Commemoration Through Cists, Cairns and Symbols in Early Medieval Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coasts and Seas of the United Kingdom. Region 4 South-East Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 4 South-east Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1997 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, A.L. Buck, R.M. Sumerling Administration & editorial assistance J. Plaza, P.A. Smith, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice comes from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group N. Hailey English Nature Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee Prof. S.J. Lockwood Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. Pullen WWF-UK (Worldwide Fund for Nature) Dr P.C. -

Lower Largo Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

LOWER LARGO CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL and CONSERVATION AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN ENTERPRISE , PLANNING & PROTECTIVE SERVICES MCH 2012 1 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction and Purpose 1.1 Conservation Areas 1.2 Purpose of this Document 2.0 Location, History and Development 3.0 Character and Appearance 3.1 Setting 3.2 Street Pattern and Topography 3.3 Buildings and Townscape 3.3.1 Building Types 3.3.2 Distinctive Architectural Styles, Detailing and Materials 3.3.3 Orientation and Density 3.3.4 Key Listed and Unlisted Buildings 3.4 Spaces 3.5 Trees and Landscaping 3.6 Activity and Movement 3.9 Character Areas 4.0 Public Realm Audit 5.0 Negative Factors 6.0 Buildings or Other Elements At Risk 6.1 Inappropriate Materials 6.2 Replacement Windows and Doors 6.3 Buildings at Risk 7.0 Opportunities and Conservation Strategy 7.1 Boundary Refinement 7.2 Planning Policy 7.3 Long Term Management 7.4 Supplementary Planning Guidance 7.5 Article 4 Directions 8.0 Grants and Funding 9.0 Monitoring and Review 10.0 Further Advice 11.0 Further Reading Appendix 1: Conservation Area Boundary Description and Schedule of Streets within the Area Appendix 2: Listed Buildings within the Conservation Area Appendix 3: Lower Largo Proposed Article 4 Directions 2 1.0 Introduction and Purpose 1.1 Conservation Areas In accordance with the provisions contained in the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997 all planning authorities are obliged to consider the designation of Conservation Areas from time to time. Lower Largo Conservation Area is 1 of 48 Conservation Areas located in Fife. -

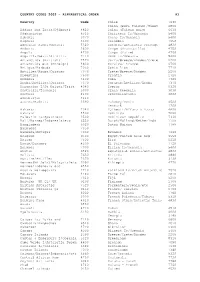

Country Codes 2002 – Alphabetical Order A1

COUNTRY CODES 2002 – ALPHABETICAL ORDER A1 Country Code Chile 7640 China (excl Taiwan)/Tibet 6800 Affars and Issas/Djibouti 4820 China (Taiwan only) 6630 Afghanistan 6510 Christmas Is/Oceania 5400 Albania 3070 Cocos Is/Oceania 5400 Algeria 3500 Colombia 7650 American Samoa/Oceania 5320 Comoros/Antarctic Foreign 4830 Andorra 2800 Congo (Brazzaville) 4750 Angola 4700 Congo (Zaire) 4760 Anguilla/Nevis/St Kitts 7110 Cook Is/Oceania 5400 Antarctica (British) 7520 Corfu/Greece/Rhodes/Crete 2200 Antarctica etc (Foreign) 4830 Corsica/ France 0700 Antigua/Barbuda 7030 Costa Rica 7710 Antilles/Aruba/Curacao 7370 Crete/Greece/Rhodes 2200 Argentina 7600 Croatia 2720 Armenia 3100 Cuba 7320 Aruba/Antilles/Curacao 7370 Curacao/Antilles/Aruba 7370 Ascension I/St Helena/Trist 4040 Cyprus 0320 Australia/Tasmania 5000 Czech Republic 3030 Austria 2100 Czechoslovakia 3020 Azerbaijan 3110 Azores/Madeira 2390 Dahomey/Benin 4500 Denmark 1200 Bahamas 7040 Djibouti/Affars & Issas 4820 Bahrain 5500 Dominica 7080 Balearic Is/Spain/etc 2500 Dominican Republic 7330 Bali/Borneo/Indonesia/etc 6550 Dutch/Holland/Netherlnds 1100 Bangladesh 6020 Dutch Guiana 7780 Barbados 7050 Barbuda/Antigua 7030 Ecuador 7660 Belgium 0500 Egypt/United Arab Rep 3550 Belize 7500 Eire 0210 Benin/Dahomey 4500 El Salvador 7720 Bermuda 7000 Ellice Is/Oceania 5400 Bhutan 6520 Equatorial Guinea/Antarctic 4830 Bolivia 7630 Eritrea 4840 Bonaire/Antilles 7370 Estonia 3130 Borneo(NE Soln)/Malaysia/etc 6050 Ethiopia 4770 Borneo/Indonesia etc 6550 Bosnia Herzegovina 2710 Falkland Is/Brtsh Antarctic -

