Looking Back on the Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO

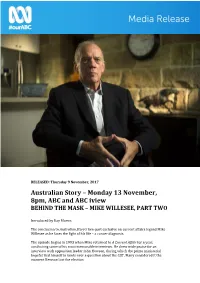

RELEASED: Thursday 9 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO Introduced by Ray Martin. The conclusion to Australian Story’s two-part exclusive on current affairs legend Mike Willesee as he faces the fight of his life – a cancer diagnosis. The episode begins in 1993 when Mike returned to A Current Affair for a year, conducting some of his most memorable interviews. He drew wide praise for an interview with opposition leader John Hewson, during which the prime ministerial hopeful tied himself in knots over a question about the GST. Many considered it the moment Hewson lost the election. Four weeks later praise turned to condemnation when Mike interviewed two young children held captive by killers during the Cangai siege. “I think this is a classic case where we misjudged the audience reaction,” admits former Nine news chief Peter Meakin. Tiring of nightly current affairs, Mike turned his attention to a variety of business interests and documentary making. While in Kenya on his way to film in Sudan he had a premonition that the small plane he was boarding would crash. Shortly after take-off, it did. Although Mike was unhurt, the experience had a profound impact on him and led him on a long journey back to the Catholic faith of his childhood. In the years since he has invested much of his time into trying to find scientific proof for various religious miracles. It is Mike’s strong religious faith, along with the support of his family, that has helped him since being diagnosed with cancer in October last year. -

Newsletter Mar 2007

NEWSLETTER World’s Leading Economist, World Vision CEO Talk Poverty NEWS A large audience was on hand at the nal thinker promoting innovative but offices of Clayton Utz in February to research based ways of alleviating the hear Professor Jeffrey Sachs and Tim plight of extreme poverty". FLASH Costello discuss solutions to the Professor Sachs has worked as a con- world’s poverty crisis. sultant for many countries, including Professor Sachs, director of the Earth Bolivia, Poland, China and Tanzania Institute at Columbia University, has and he discussed many of his experi- Dalai Lama been labelled by the New York Times ences in those countries. In particular, “the most important economist in the he addressed the concept of the world” for his groundbreaking work “ladder of opportunity”, which the to deliver on poverty in developing countries. He poorest countries must get one foot appeared via satellite from New York on in order to begin to develop. and was introduced by Tim Costello In his introduction, Mr Costello stated public lecture AO, head of World Vision Australia. at Castan Centre, 8 June 2007. See page 3 for details. The Castan Centre was established by the Monash University Law Tim Costello AO introduces Jeffrey Sachs on the big screen. School in 2000 as an independent, non-profit organisation committed Because of time differences, the event that, whereas Bono and Bob Geldof to the protection and promotion of was held prior to work and Clayton are the heart of the global poverty human rights. Utz provided a breakfast for the event, movement, “the heart would be noth- which was fully subscribed within ing if there wasn’t the head and I re- Through research and public edu- hours of being announced in Decem- gard Jeffrey Sachs and his thinking, his cation, the Centre generates inno- ber. -

Melissa Doyle AM

Melissa Doyle AM News Presenter, Co-host, MC Melissa Doyle is one of the best-known and trusted voices and faces of Australian media. A highly successful journalist with more than 30 years’ experience, Melissa has been nominated for multiple Silver Logies as Most Popular Television Presenter, voted one of the ‘most real celebrity mums’ and regularly polls in the top 50 of Readers’ Digest’s Most Trusted. In 2016, Melissa was made a Member of the Order of Australia, recognising her “significant service to the community through representational roles with a range of charitable groups, and to the broadcast media”. Talented, smart and warm-hearted, Melissa is an exceptional host and MC for corporate and community events. More about Melissa Doyle: Melissa graduated from Charles Sturt University with a degree in Broadcast Journalism, before beginning her career as a television news reporter and weather presenter at WIN TV Canberra in 1990. Three years later she moved to Prime TV in Canberra as a reporter and co-host of the evening news. In 1995, Melissa joined the Seven Network in the Canberra bureau at Parliament House before moving to the Sydney newsroom. Melissa joined Sunrise in 1997 and co-hosted Australia’s favourite breakfast program until August 2013, taking it from humble beginnings to Number One. During that time, Melissa covered significant events including the Beaconsfield mine disaster, the Royal Wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton, Olympic Games in Sydney, Athens, Beijing and London, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, the Queensland floods, Victoria’s Black Saturday bushfires, multiple federal and state elections, the Inauguration of Barack Obama and the election of Pope Francis. -

Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE

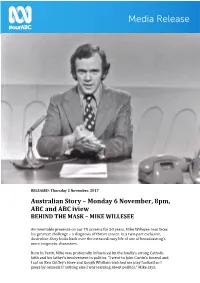

RELEASED: Thursday 2 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE An inimitable presence on our TV screens for 50 years, Mike Willesee now faces his greatest challenge – a diagnosis of throat cancer. In a two-part exclusive, Australian Story looks back over the extraordinary life of one of broadcasting’s more enigmatic characters. Born in Perth, Mike was profoundly influenced by the family’s strong Catholic faith and his father’s involvement in politics. “I went to John Curtin’s funeral and I sat on Ben Chifley’s knee and Gough Whitlam watched me play football so I guess by osmosis if nothing else I was learning about politics,” Mike says. As a 10-year-old, Mike was sent briefly to the notorious Bindoon Boy’s Town by his father in order to toughen him up. It was a brutal experience. “I still don't know why my father thought I needed to toughen up,” Mike says, “but I did toughen up. You know, it changed me.” Later, a split within the Labor party saw the family ostracised by the Catholic church. His father was railed against from the pulpit and Mike was forced out of school a year early by the Catholic brothers who taught him. These events, and an emerging interest in girls, saw Mike turn his back on the church. After school, Mike fell into journalism, working for papers in Perth and Melbourne before ending up in Canberra. When the ABC launched the ground- breaking current affairs program This Day Tonight, he found himself in the right place at the right time. -

Tanami Desert 1

Tanami Desert 1 Tanami Desert 1 (TAN1 – Tanami 1 subregion) GORDON GRAHAM SEPTEMBER 2001 Subregional description and The Continental Stress Class for TAN1 is 5. biodiversity values Known special values in relation to landscape, ecosystem, species and genetic values Description and area There are no known special values within TAN1. Mainly red Quaternary sandplains overlying Permian and Proterozoic strata that are exposed locally as hills and Existing subregional or bioregional plans and/or ranges. The sandplains support mixed shrub steppes of systematic reviews of biodiversity and threats Hakea spp., desert bloodwoods, Acacia spp. and Grevillea spp. over soft spinifex (Triodia pungens) hummock The CTRC report in 1974 (System 7) formed the basis grasslands. Wattle scrub over soft spinifex (T. pungens) of the Department’s publication “Nature Conservation hummock grass communities occur on the ranges. Reserves in the Kimberley” (Burbidge et al. 1991) which Alluvial and lacustrine calcareous deposits occur has itself been incorporated in a Departmental Draft throughout. In the north they are associated with Sturt Regional Management Plan (Portlock et al. 2001). These Creek drainage, and support ribbon grass (Chrysopogon reports were focused on non-production lands and those spp.) and Flinders grass (Iseilema spp.) short-grasslands areas not likely to be prospective for minerals. Action often as savannas with river red gum. The climate is arid statements and strategies in the draft regional tropical with summer rain. Subregional area is 3, 214, management plan do not go to the scale of subregion or 599ha. even bioregion. Dominant land use Apart from specific survey work there has been no systematic review of biodiversity but it is apparent that The dominant land use is (xi) UCL and Crown reserves there are on-going changes to the status of fauna (see Appendix B, key b). -

