Notes on the Silviculture of Major Nsw Forest Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TML Propagation Protocols

PROPAGATION PROTOCOLS This document is intended as a guide for Tamborine Mountain Landcare members who wish to assist our regeneration projects by growing some of the plants needed. It is a work in progress so if you have anything to add to the protocols – for example a different but successful way of propagating and growing a particular plant – then please give it to Julie Lake so she can add it to the document. The idea is that our shared knowledge and experience can become a valuable part of TML's intellectual property as well as a useful source of knowledge for members. As there are many hundreds of plants native to Tamborine Mountain, the protocols list will take a long time to complete, with growing information for each plant added alphabetically as time permits. While the list is being compiled by those members with competence in this field, any TML member with a query about propagating a particular plant can post it on the website for other me mb e r s to answer. To date, only protocols for trees and shrubs have been compiled. Vines and ferns will be added later. Fruiting times given are usual for the species but many rainforest plants flower and fruit opportunistically, according to weather and other conditions unknown to us, thus fruit can be produced at any time of year. Finally, if anyone would like a copy of the protocols, contact Julie on [email protected] and she’ll send you one. ………………….. Growing from seed This is the best method for most plants destined for regeneration projects for it is usually fast, easy and ensures genetic diversity in the regenerated landscape. -

Diet of the White-Headed Pigeon Columba Leucomela Near Lismore, Northern New South Wales: Fruit, Seeds, Flower Buds, Bark and Grit

Corella, 2011, 35(3): 107-111 Diet of the White-headed Pigeon Columba leucomela near Lismore, northern New South Wales: fruit, seeds, flower buds, bark and grit D. G. Gosper 39 Azure Avenue, Balnarring, Victoria 3926, Australia Received: 27 May 2010 Gut contents of 18 White-headed Pigeons Columba leucomela, found dead over a four-year period near Lismore in northern New South Wales, comprised fruits and seeds of the invasive plant Camphor Laurel Cinnamomum camphora almost exclusively. Birds frequently ingested Melaleuca quinquenervia bark, which, as far as I am aware, constitutes the fi rst record of consumption of bark in the Columbidae, prompting some interesting hypotheses. It is suggested that bark ingestion may counter potential adverse effects from a diet dominated by Camphor Laurel fruits and seeds, which are reputed to contain toxins. Incidental records of consumption of fl ower buds of indigenous plants and insects (the fi rst such records for this species), and regular drinking from man-made structures such as roof guttering on buildings are detailed. INTRODUCTION surrounding area is a mixture of pasture, remnant riparian rainforest and regrowth forest with extensive areas dominated The White-headed Pigeon Columba leucomela is known to by woody weed species, notably Camphor Laurel and Broad- feed on the fruits and seeds of a number of fl eshy-fruited invasive leaved Privet Ligustrum lucidum, and several house gardens. plants, notably Camphor Laurel Cinnamomum camphora, which has become an important seasonal food source for this species Dead pigeons were collected and crop and gizzard contents in northern New South Wales (NSW) (Frith 1982; Recher and removed during subsequent dissection. -

Newsletter for Landcare and Dunecare in Byron Shire

Newsletter for Landcare and Dunecare in Byron Shire http://www.brunswickvalleylandcare.org.au/ September 2019 Completion of National Landcare Grant in Yalla Kool Reserve by Alison Ratcliffe The project which has allowed Brunswick Valley Landcare and the volunteers of Yalla Kool Landcare group to upgraded the walking track through Yalla Kool Reserve in Ocean Shores is now complete. The project has been a great success with 3 community days with 92 attendees, 0.5 ha of regeneration and planting of 420 plants as well as the significant improvement to the walking track. Yalla Kool Reserve was successful in receiving $49,816 through the Australian Governments National Landcare Program Environments Small Grants to improve the condition and function of this suburban reserve in Ocean Shores. Alison Ratcliffe, Landcare Support Officer said “The project has allowed the walking track to be upgraded and formalised. The walking track that winds through the reserve is now accessible in all weathers. It provides a great link between the Ocean Shores shopping centre and Devine’s Hill lookout through a beautiful natural environment”. These photos show the difference from the start of the project in September 2018 to this week. This project has been supported by funding from the Australian Governments National Landcare Program. 1 For the full program https://www.bigscrubrainforest.org/big-scrub-rainforest-day/ 2 Locally Brunswick Valley Landcare are holding guided Rainforest Identification walks through Heritage Park – Maslam Arboretum in Mullumbimby. To book on any or all of the 3 walks please visithttps://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/big-scrub- rainforest-day-guided-walks-and-talks-tickets- 68921531155 Weed Identification Walk Thursday 26th September at 10am-12noon David Filipczyk, Byron Shire Council Bush Regenerator, will lead a weed walk along the Byron Shire Council managed site on Casuarina St starting from St John's Primary School carpark. -

