An Educational-Linguistic Study of Scripted Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behind the Scenes: Monk's Final Case

lot, the gushing well-wishers and co- workers moving towards him, the gauntlet of handshakes and bear hugs, people drinking champagne November 23, 2009 straight out of bottles, eating red velvet cake with their bare hands, crying, embracing; a seething mass Behind The of humanity, slowly closing in. But Tony Shalhoub isn’t Scenes: Adrian Monk. Not any more. After eight years of Monk’s obsessive-compulsive hand-wiping, pole-touching and mystery-solving “Monk.” the often under-appreciated Final Case show that re-vitalized USA Network, made Shalhoub into an Emmy- By Joe Rhodes winning star and spawned a wave of quirkily-observant tv detective imitators, has finally come to an end. The final episode, because this is “Monk,” will put everything in its place. Before it ends – with a Randy Newman song written especially for the finale – loyal viewers will have the answers they’ve been waiting for: Who killed Monk’s wife, Trudy, the crime that sent him into a catatonic state and has hung over the series from the very first episode? Will he be reinstated as a San Francisco detective? Will he ever unbutton that top shirt button? Is that Captain Mr. Monk would not have enjoyed Stottlemeyer’s real hair? (Ok, not the this; the way things ended after the last one). 25th and final take of the final shot of the final season of the show that There will, of course, be bears his name. Adrian Monk, complications along the way, not the germophobic, claustrophobic, least of which is that Monk will be emotion-phobic, would have been told he has only three days to live. -

Jon's Mini-Codiums and More 2016

Jon's Mini-codiums and More 2016 I want to thank all of the people that ordered bulbs from me last year. This was my first time getting orders filled and it was a learning experience. After many years of drought conditions in California, it finally rained. Here in the San Francisco Bay Area, we had ample amounts of rain. My daffodils were very happy. My earliest daffodils (fall flowering species such as N. virdiflorus, N. miniatus, and N. serotinus, and fall flowering bulbocodiums bloomed.) started blooming in October 2015. More fall bloomers flowered (fall blooming cultivars, tazettas, bulbocodiums which included N. cantabricus, N. romieuxii, and Division 10 cultivars) in November and December. Many of the late winter / early spring bloomers (particularly the miniatures in Division 1, 2, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12) grew vigorously and bloomed during the months of January through early March. The season was going to be early again. During the end of February and first week of March, I was in Arizona on vacation (went to baseball spring training), and upon our return home, it stormed and noticed that most of the miniatures that were coming Spring Serenade into bloom were ravaged by the heavy winds, rain, 5 Y-Y and pests. A few days before the Northern California Daffodil Chapter’s Murphys Show (on March 19 and 20), I was able to bring a small number of miniatures to the show. The next week, I was able to bring many of my late flowering miniatures to the Fortuna Show. Nancy and Jerry Wilson attended the show. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Mr Monk on Patrol Kindle

MR MONK ON PATROL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lee Goldberg | 278 pages | 05 Jul 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451236647 | English | New York, United States Mr. Monk Is a Mess - Wikipedia I'm a sucker for these books. Look down your nose if you must, but I like the character of Adrian Monk and I enjoy veteran TV mystery writer, Lee Goldberg's take on the continuing and ever evolving, Monkverse. Apparently this is the penultimate Mr. Monk book. Goldberg uses Monk's long-suffering assistant, Natalie as the narrator of his books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the g I'm a sucker for these books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the growth of the characters forward. This is probably the part I most enjoy. The book begins with a fun mystery an excerpt of which was published as a short in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and shortlisted for an Edgar Award. Things aren't going well. Well, they are, sort of. Apparently hired in part because of a reputation as a competent, but ridiculous cop, the folks who hired him didn't count on how personable, earnest and hard-working Disher is or his uncanny ability to literally stumble into mysteries. Disher found and reported rampant, years-long corruption in the Summit city government. This lead to the resignation of the mayor and most of the town council. -

