FIDE ETHICS COMMISSION MOTIVATION Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

2020-21 Candidates Tournament ROUND 9

2020-21 Candidates Tournament ROUND 9 CATALAN OPENING (E05) easy to remove and will work together with the GM Anish Giri (2776) other pieces to create some long-term ideas. GM Wang Hao (2763) A game between two other top players went: 2020-2021 Candidates Tournament 14. Rac1 Nb4 15. Rfd1 Ra6 (15. ... Bxf3! 16. Bxf3 Yekaterinburg, RUS (9.3), 04.20.2021 c6 is the most solid approach in my opinion. I Annotations by GM Jacob Aagaard cannot see a valid reason why the bishop on f3 for Chess Life Online is a strong piece.) 16. Qe2 Nbd5 17. Nb5 Ne7 18. The Game of the Day, at least in terms of Nd2 Bxg2 19. Kxg2 Nfd5 20. Nc4 Ng6 21. Kh1 drama, was definitely GM Ding Liren versus Qe7 22. b3 Rd8 23. Rd2 Raa8 24. Rdc2 Nb4 25. GM Maxime Vachier-Lagrave. Drama often Rd2 Nd5 26. Rdc2, and the game was drawn in Ivanchuk – Dominguez Perez, Varadero 2016. means bad moves, which was definitely the case there. Equally important for the tournament 14. ... Bxg2 15. Kxg2 c6 16. h3!N 8. ... Bd7 standings was the one win of the day. GM Anish Giri moves into shared second place with this The bishop is superfluous and will be The real novelty of the game, and not a win over GM Wang Hao. exchanged. spectacular one. The idea is simply that the king The narrative of the game is a common one hides on h2 and in many situations leaves the 9. Qxc4 Bc6 10. Bf4 Bd6 11. -

A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague – Candidates Tournament 2020

A FEAST OF CHESS IN TIME OF PLAGUE CANDIDATES TOURNAMENT 2020 Part 1 — Yekaterinburg by Vladimir Tukmakov www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniël Vanheirzeele Translator Izyaslav Koza Proofreader Bob Holliman Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Mieke Mertens Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague. Candidates Tournament 2020. Part 1 — Yekaterinburg Copyright © 2020 Vladimir Tukmakov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-092-1 D/2020/13730/26 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PRELUDE 11 THE PLAY Round 1 21 Round 2 44 Round 3 61 Round 4 80 Round 5 94 Round 6 110 Round 7 127 Final — Round 8 141 UNEXPECTED CONCLUSION 143 INTERIM RESULTS 147 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! a good move ?a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move only move =equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrifi ced material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage Black has a serious advantage +– White has a decisive advantage –+ Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is worse is Nnovelty +check #mate INTRODUCTION In the middle of the last century tournament compilations were ex- tremely popular. -

Kasparov's Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM

California Chess Journal Volume 20, Number 2 April 1st 2004 $4.50 Kasparov’s Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM Scrambles to Build 25 Deep Blues! Past Vs Future Special Issue • Young Fischer Fires Up S.F. • Fischer commentates 4 Boyscouts • Building your “Super Computer” • Building Fischer’s Dream House • Raise $500 playing chess! • Fischer Articles Galore! California Chess Journal Table of Con tents 2004 Cal Chess Scholastic Championships The annual scholastic tourney finishes in Santa Clara.......................................................3 FISCHER AND THE DEEP BLUE Editor: Eric Hicks Contributors: Daren Dillinger A miracle has happened in the Phillipines!......................................................................4 FM Eric Schiller IM John Donaldson Why Every Chess Player Needs a Computer Photographers: Richard Shorman Some titles speak for themselves......................................................................................5 Historical Consul: Kerry Lawless Founding Editor: Hans Poschmann Building Your Chess Dream Machine Some helpful hints when shopping for a silicon chess opponent........................................6 CalChess Board Young Fischer in San Francisco 1957 A complet accounting of an untold story that happened here in the bay area...................12 President: Elizabeth Shaughnessy Vice-President: Josh Bowman 1957 Fischer Game Spotlight Treasurer: Richard Peterson One game from the tournament commentated move by move.........................................16 Members at -

Finding Checkmate in N Moves in Chess Using Backtracking And

Finding Checkmate in N moves in Chess using Backtracking and Depth Limited Search Algorithm Moch. Nafkhan Alzamzami 13518132 Informatics Engineering School of Electrical Engineering and Informatics Institute Technology of Bandung, Jalan Ganesha 10 Bandung [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—There have been many checkmate potentials that has pieces of a dark color. There are rules about how pieces players seem to miss. Players have been training for finding move, and about taking the opponent's pieces off the board. checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems can The player with white pieces always makes the first move.[4] be solved using a simple depth-limited search and backtracking Because of this, White has a small advantage, and wins more algorithm with legal moves as the searching paths. often than Black in tournament games.[5][6] Keywords—chess; checkmate; depth-limited search; Chess is played on a square board divided into eight rows backtracking; graph; of squares called ranks and eight columns called files, with a dark square in each player's lower left corner.[8] This is I. INTRODUCTION altogether 64 squares. The colors of the squares are laid out in There have been many checkmate potentials that players a checker (chequer) pattern in light and dark squares. To make seem to miss. Players have been training for finding speaking and writing about chess easy, each square has a checkmates through chess checkmate puzzles. Such problems name. Each rank has a number from 1 to 8, and each file a can be solved using a simple depth-limited search and letter from a to h. -