The Kingdom of Fife

EXPLORE 2020-2021 the kingdom of fife visitscotland.com Contents 2 The Kingdom of Fife at a glance 4 A perfect playground 6 Great golf 8 Intriguing heritage 10 Outdoor adventures 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 The Kingdom of Fife is a great place to 16 Eventful Fife visit, enjoy and explore. We’ve got a 18 Travel tips wonderful coastline with award winning 20 Practical information beaches, lovely rolling countryside, and 24 Places to visit pretty villages and bustling towns. You’ll find 41 Leisure activities plenty of attractions to visit and things to do 45 Shopping whatever your interests. Explore Fife’s rich 47 Food & drink past at our historic sites and learn about our 55 Tours royal connections with the ‘In the Footsteps of Kings’ app, watch out for wildlife on the Welcome to… 58 Transport coast or in the countryside, learn about our the kingdom 59 Events & festivals heritage at one of the fantastic museums 59 Family fun (we’ve got everything from golf to fishing!), of fife 60 Accommodation bring your golf clubs and play world famous 68 Regional map courses, discover the vibrant arts and culture You’ll never forget the Kingdom of Fife. Explore this enchanting region and you’ll take back memories of gorgeous coastal villages, scene including some amazing artists, ancient castles, a royal palace and historic abbeys, as well as makers and musicians, visit iconic film and relaxing times enjoying delicious food and drink. Tee off in the TV locations, or try something different like spiritual home of golf, dig your toes into the sand on swimming with sharks or creating your own award-winning beaches and soak up historic tales. -

The Roundel, Lundin Links, Leven, Fife

The Roundel, Lundin Links, Leven, Fife Stewart Filshill Offers Over £185,000 The Roundel, Lundin Links, Leven, Fife Offers Over £185,000 DESCRIPTION This semi detached villa should be viewed to see the fantastic DIMENSIONS floor space created by the rear extension. The property occupies a favourable position within a sought after residential Lounge development with an open outlook to the front onto a grass 4.71m x 3.31m (15'6" x 10'10") verge. The accommodation comprises, entrance hall, lounge, large open plan kitchen/dining/family room, ground floor WC, Kitchen/Dining/Family Room three bedrooms (master ensuite) and shower room. The 6.92m x 4.58m (22'8" x 15'0") property has landscaped gardens to the front and rear. A drive provides off street parking and leads to the garage. The Master Bedroom specification includes double glazing and gas central heating. 5.02m x 2.60m (16'6" x 8'6") LOCATION Bedroom This development is established and highly sought after 3.36m x 3.40m (11'0" x 11'2") encompassing a range of semi and detached property types. Bedroom The Crusoe Hotel and Railway Inn Tavern are approx 800 3.12m x 2.35m (10'3" x 7'9") metres away down Harbour Wynd at the shore front in Lower Largo. Among the many attractions of Lundin Links and the East Neuk are the numerous golf courses and picturesque fishing villages. Lundin Links has a beautiful links golf course which has previously been used for qualifying to the open golf championship. There is also a 9 hole ladies golf course. -

Whin Cottage, 1 Hillhead Lane, Lundin Links, Fife, KY8

Whin Cottage, 1 Hillhead Lane, Lundin Links, Fife, KY8 6DE 01592 803 400 | WWW.THORNTONS-PROPERTY.CO.UK Nestled in the charming and sought-after East Neuk village of Lundin Links, just minutes’ walk from its scenic sandy beach, this historic end-terraced stone-built cottage with an architect-designed extension and views towards the seafront and the rugged Largo Law, offers the perfect blend of character and contemporary living. Incorporating two storeys of accommodation, the cottage exudes a welcoming airy ambience created by large, contemporary windows, many south-facing, and stylish neutral interiors harmonised with warm natural wood finishes. Currently set up as a two- reception room plus a large multi-functional bedroom, the versatile layout can also accommodate two bedrooms and one reception room. Positioned behind a delightful garden and rustic stone walling, the cottage opens into a wonderfully in neutral tones, the bathroom comprises a WC-suite and a shower-over-bath. An impressive bright sun porch featuring useful cloakroom storage. From here, you step into an open-plan central cantilevered spiral staircase, lit by a spectacular feature window with sea views, leads to the first hallway giving access to all the ground-floor accommodation, and a spiral staircase leading to the floor. Here, a master bedroom extends the full width of the property and is bathed in sunny natural first floor. Situated on either side of the hallway are two generous reception areas; a formal dining light from numerous dual-aspect skylight windows. Also benefiting from extensive built-in room (featuring atmospheric dimmer lighting and also ideal for use as a second double bedroom) storage, this vast space is divided into two areas, with a bedroom flowing through to large and a dual-aspect living room, both flanking an open-plan design to a modern, fitted kitchen. -