Language Development Language Development

Language Development rom their very first cries, human beings communicate with the world around them. Infants communicate through sounds (crying and cooing) and through body lan- guage (pointing and other gestures). However, sometime between 8 and 18 months Fof age, a major developmental milestone occurs when infants begin to use words to speak. Words are symbolic representations; that is, when a child says “table,” we understand that the word represents the object. Language can be defined as a system of symbols that is used to communicate. Although language is used to communicate with others, we may also talk to ourselves and use words in our thinking. The words we use can influence the way we think about and understand our experiences. After defining some basic aspects of language that we use throughout the chapter, we describe some of the theories that are used to explain the amazing process by which we Language9 A system of understand and produce language. We then look at the brain’s role in processing and pro- symbols that is used to ducing language. After a description of the stages of language development—from a baby’s communicate with others or first cries through the slang used by teenagers—we look at the topic of bilingualism. We in our thinking. examine how learning to speak more than one language affects a child’s language develop- ment and how our educational system is trying to accommodate the increasing number of bilingual children in the classroom. Finally, we end the chapter with information about disorders that can interfere with children’s language development. -

Theories of Language Acquisitionq Susan Goldin-Meadow, University of Chicago, Departments of Psychology and Comparative Human Development, Chicago, IL, USA

Theories of Language Acquisitionq Susan Goldin-Meadow, University of Chicago, Departments of Psychology and Comparative Human Development, Chicago, IL, USA © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Theoretical Accounts of Language-Learning 1 Behaviorist Accounts 1 Nativist Accounts 2 Social/Cognitive Accounts 3 Connectionist Accounts 3 Constrained Learning 4 Constrained Invention 5 Is Language Innate? 7 Innateness Defined as Genetic Encoding 7 Innateness Defined as Developmental Resilience 7 Language Is Not a Unitary Phenomenon 8 References 8 The simplest technique to study the process of language-learning is to do nothing more than watch and listen as children talk. In the earliest studies, researcher parents made diaries of their own child’s utterances (e.g., Stern and Stern, 1907; Leopold, 1939–1949). The diarist’s goal was to write down all of the new utterances that the child produced. Diary studies were later replaced by audio and video samples of talk from a number of children, usually over a period of years. The most famous of these modern studies is Roger Brown’s (1973) longitudinal recordings of Adam, Eve, and Sarah. Because transcribing and analyzing child talk is so labor-intensive, each individual language acquisition study typically focuses on a small number of children, often interacting with their primary caregiver at home. However, advances in computer technology have made it possible for researchers to share their transcripts of child talk via the computerized Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES, https://childes.talkbank.org). Because this system makes available many transcripts collected by different researchers, a single researcher can now call upon data collected from spontaneous interactions in naturally occurring situations across a wide range of languages, and thus test the robustness of descriptions based on a small sample. -

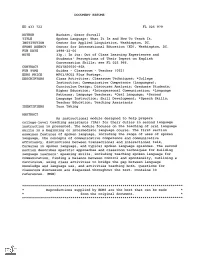

What It Is and How to Teach It. Center for Applied Linguistics, W

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 722 FL 025 979 AUTHOR Burkart, Grace Stovall TITLE Spoken Language: What It Is and How To Teach It. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-12-00 NOTE 33p.; In its: Out of Class Learning Experiences and Students' Perceptions of Their Impact on English Conversation Skills; see FL 025 966. CONTRACT PO17A50050 -95A PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; Classroom Techniques; *College Instruction; Communicative Competence (Languages); Curriculum Design; Discourse Analysis; Graduate Students; Higher Education; *Interpersonal Communication; *Language Patterns; Language Teachers; *Oral Language; *Second Language Instruction; Skill Development; *Speech Skills; Teacher Education; Teaching Assistants IDENTIFIERS Turn Taking ABSTRACT An instructional module designed to help prepare college-level teaching assistants (TAs) for their duties in second language instruction is presented. The module focuses on the teaching of oral language skills in a beginning or intermediate language course. The first section examines features of spoken language, including the range of uses of spoken language, the concepts of communicative competence and communicative efficiency, distinctions between transactional and interactional talk, formulas in spoken language, and typical spoken language episodes. The second section describes specific approaches and classroom techniques for building language learners' speaking skills, including teaching spoken language for communication, finding a balance between control and spontaneity, outlining a curriculum, using class activities to bridge the gap between language knowledge and language use, and activities teaching both. Questions for classroom discussion are dispersed throughout the text. Contains 30 references. -

