Double Dividend and Distribution of Welfare: Advanced Results and Empirical Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note on Taxation System

Note on Taxation system Introduction Today an important problem against each government is that how to get income temporarily by debt also, but they have to return it after some time. Some government income is received from government enterprises, administrative and judicial tasks and other such sources, but a big part of government income is received from taxation. Taxes: - Taxes are those compulsory payments which are used without any such hope towards government by tax payers that they will get direct benefit in return of them. According to Prof. Seligman, ‘’ Tax is that compulsory contribution given to Government by individuals which is paid in the payment of expenses in all general favours and no special benefit is given in lieu of that.’’ According to Trussing, ‘’The special thing is that in regard of tax in comparison to all amounts taken by government, quid pro quo is not found directly between taxpayer and government administration in it.’’ Characteristics of a Tax It is clear by above mentioned definitions that some specialties are found in tax which are as follows: - (1) Compulsory Contribution—Tax is a contribution given to state by people living within the premises of country due to residence and property etc. or by citizens and this contribution is given for general use only. Though it is a compulsory contribution, therefore, no individual can deny from the payment of tax. For example, no person can say that he is not getting benefit from some services provided by that state or he didn’t get the right to vote, therefore, he is not bound to pay tax. -

Discussion Paper on Tax Policy and Tax Principles in Sweden, 1902-2016

H2020-EURO-SOCIETY-2014 JANUARY 2017 Discussion Paper on Tax Policy and Tax Principles in Sweden, 1902-2016 Åsa Gunnarsson, Umeå University, Forum for Studies on Law and Society. E-mail: [email protected] Martin Eriksson, Umeå University, Forum for Studies on Law and Society. E-mail: [email protected] The FairTax project is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme 2014-2018, grant agreement No. FairTax 649439 FairTax WP-Series No.8 Discussion Paper on Tax Policy and Tax Principles in Sweden, 1902-2016 2 FairTax WP-Series No.8 Discussion Paper on Tax Policy and Tax Principles in Sweden, 1902-2016 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6 2. The Swedish doctrine of tax principles. A twilight zone between legal principles and tax policy norms. ........................................................................................................................... 9 3. The ability-to-pay principle and the creation of the modern tax system, 1900-1928 .... 11 4. Public expenditures, full employment and the formation of the welfare state, 1932-1947 12 5. The 1960s: introducing VAT, upholding redistribution ................................................. 15 6. The 1971 tax reform: individual taxation, redistribution and social justice ................. -

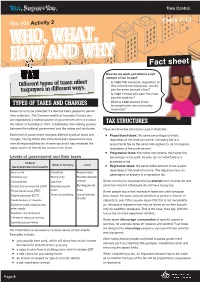

WHO, WHAT, HOW and WHY Fact Sheet

Ta x , Super+You. Take Control. Years 7-12 Tax 101 Activity 2 WHO, WHAT, HOW AND WHY Fact sheet How do we work out what is a fair amount of tax to pay? • Is it fair that everyone, regardless of Different types of taxes affect their income and expenses, should taxpayers in different ways. pay the same amount of tax? • Is it fair if those who earn the most pay the most tax? • What is a fair amount of tax TYPES OF TAXES AND CHARGES for people who use community resources? Taxes can only be collected if a law has been passed to permit their collection. The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act established a federal system of government when it created TAX STRUCTURES the nation of Australia in 1901. It distributes law-making powers between the national government and the states and territories. There are three tax structures used in Australia: Each level of government imposes different types of taxes and Proportional taxes: the same percentage is levied, charges. During World War II the Australian Government took regardless of the level of income. Company tax is a over all responsibilities for income tax and it has remained the proportional tax as the same rate applies for all companies, major source of federal tax revenue ever since. regardless of the profit earned. Progressive taxes: the higher the income, the higher the Levels of government and their taxes percentage of tax paid. Income tax for individuals is a Federal progressive tax. State or territory Local (Australian/Commonwealth) Regressive taxes: the same dollar amount of tax is paid, regardless of the level of income. -

Charging Drivers by the Pound: the Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System