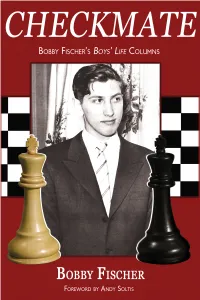

Checkmate Bobby Fischer's Boys' Life Columns

Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer Foreword by Andy Soltis 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer ISBN: 978-1-941270-51-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-941270-52-3 (eBook) © Copyright 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. & Hanon W. Russell All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Chess columns written by Bobby Fischer appeared from December 1966 through January 1970 in the magazine Boys’ Life, published by the Boy Scouts of America. Russell Enterprises, Inc. thanks the Boy Scouts of America for its permission to reprint these columns in this compilation. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Editing and proofreading by Peter Kurzdorfer Cover by Janel Lowrance 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 April 53 by Andy Soltis May 59 From the Publisher 6 Timeline 60 June 61 July 69 Timeline 7 Timeline 70 August 71 1966 September 77 December 9 October 78 November 84 1967 February 11 1969 March 17 February 85 April 19 March 90 Timeline 22 May 23 April 91 June 24 July 31 May 98 Timeline 32 June 99 August 33 July 107 September 37 August 108 Timeline 38 September 115 October 39 October 116 November 46 November 122 December 123 1968 February 47 1970 March 52 January 128 3 Checkmate Foreword Bobby Fischer’s victory over Emil Nikolic at Vinkovci 1968 is one of his most spectacular, perhaps the last great game he played in which he was the bold, go-for-mate sacrificer of his earlier years. -

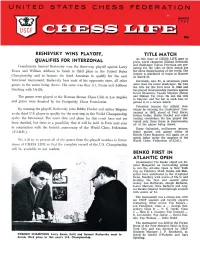

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security?

1 Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security? Gildas Avoine, Cedric´ Lauradoux, Rolando Trujillo-Rasua F Abstract—The main concern of chess referees is to prevent are indeed playing against each other, instead of players from biasing the outcome of the game by either collud- playing against a little girl as one’s would expect. ing or receiving external advice. Preventing third parties from Conway’s work on the chess grandmaster prob- interfering in a game is challenging given that communication lem was pursued and extended to authentication technologies are steadily improved and miniaturized. Chess protocols by Desmedt, Goutier and Bengio [3] in or- actually faces similar threats to those already encountered in der to break the Feige-Fiat-Shamir protocol [4]. The computer security. We describe chess frauds and link them to their analogues in the digital world. Based on these transpo- attack was called mafia fraud, as a reference to the sitions, we advocate for a set of countermeasures to enforce famous Shamir’s claim: “I can go to a mafia-owned fairness in chess. store a million times and they will not be able to misrepresent themselves as me.” Desmedt et al. Index Terms—Security, Chess, Fraud. proved that Shamir was wrong via a simple appli- cation of Conway’s chess grandmaster problem to authentication protocols. Since then, this attack has 1 INTRODUCTION been used in various domains such as contactless Chess still fascinates generations of computer sci- credit cards, electronic passports, vehicle keyless entists. Many great researchers such as John von remote systems, and wireless sensor networks. -

Assessing Human Error Against a Benchmark of Perfection

Assessing Human Error Against a Benchmark of Perfection Ashton Anderson Jon Kleinberg Sendhil Mullainathan Microsoft Research Cornell University Harvard University ABSTRACT to the canonical set-up in machine learning applications. Typically, An increasing number of domains are providing us with detailed using instances of decision problems together with “ground truth” trace data on human decisions in settings where we can evaluate the showing the correct decision, an algorithm is trained to produce quality of these decisions via an algorithm. Motivated by this de- the correct decisions in a large fraction of instances. The analy- velopment, an emerging line of work has begun to consider whether sis of human error, on the other hand, represents a twist on this we can characterize and predict the kinds of decisions where people formulation: given instances of a task in which we have both the are likely to make errors. correct decision and a human’s decision, the algorithm is trained To investigate what a general framework for human error predic- to recognize future instances on which the human is likely to make tion might look like, we focus on a model system with a rich history a mistake. Predicting human error from this type of trace data has in the behavioral sciences: the decisions made by chess players as a history in human factors research [14, 24], and a nascent line of they select moves in a game. We carry out our analysis at a large work has begun to apply current machine-learning methods to the scale, employing datasets with several million recorded games, and question [16, 17]. -

