The Thangmi of Nepal and India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin - 21

Food Security Bulletin - 21 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, November 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 21 Highlights Over the period July to September 2008, the number of people highly and severely food insecure increased by about 50% compared to the previous quarter due to severe flooding in the East and Western Terai districts, roads obstruction because of incessant rainfall and landslides, rise in food prices and decreased production of maize and other local crops. The food security situation in the flood affected districts of Eastern and Western Terai remains precarious, requiring close monitoring, while in the majority of other districts the food security situation is likely to improve in November-December due to harvesting of the paddy crop. Decreased maize and paddy production in some districts may indicate a deteriorating food insecurity situation from January onwards. this period. However, there is an could be achieved through the provision Overview expectation of deteriorating food security of return packages consisting of food Mid and Far-Western Nepal from January onwards as in most of the and other essentials as well as A considerable improvement in food Hill and Mountain districts excessive agriculture support to restore people’s security was observed in some Hill rainfall, floods, landslides, strong wind, livelihoods. districts such as Jajarkot, Bajura, and pest diseases have badly affected In the Western Terai, a recent rapid Dailekh, Rukum, Baitadi, and Darchula. maize production and consequently assessment conducted by WFP in These districts were severely or highly reduced food stocks much below what is November, revealed that the food food insecure during April - July 2008 normally expected during this time of the security situation is still critical in because of heavy loss in winter crops, year. -

PROPOSED HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT TAMAKOSHI 3 (TA3) August 2009 1

Information Brochure 01 PROPOSED HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT TAMAKOSHI 3 (TA3) August 2009 1 Information on the Proposed Tamakoshi 3 (TA3) Hydroelectric Project The Proponent/Developer for the project with new boundaries between SN Power is a growing international renewable Tamakoshi-Singati confl uence, and about 100 m energy company with projects in Asia, Latin upstream of the Tamakoshi bridge, at Kirnetar America and Africa. SN Power is a long-term was obtained on March 6th 2009. The TA-2 and industrial investor and is committed to social TA-3 projects have now been combined into one, and environmental sustainability throughout its i.e. the Tamakoshi 3 (TA3). The installed capacity business. The company’s current portfolio includes of the amended licence is 600 MW. hydropower projects in Nepal (Khimti Hydropower TA3 Project is located in Dolakha and Ramechhap Plant), India, the Phillipines, Sri Lanka, Chile, Peru districts. The proposed project will utilize the and Brazil. SN Power was established in 2002 fl ow of Tamakoshi River to generate electricity as a Norwegian limited company owned by by diverting the river at Betane and discharging Stratkraft, Norway’s largest utility company, and the water back into the river near Kirnetar. The Norfund, Norwegian state’s investment fund for project is under the optimization process and private companies in developing countries. In the various options are under evaluation. course of seven years, SN Power has established a strong platform for long-term growth. SN Power The project is a Peak Run-of-River (PROR) type is headquartered in Oslo, Norway. project. It is proposed to build a 102 m high dam near Betane to create a reservoir. -

Rural Vulnerability and Tea Plantation Migration in Eastern Nepal and Darjeeling Sarah Besky

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Himalayan Research Papers Archive Nepal Study Center 9-21-2007 Rural Vulnerability and Tea Plantation Migration in Eastern Nepal and Darjeeling Sarah Besky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nsc_research Recommended Citation Besky, Sarah. "Rural Vulnerability and Tea Plantation Migration in Eastern Nepal and Darjeeling." (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nsc_research/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nepal Study Center at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalayan Research Papers Archive by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rural Vulnerability and Tea Plantation Migration in Eastern Nepal and Darjeeling Sarah Besky Department of Anthropology University of Wisconsin – Madison This paper will analyze migration from rural eastern Nepal to tea plantations in eastern Nepal and Darjeeling and the potentials such migration might represent for coping with rural vulnerability and food scarcity. I will contextualize this paper in a regional history of agricultural intensification and migration, which began in the eighteenth century with Gorkhali conquests of today’s Mechi region and continued in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the recruitment of plantation laborers from Nepal to British India. For many Kiranti ethnic groups, agricultural intensification resulted in social marginalization, land degradation due to over-population and over-farming, and eventual migration to Darjeeling to work on British tea plantations. The British lured Rais, Limbus, and other tribal peoples to Darjeeling with hopes of prosperity. When these migrants arrived, they benefited from social welfare like free housing, health care, food rations, nurseries, and plantation schools – things unknown to them under Nepal’s oppressive monarchal regime. -

We Take Pride in Jobs Well Done

We take pride in jobs well done. JAGADAMBA PRESS #128 17 - 23 January 2003 16 pages Rs 25 [email protected] Tel: (01) 521393, 543017, 547018 Fax: (01) 536390 HEMLATA RAI, with JANAK NEPAL Manjushree in ○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○ NEPALGANJ hoever killed their parents, the talks to Samrat children end up in the same place. W Sangita Yadav’s father was a farmer in Leave the kids alone Banke district. The Maoists came while he was the needs of those who are already affected.” Children recruited by eating, dragged him out of his house, beat and One of the undocumented aspects of the tortured him in front of his family, and killed Maoists to carry their conflict is the growing number of internally him. Sarala Dahal’s father was a teacher in the rucksacks rest at a tea displaced families. This has increased the same district. He was killed after surrendering house in Kalikot number of children in the district headquarters, to the security forces. district in June. townships and in Kathmandu Valley who have Sarala and Sangita are both being raised in a lost their traditional village support Novelist Manjushree Thapa, author of the child shelter which has just opened in mechanisms. School closures and threats of much-acclaimed The Tutor of History has Nepalganj by the charity group, Sahara. “We forced recruitment of one child per family by a cyber-chat with fellow-author and don’t really care who killed their parents or Maoists have added to the influx of children. A compatriot, Samrat Upadhyay who has relatives, we want to protect the future of these recent survey in the insurgency hotbed of just published his second book, The Guru children, and they all get equal care here,” says Rukum alone found that out of 1,000 people of Love in the United States. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Psychosocial Intervention for Earthquake Survivors

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTION FOR EARTHQUAKE SURVIVORS FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2017 PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTION FOR EARTHQUAKE SURVIVORS Duration June 2015 to December 2016 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2015 earthquakes caused huge losses across 14 hill districts of Nepal. CMC-Nepal subsequently provided psychosocial and mental health support to affected people with funding from more than eight partners. The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) supported a major emergency mental health and psychosocial response project in Dolakha, Ramechhap and Okhaldhunga districts from June 2015 to December 2016. I would first like to thank the project team for their hard work, dedication and many contributions. The success of the project is because of their hard work and motivation to learn. I thank the psychosocial counsellors and community psychosocial worker (CPSWs) for their dedication to serving the earthquake survivors. They developed their skills and provided psychosocial services to many distressed people. I congratulate them for successfully completing their training on psychosocial counselling (for counsellors) and psychosocial support (for CPSWs) and for their courage to provide support to their clients amidst difficult circumstances. I also thank the Project’s Supervisors (Karuna Kunwar, Madhu Bilash Khanal, Jyotshna Shrestha and Sujita Baniya), and Monitoring Supervisor (Himal Gaire) for their valuable constant backstopping support to the district staff. I thank Dorothee Janssen de Bisthoven (Expat Psychologist and Supervisor) for her help to build the capacity and maintain the morale of the project’s supervisors. Dorothee made a large contribution to building the capacity of the personnel and I express my gratitude and respect for her commitment and support to CMC-N and hope we can receive her support in the future as well. -

Himalayan Linguistics a Free Refereed Web Journal and Archive Devoted to the Study of the Languages of the Himalayas

himalayan linguistics A free refereed web journal and archive devoted to the study of the languages of the Himalayas Himalayan Linguistics Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL abstract Section 1 of this paper summarizes the community-based process of Bahing orthography development. Section 2 introduces the criteria used by the Bahing community members in deciding how Bahing sounds should be represented in the proposed Bahing orthography with Devanagari used as the script. This is followed by several sub-sections which present some of the issues involved in decision-making, the decisions made, and the rationale for these decisions for the proposed Bahing Devanagari orthography: Section 2.1 mentions the deletion of redundant Nepali Devanagari letters for the Bahing orthography; Section 2.2 discusses the introduction of new letters to represent Bahing sounds that do not exist in Nepali or are not distinctively represented in the Nepali Alphabet; Section 2.3 discusses the omission of certain dialectal Bahing sounds in the proposed Bahing orthography; and Section 2.4 discusses various length related issues. keywords Kiranti, Bahing language, Bahing orthography, orthography development, community-based orthography development This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1) [Special Issue in Memory of Michael Noonan and David Watters]: 227–252. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2011. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/HimalayanLinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1). © Himalayan Linguistics 2011 ISSN 1544-7502 Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL 1 Introduction 1.1 The Bahing language and speakers Bahing (Bayung) is a Tibeto-Burman Western Kirati language, with the traditional homelands of their speakers spanning the hilly terrains of the southern tip of Solumkhumbu District and the eastern part of Okhaldhunga District in eastern Nepal. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

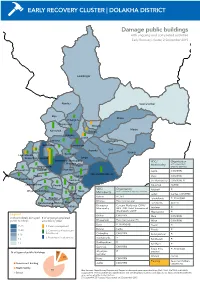

Early Recovery Cluster | Dolakha District

EARLY RECOVERY CLUSTER | DOLAKHA DISTRICT Damage public buildings with ongoing and completed activities Early Recovery cluster, 2 September 2015 Lamabagar Alambu Gaurishankar Bigu Khare Chilangkha Khopachagu Worang Marbu Kalinchok Bulung Babare Laduk Lapilang Changkhu Sundrawati Lamidanda Jhyanku Suri Syama Boch Sunkhani Lakuridanda Suspa Kshyamawati Jungu Bhimeswor Municipality VDC/ Organisation Chhetrapa Municipality with completed/ Magapauwa Kabre ongoing activities Bhusaphedi Katakuti Namdru Japhe CWV/RRN JIRI MUNICIPALITY Phasku Mirge Jhule CWV/RRN Dodhapokhari Gairimudi Jiri Municipality CWV/RRN, PI Bhirkot Sailungeshwar Pawati Kalinchok ACTED VDC/ Organisation Katakuti PI Ghyangsukathokar Jhule Hawa Municipality with completed/ongoing activities Japhe Laduk Caritas, CWV/RRN Babare ACTED Bhedpu Chyama Lakuridanda PI, RI/ANSAB Bhedpu Plan International Dandakharka Melung Malu Lamidanda ACTED Shahare Bhimeswor Concern Worldwide (CWV)/ Municipality RRN. IOM, Relief International Lapilang PI (RI)/ANSAB, UNDP Magapauwa PI Legend Bhirkot CWV/RRN Malu CWV/RRN # of completely damaged # of ongoing/completed public buildings activities by pillar Bhusaphedi Plan International (PI) Mirge CWV/RRN Boch PI, RI/ANSAB 21-28 1. Debris management Pawati PI Bulung Carita 11-20 2. Community infrastructure Phasku PI & livelihood 6-10 Chilangkha CWV/RRN Sailungeshwar PI 3. Restoration local services 3-5 Dandakharka PI Sundrawati PI Dodhapokhari PI 4% 1-2 Sunkhani PI Gairimudi CWV/RRN 12% Suspa Kshy- PI, RI/ANSAB Ghyangsu- PI amawati % of type of public buildngs 7% kathokar 14% Worang Caritas Hawa CWV/RRN Government building Planning Save the Children, Japhe CWV/RRN Government building Health facility UNDP/UNV Health facility School 79% Map Sources: Nepal Survey Department, Report on damaged government buildings, DoE, MoH, MoFALD and MoUD, 84% School August 2015. -

Open Spaces for Humanitarian Purposes in Bhimeshwor Municipality

Updated Report on 83 Open Spaces Identified for Humanitarian Purposes in Kathmandu Valley Report on Open Spaces for Humanitarian Purposes in Bhimeshwor Municipality Report on Identification and Geographical Information System (GIS) Mapping of Open Spaces for Humanitarian Purposes in Bhimeshwor Municipality 1 Chapter 1: Introduction The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an international organization, IOM acts with partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 768/12 Thirbam Sadak, Baluwatar – 5 P.O. Box 25503 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: +977-1-4426250 Fax: +977-1-4435223 Email: [email protected] Website: http://nepal.iom.int Research team: Uttam Pudasaini, Project Lead Madan Acharya, GIS Analyst Anil Kumar Mandal, Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Officer Neelam Thapa Magar, Research and Documentation Officer Yeshwant P.B. Pariyar, Graphic and Web Designer Roniksh Budhathoki, GIS Officer Sovas Tiwari, GIS Officer Editors: Louise Jönsson Andersson, IOM Nepal Tripura Oli, IOM Nepal Technical review team: Dipina Sharma Rawal, IOM Nepal Jitendra Bohara, IOM Nepal This publication has been issued without formal editing by IOM. -

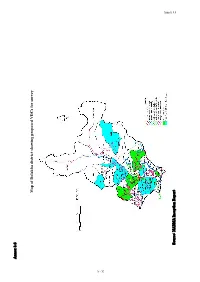

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking -

Federalism Is Debated in Nepal More As an ‘Ism’ Than a System

The FEDERALISM Debate in Nepal Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal Volume II Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal Volume II The FEDERALISM Debate in Nepal Edited by Budhi Karki Rohan Edrisinha Published by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Support to Participatory Constitution Building in Nepal (SPCBN) 2014 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Support to Participatory Constitution Building in Nepal (SPCBN) UNDP is the UN’s global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. United Nations Development Programme UN House, Pulchowk, GPO Box: 107 Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977 1 5523200 Fax: +977 1 5523991, 5523986 ISBN : 978 9937 8942 1 0 © UNDP, Nepal 2014 Book Cover: The painting on the cover page art is taken from ‘A Federal Life’, a joint publication of UNDP/ SPCBN and Kathmandu University, School of Art. The publication was the culmination of an initiative in which 22 artists came together for a workshop on the concept of and debate on federalism in Nepal and then were invited to depict their perspective on the subject through art. The painting on the cover art titled ‘’Emblem” is created by Supriya Manandhar. DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in the book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP/ SPCBN. PREFACE A new Constitution for a new Nepal drafted and adopted by an elected and inclusive Constituent Assembly (CA) is a key element of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of November 2006 that ended a decade long Maoist insurgency.