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan Working Plan for Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3 Upper North East Forest Agreement Region North East Region Contents Page 1. DETAILS OF THE RESERVE 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Location 2 1.3 Key Attributes of the Reserve 2 1.4 General Description 2 1.5 History 6 1.6 Current Usage 8 2. SYSTEM OF MANAGEMENT 9 2.1 Objectives of Management 9 2.2 Management Strategies 9 2.3 Management Responsibility 11 2.4 Monitoring, Reporting and Review 11 3. LIST OF APPENDICES 11 Appendix 1 Map 1 Locality Appendix 1 Map 2 Cadastral Boundaries, Forest Types and Streams Appendix 1 Map 3 Vegetation Growth Stages Appendix 1 Map 4 Existing Occupation Permits and Recreation Facilities Appendix 2 Flora Species known to occur in the Reserve Appendix 3 Fauna records within the Reserve Y:\Tourism and Partnerships\Recreation Areas\Orara East SF\Bruxner Flora Reserve\FlRWP_Bruxner.docx 1 Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan 1. Details of the Reserve 1.1 Introduction This plan has been prepared as a supplementary plan under the Nature Conservation Strategy of the Upper North East Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management (ESFM) Plan. It is prepared in accordance with the terms of section 25A (5) of the Forestry Act 1916 with the objective to provide for the future management of that part of Orara East State Forest No 536 set aside as Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3. The plan was approved by the Minister for Forests on 16.5.2011 and will be reviewed in 2021. -

5. Aboriginal Context

5. ABORIGINAL CONTEXT 5.1 Tribal boundaries The two major tribal groups in the Wells Crossing to Iluka Road project area are the Gumbainggar and the Yaygir. Tindale (1940) places a Kumbainggiri (Gumbainggar) tribe in the area from the headwaters of the Nymboida River across the range to Urunga, Coffs Harbour, Bellingen, Glenreagh and Grafton. The Gumbainggar tribe spoke a language belonging to the Kumbainggeric Group. As this tribal group covered such a large, environmentally diverse area it is probable that the language contained three or four dialects. The large territory may have supported a population of between 1,200 and 1,500 people (Hoddinott 1978). The boundary between this group and the Yaygir (Jiegera) to the east is difficult to establish. While Tindale (1974) places the Yaygir downstream from Grafton from the south bank of the Clarence west to Cowper and south to Wooli, Heron (1991), after oral research, placed the boundary from Corindi Beach north to Black Rocks and taking in Ulmarra in the west. In contrast to the Gumbainggar, the Yaygir covered a small area, but the availability of resources both from the ocean and the Clarence River meant that the area could support a larger population. Byrne (1985) estimated a population density of 6 people to 2 km², giving a total population of 800 before white settlement. These areas are bounded to the north by the Badjelong (Bandjalong) and to the south by the Dangaddi tribal groups. 5.2 Previous archaeological studies in the region Although archaeological research has been carried out in the Coffs Harbour-Grafton region of NSW for a number of years, very little research has been conducted in the Yamba area. -

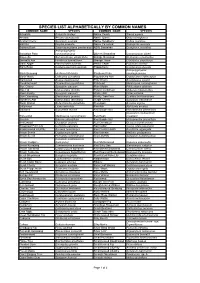

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

(Phascolarctos Cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales

A Blueprint for a Comprehensive Reserve System for Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales Ashley Love (President, NPA Coffs Harbour Branch) & Dr. Oisín Sweeney (Science Officer, NPA NSW) April 2015 1 Acknowledgements This proposal incorporates material that has been the subject of years of work by various individuals and organisations on the NSW north coast, including the Bellengen Environment Centre; the Clarence Environment Centre; the Nambucca Valley Conservation Association Inc., the North Coast Environment Council and the North East Forest Alliance. 2 Traditional owners The NPA acknowledges the traditional Aboriginal owners and original custodians of the land mentioned in this proposal. The proposal seeks to protect country in the tribal lands of the Bundjalung, Gumbainggir, Dainggatti, Biripi and Worimi people. Citation This document should be cited as follows: Love, Ashley & Sweeney, Oisín F. 2015. A Blueprint for a comprehensive reserve system for koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales. National Parks Association of New South Wales, Sydney. 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Traditional owners ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Citation ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