On the Limits of Engine Analysis for Cheating Detection in Chess

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kent Academic Repository computers & security 48 (2015) 58e73 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cose On the limits of engine analysis for cheating detection in chess * David J. Barnes , Julio Hernandez-Castro School of Computing, The University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NF, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: The integrity of online games has important economic consequences for both the gaming Received 12 July 2014 industry and players of all levels, from professionals to amateurs. Where there is a high Received in revised form likelihood of cheating, there is a loss of trust and players will be reluctant to participate d 14 September 2014 particularly if this is likely to cost them money. Accepted 10 October 2014 Chess is a game that has been established online for around 25 years and is played over Available online 22 October 2014 the Internet commercially. In that environment, where players are not physically present “over the board” (OTB), chess is one of the most easily exploitable games by those who wish Keywords: to cheat, because of the widespread availability of very strong chess-playing programs. Chess Allegations of cheating even in OTB games have increased significantly in recent years, and Cheating even led to recent changes in the laws of the game that potentially impinge upon players’ Online games privacy. Privacy In this work, we examine some of the difficulties inherent in identifying the covert use Machine assistance of chess-playing programs purely from an analysis of the moves of a game. -

Blood and Thunder, Thud and Blunder

XABCDEFGHY The Black queen edges closer to 8r+-+-trk+( the White king and it is a question CHESS 7zppwqnvlpzp-’ of which side can strike first. January 3rd 2009 6-+p+psn-zp& 5+-+-+-+P% 29.h5-h6 Qc5-a3+ Michael 4-+PzPN+-+$ 30.Kc1–d1 Qa3xa2 3+-+Q+N+-# Adams 2PzP-vL-zPP+" The players have skilfully threaded 1+-mKR+-+R! their way through a minefield xabcdefghy of complications so far, but now one blunder is enough to lose in Bacrot, E - Leko, P this razor-sharp position. After Elista the correct 30...g7-g6 31.Ne1xd3 Qa3xa2, things are still not that Blood and 17.g2-g4 clear. thunder, thud A standard idea to open lines on 31.Qe4-h7+ the kingside, but rare in this exact and blunder situation. This beautiful queen sacrifice brings down the curtain on 17... Nf6xg4 proceedings, Black resigns as There was a busy end to 18.Qd3-e2 f7-f5 31...Kg8xh7 (or 31...Kg8-f8 the year chess-wise with 19.Rd1–g1 Ra8-e8 32.Bd2-b4+) 32.h6xg7+ leads to the first Pearl Spring Super mate shortly. Tournament in Nanjing, China, Capturing the knight was another XABCDEFGHY which was a great success for possibility, 19...f5xe4 20.Qe2xe4 8-mkl+r+r+( Veselin Topalov and took his Nd7-f6 21.Qe4xe6+ Rf8-f7 7+-+-+p+-’ rating well north of 2800. 22.Nf3-e5 Ng4xe5 23.d4xe5 6pvl-zppzp-+& It was also time for the 3rd leads to a complicated position. 5+p+-wqP+-% FIDE Grand Prix, which was 4-+-+PsNPzp$ transferred from Doha to Elista 20.Nf3-e1 e6-e5 3+-zP-+-+P# less than three weeks before the 2PzPL+R+-+" scheduled start. -

Emirate of UAE with More Than Thirty Years of Chess Organizational Experience

DUBAI Emirate of UAE with more than thirty years of chess organizational experience. Many regional, continental and worldwide tournaments have been organized since the year 1985: The World Junior Chess Championship in Sharjah, UAE won by Max Dlugy in 1985, then the 1986 Chess Olympiad in Dubai won by USSR, the Asian Team Chess Championship won by the Philippines. Dubai hosted also the Asian Cities Championships in 1990, 1992 and 1996, the FIDE Grand Prix (Rapid, knock out) in 2002, the Arab Individual Championship in 1984, 1992 and 2004, and the World Blitz & Rapid Chess Championship 2014. Dubai Chess & Culture Club is established in 1979, as a member of the UAE Chess Federation and was proclaimed on 3/7/1981 by the Higher Council for Sports & Youth. It was first located in its previous premises in Deira–Dubai as a temporarily location for the new building to be over. Since its launching, the Dubai Chess & Culture Club has played a leading role in the chess activity in UAE, achieving for the country many successes on the international, continental and Arab levels. The Club has also played an imminent role through its administrative members who contributed in promoting chess and leading the chess activity along with their chess colleagues throughout UAE. “Sheikh Rashid Bin Hamdan Al Maktoum Cup” The Dubai Open championship, the SHEIKH RASHID BIN HAMDAN BIN RASHID AL MAKTOUM CUP, the strongest tournament in Arabic countries for many years, has been organized annually as an Open Festival since 1999, it attracts every year over 200 participants. Among the winners are Shakhriyar Mamedyarov (in the edition when Magnus Carlsen made his third and final GM norm at the Dubai Open of 2004), Wang Hao, Wesley So, or Gawain Jones.