Aw for Game Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abcors Abchronicle No 37

Trademarks Ban on name change to TOM Volume 12 • ISSUE 37 • OCT 2019 2016 2013 Kreativn Dogadaji vs Hasbro: bad faith repeated filing MONOPOLY Iron Maiden Holdings vs 3D Realms: Game renamed to Ion Fury A Dutch chain of petrol stations has slogan "TOM HELPS YOU DISCOVER Brazil: cheaper trademark application been using a fictional character NEW ROADS" is used. This use is in via the International Registration named “Tom de Ridder” in its radio conflict with the agreement, so commercials since 2009, in order to TomTom protests. Parties end up in Constantin Film: Fack Ju Göthe public promote its payment card and court. By provisional ruling the use of policy and principles of morality parking services. In 2015, the the name is prohibited. In appeal the company decides to change the name court comes to the same conclusion. Petsbelle vs EBI: novelty and to TOM. To prevent problems, the The agreement has been rightfully promotional video on Facebook company discusses the plans with dissolved by TomTom. Since an TomTom (the well known car agreement no longer exists, any use of navigation brand). The TOM logo is the logo or word mark constitutes an MVSA vs Invert: Shoebaloo shoe modified and a coexistence infringement. TomTom is a well-known wall is a creation agreement signed. In this agreement brand and TOM is similar. Navigation it is stated that only the logo shall be and (travel) information equipment La Paririe vs Lidl: misleading used and not the word TOM. No are complementary or at least similar advertising and own press release provisions are made for the use of to mobility services and travel TOM as a trading name. -

Blood Engines Free Ebook

FREEBLOOD ENGINES EBOOK T.A Pratt | 338 pages | 25 Sep 2007 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553589986 | English | New York, United States Daemon Engine | Warhammer 40k Wiki | Fandom While urban fantasy isn't Blood Engines usual thing, I'd previously read The Strange Adventures of Rangergirl and liked it, so I figured why not dive into another series by the same author? Blood Engines I definitely enjoyed Blood Enginesthere were parts I could have done without, and what really bothered me the most is that for all Mason's purported and often spoken of ability to kick butt, she never really does. Blood Engines begins in San Francisco Pratt makes his home in Oakland, just on the other side of the bay; I grew up in the Bay Area, so I'm more than a little familiar with the lay of the land where Marla Mason has come in search of a Cornerstone, an ancient magical device whose power Blood Engines to enhance and make permanent the effects of any spell. Mason hopes to work some magic to defeat a rival back in her own city of Felport. A wrench is Blood Engines into her plans when the contact she'd come to connect with, and who also knew the location of the Cornerstone, is murdered. Blood Engines obligated to seek out the murderer, and because that path also intersects with her own immediate goal, Mason sets out to bring the perpetrator to her sort of justice. Pratt is a deft storyteller. The writing is crisp and doesn't waste the reader's time with loads of info dumps. -

Fury Unleashed Full Crack Addonsl

Fury Unleashed Full Crack [addons]l Fury Unleashed Full Crack [addons]l 1 / 4 2 / 4 Mods, Addons & Total Conversions ... CENTCOM | Demon Rage | Frostbite | Heroes Unleashed | Year of the Monkey ... Babylon 5 Star Fury Pilot | The Earth Brakiri War ... With the SimCopterX patcher, you can patch your game to work natively on ... In this mod featuring full HDR, you play the role of Jamil Lee who is a young .... of Ekrund are united in slow, cold fury and the rock itself rang from their ... To fight more efficiently there are two basic Addons EVERY Dwarf must use. ... http://www.ror.builders/career/ironbreaker/s?l=40&r=60&tl=4&mp= ... Situational: Grudge Unleashed, Furious Reprisal, Away with Ye, ... skulls to crack.. Click the link below to read the full Patch Notes ... Maître de l'évasion's cooldown has been reduced to 1 minute (down from 1.5 minutes). ... and the skill ceiling is so high that few can reach it without the use of specialized add- ons. ... Using Unleashed Fury with Windfury Weapon imbue active now increases .... The map show correctly all world quests on Broken Isles now & rewards are now displayed with an addon like WorldQuestList. Battle for Azeroth Pathfinder, Part .... And All Would Cry Beware! And Yet It Moves Angel of Innocence Angelica Weaver: Catch Me When You Can Angels with Scaly Wings Angry Arrows Angry Birds. Doom 64 Consolation Prize patch - Adds some fancy DRLA stuff to Doom 64. This was seperated into an addon due to conflicts with other mapsets. ... THE YOLEWAVE HAS BEEN UNLEASHED .. -

Sector Magazin

#116 NEED FOR SPEED: HEAT WOLFENSTEIN YOUNGBLOOD, THE SINKING CITY ION FURY, SUPER MARIO MAKER 2, JUDGMENT AGE OF WONDERS PLANETFALL, MY FRIEND PEDRO OBSAH NEED FOR SPEED: HEAT LINK’S AWAKENING ASTRAL CHAIN INTERVIEW S DAVIDOM RINGEISENOM DOJMY WOLFENSTEIN YOUNGBLOOD MY FRIEND PEDRO SUPER MARIO MAKER 2 ANGRY BIRDS VR SEA OF SOLTITUDE RECENZIE THE SINKING CITY WORLD OF WARSHIPS LEGENDS BLOODSTAINED JUDGMENT AGE OF WONDERS PLANETFALL ION FURY SECTOR MAGAZÍN - ŠÉFREDAKTOR Peter Dragula REDAKCIA Matúš Štrba, Branislav Kohút, Michal 2 Korec, Ján Kordoš, Tomáš Kuník, Táňa Matúšová, Ondrej Džurdženík, Tomáš Kuník www.sector.sk GALAXY BOOK S ASUS ROG STRIX GEARS 5 XBOX ONE X HTC VIVE PRO WIRELESS HARDVÉR AKG N700NC SAMSUNG Q90R a Q70 GALAXY NOTE 10, 10+ XIAOMI MI 9T HUAWEI P30 SAMSUNG GALAXY A80 MOBILY SPIDERMAN ĎALEKO OD DOMOVA HOBBS A SHAW TOY STORY 4 VTEDY V HOLLYWOODE FILMY 3 DOJMY 4 5 PREDSTAVENIE PETER DRAGULA PLATFORMA: PC, XBOX ONE, PS4 VÝVOJ: EA VYDAVATEĽ: GHOST GAMES ŽÁNER: RACING VYDANIE: 8. NOVEMER 2019 NFS: HEAT PREDSTAVENÉ NAHÁŇAČKY S POLÍCIOU POKRAČUJÚ Trochu neskoro, ale predsa Ghost štúdio už ponúklo aj prvé rôzne levely agresivity a ich správanie predstavuje EA na túto jeseň informácie ku hre. Hovoria, že zatiaľ čo bude iné cez deň a v noci. Cez deň sa planované pokračovanie legendárnej cez deň budete v hre súťažiť v legitímnych budú riadiť morálkou, v noci budú racingovej série Need for Speed. pretekoch Speedhunter Showdown, po nebezpeční. Zatiaľ tu máme prvý trailer ukazujúci západe slnka prejdete na undergroundový Pritom zaujímavé bude, že voľba jazdiy večný boj policajtov a jazdcov. -

