Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolgan Valley DISCOVERY TRAIL

Wolgan Valley DISCOVERY TRAIL Following this Discovery Trail Drive summary leads to a spectacular return • 35km (one way), • 1hr to drive (one way) drive down the mighty, cliff- • Highway, narrow sealed roads, unsealed roads (dry weather only) • Start: Lidsdale (on The Greater Blue Mountains Drive) bound Wolgan Valley to the • Finish: Newnes historic Newnes industrial • Alerts!: Narrow, winding roads unsuitable for carvans. Wolgan Valley road is also unsuitable in wet conditions. area in Wollemi National Park. � ������ � Highlights along the way � ��������� � include Blackfellows Hand Rock � ������ � � ��������� � ������ and Wolgan Valley scenery. � ����� ������ �� Route Description ������ ��� ������ From Lidsdale, a small village north of ������ ������������� ���� Lithgow on the Castlereagh Highway (also ���� The Tablelands Way and The Greater Blue � �� ������ ������ � Mountains Drive), take the sealed Wolgan � �� � � �������� � � � � � Road on the right. � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �� � � It travels through the valley of the upper � � � � � � � � Coxs River to Wolgan Gap and a very steep � � � � � � � � � � and winding descent into the Wolgan � � � � � Valley. Just before the gap, a small unsealed �� � � ������������� �� � � � � � � road on the right leads one kilometre to �� � � � � � � � � a short walk to Blackfellows Hand Rock, � � � � � � � � � � � � where Aboriginal stencil art can be viewed. ���������� � � � � � � �� Continue on the road through the Wolgan � � ������������ Valley which is mostly unsealed with some � � ��������� -

GBMWHA Summary of Natural & Cultural Heritage Information

GREATER BLUE MOUNTAINS WORLD HERITAGE AREA Summary of Natural & Cultural Heritage Information compiled by Ian Brown Elanus Word and Image for NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service November 2004 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. Essential Facts 3 3. World Heritage Values 5 4. Geography, Landscape and Climate 6 5. Geology and Geomorphology 8 6. Vegetation 13 7. Fauna 15 8. Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 16 9. Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 18 10. Conservation History 20 11. Selected References 24 Summary of Natural and Cultural Heritage Information Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area November 2004 1 1. INTRODUCTION This document was prepared as a product of the Interpretation and Visitor Orientation Plan for the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. It is intended primarily as a summary reference of key information for use by those who are preparing public information and interpretation for the world heritage area. It is not intended to be fully comprehensive and anyone requiring detailed information on any topic is encouraged to refer to the list of selected references and additional material not listed. It is also recommended that all facts quoted here are checked from primary sources. A major source for this document was the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Nomination (see reference list), which is a very useful compendium of information but of limited availability. All other key sources used in compiling this summary are listed in the references, along with some other useful documents which were not consulted. Some items of information contained here (eg. total area of wilderness and comparisons with other east coast wilderness areas) have been derived from original research for this project. -

Lloa Info Emiratesoneonlywol

ACTIVITIES ACTIVITIES With an inspiring combination of imposing escarpments, luscious green valleys and curious native wildlife, the 7,000-acre wildlife reserve at Emirates One&Only Wolgan Valley is waiting to be explored. ACTIVITIES With an inspiring combination of imposing escarpments, luscious green valleys and curious native wildlife, the 7,000-acre wildlife reserve at Emirates One&Only Wolgan Valley is waiting to be explored. Home to a unique range of native wildlife and flora, with an ancient geological heritage, guests can enjoy a range of guided tours and exciting activities. Discover the countryside on horseback, tour by 4WD vehicle, mountain bike through the valley or simply gaze at a canopy of stars in the stillness of the night. With so many unique experiences to choose from, the resort’s knowledgeable and experienced Field Guides are happy to recommend activities and experiences to inspire a love for Australia’s great outdoors. There are three tiers of activities available: INCLUSIVE ACTIVITIES Group experiences shared with other guests and included in all accommodation packages (up to two activities per day). SIGNATURE EXPERIENCES Social experiences shared with other guests and scheduled at regular times throughout the week. These tours are available for an additional fee. The range of tours included in this category may vary throughout the year, depending on seasonal highlights. PRIVATE TOURS Exclusive experiences tailored to your preference, hosted by your personal Field Guide and scheduled on request. Please note, weather in Wolgan Valley and the Blue Mountains region can vary. All activities are subject to suitable weather conditions. Comfortable outdoor clothing, appropriate to the season, is recommended for all outdoor activities. -

