1 Bill Minor 2/15/12 Jackson, Mississippi Interviewed by David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi

WILLIAM WINTER AND THE POLITICS OF RACIAL MODERATION 335 William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi by Charles C. Bolton On May 12, 2008, William F. Winter received the Profile in Courage Award from the John F. Kennedy Foundation, which honored the former Mississippi governor for “championing public education and racial equality.” The award was certainly well deserved and highlighted two important legacies of one of Mississippi’s most important public servants in the post–World War II era. During Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s presentation of the award, he noted that Winter had been criticized “for his integrationist stances” that led to his defeat in the gubernatorial campaign of 1967. Although Winter’s opponents that year certainly tried to paint him as a moderate (or worse yet, a liberal) and as less than a true believer in racial segregation, he would be the first to admit that he did not advocate racial integration in 1967; indeed, much to his regret later, Winter actually pandered to white segregationists in a vain attempt to win the election. Because Winter, over the course of his long career, has increasingly become identified as a champion of racial justice, it is easy, as Senator Kennedy’s remarks illustrate, to flatten the complexity of Winter’s evolution on the issue CHARLES C. BOLTON is the guest editor of this special edition of the Journal of Mississippi History focusing on the career of William F. Winter. He is profes- sor and head of the history department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Lyceum-The Circle Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: University Circle Not for publication: City/Town: Oxford Vicinity: State: Mississippi County: Lafayette Code: 071 Zip Code: 38655 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: X Public-State: X Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 buildings buildings 1 sites sites 1 structures structures 2 objects objects 12 Total Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: ___ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Supreme Court of the United States ———— RIMS BARBER, Et Al., Petitioners, V

No. 17-___ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— RIMS BARBER, et al., Petitioners, v. GOVERNOR PHIL BRYANT, et al., Respondents. ———— On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ———— PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ———— PAUL SMITH DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. 600 New Jersey Ave. NW Counsel of Record Washington, DC 20001 GINGER D. ANDERS ADELE M. EL-KHOURI MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 1155 F Street NW 7th Floor Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 220-1100 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners October 10, 2017 ROBERT B. MCDUFF SUSAN L. SOMMER 767 North Congress Street LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE & Jackson, MS 39202 EDUCATION FUND, INC. 120 Wall Street, 19th Floor BETH L. ORLANSKY New York, NY 10005 MISSISSIPPI CENTER FOR JUSTICE ELIZABETH LITTRELL P.O. Box 1023 LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE & Jackson, MS 39215-1023 EDUCATION FUND, INC. 730 Peachtree Street Suite 640 Atlanta, GA 30308 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED In Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015), this Court held that the Constitution entitles same- sex couples to join in civil marriage on the same terms as different-sex couples. In response, Missis- sippi enacted the Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act, Miss. Code Ann. § 11-62-1 et seq. (2016) (“HB 1523”). HB 1523 grants broad immunity to any person who commits enumerated acts of discrimination on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions opposing mar- riage of same-sex couples; transgender individuals; and sexual relations outside of a male-female mar- riage. The court of appeals held that petitioners, who do not share the endorsed beliefs, lack standing un- der the Establishment Clause because the religious endorsement takes the form of a statute rather than a religious display that they can physically encoun- ter, and held that they lack standing under the Equal Protection Clause because they have suffered no unequal treatment. -

Barber V. Bryant, No

Case 3:16-cv-00442-CWR-LRA Document 35 Filed 06/30/16 Page 1 of 60 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI NORTHERN DIVISION RIMS BARBER; CAROL BURNETT; PLAINTIFFS JOAN BAILEY; KATHERINE ELIZABETH DAY; ANTHONY LAINE BOYETTE; DON FORTENBERRY; SUSAN GLISSON; DERRICK JOHNSON; DOROTHY C. TRIPLETT; RENICK TAYLOR; BRANDIILYNE MANGUM- DEAR; SUSAN MANGUM; JOSHUA GENERATION METROPOLITAN COMMUNITY CHURCH; CAMPAIGN FOR SOUTHERN EQUALITY; and SUSAN HROSTOWSKI CAUSE NO. 3:16-CV-417-CWR-LRA V. consolidated with CAUSE NO. 3:16-CV-442-CWR-LRA PHIL BRYANT, Governor; JIM HOOD, DEFENDANTS Attorney General; JOHN DAVIS, Executive Director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services; and JUDY MOULDER, State Registrar of Vital Records MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER The plaintiffs filed these suits to enjoin a new state law, “House Bill 1523,” before it goes into effect on July 1, 2016. They contend that the law violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. The Attorney General’s Office has entered its appearance to defend HB 1523. The parties briefed the relevant issues and presented evidence and argument at a joint hearing on June 23 and 24, 2016. The United States Supreme Court has spoken clearly on the constitutional principles at stake. Under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, a state “may not aid, foster, or Case 3:16-cv-00442-CWR-LRA Document 35 Filed 06/30/16 Page 2 of 60 promote one religion or religious theory against another.” Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97, 104 (1968). “When the government acts with the ostensible and predominant purpose of advancing religion, it violates that central Establishment Clause value of official religious neutrality, there being no neutrality when the government’s ostensible object is to take sides.” McCreary Cnty., Kentucky v. -

Barber, Frank Interviewer

Copyright protected. Use of this item beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission of Delta State University is required to publish or reproduce. Contact University Archives, Delta State University, (662) 846-4780. Interviewee: Barber, Frank Interviewer: Mohammed, Liz Date: October 20, 1983 LM: This is an interview with Frank Barber. Okay, please give us a brief biographical sketch to include your date of birth, place of birth, and schools attended. FB: Well, I was born April 2, 1929, in Hot Springs, Garland Co., Arkansas. My mother was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in 1902 and we happened to be in Hot Springs because my mother had moved there five years before my birth for her health. My father had to sell his business and relocate in Hot Springs. But apparently, my mother recovered sufficiently to have me in 1929. I only lived in Hot Springs about three years and I grew up in Hattiesburg, Forrest Co. Mississippi. And, received my elementary education there, and was graduated from High School there, in Hattiesburg, in 1947. I attended the University of Mississippi, I went to the U.S. Army, I was graduated with a BA Degree from the University of Southern Mississippi, then Mississippi Southern College, Hattiesburg. I attended the University of Mississippi, Ole Miss School of Law one year, and was graduated after two years at the George Washington University School of Law in Washington D.C. I'm a lawyer, I am_____to the D.C. -

![Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1980] Mississippi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7660/biographical-data-of-members-of-senate-and-house-personnel-of-standing-committees-1980-mississippi-2327660.webp)

Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1980] Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Mississippi Legislature Hand Books State of Mississippi Government Documents 1980 Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1980] Mississippi. Legislature Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Mississippi. Legislature, "Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1980]" (1980). Mississippi Legislature Hand Books. 15. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the State of Mississippi Government Documents at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi Legislature Hand Books by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST.DOC. 1982 gislative Handbook 4630 24 ,. JAN 19 1980-198 Charles H. Griffin Secretary of the Senate Charles J. Jackson, Jr. Clerk of the House OF SENATE TELEPHONEDIRECTORY ...3 54-6788 (Sessions Only) ......... .. .. .............. 948-7321 Pro Tern .......... ....... .. ... 354-7365 ecretary of the Senate .. .. ... 354 6790 Assistant Secretary ................. ....... ..... 354-6629 Appropriations .. .... ... .. .. ... .. .. ....... 354-6365 Bookkeeper. ........ .... .............. ....... 354-7047 Docket Room ... ... ....... .. .... 354-7432 Finance ......... ............... ... .......... .... 354-6761 Journal Clerk .......... ..... .. .. .. .. ...... .. 354-6529 Judiciary -

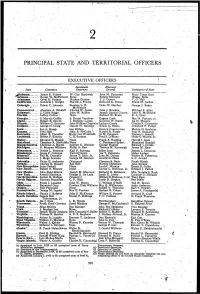

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2011 Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010 Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buzard-Boyett, Patricia Michelle, "Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010" (2011). Dissertations. 740. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/740 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Dr. William K. Scarborough Director Dr. Bradley G. Bond Dr. Curtis Austin Dr. Andrew Wiest Dr. Louis Kyriakoudes Dr. Susan A. Siltanen Dean of the Graduate School May 2011 The University of Southern Mississippi RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 ABSTRACT RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett May 2011 “Race and Justice in Mississippi’s Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010,” examines the black freedom struggle in Jones and Forrest counties. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abernethy, Thomas G. 273, 279, 290, 324, 345 Great Emigration 272, 281 abortion 306, 457–9 gubernatorial election of 1991 373 Ackia, battle of 32 health 201–2, 360 actors 265–6 Johnson, Jr. administration 325 Adam, Bidwell 230, 237 Mabus administration 371–2 Adams, John 54 mid-twentieth century 342 Adams, John Quincy 81, 89, 90 music 257 Adams, Robert H. 82 poetry 255–6 Afghanistan conflict 461 population trends 331, 353–4, 355, 356 African Americans poverty 362 1927 flood 226, 227–9 presidential election of 2008 431 1950s 283, 285 progressive “rednecks” 207 Allain administration 370 recent political trends 365, 367, 378 antebellum 109–14, 119 Reconstruction 153–5, 156, 157, 158, 159, Bailey administration 278 161, 163–4, 165, 166 Bilbo administration 213, 280 religion 199–200, 201, 297, 298, 299, 303–5 Coleman administration 292, 293 Republican party 170, 229, 324, 325 congressional elections of 2003 430 Roosevelt, Franklin D. administration 279 Constitution of 1890 176–8, 181 Russell administration 220 Democratic party 170, 181, 290, 325, 326–7, Second Reconstruction 309 348, 425 sharecropping 188–9 education 194–5, 196, 197–9, 278, 288–90, statewide elections of 2011 433 381–7, 392, 393, 395,COPYRIGHTED 396 suffrage MATERIAL 279, 280 farm owners 332, 333 twentieth-century transitions 343 Finch administration 347 twenty-first century 460 fine arts 262–3, 264 Vietnam war 327 first judge 370 Waller administration 343–4 Fordice administration 375 White’s second administration 288–90, 291 free blacks 114 Williams administration 326 Great Depression 236 Winter administration 367, 369 Mississippi: A History, Second Edition. -