Characteristics of Spoken and Written Communication in the Opening and Closing Sections of Instant Messaging

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 1-23-2014 Characteristics of Spoken and Written Communication in the Opening and Closing Sections of Instant Messaging Kenta Nishimaki Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nishimaki, Kenta, "Characteristics of Spoken and Written Communication in the Opening and Closing Sections of Instant Messaging" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1547 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Characteristics of Spoken and Written Communication in the Opening and Closing Sections of Instant Messaging by Kenta Nishimaki A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Japanese Thesis Committee: Suwako Watanabe, Chair Patricia J. Wetzel Emiko Konomi Portland State University 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines opening and closing segments in instant messaging (IM) and demonstrates how openings and closings differ between oral conversation and instant messaging as well as the factors that account for the difference. Many researchers have discussed the differences and similarities between spoken and written languages. Tannen (1980) claims that spoken and written languages are not distinct categories and there is a continuum between them. -

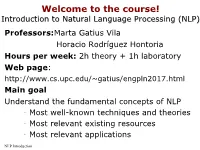

Lexical Ambiguity • Syntactic Ambiguity • Semantic Ambiguity • Pragmatic Ambiguity

Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing (NLP)(NLP) Professors:Marta Gatius Vila Horacio Rodríguez Hontoria Hours per week: 2h theory + 1h laboratory Web page: http://www.cs.upc.edu/~gatius/engpln2017.html Main goal Understand the fundamental concepts of NLP • Most well-known techniques and theories • Most relevant existing resources • Most relevant applications NLP Introduction 1 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Content 1. Introduction to Language Processing 2. Applications. 3. Language models. 4. Morphology and lexicons. 5. Syntactic processing. 6. Semantic and pragmatic processing. 7. Generation NLP Introduction 2 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Assesment • Exams Mid-term exam- November End-of-term exam – Final exams period- all the course contents • Development of 2 Programs – Groups of two or three students Course grade = maximum ( midterm exam*0.15 + final exam*0.45, final exam * 0.6) + assigments *0.4 NLP Introduction 3 Welcome to the course! IntroductionIntroduction toto NaturalNatural LanguageLanguage ProcessingProcessing Related (or the same) disciplines: •Computational Linguistics, CL •Natural Language Processing, NLP •Linguistic Engineering, LE •Human Language Technology, HLT NLP Introduction 4 Linguistic Engineering (LE) • LE consists of the application of linguistic knowledge to the development of computer systems able to recognize, understand, interpretate and generate human language in all its forms. • LE includes: • Formal models (representations of knowledge of language at the different levels) • Theories and algorithms • Techniques and tools • Resources (Lingware) • Applications NLP Introduction 5 Linguistic knowledge levels – Phonetics and phonology. Language models – Morphology: Meaningful components of words. Lexicon doors is plural – Syntax: Structural relationships between words. -

