The Making of Cheap Labour Power: Nokia's Case in Cluj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Transplant Centre and Medical Research Centre The

INTEGRATED TRANSPLANT CENTRE AND MEDICAL RESEARCH CENTRE Other information: Type of project: Integrated project • Regional Transplant Centre - multidisciplinary level Ownership type: Public Type of partnership: International Design Contest • Medical Research Centre Location: Cluj-Napoca • Health Rehabilitation Unit Cost of the investment: 5 Mio EUR • Heliport Land surface: 6,800 sq.m THE MONO BLOC CHIldren’s HOSPITAL Type of project: Infrastructure for healthcare Ownership type: Public / Public-Private Type of partnership: Public procurement Location: Cluj-Napoca Cost of investment: 50 Mio EUR Built area: 5 hectares Capacity: 506 beds for children and 150 for attendants. www.cjcluj.ro REMODELING THE ETNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM OF TRANSYLVANIA Administration Centre of the National National Etnographic Park ”Romulus Vuia” Etnographic Park ”Romulus Vuia” Visitor Centre of the National Etnographic Activity Hub of the National Park ”Romulus Vuia” Etnographic Park ”Romulus Vuia” Forest-Park Hoia Industrial Park Tetarom I GSPublisherVersion 0.0.100.12 Type of project: Integrated project Ownership type: Public Type of partnership: Public / Private Location: Cluj-Napoca Cost of the investment: 11 Mio EUR Site area: 420,000 sq.m Other information: • Multifunctional art & leisure - 365 days of activities • Conference halls • Visitor Centre - a cluster of buildings organised like a • Open-air stage traditional settlement: main market street, souvenir street, • Forest area and Parc Hoia Rehabilitation main event square, rain garden, winery courtyard • Leisure -

Presentation Innovation Seminar

1 2 Dealurile Clujului Est learning area (LA) is located in the North-Western Romanian Development region (Map 1). The site is situated in the middle of the Romanian historical region of Transylvania that borders to the North-East with Ukraine and to the West with Hungary (Map 2). 3 Administratively, the study area is divided into eight communes (Apahida, Bonțida, Borșa, Chinteni, Dăbâca, Jucu, Panticeu and Vultureni) that are located in the peri-urban area of Cluj - Napoca city (321.687 inhabitants in 2016). It is the biggest Transylvanian city in terms of population and GDP per capita (Map 3). A Natura 2000 site is the core of the LA, and has the same name (Map 4). The LA boundaries were set to capture the Natura 2000 site plus surrounding farmland with similar nature values. The study area also belongs to several local administrative associations. With the exception of two communes (Panticeu and Chinteni), the territory appertains to the Local Action Group (LAG) Someș Transilvan. Panticeu commune is member of Leader Cluj LAG and Chinteni commune currently belongs to no LAG (Map 3). This situation brings inconsistences in terms of good area management. All administrative units, with the exception of Panticeu, belong to the Cluj-Napoca Metropolitan Area. Its strategy acknowledged agriculture as a key objective. Also, it is previewed that the rural areas around Cluj-Napoca can be developed by promoting local brands to the urban consumers and by creating ecotourism facilities (Cluj- Napoca Metropolitan Area Strategy, 2016). The assessment shows that future HNV innovative programmes have to be incorporated in all these local associative initiatives. -

REFERENDUM in ROMANIA 29Th July 2012

REFERENDUM IN ROMANIA 29th July 2012 European Elections monitor Romanian President Traian Basescu avoids impeachment once again Corinne Deloy Five years after 17th April 2007, when the first referendum on his impeachment as head of State took place, Traian Basescu, President of the Republic of Romania again emerged victorious in the Results battle that opposed him, this time round, against Prime Minister Victor Ponta (Social Democratic Party, PSD). A majority of Romanians who were called to vote for or against the impeachment of the Head of Sate indeed stayed away from the ballot boxes on 29th July. Only 46.13% of them turned out to vote whilst turn out of at least half of those registered was necessary for the consultation to be deemed valid. The government made an attempt to abolish this threshold that has been part of the electoral law since 2010, before being reprimanded by the European Commission and other Western leaderships. Victor Ponta did do everything he could however to achieve the minimum turnout threshold by leaving the polling stations open for four hours more than is the custom (7am to 11pm) and by opening fifty other stations in hotels and restaurants on the shores of the Black Sea where some Romanians spend their holidays. “The Romanians have rejected the coup d’Etat “Whatever the final turnout is no politician can deny launched by the 256 MPs and led by Prime Minister the will of millions of voters without cutting himself Victor Ponta and interim President Crin Antonescu. The off from reality,” declared Prime Minister Ponta. -