Hinds County Bar Association Making Our Case for a Better Community April 2008

HINDS COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION MAKING OUR CASE FOR A BETTER COMMUNITY APRIL 2008 members are serving on the various llCilA comminecs, and President's Column they have been hard at work. Just recently, the HCBA by David Kaufman Womc11 in the ProfCssiou (.\nnmittee partnered with the Mis~issippi Women's Lawyt:rs A~sociation to present a lunch Time !lies when you arc having program with area attorneys to discuss rainmaking for ft:malc lim. I\ !though as I write this column f attorneys. Barbara Childs \Va!laec, Sharon Bridges, ( "hristine have a little less than two months tlnldberg, and Rebecca Wiggs presented at this well-attended remaining in my term as President, this and informative event. The \Vmncn in the Profession will be my last opportunity to address Committee also recently sent a delegation of speakers to all of the members. SufTicc it to say. it address the Pre-Law Society at Tcmgaloo College to answer has been a privilege to scrw: as Prcsiclcnt of om organization, the students' questions regarding law school and legal career und J have truly cnjoyn! having the opportunity to get to opportunities following graduation. The pr(lgfl\m was a great know and work with so many or ymt in connection wilh all of !;llccc~s, aud the ( "ommittee is planning additional programs the activities in which the IICBA is involved. Thanks to all at other scho(lls in t11e ncar future. Our special thanks to of the many volunteers who lmvc chaired and served on the committee members Let\ nne Brady, Rhea Sheldon, and vari(lus committees duri11g the past year. -

Vol. Lvii Spring 2011 No. 3 Horne Fraud, Forensic & Litigation Services

VOL. LVII SPRING 2011 NO. 3 HORNE FRAUD, FORENSIC & LITIGATION SERVICES The Fraud, Forensic & Litigation team at HORNE LLP provides a comprehensive range of services within the forensic accounting profession. Our team members are credentialed in focused practice areas with emphasis on economic damages, valuation, internal audit, fraud and financial forensics. As a top 50 business advisory and accounting firm nationally, the Fraud, Forensic & Litigation team has access to internal resources such as tax, auditing, construction, health care, franchising and financial institutions. Robert H. Alexander, Jr. Jeffrey N. Aucoin OUR SERVICES INCLUDE: CPA/ABV, ASA CPA, CFF, CFE, CIA UÊ VVÊ >>}ià - Lost Profits Calculation - Lost Business Value - Business Interruption UÊ *iÀÃ>ÊÕÀÞÉ7À}vÕÊ/iÀ>Ì - Calculation Analysis and Consultation - Economic Damage Report UÊ Ý«iÀÌÊ7ÌiÃÃÊ/iÃÌÞ - Qualified in Federal/ State Courts - Understandable Jury Presentations UÊ À>Õ`Ê Lori T. Liddell Paul E. Foster - Investigation and CPA CPA Quantification of Loss - Recovery Assistance - Prevention and Monitoring UÊ ÕÃiÃÃÊ6>Õ>Ìà - Estate/Gift Tax - Business Planning - Marital Dissolutions UÊ VVÊ>ÞÃà - Feasibility Studies - Due Diligence HORNE’s team strives to deliver unbiased experience in situations ranging from complex valuation issues to litigation engagements. 601-326-1000 www.horneffl.com ALABAMA | LOUISIANA | MISSISSIPPI | TENNESSEE | TEXAS © HORNE LLP 2011 • Is your firm’s 401(k) subject to quarterly WHO’S reviews by an independent board of directors? WATCHING • Does it include -

Celebrate America Balloon Glow Heatwave Classic Triathlon Father's Day Fishing Tournament RECRE8 Mobile

June 2013–August 2013 Celebrate America Balloon Glow Heatwave Classic Triathlon Father’s Day Fishing Tournament RECRE8 Mobile App RIDGELAND, MS the SUMMER issue From the Mayor By the time this edition of Ridgeland Life reaches your mail boxes, the school year will have ended. With the end of the school year comes much excitement as the students look forward to summer vacation and more time with their family and friends. I would like to share my congratulations to all the graduating seniors; you should be proud of your accomplishments. I know each of you look forward to the next phase of your life, whether it be starting a vocation or going on to a college that suits your chosen field. I think if you look at our graduating seniors this year, it’s exciting to see that Ridgeland has such outstanding students. With over $1.5 million offered in scholarships to Ridgeland High School students, there is no doubt that the Titan Class of 2013 has been prepared well for college through Madison County Schools and that the graduates will bring intelligence and ambition for the betterment of Gene McGee society. lt’s a great feeling to know that the future Mayor of Ridgeland of Ridgeland, Mississippi and America will be in such talented hands in the future. This past year, l’ve seen many outstanding accomplishments in our schools. The recognitions and awards are too many to name, but I would just like to congratulate each student for a job well done and to let you know that we, the City Administration is proud of each of you.