18 Emsdorf Street LUNDIN LINKS, KY8 6AB 01333 400 400 18 Emsdorf Street LUNDIN LINKS, KY8 6AB

18 Emsdorf Street LUNDIN LINKS, KY8 6AB 01333 400 400 18 Emsdorf Street LUNDIN LINKS, KY8 6AB The area around Lundin Links, which is linked to the history, with castle, cathedral and former abbey, village of Lower Largo, boasts an excellent range of now a private school. countryside, from rolling hills and pasture to miles of coastline and pretty East Neuk villages. It takes only Lundin Links is 30 miles from Perth and 38 miles 5 minutes to walk from 18 Emsdorf Street to the from Edinburgh, with railway stations nearby at beach at the fishing village of Lower Largo. Cupar, Markinch, Leuchars and Kirkcaldy. The village has a primary school, pharmacy, butcher/ Fife offers an excellent selection of restaurants baker, grocer and other local shopping facilities. and places to eat, serving award-winning local produce. It is renowned as one of Scotland’s most Lower Largo is the home of Alexander Selkirk, magnificent and inspiring areas, providing something portrayed as the fictional Robinson Crusoe in for everyone; whether that is enjoying adventure Daniel Defoe’s novel of the same name. A statue and exploration, relaxation, nature or history. It is of Robinson Crusoe is erected on the site of the extremely popular with holiday makers from all over home of Alexander Selkirk. Not far from the the world. There are many holiday homes here. The statue is the well-known Largo Bay Sailing Club, area offers complete escapism. In addition to its which attracts sailors from all over. The Crusoe variety of wildlife, there is a vast range of outdoor Hotel is situated by Largo pier and offers a bistro, pursuits available in this part of Fife, including walking, restaurant, pub and accommodation. -

The Soils of the Country Round Fife and Kinross (Sheets 40 – Kinross and Parts of 41 – Elie and 32 – Edinburgh)

Memoirs of the Soil Survey of Scotland The Soils of the Country round Fife and Kinross (Sheets 40 – Kinross and parts of 41 – Elie and 32 – Edinburgh) By D. Laing (Ed. J.S. Bell) The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen 2016 Contents Chapter Page Preface vi Acknowledgements vi 1. Description of the Area 1 Location and Extent 1 Physical Features 1 Climate 7 2. Geology and Soil Parent Materials 12 Geology 12 Parent Materials 15 3. Soil Formation, Classification and Mapping 25 Soil Formation 25 Soil Classification 29 Soil Mapping 35 4. Soils 36 Introduction 36 Balrownie and Forfar Associations 39 Carpow Association 40 Carpow Series 40 Darleith Association 42 Darleith Series 42 Drumain Series 44 Dunlop Series 46 Cringate Series 47 Baidland Series 47 Amlaird Series 49 Myres Series 51 Pilgrim Complex 53 Skeletal Soils 53 Darvel Association 54 Darvel Series 54 Duncrahill Series 56 Dreghorn Association 58 Dreghorn Series 58 Quivox Series 60 Eckford Association 62 Hexpath Series 62 Kilwhiss Series 64 i Giffordtown Series 66 Woodend Series 68 Fraserburgh Association 70 Fraserburgh Series 70 Giffnock Association 72 Aberdona Series 72 Giffnock Series 74 Scaurs Series 76 Forestmill Series 77 Kennet Series 79 Devilla Series 82 Bath Moor Series 83 Ponesk Series 84 Gleneagles Association 86 Gleneagles Series 86 Hindsward Association 90 Reidston series 90 Hindsward Series 92 Polquhairn Series 93 Dumglow Series 95 Kippen Association 98 Urquhart Series 98 Fourmerk Series 100 Kilgour Series 102 Kippen Series 102 Butterwell Series 104 Redbrae Series 107 Skeletal -

Play Spaces Strategy Proposal Maps Levenmouth

Let’s talk Playabout spaces in the Levenmouth Area Ward 21 Ward 22 Leven, Kennoway Buckhaven, Methil And Largo And Wemyss Villages Kennoway, Methil, Windygates, Buckhaven, Leven, East Wemyss, Lundin Links, Coaltown of Wemyss, Lower Largo, West Wemyss, Upper Largo Photograph courtesy of Play July 2019 Scotland introduction From 21st August and 10th December 2019, you can take part in our discussion on the future of play spaces. Play spaces include equipped play parks, greenspace with play features (e.g slopes for sliding, logs for climbing on), and greenspaces for playing in, (e.g parks and woods). We are looking at the future of Fife Council play spaces. We need a long term plan as there are a number of issues with play spaces. Most of the play equipment will be at the end of its safe use in the next ten years. Many of the play parks can only be used by children under the age of 5. Fife Council has a draft Play Spaces Strategy to address these challenges. If the Council approve the strategy, it will: • be used to secure funding for upgrading play parks, • ensure play parks have a range of equipment that can be used by all ages of children • transform many greenspaces into play spaces After the let’s talk discussion, a report will be compiled. This will be used to aid councillors on approving the strategy. In this report you will find our proposal maps for Fife Council play spaces for towns and villages in South & West Fife. We have not included proposals for play equipment in school grounds or maintained by housing factors or housing associations. -