CSV Concesionata Adresa Tel. Contact Adresa E-Mail Medic Veterinar

CSV Adresa Tel. Contact Adresa e‐mail Medic veterinar Concesionata Loc. Aghiresu nr. 452 A, Dr. Muresan 1 Aghiresu 0731‐047101 [email protected] com. Agiresu Mircea 2 Aiton Loc. Aiton nr. 12 0752‐020920 [email protected] Dr. Revnic Cristian 3 Alunis Loc. Alunis nr. 85 0744‐913800 [email protected] Dr. Iftimia Bobita Loc. Apahida 4 Apahida 0742‐218295 [email protected] Dr. Pop Carmen str. Libertatii nr. 124 Loc. Aschileu Mare nr. florinanicoletahategan 5 Aschileu 0766‐432185 Dr. Chetan Vasile 274, com. Aschileu @yahoo.com Loc. Baciu 6 Baciu 0745‐759920 [email protected] Dr. Agache Cristian str. Magnoliei nr. 8 0754‐022302 7 Baisoara ‐ Valea Ierii Loc. Baisoara nr. 15 [email protected] Dr. Buha Ovidiu 0745‐343736 Loc. Bobalna nr. 35, 8 Bobalna 0744‐763210 [email protected] Dr. Budu Florin com. Bobalna moldovan_cristianaurelian Dr. Moldovan 9 Borsa Loc. Borsa nr. 105 0744‐270363 @yahoo.com Cristian 10 Buza Loc. Buza nr. 58A 0740‐085889 [email protected] Dr. Baciu Horea 11 Caian Loc. Caianu Mic nr. 18 0745‐374055 [email protected] Dr. Tibi Melitoiu Loc. Calarasi nr. 478A, 12 Calarasi 0745‐615158 [email protected] Dr. Popa Aurel com. Calarasi. 13 Calatele ‐ Belis Loc. Calatele nr. 2 0753‐260020 Dr. Gansca Ioan 14 Camaras Loc. Camaras nr.124 0744‐700571 [email protected] Dr. Ilea Eugen Loc. Campia Turzii Dr. Margineanu 15 Campia Turzii 0744‐667309 [email protected] str. Parcului nr. 7 Calin Loc. Capus str. 16 Capus 0744‐986002 [email protected] Dr. Bodea Radu Principala nr. 59 17 Caseiu Loc. -

Lista Medici De Familie

DSP CLUJ- LISTA MEDICI DE FAMILIE Nr.crt. NUME MEDIC de FAMILIE urban rural Localitate Adresa Nr.Telefon FELEACU STR. PRINCIPALA NR.146, GHEORGHIENI 0743-188657 1 Ardelean Emanuela x GHEORGHIENI VALCELE 76, VALCELE STR PRINCIPALA NR. 158 E 2 Bakri Camelia x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. GALAXIEI NR.13 0264-443384 3 Blaga Gabriella/ Miftode Alexandra x CLUJ-NAPOCA B-DUL 21 DECEMBRIE 1989 NR.49 0264-592144 4 Benta Marinela x GHERLA STR. GEORGE COSBUC NR.7 AP. 4 0264-244345 5 Bondric Aura Doina x MINTIU GHERLII NR.411 0264-241772 6 Bora Mihaela Narcisa x DEJ STR. CLOSCA NR.2 0264-214867 7 Calin Anamaria x GHERLA STR.1 DECEMBRIE 1918 NR.3 AP.I si II 0264-241788 8 Calugar Nadina Ioana x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR.PASTEUR NR.58 0264-524005 9 Chira Emanuil x Com MICA STR. PRINCIPALA NR.210 0724-744188 10 Chisiu Minodora x TURDA STR.ANDREI MURESANU NR.22 0264-311498 11 Chendrean Maria-Daniela x APAHIDA STR.HOREA NR.17 0264-232393 12 Chkess Liliana x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. IZLAZULUI NR.18 0733-066250 13 Circa Viorel Octavian x CIURILA NR. 11 AP.2 0745-868080 14 Cojan Manzat Bianca x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. GODEANU NR.12 AP.51 0364-268044 15 Corpadean Otilia x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. PASTEUR NR.60 0264-522111 16 Cristurean Alina x CAMPIA TURZII STR. AVRAM IANCU NR. 33 0264-366165 17 Csergo Marta Eniko x CAMPIA TURZII STR.AVRAM IANCU NR.33 0264-365400 18 Dascal Corina x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. GR.ALEXANDRESCU NR.5 0264-486707 19 Dascal Nicolae x CLUJ-NAPOCA STR. -

