Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Make Claims About Or Even Adequately Understand the "True Nature" of Organizations Or Leadership Is a Monumental Task

BooK REvrnw: HERE CoMES EVERYBODY: THE PowER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS (Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008. Hardback, $25.95] -CHRIS FRANCOVICH GONZAGA UNIVERSITY To make claims about or even adequately understand the "true nature" of organizations or leadership is a monumental task. To peer into the nature of the future of these complex phenomena is an even more daunting project. In this book, however, I think we have both a plausible interpretation of organ ization ( and by implication leadership) and a rare glimpse into what we are becoming by virtue of our information technology. We live in a complex, dynamic, and contingent environment whose very nature makes attributing cause and effect, meaning, or even useful generalizations very difficult. It is probably not too much to say that historically the ability to both access and frame information was held by the relatively few in a system and structure whose evolution is, in its own right, a compelling story. Clay Shirky is in the enviable position of inhabiting the domain of the technological elite, as well as being a participant and a pioneer in the social revolution that is occurring partly because of the technologies and tools invented by that elite. As information, communication, and organization have grown in scale, many of our scientific, administrative, and "leader-like" responses unfortu nately have remained the same. We find an analogous lack of appropriate response in many followers as evidenced by large group effects manifested through, for example, the response to advertising. However, even that herd like consumer behavior seems to be changing. Markets in every domain are fragmenting. -

Proceedings of the 46Th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Hu- Man Language Technologies, Pages 9–12

Coling 2010 23rd International Conference on Computational Linguistics Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on The People’s Web Meets NLP: Collaboratively Constructed Semantic Resources Produced by Chinese Information Processing Society of China All rights reserved for Coling 2010 CD production. To order the CD of Coling 2010 and its Workshop Proceedings, please contact: Chinese Information Processing Society of China No.4, Southern Fourth Street Haidian District, Beijing, 100190 China Tel: +86-010-62562916 Fax: +86-010-62562916 [email protected] ii Introduction This volume contains papers accepted for presentation at the 2nd Workshop on Collaboratively Constructed Semantic Resources that took place on August 28, 2010, as part of the Coling 2010 conference in Beijing. Being the second workshop on this topic, we were able to build on the success of the previous workshop on this topic held as part of ACL-IJCNLP 2009. In many works, collaboratively constructed semantic resources have been used to overcome the knowledge acquisition bottleneck and coverage problems pertinent to conventional lexical semantic resources. The greatest popularity in this respect can so far certainly be attributed to Wikipedia. However, other resources, such as folksonomies or the multilingual collaboratively constructed dictionary Wiktionary, have also shown great potential. Thus, the scope of the workshop deliberately includes any collaboratively constructed resource, not only Wikipedia. Effective deployment of such resources to enhance Natural Language Processing introduces a pressing need to address a set of fundamental challenges, e.g. the interoperability with existing resources, or the quality of the extracted lexical semantic knowledge. Interoperability between resources is crucial as no single resource provides perfect coverage. -

Cyber-Synchronicity: the Concurrence of the Virtual

Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material via Text-Based Virtual Reality A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jeffrey S. Smith March 2010 © 2010 Jeffrey S. Smith. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material Via Text-Based Virtual Reality by JEFFREY S. SMITH has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Joseph W. Slade III Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT SMITH, JEFFREY S., Ph.D., March 2010, Mass Communication Cyber-Synchronicity: The Concurrence of the Virtual and the Material Via Text-Based Virtual Reality (384 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Joseph W. Slade III This dissertation investigates the experiences of participants in a text-based virtual reality known as a Multi-User Domain, or MUD. Through in-depth electronic interviews, staff members and players of Aurealan Realms MUD were queried regarding the impact of their participation in the MUD on their perceived sense of self, community, and culture. Second, the interviews were subjected to a qualitative thematic analysis through which the nature of the participant’s phenomenological lived experience is explored with a specific eye toward any significant over or interconnection between each participant’s virtual and material experiences. An extended analysis of the experiences of respondents, combined with supporting material from other academic investigators, provides a map with which to chart the synchronous and synonymous relationship between a participant’s perceived sense of material identity, community, and culture, and her perceived sense of virtual identity, community, and culture. -

Using Wikipedia to Strengthen Research and Critical Thinking Skills

From Audience to Authorship to Authority: Using Wikipedia to Strengthen Research and Critical Thinking Skills Michele Van Hoeck and Debra Hoffmann This paper looks at Wikipedia’s effectiveness as a pedagogical tool to encourage students to think critical- ly about notions of audience, authorship and authority, and also Wikipedia’s impact on student research persistence. Two case studies are presented in which Wikipedia was used as the platform for assignments in 1) a two-unit freshman information literacy course at California State University (CSU), Maritime (Cal Maritime), and 2) in two three-unit, cross-listed upper-division courses at CSU Channel Islands (CI). At Cal Maritime, the course culminated with students significantly expanding a Wikipedia article. At CI, one course used Wikipedia to explore issues of authority and expertise; the other course used Wikipedia to think critically about notions of authorship and audience. Cal Maritime data on student attitudes, re- search practices such as interlibrary loan borrowing, and student citations suggest the Wikipedia plat- form had, overall, a positive impact on research persistence. Finally, the authors discuss lessons learned from initial use of Wikipedia in the classroom and opportunities for instruction librarians to incorporate Wikipedia into information literacy instruction outside of a credit-bearing course. Introduction and critical thinking skills as editors and creators of Information Literacy instruction often focuses on content. We take a case study approach in presenting cautioning students regarding the use of Wikipedia experiences on two California State University cam- as a credible source for their research, as authors of puses in which Wikipedia was used as the platform Wikipedia articles are often anonymous, and edit- for assignments in credit-bearing information literacy ing Wikipedia does not require proof of expertise. -

Program Statistics

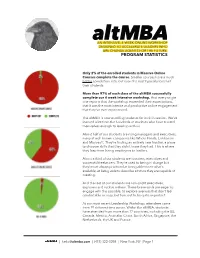

AN INTENSIVE, 4-WEEK ONLINE WORKSHOP DESIGNED TO ACCELERATE LEADERS WHO ARE CHANGE AGENTS FOR THE FUTURE. PROGRAM STATISTICS Only 2% of the enrolled students in Massive Online Courses complete the course. Smaller courses have a much better completion rate, but even the best typically lose half their students. More than 97% of each class of the altMBA successfully complete our 4 week intensive workshop. And every single one reports that the workshop exceeded their expectations, that it was the most intense and productive online engagement that they’ve ever experienced. The altMBA is now enrolling students for its fifth session. We’ve learned a lot from the hundreds of students who have trusted themselves enough to level up with us. About half of our students are rising managers and executives, many at well-known companies like Whole Foods, Lululemon and Microsoft. They’re finding an entirely new frontier, a place to discover skills that they didn’t know they had. This is where they leap from being employees to leaders. About a third of our students are founders, executives and successful freelancers. They’re used to being in charge but they’re not always practiced at being able to see what’s available, at being able to describe a future they are capable of creating. And the rest of our students are non-profit executives, explorers and ruckus makers. These brave souls are eager to engage with the possible, to explore avenues that don’t feel comfortable or easy, but turn out to be quite important. At our most recent Leadership Workshop, attendees came from 19 different time zones. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

The Broadcast Flag: Compatible with Copyright Law & Incompatible with Digital Media Consumers