Charging Drivers by the Pound The Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System Davide Cerruti, Anna Alberini, and Joshua Linn MAY 2017 Charging Drivers by the Pound: The Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System Davide Cerruti, Anna Alberini, and Joshua Linn Abstract Policymakers have been considering vehicle and fuel taxes to reduce transportation greenhouse gas emissions, but there is little evidence on the relative efficacy of these approaches. We examine an annual vehicle registration tax, the Vehicle Excise Duty (VED), which is based on carbon emissions rates. The United Kingdom first adopted the system in 2001 and made substantial changes to it in the following years. Using a highly disaggregated dataset of UK monthly registrations and characteristics of new cars, we estimate the effect of the VED on new vehicle registrations and carbon emissions. The VED increased the adoption of low-emissions vehicles and discouraged the purchase of very polluting vehicles, but it had a small effect on aggregate emissions. Using the empirical estimates, we compare the VED with hypothetical taxes that are proportional either to carbon emissions rates or to carbon emissions. The VED reduces total emissions twice as much as the emissions rate tax but by half as much as the emissions tax. Much of the advantage of the emissions tax arises from adjustments in miles driven, rather than the composition of new car sales. Key Words: CO2 emissions, vehicle registration fees, carbon taxes, vehicle excise duty, UK JEL Codes: H23, Q48, Q54, R48 Contact: [email protected]. Cerruti: postdoctoral researcher, Center for Energy Policy and Economics, ETH Zurich; Alberini: professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Maryland; Linn: senior fellow, Resources for the Future. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

Taxes and Government Spending 14 SECTION 1 WHAT ARE TAXES? TEXT SUMMARY Taxes Are Payments That People Are Subject to a Tax

CHAPTER Taxes and Government Spending 14 SECTION 1 WHAT ARE TAXES? TEXT SUMMARY Taxes are payments that people are subject to a tax. It also decides how to required to pay to a local, state, or national structure the tax. The three basic kinds of government. Taxes supply revenue, or tax structures are proportional, progres- income, to provide the goods sive, and regressive. A proportional tax THE BIG IDEA and services that people expect is a tax in which the percentage of income Government collects from government. paid in taxes remains the same for all money to run its The Constitution grants income levels. A progressive tax is one programs through Congress the power to tax and in which the percentage increases at different types also limits the kinds of taxes higher income levels. An example is the of taxes. Congress can impose. Federal individual income tax, a tax on a per- taxes must be for the “common son’s income, which requires people defense and general welfare,” with higher incomes to pay a higher per- must be the same in all states, and may not centage of their incomes in taxes. In a be placed on exports. The Sixteenth regressive tax, the percentage increases Amendment, ratified in 1913, gave Con- at lower income levels. A sales tax, a tax gress the power to levy an income tax. on the value of a good or service being When government creates a tax, it sold, is regressive because higher-income decides on the type of tax base—the people pay a lower proportion of their income, property, good, or service that is incomes on goods and services. -

International Tax Policy for the 21St Century

NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 147 The NFTC Foreign Income Project: International Tax Policy for the 21st Century Part Two Relief of International Double Taxation NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 148 NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 149 Origins of the Foreign Tax Credit Chapter 1 Origins of the Foreign Tax Credit I. Introduction The United States’ current system for taxing international income was creat- ed during the period from 1918 through 1928.1 From the introduction of 149 the income tax (in 1913 for individuals and in 1909 for corporations) until 1918, foreign taxes were deducted in the same way as any other business expense.2 In 1918, the United States enacted the foreign tax credit,3 a unilat- eral step taken fundamentally to redress the unfairness of “double taxation” of foreign-source income. By way of contrast, until the 1940s, the United Kingdom allowed a credit only for foreign taxes paid within the British 1 For further description and analysis of this formative period of U.S. international income tax policy, see Michael J. Graetz & Michael M. O’Hear, The ‘Original Intent’ of U.S. International Taxation, 46 DUKE L.J. 1021, 1026 (1997) [hereinafter “Graetz & O’Hear”]. The material in this chapter is largely taken from this source. 2 The reasoning behind the international tax aspects of the 1913 Act is difficult to discern from the historical sources. One scholar has concluded “it is quite likely that Congress gave little or no thought to the effect of the Revenue Act of 1913 on the foreign income of U.S. -

How Should Capital Be Taxed? the Swedish Experience

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11475 How Should Capital Be Taxed? Theory and Evidence from Sweden Spencer Bastani Daniel Waldenström APRIL 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11475 How Should Capital Be Taxed? Theory and Evidence from Sweden Spencer Bastani Linnaeus University and CESifo Daniel Waldenström IFN, Paris School of Economics, CEPR and IZA APRIL 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11475 APRIL 2018 ABSTRACT How Should Capital Be Taxed? Theory and Evidence from Sweden* This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the role of capital taxation in advanced economies with a focus on the Swedish experience. -