Largo Serpentine

Largo Serpentine Largo Serpentine Management Plan 2017-2022 Largo Serpentine MANAGEMENT PLAN - CONTENTS PAGE ITEM Page No. Introduction Plan review and updating Woodland Management Approach Summary 1.0 Site details 2.0 Site description 2.1 Summary Description 2.2 Extended Description 3.0 Public access information 3.1 Getting there 3.2 Access / Walks 4.0 Long term policy 5.0 Key Features 5.1 Informal Public Access 5.2 Long Established Woodland of Plantation Origin 6.0 Work Programme Appendix 1: Compartment descriptions Glossary MAPS Access Conservation Features Management 2 Largo Serpentine THE WOODLAND TRUST INTRODUCTION PLAN REVIEW AND UPDATING The Trust¶s corporate aims and management The information presented in this Management approach guide the management of all the plan is held in a database which is continuously Trust¶s properties, and are described on Page 4. being amended and updated on our website. These determine basic management policies Consequently this printed version may quickly and methods, which apply to all sites unless become out of date, particularly in relation to the specifically stated otherwise. Such policies planned work programme and on-going include free public access; keeping local people monitoring observations. informed of major proposed work; the retention Please either consult The Woodland Trust of old trees and dead wood; and a desire for website www.woodlandtrust.org.uk or contact the management to be as unobtrusive as possible. Woodland Trust The Trust also has available Policy Statements ([email protected]) to confirm covering a variety of woodland management details of the current management programme. -

Over the Years the Fife Family History Society Journal Has Reviewed Many Published Fife Family Histories

PUBLISHED FAMILY HISTORIES [Over the years The Fife Family History Society Journal has reviewed many published Fife family histories. We have gathered them all together here, and will add to the file as more become available. Many of the family histories are hard to find, but some are still available on the antiquarian market. Others are available as Print on Demand; while a few can be found as Google books] GUNDAROO (1972) By Errol Lea-Scarlett, tells the story of the settlement of the Township of Gundaroo in the centre of the Yass River Valley of NSW, AUS, and the families who built up the town. One was William Affleck (1836-1923) from West Wemyss, described as "Gundaroo's Man of Destiny." He was the son of Arthur Affleck, grocer at West Wemyss, and Ann Wishart, and encourged by letters from the latter's brother, John (Joseph Wiseman) Wishart, the family emigrated to NSW late in October 1854 in the ship, "Nabob," with their children, William and Mary, sole survivors of a family of 13, landing at Sydney on 15 February 1855. The above John Wishart, alias Joseph Wiseman, the son of a Fife merchant, had been convicted of forgery in 1839 and sentenced to 14 years transportation to NSW. On obtaining his ticket of leave in July 1846, he took the lease of the Old Harrow, in which he established a store - the "Caledonia" - and in 1850 added to it a horse-powered mill at Gundaroo some 18 months later. He was the founder of the family's fortunes, and from the 1860s until about 1900 the Afflecks owned most of the commercial buildings in the town. -

Levenmouth Brochure

Visitor Guide Fife’s Energy Coast 1 “Stand on Leven beach and turn your head 360 degrees while you’re enjoying the white sand there. Revitalise your spirit Watch the light pour Fife’s Energy Coast stretches from the Wemyss conservation down from the north villages, famous for their caves and pottery, to the spectacular sea vistas of Largo Bay where the real Robinson Crusoe first felt sand over the Lomonds, between his toes. Along almost 20 kilometres of coastline you watch it come up can energise yourself with walks, golf and numerous activities, or with the sun from simply recharge your batteries strolling around fascinating towns the North Sea in the and villages. east. Share it with Fife’s Energy Coast has a great industrial past and is now a world- Edinburgh and the leading centre for renewable energy with cutting edge technology opposite coast in the that places it at the forefront of global efforts to develop green energy from sustainable sources. south and watch it burn the sky as it sets Its friendly, forward-looking communities are renowned for their in the west towards energetic focus on enhancing the health and wellbeing of local residents who can enjoy Fife’s great outdoors 365 days a year. Glasgow. Enjoy it. Lap it up, it’s the best With Edinburgh across the water to the south and St Andrews just to the north, Fife’s Energy Coast is ideally located to explore light in the UK and it the beautiful coastlines, rich heritage, family-friendly attractions will show you Fife in and wide open countryside of the Kingdom of Fife.