadurah ha-sheniyah (Ṭoronṭo, Ḳanadah: Hotsaʼat Otsarenu) ———, Meḳorot U-Masorot: Seder Moʼed (Yerushalayim: Bet ha-Midrash le-Rabanim be-Ameriḳah be-siṿuʻa Keren Moshe (Gusṭaṿ) Ṿortsṿayler, 735) ‘dTorah.com’ <http://dtorah.com/> 1/5 09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London Epstein, J. -

Passover Seder Illustration Regina Gruss Charitable and Educational Foundation, Inc

Materials needed: A Seder is a meal that takes place during the • Paper Jewish holiday of Passover and involves the • Colored pencils/crayons/markers retelling of a story in the Book of Exodus, part of the Hebrew Bible. The story describes how the Israelites escaped from a life of slavery in ancient Egypt. Family and friends read from a book called a Haggadah. They sing songs together and eat special foods. Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, Seder (The Passover Meal) (Der Oster-Abend), 1867. Nicole Eisenman, Seder, 2010. Oil on canvas. The Jewish Museum, New York. Oil on paper on canvas. The Jewish Museum, New York. Gift of the Oscar and Purchase: Lore Ross Bequest; Milton and Miriam Handler Endowment Fund; PASSOVER FAMILY ART ACTIVITIES ART FAMILY PASSOVER Passover Seder Illustration Regina Gruss Charitable and Educational Foundation, Inc. and Fine Arts Acquisitions Committee Fund. Artwork © Nicole Eisenman. Look together at the images from the Jewish If you have been to a Seder or special family Museum’s collection of family Passover scenes. meal, how would you draw that memory? How are these paintings the same, and how are Talk together about the foods you would they different? have on your table. Whom would you invite? What would the Seder plate and other details look like? Using a sheet of paper and colored pencils, markers, or crayons, draw a memory of a Seder or a special family meal you have shared together. Materials Needed: Examine together two examples depicting • Scissors items for a Seder plate, from the Jewish Museum’s collection. Notice the differences • Glue in design and arrangement of the ceremonial • Colored paper, magazines, newspapers foods. -

How to Passover the Soulful Meaning, How to Seder, History, Customs, Blessings, Schedules and How to Celebrate

Celebration!13 – 22 Nissan, 5770 / March 28 – April 6, 2010 How to pAssover the soulful meaning, how to seder, history, customs, blessings, schedules and how to celebrate. physically free, but mentally enslaved – not being able to see or consider beyond himself and his present Celebration! Pesach 5770 / 2010 Some needs. Right at the outset of g-d’s message of freedom, 3 REBBe’s MessAGe he conveyed to the Jewish People that not only will Celebrate Your Freedom they be relieved of their back-breaking slave labor, 3 Join our seDer suffering and torture, but he immediately announced that he will grant them “a land flowing with milk and 4 FREEDoM, FAItH, AND PassoverThoughts honey” – a state of mind completely unimaginable NAtIoNHOOD to them at the time. 5 THe seDer Dear virgin Islands Jewry, • • • The practical how, what and the Freedom is the most valued aspect of the human race. For the Rebbe, Rabbi menachem m. Schneerson, meaning of items on the seder plate Slavery, the antithesis of freedom, on the other hand, oBm – whose birthday is on the 11th day of the 7 PASSOVER CHeCKLIst is the most abhorring idea of a free-thinking society. month of Nissan, four days before the holiday of But what’s wrong with slavery? Is it just because Passover – the idea of absolute personal freedom 8 SOULFuL seDer you are forced to do things against your will? Is it was one of the hallmarks of his leadership and Join us as we perform the Seder; as because you are subject to torture, or is it because you inspiration to his followers. -

Page 1 482 – Jalkut Schimoni Zwölfprophetenbuch 10 Abkürzungen Anm

482 Jalkut Schimoni Zwölfprophetenbuch 10 Abkürzungen Anm. O Anmerkung Midr. O Midrasch Aufl. O Auflage Ms. O Manuskript Bd. O Band MT O Masoretischer Text Bde. O Bände Ndr. O Neudruck / Nachdruck BH O Biblia Hebraica o.A. O ohne Angaben hebr. O hebräisch R. O Rabbi hg. O herausgegeben von S. O Seite LXX O Septuaginta Vgl. O Vergleiche Midraschim ARN A O Abot de Rabbi Natan, Version A ARN B O Abot de Rabbi Natan, Version B BhM O Bet ha-Midrasch (Midrasch Jona) ExR O Exodus, Schemot Rabba CantR O Canticum, Schir ha-Schirim, Hoheslied Rabba DtnR O Deuteronomium Rabba, Deverim Rabba GenR O Genesis, Bereschit Rabba LevR O Leviticus, Wajiqra Rabba Mek O Mekhilta de R. Jischmael MidrPs O Midrasch Psalmen MidrSam O Midrasch Samuel NumR O Numeri, Bemidbar Rabba PAB Est O Panim Acherot B zu Ester par. O Parascha per. O Pereq pet. O Peticha PR O Pesiqta Rabbati PRE O Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer PRK O Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana RutR O Rut Rabba SDtn O Sifre Deuteronomium, Devarim SNum O Sifre Numeri, Bemidbar SOR O Seder Olam Rabba Tan O Tanchuma, Ausgabe Warschau Open Access. © 2020 Farina Marx, publiziert von De Gruyter. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Lizenz. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110675382-010 Abkürzungen 483 TanB O Tanchuma, Ausgabe Buber ThrR O Threni, Klagelied, Echa Rabba Traktatnamen von Mischna, Tosefta, Talmudim b O Babylonischer Talmud t O Tosefta j O Jerusalemer Talmud Meg O Megilla AZ O Aboda Zara Men O Menachot BB O Baba Batra MQ O Moet Qatan Bek O Bekhorot Naz O Nazir Ber O Berakhot Ned O Nedarim BM O Baba Metsia Nid O Nidda BQ O Baba Qamma Pes O Pessachim Chag O Chagiga Qid O Qidduschin Chul O Chulin RH O Rosch ha-Schana Er O Erubin Sanh O Sanhedrin Git O Gittin Schab O Schabbat Jeb O Jebamot Schebu O Schebuot Ker O Keritot Suk O Sukka Ket O Ketubbot Taan O Taanit Mak O Makkot Zeb O Zebachim . -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

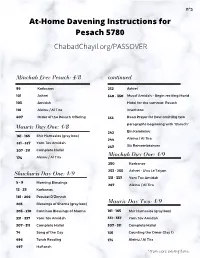

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

From Purim to Pesach and Back

RABBI’S MESSAGE From Purim to Pesach and Back The Hebrew calendar gives us a double blessing in the months of Adar and Nissan, with the holidays of Purim and Passover coming back-to-back. These celebrations are very different from each other, and yet the progression of one to the other on the calendar can give interesting ideas to explore. Both deal with bitter enemies and the possibility of genocidal extinction. The Purim villain, Haman, manipulates the Persian king into decreeing legalized murder of the Jewish people. Haman’s plan fails and the Jews retaliate. The Passover villain, Pharaoh, also threatens extinction by murdering Jewish baby boys at birth. This plan also fails, and the Israelites are redeemed by G-D’s “mighty hand and outstretched arm” to escape into the wilderness and eventually the Promised Land. From the 15th of Adar to the 15th of Nissan, the score is: Jews 2, Evil 0. Yes, both Purim and Pesach fulfill the traditional theme about Jewish holidays: “They tried to kill us. We survived. Let’s eat.” The survival elements and food are certainly part of our contemporary celebrations for both holidays. The threats occur differently, and so do our observances. While Passover precedes Purim chronologically, Purim precedes Passover on the calendar. I’ve often considered the various ways these two springtime festivals differ as ways to look at the growth of our people. In the Book of Esther, the name of God is not mentioned. In the traditional Passover Haggadah, the name of Moses is not mentioned. We are taught that Moses’ name was left out of the Haggadah for fear of deifying Moses.