607 THE BROADCAST FLAG: COMPATIBLE WITH COPYRIGHT LAW & INCOMPATIBLE WITH DIGITAL MEDIA CONSUMERS ANDREW W. BAGLEY* & JUSTIN S. BROWN** I. INTRODUCTION Is it illegal to make a high-quality recording of your favorite TV show using your Sony digital video recorder with your Panasonic TV, which you then edit on your Dell computer for use on your Apple iPod? Of course it’s legal, but is it possible to use devices from multiple brands together to accomplish your digital media goal? Yes, well, at least for now. What if the scenario involved high-definition television (“HDTV”) devices? Would the answers be as clear? Not as long as digital-content protection schemes like the Broadcast Flag are implemented. Digital media and Internet connectivity have revolutionized consumer entertainment experiences by offering high-quality portable content.1 Yet these attractive formats also are fueling a copyright infringement onslaught through a proliferation of unauthorized Internet piracy via peer-to-peer (“P2P”) networks.2 As a result, lawmakers,3 administrative agencies,4 and courts5 are confronted * Candidate for J.D., University of Miami School of Law, 2009; M.A. Mass Communication, University of Florida, 2006; B.A. Political Science, University of Florida, 2005; B.S. Public Relations, University of Florida, 2005 ** Assistant Professor of Telecommunication, University of Florida; Ph.D. Mass Communica- tions, The Pennsylvania State University, 2001 1 Andrew Keen, Web 2.0: The Second Generation of the Internet has Arrived. It's Worse Than You Think, WEEKLY STANDARD, Feb. 13, 2006, http://www.weeklystandard.com/ Con- tent/Public/Articles/000/000/006/714fjczq.asp (last visited Jan. -

Healthcare Blogging-A Review S Sethi

The Internet Journal of Radiology ISPUB.COM Volume 10 Number 2 Healthcare Blogging-A review S Sethi Citation S Sethi. Healthcare Blogging-A review. The Internet Journal of Radiology. 2008 Volume 10 Number 2. Abstract The Internet is changing medicine and web 2.0 is the current buzz word in the world wide web dictionary. According to Dean Giustini in British Medical Journal, web 2.0 means “the web as platform” and “architecture of participation”. It is the web or internet information which is created by the users themselves. Web 2.0 is primarily about the benefits of easy to use and free internet software. For example, blogs and wikis facilitate participation and conversations across a vast geographical expanse. Information pushing devices, like RSS feeds, permit continuous instant alerting to the latest ideas in medicine. Multimedia tools like podcasts and videocasts are increasingly popular in medical schools and medical journals. Recently, there has been no escaping the mention of blogs in the media. Blogging has emerged as a social phenomenon, which has impacted politics, business, and communication. Medical field or healthcare is also not immune to this global phenomenon. Hence this chapter will deal with this phenomenon of blogging, with emphasis on what is a blog, historical significance, various software platforms available, blogging for a physician, pros and cons of blogging in healthcare, examples from popular healthcare blogs and prediction for future trends. This chapter will familiarize the reader about healthcare blogs and their impact on healthcare. INTRODUCTION participating in these small communities with fellow A blog or weblog (derived from web+log) is a web based ‘‘techies.’‘ Because of the skills and understanding required publication consisting primarily of periodic articles to create blogs, they were not nearly as widespread as they (normally, but not always, in reverse chronological order). -

Crowdsourcing Metadata for Library and Museum Collections Using a Taxonomy of Flickr User Behavior

CROWDSOURCING METADATA FOR LIBRARY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS USING A TAXONOMY OF FLICKR USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Evan Fay Earle January 2014 © 2014 Evan Fay Earle ABSTRACT Library and museum staff members are faced with having to create descriptions for large numbers of items found within collections. Immense collections and a shortage of staff time prevent the description of collections using metadata at the item level. Large collections of photographs may contain great scholarly and research value, but this information may only be found if items are described in detail. Without detailed descriptions, the items are much harder to find using standard web search techniques, which have become the norm for searching library and museum collection catalogs. To assist with metadata creation, institutions can attempt to reach out to the public and crowdsource descriptions. An example of crowdsourced description generation is the website, Flickr, where the entire user community can comment and add metadata information in the forms of tags to other users’ images. This paper discusses some of the problems with metadata creation and provides insight on ways in which crowdsourcing can benefit institutions. Through an analysis of tags and comments found on Flickr, behaviors are categorized to show a taxonomy of users. This information is used in conjunction with survey data in an effort to show if certain types of users have characteristics that are most beneficial to enhancing metadata in existing library and museum collections. -