Aerodrome Elev. Rwy 26 Ils/Dme Cluj-Napoca

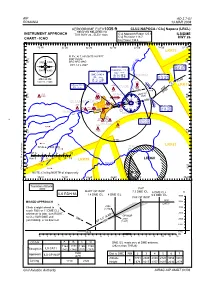

AIP AD 2.7-51 ROMANIA 13 MAR 2008 AERODROME ELEV.1035 ft CLUJ-NAPOCA / Cluj Napoca (LRCL) HEIGHTS RELATED TO INSTRUMENT APPROACH THR RWY 26 - ELEV 1023 Cluj Approach/Radar 125.1 ILS/DME Cluj Precision 118.7 RWY 26 CHART - ICAO Cluj Tower 134.4 23˚10’ 23˚20’ 23˚30’ 23˚40’ 23˚50’ 24˚00’ 24˚10’ LRR70 ELEV, ALT, HEIGHTS IN FEET 47˚ DIST IN NM ic 47˚ M 00' 3700 3300 BRG ARE MAG l 00' u s BARTA VAR 3.4˚E 2007 e CLUJ 46˚54’ 25"N m o 24˚05’ 22"E DVOR/DME 111.2 S 7900 4300 CLUJ CLJ DME CH 40 X 46˚ 48’ 00"N BONTIDA MAGEL ICL 23˚ 47’ 14"E 46˚52’ 43"N 23˚54’ 46"E MSA 25 NM 46˚ 47’ 14"N from CLJ VOR 23˚ 41’ 36"E 1489 7 NM FL50 CLJ 8 ILS/LLZ 110.3 1974 LRR71 ICL JUCU DE JOS (466) (951) 075˚ 1808 3500 46˚ 2628 2296 APAHIDA MNM ALT 46˚ 50' (1605) 1354 0 3500 50' (1273) (331) 1593 1702 1079 255˚ 6 NM CLUJ-NAPOCA 9 CLJ 2089 27 (679) (570) NEGUR 2030 1821 1710 (56) 18 46˚49’ 17"N (1007) (798) 23˚55’ 46"E GILAU (1066) 255˚ (687) DEZMIR 1788 3236 2640 (2213) FAP (1617) 2519 46˚48’ 34"N 23˚52’ 03"E 2728 FELEACU 4049 (1496) 46˚ 46˚ (1705) 40' 40' 10 NM 4700 LRR81 SCALE 1:500 000 TURDA 4843 NM 0 2 4 6 8 10 Km 0 3 6 912 15 18 LRR75 LRD60 5656 Ariesul 46˚ 5765 46˚ 30' 5991 30' Changes: New obstacles NOTE: Circling NORTH of airport only LRD03 23˚10’ 23˚20’ 23˚30’ 23˚40’ 23˚50’ 24˚00’ 24˚10’ Transition Altitude 4000 FAP MAPT GP INOP 7.3 DME ICL 6 DME CLJ ft ILS RDH 56 1.4 DME ICL 4 DME ICL 9.9 DME ICL 4000 FAF GP INOP 3500 MISSED APPROACH 3500 (2477) 2359 3000 Climb straight ahead to (1336) reach 3500 or 11 DME CLJ whichever is later, turn RIGHT, 2500 GP INOP to CLJ VOR/DME and 255˚ join holding, or as directed. -