The Dual Income Tax: Implementation and Experience in European Countries

International Studies Program Working Paper 06-25 December 2006 The Dual Income Tax: Implementation and Experience in European Countries Bernd Genser International Studies Program Working Paper 06-25 The Dual Income Tax: Implementation and Experience in European Countries Bernd Genser December 2006 International Studies Program Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Georgia State University Atlanta, Georgia 30303 United States of America Phone: (404) 651-1144 Fax: (404) 651-4449 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://isp-aysps.gsu.edu Copyright 2006, the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the copyright owner. International Studies Program Andrew Young School of Policy Studies The Andrew Young School of Policy Studies was established at Georgia State University with the objective of promoting excellence in the design, implementation, and evaluation of public policy. In addition to two academic departments (economics and public administration), the Andrew Young School houses seven leading research centers and policy programs, including the International Studies Program. The mission of the International Studies Program is to provide academic and professional training, applied research, and technical assistance in support of sound public policy and sustainable economic growth in developing and transitional economies. The International Studies Program at the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies is recognized worldwide for its efforts in support of economic and public policy reforms through technical assistance and training around the world. This reputation has been built serving a diverse client base, including the World Bank, the U.S. -

Carbon Taxation in Sweden

Carbon Taxation in Sweden January, 2021 Ministry of Finance 1 How to Reach … Climate, Environment and Energy Policy Goals? Using environmental taxes in a cost-effective way …. • … is Sweden’s primary instrument to reach set goals • … is easy to administer and gives results • … may need to include state aid elements to ensure best overall environmental results Ministry of Finance 2 The Swedish Context Increased Focus on Environmental Taxes 1990’s and onwards Now Environmental issues given high priority by Government and citizens Energy tax: fiscal and energy • increased focus on efficiency Until 1980’s environmental taxes Primarily fiscal purposes • increased tax levels, step- Carbon tax: by-step climate • focus on increased carbon generally low tax levels tax share of taxation of energy (“carbon tax heavy”) Ministry of Finance 3 30 Years of Carbon Taxation Swedish Experiences Carbon Tax 1988-1989 Committee of Inquiry 1989 Committee Report 1990 Governmental Bill and Parliament Decision 1991 Carbon Tax introduced New national climate targets 2017 Decided by Parliament Ministry of Finance 4 The Swedish Carbon Tax in 1991 …. part of a major tax reform • Reduced and simplified labour taxes ▼ - 6 billion $ • Value Added Tax on energy ▲ + 1.8 billion $ • Carbon tax introduced at a low levels combined with approx. 50% cuts in energy tax rates ▲ + 0.4 billion $ • Certain investment state aid measures Ministry of Finance 5 By 2030 Emissions from domestic transports* reduced by 70 % compared to 2010 * excluding aviation Finansdepartementet 6 By 2045 -

Explanation of Proposed Protocol to the Income Tax Treaty Between the United States and Sweden

EXPLANATION OF PROPOSED PROTOCOL TO THE INCOME TAX TREATY BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND SWEDEN Scheduled for a Hearing Before the COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE On February 2, 2006 ____________ Prepared by the Staff of the JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION January 26, 2006 JCX-1-06 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 I. SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................. 2 II. OVERVIEW OF U.S. TAXATION OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND INVESTMENT AND U.S. TAX TREATIES .......................................................................... 4 A. U.S. Tax Rules .................................................................................................................... 4 B. U.S. Tax Treaties ................................................................................................................ 6 III. OVERVIEW OF TAXATION IN SWEDEN........................................................................... 8 A. National Income Taxes....................................................................................................... 8 B. International Aspects of Taxation in Sweden ................................................................... 10 C. Other Taxes....................................................................................................................... 11 IV. THE UNITED STATES AND SWEDEN: -

The Origins of High Compliancein the Swedish Tax State

Getting to Sweden University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online The Leap of Faith: The Fiscal Foundations of Successful Government in Europe and America Sven H. Steinmo Print publication date: 2018 Print ISBN-13: 9780198796817 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198796817.001.0001 Getting to Sweden The Origins of High Compliancein the Swedish Tax State Marina Nistotskaya Michelle D’Arcy DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198796817.003.0002 Abstract and Keywords This chapter argues that the roots of Sweden’s exceptional tax state lie in the early modern period. From c.1530 the state began monitoring economic activity and developing a direct vertical fiscal contract between the king and his subjects. The extensive data collected by the state, with the assistance of the newly reformed Church, facilitated fairness in the distribution of tax and conscription burdens and fostered a horizontal contract between subjects. With a free peasantry and a weak nobility, the state’s relationship with the peasantry was direct and unmediated. Furthermore, late industrialization preserved a tax structure and administration based on direct taxes that could easily adapt to the collection of modern taxes. Taken together, these factors explain how Sweden, over the course of 400 years, cultivated its fiscal capacity and strengthened the fiscal contract between ordinary taxpayers and the state. Keywords: fiscal capacity, taxation, Sweden, state-building, institutionalism, early modern Europe, cadaster Introduction Page 1 of 28 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2019. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy).