Benjamin, the Man: His Place in Nephite History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Hypothesis Concerning the Three Days of Darkness Among the Nephites

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 2 Number 1 Article 8 1-31-1993 An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites Russell H. Ball Atomic Energy Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ball, Russell H. (1993) "An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol2/iss1/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title An Hypothesis concerning the Three Days of Darkness among the Nephites Author(s) Russell H. Ball Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2/1 (1993): 107–23. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Aspects of the three days of darkness following the three-hour period of intense destruction described principally in 3 Nephi include: (1) the strange absence of rain among the destructive mechanisms described; (2) the source of the intense lightning, which seems to be unaccompanied by rain; (3) a mechanism to account for the inundation of the cities of Onihah, Mocum, and Jerusalem, which were not among the cities which “sunk in the depths of the sea”; and (4) the absence in the histories of contemporary European and Asiatic civilizations of corresponding events, which are repeat- edly characterized in 3 Nephi as affecting “the face of the whole earth.” An -Hypothesis concerning the Three Days ·of Darkness among the Nephites Russell H. -

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

The Name Mormon in Reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages

The Name Mormon in reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages by Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG May 1, 2017 Blind third party peer review performed by After obtaining the golden plates, Joseph Smith stated that once he moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in the winter of 1827, he “commenced copying the characters of[f] the plates.” He stated: I copyed a considerable number of them and by means of the Urim and Thummin I translated some of them.1 In the mid 1830s, Oliver Cowdery and Frederick G. Williams recorded four characters that had been copied from the plates and Joseph Smith’s translations of those characters; one set of two characters was translated together as “The Book of Mormon” and the other set of two characters was translated as “The interpreters of languages” (see figures 1 and 2). Both of these phrases can be found in the original script of the current Title Page of the Book of Mormon. It clearly includes “Book of Mormon,” mentions “interpretation,” and infers the language of the Book of Mormon. It is reasonable therefore to assume that these characters came from the Title Page. Figure 1. Book of Mormon characters copied by Oliver Cowdery, circa 1835–1836 1 Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers: Histories, Volume 1 (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 1:240. 1 Figure 2. Close-up of the Book of Mormon characters copied by Fredrick G. Williams, circa February 27, 1836 (MacKay et al. 2013, 137) 2 In a 2015 publication, I successfully translated all four of these characters from known hieratic and Demotic Egyptian glyphs.3 The name Mormon (second glyph of the first set of two) in the “reformed Egyptian” is an interesting case study. -

Mosiah the Lack of a Preface for the Book of Mosiah in the Present Book

Book of Mormon Commentary Mosiah 1 Mosiah The lack of a preface for the book of Mosiah in the present Book of Mormon is probably because the text takes 1 up the Mosiah account some time after its original beginning. The original manuscript of the Book of Mormon, written in Oliver Cowdery’s hand, has no title for the Book of Mosiah. It was inked in later, prior to sending it to the printer for typesetting. The first part of Mormon’s abridgment of Mosiah’s record…was evidently on the 116 pages lost by Martin Harris. John A. Tvedtnes, Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. By John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne [Salt Lake City: 1991], 33 Note that the main story in the book of Mosiah is told in the third person rather than in the first person as was the 2 custom in the earlier books of the Book of Mormon. The reason for this is that someone else is now telling the story and that “someone else” is Mormon. With the beginning of the book of Mosiah we start our study of Mormon’s abridgment of various books that had been written on the large plates of Nephi (3 Nephi 5:8-12). The book of Mosiah and the five books that follow—Alma, Helaman, 3 Nephi, 4 Nephi, and Mormon—were all abridged or condensed by Mormon from the large plates of Nephi, and these abridged versions were written by Mormon on the plates that bear his name, the plates of Mormon. These are the same plates that were given to Joseph Smith by the angel Moroni on September 22, 1827. -

“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton's Dissent

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2020-8 “They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent Dan Belnap Brigham Young University, [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Dan and Belnap, Daniel L., "“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent" (2020). Faculty Publications. 4479. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4479 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ILLUMINATING THE RECORDS Edited by Daniel L. Belnap Published by the Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, in cooper- ation with Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City. Visit us at rsc.byu.edu. © 2020 by Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. DESERET BOOK is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company. Visit us at DeseretBook.com. Any uses of this material beyond those allowed by the exemptions in US copyright law, such as section 107, “Fair Use,” and section 108, “Library Copying,” require the written permission of the publisher, Religious Studies Center, 185 HGB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of Brigham Young University or the Religious Studies Center. -

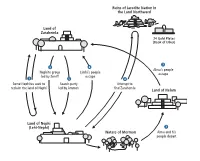

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 51 | Issue 4 Article 10 12-1-2012 When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M. Lyon Kent R. Minson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Lyon, Jack M. and Minson, Kent R. (2012) "When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 51 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol51/iss4/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Lyon and Minson: When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Page from the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon, showing on line 3 the beginning of the book of Mosiah. Courtesy Community of Christ, Independence, Missouri. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2012 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 51, Iss. 4 [2012], Art. 10 When Pages Collide Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M. Lyon and Kent R. Minson erses 12–18 of the Words of Mormon have always been a bit of a puzzle. VFor stylistic and other reasons, they do not really fit with verses 1–11, so commentators have tried to explain their presence as a sort of “bridge” or “transition” that Mormon wrote to connect the record of the small plates with his abridgment from the large plates.1 This paper proposes a different explanation: Rather than being a bridge into the book of Mosiah, these verses were originally part of the book of Mosiah and should be included with it. -

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell Narrator: From the dawn of Creation, mankind looked forward to the central event of the Holy Scriptures—the coming of the promised Messiah—the KING OF KINGS. The dispensations of Adam and Enoch, Noah, Abraham and Moses all kept and treasured this most precious message. A Redeemer would come to save the world from sin and error. The children of the covenant, those descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, made their way to Egypt in the time of famine, to find their brother Joseph in a position of power. There they flourished, and then became enslaved. At last the 400-year sojourn in Egypt came to an end with the mighty Proclamation of Moses, “Let my people go.” The Red Sea parted for these children of the covenant and they gave thanks for their escape. Arriving in the Promised Land, they built a Temple to the Most High God. For a thousand years they kept alive the treasured Word. The Law of Moses was their constant reminder of the coming of the Redeemer. Voice of Sariah: The prophet Isaiah Spoke: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son and shall call his name Immanuel. For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. “(Isaiah 9:6) Choir: O Little Town of Bethlehem Narrator: The beautiful Temple of Solomon was destroyed by the invading Babylonians in 587 B.C. -

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles John A. Tvedtnes A portion of the brass plates brought by Lehi to the New World contained the books of Moses (1 Nephi 5:10-13). Nephi and other Book of Mormon writers stressed that they obeyed the laws given therein: “And we did observe to keep the judgments, and the statutes, and the commandments of the Lord in all things according to the law of Moses” (2 Nephi 5:10). But aside from sacrice2 and the Ten Commandments,3 we have few explicit details regarding the Nephite observance of the Mosaic code. One would expect, for example, some mention of the festivals which played such an important role in the religious observances of ancient Israel. Though the Book of Mormon mentions no religious festivals by name, it does detail many signicant Nephite assemblies. One of the more noteworthy of the Nephite ceremonies was the coronation of the second Mosiah by his father, Benjamin.4 Some years ago, Professor Hugh Nibley outlined the similarities between this Book of Mormon account and ancient Middle Eastern coronation rites.5 He pointed out that these rites took place at the annual New Year festival, when the people were placed under covenant of obedience to the monarch. My own research further explores the Israelite coronation/New Year rites, and aims to complement other scholarly studies of the ceremonial context of Benjamin’s speech. THE SABBATICAL FEASTS In the sacred calendar, the Israelite new year began with the month of Abib (later called Nisan), in the spring (end March/beginning April).6 This month encompassed the feasts of Passover (beginning at sundown on the fourteenth day) and Unleavened Bread (fourteenth through twenty-first days), and included “holy convocations,” analogous to the Latter-day Saint April general conference (Leviticus 23:4-8). -

What Does the Book of Mormon Teach About Prophets?

What Does the Book of Mormon Teach about Prophets? “He ... cried with a loud voice, and prophesied unto the people whatsoever things the Lord put into his heart.” Helaman 13:4 KnoWhy # 284 March 8, 2017 Four Prophets by Robert T. Barrett via lds.org Principle When Samuel the Lamanite prophesied on the walls of to foretell coming events, to utter prophecies, which is Zarahemla, he spoke the words that “the Lord put into only one of the several prophetic functions.”1 A careful his heart” (Helaman 13:4). When the prophet Alma the look at the Book of Mormon shows, as Elder Widtsoe Younger met his soon-to-be companion, Amulek, he noted, that prophets do a lot more than tell the future. told him that he had “been called to preach the word of God among all this people, according to the spirit of Although about half of the references to prophets and revelation and prophecy” (Alma 8:24). Jacob, the son of prophecy in the Book of Mormon involve cases in which Lehi, said that he had “many revelations and the spirit the prophet was involved in telling about things to come, of prophecy” (Jacob 4:6). The Nephites often appointed they are often shown doing many other things as well.2 as their chief captains “some one that had the spirit of The prophet Alma, for example, was able to know the revelation and also prophecy” (3 Nephi 3:19). All told, thoughts of Zeezrom “according to the spirit of prophe- the Book of Mormon mentions prophets or prophecy cy” (Alma 12:7), an act of discerning the present rather over 350 times. -

Archaeology and the Book of Mormon

Archaeology and the Book of Mormon Since the publication of the Book of Mormon in 1830, during the approximate period the events related in the both Latter-day Saint (LDS or Mormons) and non- Book of Mormon are said to have occurred. Mormon archaeologists have studied its claims in ref- Some contemporary LDS scholars suggest that the Jared- erence to known archaeological evidence. Members of ites may have been the Olmec, and that part of the Maya The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS may have been the Nephites and Lamanites.[17] Church) and other denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement generally believe that the Book of Mormon 19th century archaeological finds (e.g. earth and tim- describes ancient historical events in the Americas, but ber fortifications and towns,[18] the use of a plaster- mainstream historians and archaeologists do not regard like cement,[19] ancient roads,[20] metal points and the Book of Mormon as a work of ancient American his- implements,[21] copper breastplates,[22] head-plates,[23] tory. textiles,[24] pearls,[25] native North American inscrip- tions, North American elephant remains etc.) are not The Book of Mormon describes God’s dealings with three [1] interpreted by mainstream academia as proving the his- heavily populated, literate, and advanced civilizations toricity or divinity of the Book of Mormon.[26] The Book in the Americas over the course of several hundred years. of Mormon is viewed by many mainstream scholars as a The book primarily deals with the Nephites and the work of fiction that parallels others within the 19th cen- Lamanites, who it states existed in the Americas from tury “Mound-builder” genre that were pervasive at the about 600 BC to about AD 400.