Narancs Arial 10

T R A V E L G U I D E SomesL o c a l A Transilvanc t i o n G r o u p T r a n s y l v a n i a L o c a t i o n a n d p o p u l a t i o n The Local Action Group (from now on LAG) Someș Transilvan territory is identified in the North-West region of Romania, in Cluj County, in the Eastern part of Cluj-Napoca Municipality and includes the North - East of it, at the crossroads of two major units of relief: the Somesan Plateau in the West and the Transylvania Plain in the East, and from the South to North it is crossed by the river Somesul Mic. The territory consists of 14 communes (comună in Romanian - is the lowest level of administrative subdivision in Romania): Aluniş, Apahida, Bonţida, Borșa, Bobâlna, Cornești, Dăbâca, Jucu, Iclod, Mintiu Gherlii, Recea Cristur, Vultureni, Sic and Gîrbou commune from Salaj County, the entire territory of the LAG covering 85 villages.The territory is in an interference area of two major relief units: the Transylvanian Plain and Somes Plateau separated by the valley corridor of Somesul Mic, major traffic axis. Total population consists of 43,141 inhabitants with a density over the entire area of 41.15 inhabitants/km².On the entire discussed territory the population is characterized as being a multicultural one: Romanians, Hungarians, Roma and a lower percentage of Germans. Confessions are: Orthodox, Protestant, Pentecostal, Greek Catholic, Baptist, Someșul Mic river Adventist and Roman Catholic. -

Lista Cabinete Asistenta Medicala Primara

FURNIZORI DE SERVICII MEDICALE DIN ASISTENTA MEDICALA PRIMARA Aprilie 2015 Nr Denumire furnizor Nr Medic Localitate Adresa Telefon Fax E-mail Perioada contractului Crt asistenta medicala primara contract 1 CABINET MEDICAL " AGHIRES MED" LUP LETITIE Com AGHIRESU STR. PRINCIPALA NR. 203 0755-662471 [email protected] 244 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA DE 2 FAMILIE MARGAUAN LAURA-IOANA Com AGHIRESU STR. PRINCIPALA NR. 203 0741-646260 [email protected] 470 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA DE 3 FAMILIE RUS MIRELA-MARIA Com AGHIRESU STR.PRINCIPALA, NR.203 0264-357329 0745-053835 [email protected] 475 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 4 CABINET MEDICAL " AGHIRES MED" ZAHARIA ANGELA Com AGHIRESU STR. PRINCIPALA NR. 203 0264-357098 0745-517809 [email protected] 273 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL MEDICINA DE 5 FAMILIE PASCAL DANIELA MIHAELA Com AITON NR.159A 0372-727992 [email protected] 526 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA DE 6 FAMILIE MIRONESCU CLAUDIU-COSMIN Com ALUNIS NR. 181 0763-845226 [email protected] 469 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA DE 7 FAMILIE CHENDREAN MARIA-DANIELA Com APAHIDA STR. HOREA NR.18 0264-232393 [email protected] 409 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA 8 GENERALA - MEDICINA DE FAMILIE LOGA DRAGOMIR SIMONA Com APAHIDA STR. HOREA NR.18 0264-231587 [email protected] 23 01.07.2014-30.04.2015 CABINET MEDICAL DE MEDICINA 9 GENERALA - MEDICINA DE FAMILIE PETRINA NICOLETA Com APAHIDA STR. -

Irony and Violence in Political Language

DISCOURSE AS A FORM OF MULTICULTURALISM IN LITERATURE AND COMMUNICATION SECTION: SOCIOLOGY, POLITICAL SCIENCES AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ARHIPELAG XXI PRESS, TÎRGU MUREȘ, 2015, ISBN: 978-606-8624-21-1 IRONY AND VIOLENCE IN POLITICAL LANGUAGE Bianca Drămnescu PhD Student, West University of Timișoara Abstract: This paper inquires elements of irony and violence in politicians language. This topic plays an important role in the behavior of voters. In the opinion of philosopher Quintilian irony represents “ the process to say the opposite of what you want to understand” (Quintilian 1974:36). Language is a form of manipulation of public opinion. Including ironies and violence aspects in political language may disturb sensitive people that can not accept “dirty games”. Words expressed against political leaders can affect the image of Romania. Also, violence in language may cause conflicts between countries. The situation that affected the most voters behavior occurred in the winter of 2012 when, across the country, they held street protests against government. Those protests had a political character carried out in order to to remove the current government. In the end people’s power won and the Prime Minister was removed. In this study I want to make a comparison between the reaction of romanian and international politicians according to the irony and violence in language during protests. The principle of violence and irony in language applies to every political protest. In this case people do not protest a simple reality, they express feelings, experience through language. Keywords: irony, violence, language, protests, image. In different situations the way we speak can reveal something about what we intend to do in action. -