North East Forest Alliance Submission to Inquiry Into the Australian Forestry Industry Dailan Pugh, North East Forest Alliance, March 2011

North East Forest Alliance submission to Inquiry into the Australian forestry industry Dailan Pugh, North East Forest Alliance, March 2011 This submission addresses aspects of the following terms of reference of your committee: 1. Opportunities for and constraints upon production ................................................................ 5 1.1. Regional Forest Agreements ........................................................................................... 5 1.1.1. Satisfaction of Criteria ............................................................................................. 8 1.1.2. The Process is a Sham ............................................................................................ 10 1.2. Sustainable Yield ........................................................................................................... 18 1.2.1 Coming to Grips with Sustainability ....................................................................... 24 1.2.2. Yield Shortfalls ...................................................................................................... 30 2. Environmental impacts of forestry ....................................................................................... 34 2.1. Ecosystems ................................................................................................................... 37 2.2. Threatened Species ........................................................................................................ 39 2.2.1. Compartment Mark Up ......................................................................................... -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 29 Friday, 6 February 2009 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

559 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 29 Friday, 6 February 2009 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Announcement Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Following the commencement of the remaining provisions of the Interpretation Amendment Act 2006, the following statutory instruments are to be notified on the official NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) instead of being published in the Gazette: (a) all environmental planning instruments, on and from 26 January 2009, (b) all statutory instruments drafted by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and made by the Governor (mainly regulations and commencement proclamations) and court rules, on and from 2 March 2009. Instruments for notification on the website are to be sent via email to [email protected] or fax (02) 9232 4796 to the Parliamentary Counsel's Office. These instruments will be listed on the “Notification” page of the NSW legislation website and will be published as part of the permanent “As Made” collection on the website and also delivered to subscribers to the weekly email service. Principal statutory instruments also appear in the “In Force” collection where they are maintained in an up-to-date consolidated form. Notified instruments will also be listed in the Gazette for the week following notification. For further information about the new notification process contact the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office on (02) 9321 3333. 560 LEGISLATION 6 February 2009 Proclamations New South Wales Proclamation under the Brigalow and Nandewar Community Conservation Area Act 2005 MARIE BASHIR,, Governor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, CVO, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 16 (1) of the Brigalow and Nandewar Community Conservation Area Act 2005, do, by this my Proclamation, amend that Act as set out in Schedule 1. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

ASIC 24A/03, Tuesday, 17 June 2003 Published by ASIC

= = `çããçåïÉ~äíÜ=çÑ=^ìëíê~äá~= = Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 24A/03, Tuesday, 17 June 2003 Published by ASIC ^^ppff``==dd~~òòÉÉííííÉÉ== Contents Life Insurance Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2002 Specific disclaimer for Special Gazette relating to Life Unclaimed Monies The information in this Gazette is provided by life insurance companies and friendly societies to ASIC pursuant to the Life Insurance Act (Commonwealth) 1995. The information is published by ASIC as supplied by the relevant life insurance company and/or friendly society and ASIC does not add to the information. ASIC does not verify or accept responsibility in respect of the accuracy, currency or completeness of the information, and, if there are any queries or enquiries, these should be made direct to the life insurance company or friendly society. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2002 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 5179AA, Melbourne Vic 3001 Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC Gazette ASIC 24A/03, Tuesday, 17 June 2003 Life Insurance Unclaimed Money Page 2= = Life Insurance Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2002 Section 216 of Life Insurance Act 1995 STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED MONEY UNDER THE LIFE INSURANCE ACT GENERAL INFORMATION Life Insurance Companies Unclaimed Money. In accordance with section 216 of the Life Insurance Act 1995 the list sets out details of unclaimed money of not less than $200.00 which life insurance companies have paid to the Commonwealth Government in respect of the year ended 31 December 2002.