TRANSFERS 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021

TRANSFERS 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021 Emirates One&Only Wolgan Valley is located approximately 190 kilometres or a three-hour drive from Sydney in the World Heritage-listed Greater Blue Mountains region. Guests can arrive to the resort in style via a private chauffeur car service or embark on an unforgettable aerial journey via helicopter over Sydney, with stunning vistas as you cross the Greater Blue Mountains. PRIVATE TRANSFERS BY CAR Evoke and Unity Executive Services offer private transfers with flexible Sydney CBD or airport meeting points and departure times. Evoke Via Katoomba (Direct to Resort) Head towards the mountains and enjoy a quick stop at Hydro Majestic Pavilion Cafe with views over the Megalong Valley. The journey will then continue through the quaint township of Lithgow before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Tour to Resort) A relaxed transfer with a leisurely stop in the historic township of Katoomba. Enjoy a leisurely self-guided walk to the view the Three Sisters and experience the Jamison Valley. Take an excursion on the panoramic scenic railway at Scenic World (tickets additional). Transfer option includes two-hour stop. Unity Executive Services Via Bells Line of Road (Direct to Resort) Depart Sydney and connect with the picturesque Bells Line of Road to the northwest of Sydney. Travel through the mountains and pass quaint villages, apple orchards, as well as the townships of Bell and Lithgow, before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Stop to Resort) This sightseeing journey begins as you head towards the mountains. Travelling to the township of Katoomba, stop at Cafe 88 to view the famous Three Sisters rock formation. -

TRANSFERS 1 January 2021 - 31 March 2022

TRANSFERS 1 January 2021 - 31 March 2022 Emirates One&Only Wolgan Valley is located approximately 190 kilometres or a three-hour drive from Sydney in the World Heritage-listed Greater Blue Mountains region. Guests can arrive to the resort in style via a private chauffeur car service or embark on an unforgettable aerial journey via helicopter over Sydney, with stunning vistas as you cross the Greater Blue Mountains. PRIVATE TRANSFERS BY CAR Evoke and Unity Executive Services offer private transfers with flexible Sydney CBD or airport meeting points and departure times. Evoke Via Katoomba (Direct to Resort) Head towards the mountains and enjoy a quick stop at Hydro Majestic Pavilion Cafe with views over the Megalong Valley. The journey will then continue through the quaint township of Lithgow before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Tour to Resort) A relaxed transfer with a leisurely stop in the historic township of Katoomba. Enjoy a leisurely self-guided walk to the view the Three Sisters and experience the Jamison Valley. Take an excursion on the panoramic scenic railway at Scenic World (tickets additional). Transfer option includes two-hour stop. Unity Executive Services Via Bells Line of Road (Direct to Resort) Depart Sydney and connect with the picturesque Bells Line of Road to the northwest of Sydney. Travel through the mountains and pass quaint villages, apple orchards, as well as the townships of Bell and Lithgow, before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Stop to Resort) This sightseeing journey begins as you head towards the mountains. Travelling to the township of Katoomba, stop at Cafe 88 to view the famous Three Sisters rock formation. -

The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains Including the Capertee, Coxs, Jenolan & Gurnang Areas

Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains including the Capertee, Coxs, Jenolan & Gurnang Areas Volume 1: Technical Report Hawkesbury-Nepean CMA CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains (including the Capertee, Cox’s, Jenolan and Gurnang Areas) Volume 1: Technical Report (Final V1.1) Project funded by the Hawkesbury – Nepean Catchment Management Authority Information and Assessment Section Metropolitan Branch Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation July 2006 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been completed by the Special thanks to: Information and Assessment Section, Metropolitan Branch. The numerous land owners including State Forests of NSW who allowed access to their Section Head, Information and Assessment properties. Julie Ravallion The Department of Natural Resources, Forests NSW and Hawkesbury – Nepean CMA for Coordinator, Bioregional Data Group comments on early drafts. Daniel Connolly This report should be referenced as follows: Vegetation Project Officer DEC (2006) The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains. Unpublished report funded by Greg Steenbeeke the Hawkesbury – Nepean Catchment Management Authority. Department of GIS, Data Management and Database Environment and Conservation, Hurstville. Coordination Peter Ewin Photos Kylie Madden Vegetation community profile photographs by Greg Steenbeeke Greg Steenbeeke unless otherwise noted. Feature cover photo by Greg Steenbeeke. All Logistics -

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Blue Mountains Region

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Blue Mountains Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright Office of Environment and Heritage on behalf of State of NSW With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs (OEH copyright). The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH). Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Blue Mountains Region Metropolitan and Mountains Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage Department of Premier and Cabinet PO Box 552 Katoomba NSW 2780 Phone: (02) 4784 7300 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 621 5 OEH 2012/0370 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Blue Mountains Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

The Vegetation of the Western Blue Mountains 45 Class

4 DISCUSSION 4.1 PATTERNS IN VEGETATION COMMUNITIES The collection of systematic field data and quantitative multivariate analysis has confirmed that patterns in the composition and distribution of vegetation communities in the study area are influenced by complex interactions between geology, soil type, topography, elevation and rainfall. Different environments distinguish the separate mapping areas, with plant species characterised by those common to either the NSW western slopes, Montane Sydney Sandstone or metamorphic substrates of the Eastern Tableland. The following sections provide an overview of how the changes in environmental characteristics result in corresponding variation in vegetation composition. The sections below represent the breakdown of the dendrogram into broad vegetation groups as described in Section 3.4 (Figure 4), with communities arranged in classes and formations in Keith (2004). Derived Map Units are also related to Tindall et al. (2004) as the Gurnang and Cox’s mapping areas share a common boundary with that work. It should be noted that mapping boundaries will differ between projects given their study was produced at a scale of 1:100 000, which is approximately 16 times coarser than this project, executed at 1:25 000 scale. Consequently, a number of the map units described in that study have been divided when presented here. 4.1.1 Sydney Montane Dry Sclerophyll Forests The Sydney Montane Dry Sclerophyll Forests occupy higher elevation positions (mostly above 900 metres altitude) on sandstones of the Triassic era Narrabeen sediments. These communities defined by Map Units 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30 are characterised by the distinctive sclerophyllous understorey of sandstone environments. -

Conservation Objective: Great Deal of Wading and Rock-Scrambling

Colo Colossus What we do: Friends of the Colo is a volunteer group formed in the year 2000 to control black willows which had infested the of the Colo activities provide a wonderful opportunity to Colo River and some of its tributaries within the Wollemi engage with one of the longest and most spectacular Wilderness. In 2003, when primary control of black willows gorges in Australia, while helping to conserve the pristine in the national park was complete, the group’s attention environment of the area. turned to the control of black and crack willows in those parts of the Colo catchment outside the National Park. In Difficulty: 2003, the group moved on to mapping and treating other Weekend trips involve a bushwalk to and from sites on significant weeds, such as cape ivy, tree of heaven, honey the river. This may include steep tracks or no tracks locust, pampas grass and lantana, along the riparian zone at all, with dents and ascendants of 300 to 500, but in remote areas of the National Park. The primary control inexperienced bushwalkers may be suitable providing of black willows in the catchment was completed in 2006 they are fit. Other activities are up to seven days in and crack willows along the Wolgan River in 2010. length, and are only suitable for those experienced in rugged off-track walking. Walking the river involves a Conservation Objective: great deal of wading and rock-scrambling. To protect the World Heritage Values of the Wollemi National Park, which is part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA), by looking for and treating introduced species whilst on walks or packraft trips in remote areas of the park Conservation with adventure: Much of the group’s work was originally done using white- water rafts after being flown in by helicopter, in a program called WOW (Willows out of Wollemi). -