PRINCESS PARROT Polytelis Alexandrae

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory PRINCESS PARROT Polytelis alexandrae Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Princess parrot. ( Kay Kes Description Conservation reserves where reported: The princess parrot is a very distinctive bird The princess parrot is not resident in any which is slim in build, beautifully plumaged conservation reserve in the Northern and has a very long, tapering tail. It is a Territory but it has been observed regularly in medium-sized parrot with total length of 40- and adjacent to Uluru Kata Tjuta National 45 cm and body mass of 90-120 g. The basic Park, and there is at least one record from colour is dull olive-green; paler on the West MacDonnell National Park. underparts. It has a red bill, blue-grey crown, pink chin, throat and foreneck, prominent yellow-green shoulder patches, bluish rump and back, and blue-green uppertail. Distribution This species has a patchy and irregular distribution in arid Australia. In the Northern Territory, it occurs in the southern section of the Tanami Desert south to Angas Downs and Yulara and east to Alice Springs. The exact distribution within this range is not well understood and it is unclear whether the species is resident in the Northern Territory. Few locations exist in the Northern Territory where the species is regularly seen, and even Known locations of the princess parrot. then there may be long intervals (up to 20 years) between records. Most records from = pre 1970; • = post 1970. the MacDonnell Ranges bioregion are during dry periods. For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au Ecology • extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2007World Vision Australia 02 World Vision Australia Mission To be a Christian organisation that engages people to eliminate poverty and its causes. Vision Our vision for every child, life in all its fullness. Our prayer for every heart, the will to make it so. Values We are committed to the poor We value people We are stewards We are partners We are responsive We are Christian Our relationship with the World Vision International Partnership World Vision Australia is part of the World Vision International Partnership which operates in 97 countries. It is a partnership of interdependent national offices, most of which are governed by local boards or advisory councils. By signing the World Vision International Covenant of Partnership, each partner office agrees to abide by common policies and standards. Partners hold each other accountable through an ongoing system of peer review. Overseas programs are implemented in collaboration with the network of national offices and under the oversight of the World Vision International Partnership, which co-ordinates activities such as the transfer of funds and strategic operations. Whilst we are accountable to other World Vision offices, World Vision Australia is a distinct legal entity. Together with our partner offices, we are responsible for the design, monitoring and evaluation of all programs for which we provide funding. Fundraising and marketing activities are managed locally here in Australia. An international Board of Directors oversees the World Vision International Partnership. The full Board, which meets twice a year, appoints the Partnership’s senior officers, approves strategic plans and budgets, and determines international policy. -

Stephen Harrington Thesis

PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE BEYOND JOURNALISM: INFOTAINMENT, SATIRE AND AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION STEPHEN HARRINGTON BCI(Media&Comm), BCI(Hons)(MediaSt) Submitted April, 2009 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia 1 2 STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made. _____________________________________________ Stephen Matthew Harrington Date: 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationships between television, politics, audiences and the public sphere. Premised on the notion that mediated politics is now understood “in new ways by new voices” (Jones, 2005: 4), and appropriating what McNair (2003) calls a “chaos theory” of journalism sociology, this thesis explores how two different contemporary Australian political television programs (Sunrise and The Chaser’s War on Everything) are viewed, understood, and used by audiences. In analysing these programs from textual, industry and audience perspectives, this thesis argues that journalism has been largely thought about in overly simplistic binary terms which have failed to reflect the reality of audiences’ news consumption patterns. The findings of this thesis suggest that both ‘soft’ infotainment (Sunrise) and ‘frivolous’ satire (The Chaser’s War on Everything) are used by audiences in intricate ways as sources of political information, and thus these TV programs (and those like them) should be seen as legitimate and valuable forms of public knowledge production. -

The Fall of Sai Gon 30 April 1975

WALL NOTE TWO: THE FALL OF SAI GON 30 APRIL 1975 DANIEL R. ARANT [email protected] DATE OF INFORMATION: 06 MAY 2008 "We must ensure that any major foreign policy commitment has the full support and understanding of the American people....." GEORGE H. W. BUSH, 41st President of the United States. "The American soldiers who fought in the war did so out of a sense of duty to their country, but their country betrayed them by sending them to an unconscionable war." PHILIP CAPUTO, U.S. Marine infantry platoon leader in Viet Nam and author of A Rumor of War. "... the leaders who planned and executed the war did not understand what they were getting into. The values and ideals we stood for were correct, but it was the wrong war in the wrong place - a place we did not know." RICHARD HOLBROOKE, Foreign Service diplomat in Viet Nam. "Those Americans who went to Vietnam fought for freedom, a truly noble cause. This battle was lost not by those brave Americans and South Vietnamese troops who were waging it but by political misjudgments and strategic failure at the highest levels of government." RONALD REAGAN, 40th President of the United States. "The Vietnam War was a political war that imposed restraints on the military that prevented use of power that we had readily available. ... it was very difficult to tell friend from foe, hence the Calley affair." ADM. THOMAS H. MOORER, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1970-1974). "It was a disastrous, insane, imperial invasion of a weirdo Third World country." TIMOTHY LEARY. -