Conference Abstracts

EIGHTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Held under the Patronage of Ms Neelie Kroes, Vice-President of the European Commission, Digital Agenda Commissioner MAY 23-24-25, 2012 ISTANBUL LÜTFI KIRDAR CONVENTION & EXHIBITION CENTRE ISTANBUL, TURKEY CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS Editors: Nicoletta Calzolari (Conference Chair), Khalid Choukri, Thierry Declerck, Mehmet Uğur Doğan, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Asuncion Moreno, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis. Assistant Editors: Hélène Mazo, Sara Goggi, Olivier Hamon © ELRA – European Language Resources Association. All rights reserved. LREC 2012, EIGHTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Title: LREC 2012 Conference Abstracts Distributed by: ELRA – European Language Resources Association 55-57, rue Brillat Savarin 75013 Paris France Tel.: +33 1 43 13 33 33 Fax: +33 1 43 13 33 30 www.elra.info and www.elda.org Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Copyright by the European Language Resources Association ISBN 978-2-9517408-7-7 EAN 9782951740877 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the European Language Resources Association ii Introduction of the Conference Chair Nicoletta Calzolari I wish first to express to Ms Neelie Kroes, Vice-President of the European Commission, Digital agenda Commissioner, the gratitude of the Program Committee and of all LREC participants for her Distinguished Patronage of LREC 2012. Even if every time I feel we have reached the top, this 8th LREC is continuing the tradition of breaking previous records: this edition we received 1013 submissions and have accepted 697 papers, after reviewing by the impressive number of 715 colleagues. -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward. -

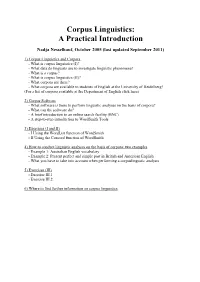

Corpus Linguistics: a Practical Introduction

Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Introduction Nadja Nesselhauf, October 2005 (last updated September 2011) 1) Corpus Linguistics and Corpora - What is corpus linguistics (I)? - What data do linguists use to investigate linguistic phenomena? - What is a corpus? - What is corpus linguistics (II)? - What corpora are there? - What corpora are available to students of English at the University of Heidelberg? (For a list of corpora available at the Department of English click here) 2) Corpus Software - What software is there to perform linguistic analyses on the basis of corpora? - What can the software do? - A brief introduction to an online search facility (BNC) - A step-to-step introduction to WordSmith Tools 3) Exercises (I and II) - I Using the WordList function of WordSmith - II Using the Concord function of WordSmith 4) How to conduct linguistic analyses on the basis of corpora: two examples - Example 1: Australian English vocabulary - Example 2: Present perfect and simple past in British and American English - What you have to take into account when performing a corpuslingustic analysis 5) Exercises (III) - Exercise III.1 - Exercise III.2 6) Where to find further information on corpus linguistics 1) Corpus Linguistics and Corpora What is corpus linguistics (I)? Corpus linguistics is a method of carrying out linguistic analyses. As it can be used for the investigation of many kinds of linguistic questions and as it has been shown to have the potential to yield highly interesting, fundamental, and often surprising new insights about language, it has become one of the most wide-spread methods of linguistic investigation in recent years. -

A New Venture in Corpus-Based Lexicography: Towards a Dictionary of Academic English

A New Venture in Corpus-Based Lexicography: Towards a Dictionary of Academic English Iztok Kosem1 and Ramesh Krishnamurthy1 1. Introduction This paper asserts the increasing importance of academic English in an increasingly Anglophone world, and looks at the differences between academic English and general English, especially in terms of vocabulary. The creation of wordlists has played an important role in trying to establish the academic English lexicon, but these wordlists are not based on appropriate data, or are implemented inappropriately. There is as yet no adequate dictionary of academic English, and this paper reports on new efforts at Aston University to create a suitable corpus on which such a dictionary could be based. 2. Academic English The increasing percentage of academic texts published in English (Swales, 1990; Graddol, 1997; Cargill and O’Connor, 2006) and the increasing numbers of students (both native and non-native speakers of English) at universities where English is the language of instruction (Graddol, 2006) testify to the important role of academic English. At the same time, research has shown that there is a significant difference between academic English and general English. The research has focussed mainly on vocabulary: the lexical differences between academic English and general English have been thoroughly discussed by scholars (Coxhead and Nation, 2001; Nation, 2001, 1990; Coxhead, 2000; Schmitt, 2000, Nation and Waring, 1997; Xue and Nation, 1984), and Coxhead and Nation (2001: 254–56) list the following four distinguishing features of academic vocabulary: “1. Academic vocabulary is common to a wide range of academic texts, and generally not so common in non-academic texts.