Reabilitarea Teritorială La Nivel Regional Şi Local

ROMANIAN REVIEW OF GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION Volume VII, Number 2, August 2018 pp. 23-30 DOI: http://doi.org/10.23741/RRGE220182 PRESCHOOLERS’ EXPLORATION OF HERB ENVIRONMENTS VIORICA-ADELA BRUDAN Normal Programme Kindergarten, Iclandu Mare, Mureș County, Romania, e-mail: [email protected] RALUCA-CLAUDIA CASSIANU Gymnasium School Tureac, Bistrița-Năsăud County; Babeş-Bolyai University, Faculty of Psychology and Sciences of Education, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, e-mail: [email protected] (Received: March 2018; in revised form: May 2018) Abstract The present study is about a description of an experimental research, realised in 2016-2017 school year, at the Normal Programme Kindergarten in Iclandu Mare, Mureș County, Romania. The following hypothesis was tested: If preschoolers are systematically involved in direct exploration activities of the environment with low herbs associations, then, they acquired a big volume of knowledge about this type of environment and they develop their thinking operations. In this psycho- pedagogical experiment, it was applied an initial test, many learning activities were organized in a rural area, where the preschoolers studied the herb environments (pastures, grassland, meadows) and, in the end, it was applied another test. The preschoolers’ registered results from the experimental group showed that the structured learning activities by Exploration-Explanation-Extension model were effective and the preschoolers have acquired a lot of knowledge compared to the initial stage. In this research, the hypothesis was confirmed. Keywords: hike, activity in nature, observation, sensory games, field activity INTRODUCTION The grass represents a generic name assigned to annual or perennial herbaceous plants, with green and thin airlines, which are used as animal feed (DEX, 2009). -

List of Issues Concerning Romania for Consideration

LIST OF ISSUES CONCERNING ROMANIA FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE COMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS AT ITS PRE-SESSIONALWORKING GROUP FOR THE 53 RD SESSION (MAY 26-30, 2014) 28 MARCH 2014 Dear Sir/Madam, The European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) 1 respectfully submits a list of issues concerning Romania for consideration by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) at its pre- sessional Working Group for the 53 rd Session, which will be held from 26 th to 30 th May 2014. The ERRC has undertaken regular monitoring of the human rights situation of Roma in Romania, and this list of issues reflects the current priorities of the submitting organisation in its work in Romania. INTRODUCTION According to current unofficial estimates Roma in Romania make up approximately 9% of the population (approximately 1,700,000). However, a verified and accurate count remains elusive. 2 According to the final results of the 2011 Census of the Population and Households published on 4 July 2013 by the National Statistics Institute, Romania had a total population of 20.12 million. Among the 18.88 million respondents who self-reported their ethnicity, 621,600 were Roma (3.3%, an increase from 2.46% in the 2002 census). 3 The ERRC’s research on Roma in Romania 4 shows that Roma continue facing discrimination in all areas of social life, including housing, education, employment and health. In December 2011, the Romanian Government adopted the Strategy for the Inclusion of the Romanian Citizens belonging to Roma minority for the period 2012 – 2020 5 in the context of the European Commission’s Communication on adopting an EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020 6 (hereinafter the Strategy). -

Romania – to Have Or Not to Have Its Own Development Path?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bodea, Gabriela; Plopeanu, Aurelian-Petrus Article Romania – to have or not to have its own Development Path? CES Working Papers Provided in Cooperation with: Centre for European Studies, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University Suggested Citation: Bodea, Gabriela; Plopeanu, Aurelian-Petrus (2016) : Romania – to have or not to have its own Development Path?, CES Working Papers, ISSN 2067-7693, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Centre for European Studies, Iasi, Vol. 8, Iss. 2, pp. 221-237 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/198458 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu CES Working Papers – Volume VIII, Issue 2 ROMANIA – TO HAVE OR NOT TO HAVE ITS OWN DEVELOPMENT PATH? Gabriela BODEA* Aurelian-Petrus PLOPEANU** Abstract: Human societies are evolving in sequences similar to a business cycle.