1991 Collegian

it*. , . J ‘ *"■ Ky.' ' 'w^w»SE:r. *:m8§§i ^feJlPP PMMMS IK* ,;U . -.V'* ■■ :. mm fmgmm >- * . * ' aBeSflft ‘%v’ i . iinHP? 'w* Up (f|is sJSfikii'Sf'i J*^®**^ | «>. >i CP 4 ‘ ' 'f'-:irW'y 'i > '-tv * '' -* «**«*#•’*■ .-■'*■*'*! wfcWwjf *•> • ,4t, *' . •** mm P ■ V-a.f’,' ? && MlililNHHHHBiSilHH m iCffiiBiHiiil EDITORIAL With aspirations to become the next Nancy Wake, Phillip Adams and Miriam Borthwick the Collegian Committee began mm its gruelling task of producing this wondrous manuscript. At the beginning our naiviety led us to believe that reports miraculously land in the ‘in’ file, photos are taken by themselves and the final magazine arrives in all its splendour out of thin air. After two weeks, this illusory belief was shattered, thanks to Mrs. Shepherd’s constant reminders and imposed deadlines, the Collegian Committee set about performing its actual task. People owning reports were hounded and harassed (by the secret Collegian Force) photography sessions were ruled with an iron fist and the school body was subjected to the revolutionary 'A-:-- torture, technique of Collegian Committee advertising (thanks Mrs. Pyett for the loan of your sunnies). Through these trials and tribulations the Collegian Committee has brought about several changes as you will no doubt notice. We hope that these alterations improve the overall effect of the 1991 Collegian. Finally as the year draws to an end, I would like to thank Mrs. Shepherd plus Mr. Thompson for their invaluable help and the entire Collegian Committee for their tireless work. I am sure that they’d all agree that working on the Collegian was a rewarding and enjoyable experience. -

Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam (「救済劇場」:合衆国によるベトナム 撤退の文化表象)

Ayako Sahara Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam (「救済劇場」:合衆国によるベトナム 撤退の文化表象) Ayako Sahara* SUMMARY IN JAPANESE: 本論文は、イラク撤退に関して 再び注目を集めたベトナム人「救済」が合衆国の経済的・軍 事的・政治的パワーを維持する役割を果たしてきたと考察し、 ベトナム人救済にまつわる表象言説を批判的に分析する。合 衆国のベトナムからの撤退が、自国と同盟国の扱いをめぐる 「劇場」の役割をいかに果たしたのかを明らかにすることを その主眼としている。ここで「劇場」というのは、撤退が単 一の歴史的出来事であっただけではなく、その出来事を体験 し目撃した人々にとって、歴史と政治が意味をなす舞台とし て機能したことを問うためである。戦争劇場は失敗に終わっ たが、合衆国政府が撤退作戦を通じて、救済劇を立ち上げた ことの意味は大きい。それゆえ、本論文は、従来の救済言説 に立脚せず、撤退にまつわる救済がいかにして立ち上がり、 演じられ、表象されたかを「孤児輸送作戦」、難民輸送と中 央情報局職員フランク・スネップの回想録を取り上げて分析 する。 * 佐原 彩子 Lecturer, Kokushikan University, Tokyo and Dokkyo University, Saitama, Japan. 55 Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam It wasn’t until months after the fall of Saigon, and much bloodshed, that America conducted a huge relief effort, airlifting more than 100,000 refugees to safety. Tens of thousands were processed at a military base on Guam, far away from the American mainland. President Bill Clinton used the same base to save the lives of nearly 7,000 Kurds in 1996. But if you mention the Guam Option to anyone in Washington today, you either get a blank stare of historical amnesia or hear that “9/11 changed everything.”1 Recently, with the end of the Iraq War, the memory of the evacuation of Vietnamese refugees at the conclusion of the Vietnam War has reemerged as an exceptional rescue effort. This perception resonates with previous studies that consider the admission of the refugees as “providing safe harbor for the boat people.”2 This rescue narrative has been an integral part of U.S. power, justifying its military and political actions. In response, this paper challenges the perception of the U.S. as rescuing allies. -

China's Year in Review

2017 China's Year in Review Follow China Intercontinental Press Us on Advertising Hotline WeChat Now 城市漫步珠 国内统一刊号: 三角英文版 that's guangzhou that's shenzhen CN 11-5234/GO JANUARY 2018 01月份 that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Senior Digital Editor Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Editor Adam Robbins Guangzhou Editor Daniel Plafker Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang Digital Editor Katrina Shi National Arts Editor Erica Martin Contributors Ned Kelly, Betty Richardson, Lena Gidwani, Dr. Adam Koh, Mia Li, Katrina Shi, Dominic Ngai, Erica Martin, Dominique Wong, Bryan Grogan, Kheng Swe Lim, Paul Barresi, Sky Gidge HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 : 100027 9G, Block C, Ginza Mall, No.