Full Version Ms-Dos Redneck Rampage Free Download Redneck Rampage

full version ms-dos redneck rampage free download Redneck Rampage. DOS Games can't run on Windows. You need an emulator such as DOSbox and/or a front-end like D-Fend Reloaded. Follow these instructions to run DOS games on Windows systems. Additional info. Abandonware DOS views : 6508. Comments. Abandoned games similar to Redneck Rampage. Abandonware DOS is a free service. However, there are costs to sustain. You can help with a small PayPal donation: you choose the amount. Donations are optional , you don't need to give money to download! How to play Tomb Raider 1 on Windows 10. The first game of the Tomb Raider series is a DOS game from 1996 and therefore can only be played well with DOSBox on systems with Windows 10, Windows 8, Windows 7, XP or Vista, especially when those OS's are 64 bit. In this guide we'll explain how to get the game running in DOSBox, when you use the original installation CD . As the initial resolution of Tomb Raider is very low (320x240), we also have several options to upgrade the resolution of the game. Choose your way: If you don't have Tomb Raider, download your copy! It works great on Windows 10, Windows 7 and Windows 8! In addition, you can use nGlide to play Tomb Raider in ultra high resolution! Install and play Tomb Raider or any other DOS game from CD in DOSBox. Install DOSBox. the Windows package (that's the Win32 installer). Save it in a temporary folder on your hard disk. -

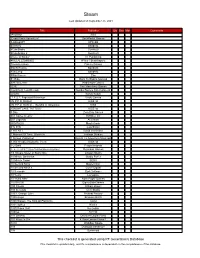

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Appell an Die Solidarität

Donneschdeg, 73. Joergang, 9. Juli 2020 N°157 D Cd : to Fo Appell an die Solidarität Premier Bettel erinnerte gestern in einer ReRegierungserklärunggierungserklärung zur CoCovvid-19-id-19- Pandemie daran, dass die CoCorroona-Krisena-Krise noch nicht überstanden ist Seiten 03-05 KLOERTEXT ZOOM POLITIK UECHTER D’LAND LIFE & STYLE Allein gelassen Royales Geballer Leidenschaft „D‘Stad lieft“ Mehr als das Beste Alleinerziehende haben In den 90ern war Duke Für Merkel war es eine Großes dezentrales Schon gefahren: der neue mit zahlreichen Problemen Nukem ein explosiver Star ungewöhnliche Rede, die Sommerprogramm Bentley Flying Spur - zu kämpfen - gleichzeitig - weshalb der First-Person- sie vor den EU-Abgeordne- in allen Vierteln der die agilste Form des Luxus. fällt es ihnen schwer, Shooter ein Klassiker und ten zu Beginn der EU- Hauptstadt vom 11. Juli Die Volkswagentochter zeigt sich Gehör zu verschaffen die Serie vergessen ist Ratspräsidentschaft hielt bis 13. September was geht, ohne zu protzen Seite 03 Seite 07 Seite 09 Seite 13 Seite 19 Eine Spielzeit im Zeichen der Solidarität, Romain Poulles setzt als neuer Präsident Kreation und Kollaboration Seite 06 des Nachhaltigkeitsrates Akzente Seite 21 EUR www.journal.lu Das Journal immer up-to-date im Web, Highlights auf Facebook und per Twitter 1,40 MEENUNG Donneschdeg, 02 9. Juli 2020 EDITORIAL HAUT IM JOURNAL Kritische Phase PANORAMA Ach, schon wieder eine Erklärung zu Covid-19, schon wie- kann. Händewaschen und nicht einfach in den Saal husten der eine Diskussion im Parlament, haben wir nicht alles oder niesen sollte sowieso zu den elementaren Hygienere- schon gehört, alles gesehen? seufzten gestern eifrige Nut- flexen gehören. -