Liminality and Communitas in Social Media: the Case of Twitter Jana Herwig, M.A., [email protected] Dept

Liminality and Communitas in Social Media: The Case of Twitter Jana Herwig, M.A., [email protected] Dept. of Theatre, Film and Media Studies, University of Vienna 1. Introduction “What’s the most amazing thing you’ve ever found?” Mac (Peter Riegert) asks Ben, the beachcomber (Fulton Mackay), in the 1983 film Local Hero. ”Impossible to say,” Ben replies. “There’s something amazing every two or three weeks.” Substitute minutes for weeks, and you have Twitter. On a good day, something amazing washes up every two or three minutes. On a bad one, you irritably wonder why all these idiots are wasting your time with their stupid babble and wish they would go somewhere else. Then you remember: there’s a simple solution, and it’s to go offline. Never works. The second part of this quote has been altered: Instead of “Twitter”, the original text referred to “the Net“, and instead of suggesting to “go offline”, author Wendy M. Grossman in her 1997 (free and online) publication net.wars suggested to “unplug your modem”. Rereading net.wars, I noticed a striking similarity between Grossman’s description of the social experience of information sharing in the late Usenet era and the form of exchanges that can currently be observed on micro-blogging platform Twitter. Furthermore, many challenges such as Twitter Spam or ‘Gain more followers’ re-tweets (see section 5) that have emerged in the context of Twitter’s gradual ‘going mainstream’, commonly held to have begun in fall 2008, are reminiscent of the phenomenon of ‘Eternal September’ first witnessed on Usenet which Grossman reports. -

Usenet News HOWTO

Usenet News HOWTO Shuvam Misra (usenet at starcomsoftware dot com) Revision History Revision 2.1 2002−08−20 Revised by: sm New sections on Security and Software History, lots of other small additions and cleanup Revision 2.0 2002−07−30 Revised by: sm Rewritten by new authors at Starcom Software Revision 1.4 1995−11−29 Revised by: vs Original document; authored by Vince Skahan. Usenet News HOWTO Table of Contents 1. What is the Usenet?........................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Discussion groups.............................................................................................................................1 1.2. How it works, loosely speaking........................................................................................................1 1.3. About sizes, volumes, and so on.......................................................................................................2 2. Principles of Operation...................................................................................................................................4 2.1. Newsgroups and articles...................................................................................................................4 2.2. Of readers and servers.......................................................................................................................6 2.3. Newsfeeds.........................................................................................................................................6 -

Sending Newsgroup and Instant Messages

7.1 LESSON 7 Sending Newsgroup and Instant Messages After completing this lesson, you will be able to: Send and receive newsgroup messages Create and send instant messages Microsoft Outlook offers some alternatives to communicating via e-mail. With instant messages, you can connect with a client who is also using instant messaging to ask a simple question and get the answer immediately. On the other hand, Newsgroups allow you to communicate with a larger audience. When considering the purchase of a new graphics program, for example, you can solicit advice and recommendations by posting a message to a newsgroup for people interested in graphics. You don’t need any practice files to work through the exercises in this lesson. Sending and Receiving Newsgroup Messages A newsgroup is a collection of messages related to a particular topic that are posted by individuals to a news server . Newsgroups are generally focused on discussion of a particular topic, like a sports team, a hobby, or a type of software. Anyone with access to the group can post to the group and read all posted messages. Some newsgroups have a moderator who monitors their use, but most newsgroups are not overseen in this way. A newsgroup can be private, such as an internal company newsgroup, but there are newsgroups open to the public for practically every topic. You gain access to newsgroups through a news server maintained either on your organization’s network or by your Internet service provider (ISP). You use a newsreader program to download, read, and reply to news messages.