Wolgan Valley Walk a Guided 3-Day Pack-Free Walk

Wolgan Valley walk A guided 3-day pack-free walk Day 1: Katoomba to Wollemi National Park PRE-TOUR STAY: A pre-tour night at the historic Carrington Hotel can be organised when you book your tour including dinner, bed and breakfast. This art deco manor is in the heart of Katoomba with shops, cafes and restaurants at your doorstep. MEET TIME: Meet time at 8.30am Katoomba TRAIL DETAILS: Walk trail details: Walk: Approximately 11.5kms. 5 hours walking with breaks. Medium grade WALK ITINERARY: Day 1 of our adventures sees us meeting at Carrington Hotel, Katoomba at 8.30am, for our transfer to the start of the walk. We arrive at Wollemi National Park, driving through a series of rock tunnels which seemingly transport us into another world. Our guide explains the route ahead before we set out through a landscape of tall eucalypt forest with Blue Mountains Ash, spectacular pagoda rock formations, vibrant ferns, canyons and streams. We arrive at the entrance to a cave-like tunnel, from here we walk under the mountain range, taking a fascinating short cut to the Wolgan Valley and the beautiful Gardens of Stone National Park. We descend into the darkness with our trusty torch in hand, stopping halfway to turn off our torches and be amazed by the thousands of Glow Worms which transform the tunnel into a starry night. Though natural looking from its exterior appearance, this tunnel is actually a disused railway line, which once descended into the Newnes valley, transporting oil shale. We emerge on the far side of the tunnel greeted by a grove of tree ferns and sheer vertical cliffs towering over 600 feet high. -

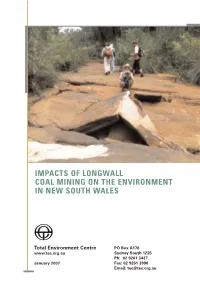

Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on the Environment in New South Wales

IMPACTS OF LONGWALL COAL MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT IN NEW SOUTH WALES Total Environment Centre PO Box A176 www.tec.org.au Sydney South 1235 Ph: 02 9261 3437 January 2007 Fax: 02 9261 3990 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 01 OVERVIEW 3 02 BACKGROUND 5 2.1 Definition 5 2.2 The Longwall Mining Industry in New South Wales 6 2.3 Longwall Mines & Production in New South Wales 2.4 Policy Framework for Longwall Mining 6 2.5 Longwall Mining as a Key Threatening Process 7 03 DAMAGE OCCURRING AS A RESULT OF LONGWALL MINING 9 3.1 Damage to the Environment 9 3.2 Southern Coalfield Impacts 11 3.3 Western Coalfield Impacts 13 3.4 Hunter Coalfield Impacts 15 3.5 Newcastle Coalfield Impacts 15 04 LONGWALL MINING IN WATER CATCHMENTS 17 05 OTHER EMERGING THREATS 19 5.1 Longwall Mining near National Parks 19 5.2 Longwall Mining under the Liverpool Plains 19 5.3 Longwall Top Coal Caving 20 06 REMEDIATION & MONITORING 21 6.1 Avoidance 21 6.2 Amelioration 22 6.3 Rehabilitation 22 6.4 Monitoring 23 07 KEY ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24 7.1 The Approvals Process 24 7.2 Buffer Zones 26 7.3 Southern Coalfields Inquiry 27 08 APPENDIX – EDO ADVICE 27 EDO Drafting Instructions for Legislation on Longwall Mining 09 REFERENCES 35 We are grateful for the support of John Holt in the production of this report and for the graphic design by Steven Granger. Cover Image: The now dry riverbed of Waratah Rivulet, cracked, uplifted and drained by longwall mining in 2006.