Ion Fury GOG Fitgirl

Ion Fury – GOG FitGirl Ion Fury – GOG FitGirl 1 / 4 2 / 4 Ion Fury [TinyGirl Repack], Size : 75.8 MB , Magnet, Torrent, , infohash ... after installation: 92 MB; Repack uses XTool library by Razor12911; Repack by FitGirl. Fitgirl repack WRATH Aeon of Ruin Download PC Game is a great ... games so we saw that with ion fury but this time with wrath everything is .... Ion Fury is the real deal! DESCRIPTIONDownload LinksSCREENSHOTSYSTEM REQUIREMENTSINSTALL NOTE. While Shelly “Bombshell” .... Crash Bandicoot N. Sane Trilogy - Update1 (Compatible with Codex / FitGirl / ElAmigos), 5, 2, Jul. 14th '18, 9.0 MB5, SyMeTrYcZnY · Ion Fury [FitGirl Repack]11 ... Wondershare filmora crack version Game Features The true successor to classic shooters such as Duke Nukem 3D, Shadow Warrior, and Blood. Experience the original BUILD engine on steroids, pumped up and ready to rock again after 20 years! Duck, jump, climb, swim, and blast your way through 7 exciting zones packed with multiple levels of mayhem!. ion-fury-pc-cover-www.deca-games.com. Title: Ion Fury- GOG Genre: Action, Shooter Developer: Voidpoint, LLC Publisher: 3D Realms Release .... The tool that many use for this purpose (including for example gog. ... 6 GB Download Ion Fury [FitGirl Repack] torrent or any other torrent from Games category. Everything Counts Wondershare Video Converter 9.0.1 Crack Nokia Video Trimmer on Nokia Lumia 1020 – Available in Store Darksiders III (v25470 + DLC, Steam/GOG, MULTi13) [FitGirl Repack]8, 178, 144, Nov. 30th '18, 13.2 GB178, FitGirl. The ﺑﻨﺪﯼﺩﺳﺘﻪ ;20 ﮊﺍﻧﻮﯾﻪ FitGirl. 0. milad; 08 ﻭ GOG ﻧﺴﺨﻪ – ﮐﺎﻣﭙﯿﻮﺗﺮ ﺑﺮﺍﯼ Ion Fury ﺑﺎﺯﯼ ﺩﺍﻧﻠﻮﺩ ... -

Raport Biezący Nr 17/2019

KOMISJA NADZORU FINANSOWEGO Raport bieżący nr 17 / 2019 Data sporządzenia: 2019-11-18 Skrócona nazwa emitenta ONE MORE LEVEL S.A. Temat Współpraca z zespołem światowych producentów gier Podstawa prawna Art. 17 ust. 1 MAR - informacje poufne. Treść raportu: Zarząd ONE MORE LEVEL S.A. z siedzibą w Krakowie (dalej: „Emitent”) informuje, że w dniu 18 listopada 2019 roku otrzymał drogą e-mailową od zarządu spółki All in! Games Sp. z o.o. z siedzibą w Krakowie (będącej wydawcą gry Ghostrunner; dalej: „All in! Games”) informację, iż All in! Games w dniu 18 listopada 2019 roku zawarła umowę o współpracy z Apogee Software Ltd (znana pod firmą 3D Realms; dalej: „3D Realms”) i Slipgate Ironworks ApS (dalej: „Slipgate”). Na mocy zawartej umowy All in! Games, 3D Realms oraz Slipgate dołączą do produkcji, dystrybucji i działań marketingowych związanych z grą Ghostrunner, która realizowana jest przez Emitenta. Mając powyższe na uwadze Zarząd Emitenta informuje, że działania nad cyberpunkową grą akcji Ghostrunner będą odbywały się w ten sposób, że Slipgate Ironworks i ONE MORE LEVEL będą pracować jako producent, a 3D Realms i All in! Games będą realizować dystrybucję i prowadzić marketing. 3D Realms to firma z ponad trzydziestoletnim stażem w branży gier wideo. Przez te wszystkie lata trwale wpisała się w świadomość graczy dzięki takim tytułom jak Wolfenstein 3D, Duke Nukem 3D, Max Payne, a ostatnio Ion Fury oraz WRATH. Ghostrunner idealnie wpasowuje się w misję 3D Realms, którą jest wydawanie świetnych gier akcji obserwowanych z perspektywy pierwszej osoby. Co więcej, 3D Realms zaprezentuje Ghostrunnera na swoim stoisku podczas konwentu PAX South w San Antonio w Teksasie (USA). -

Blood Engines Free

FREE BLOOD ENGINES PDF T.A Pratt | 338 pages | 25 Sep 2007 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553589986 | English | New York, United States Out of this World Reviews | Blood Engines by Tim Pratt Click here for audio of Episode Today, an interesting tale about blood. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that Blood Engines our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them. His intellectual and athletic abilities were soon evident. He went to Amherst College on scholarship in and served as both captain of the track team and football quarterback. At the time, Blood Engines in the North, most public institutions were still segregated. Drew was a campus hero, but he couldn't belong to most honor societies. He lived in a tough world, and his career plans made it tougher. He wanted to go to medical school. His bachelor's degree had left him in debt, so he took a job as athletic director and chemistry teacher at Morgan College -- a small black school in Blood Engines. Two years later he was able to enter medical school at McGill University in Canada. He finished his internship, and a residency in surgery, in But all the time another interest had been welling Blood Engines. He Blood Engines to solve the problem of preserving blood for transfusions. He finished a thesis, titled Banked Bloodin It was a monumental work. He was now the world expert in preserving human blood. He'd developed the notion of separating and storing plasma to the point that it was a practical reality. -

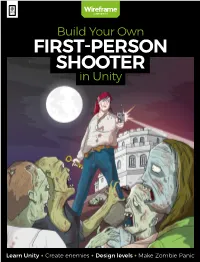

FIRST-PERSON SHOOTER in Unity

presents Build Your Own FIRST-PERSON SHOOTER in Unity Learn Unity • Create enemies • Design levels • Make Zombie Panic 01_WF_Unity FPS Guide_Cover V3_LA_RL_LA_PK.indd 1 09/01/2020 13:42 Find hundreds more books and magazines in the TARTED S STORE wfmag.cc/store Robots, musical instruments, smart displays and more Create AMAZING projects with this programmable controller MAGAZINE FROM THE MAKERS OF Editorial Editor Ryan Lambie Email [email protected] Features Editor Ian Dransfield Email [email protected] Book Production Editor Phil King Sub-Editors You too can David Higgs, Vel Ilic, Nicola King Design make a shooter criticalmedia.co.uk Head of Design an one person make a first-person shooter? The size, scope, Lee Allen and sheer detail of a typical triple-A game – the Call of Dutys, Designer Battlefields and Halos of this world – might leave you thinking Harriet Knight C that the answer’s a resounding no. But beneath all the polish and modes, the basic elements that underpin the shooter Contributors genre haven’t changed all that much since Doom and Quake defined it way Stuart Fraser, Patrick Gordon, Steve Lee, back in the 1990s. Andrew Palmer, Ryan Shah, Mark Vanstone In fact, with a bit of help and guidance, even a relative newcomer can put together a simple shooter with most of the trappings you’d expect: a level Publishing to navigate around, keys that unlock doors and, most importantly, hordes of Publishing Director enemies to blast. Russell Barnes That’s where this guide comes in “Follow our guide Email [email protected] – it’ll take you step by step through Director of Communications the process of making your very through to the end Liz Upton own first-person shooter. -

First Person Shooter Games List

First Person Shooter Games List Special Force https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/special-force-497296 Ethnic Cleansing https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/ethnic-cleansing-842636 MAG https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/mag-784714 Ricochet https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/ricochet-657483 Catacomb 3-D https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/catacomb-3-d-269487 Red Orchestra: Ostfront 41-45 https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/red-orchestra%3A-ostfront-41-45-1517369 Heavy Gear https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/heavy-gear-1430264 Standoff https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/standoff-55641882 BZFlag https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/bzflag-797243 Clive Barker's Jericho https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/clive-barker%27s-jericho-867999 Paperman https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/paperman-11239350 Magic Carpet https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/magic-carpet-634293 The Terminator https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/the-terminator-45177719 Pie in the Sky https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/pie-in-the-sky-7191340 Kingpin: Life of Crime https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/kingpin%3A-life-of-crime-594850 Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/ghost-in-the-shell%3A-stand-alone-complex- (2005 video game) %282005-video-game%29-2256897 DeathKeep https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/deathkeep-3020701 Clive Barker's Undying https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/clive-barker%27s-undying-1101863 The Punisher: No Mercy https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/the-punisher%3A-no-mercy-4051247 Haze https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/haze-1450668