Placing Battlefields: Ontario's War of 1812 Niagara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culturegrams States Edition

Print window Close window The Empire State Established 1788 11th State n The first public miniature golf course was built on the roof of a New York City skyscraper in 1926. n The apple muffin is the official state muffin. n The Empire State Building has 73 elevators. One can take you from the lobby to the 80th floor in 45 seconds. n A Clayton housewife named Sophia LaLonde invented Thousand Island dressing; it is named after the Thousand Islands. n Baseball began in New York. The first baseball game was played in Hoboken on 19 June 1845. n “Uncle Sam” was a meatpacker from Troy. During the War of 1812, Sam Wilson stamped “U.S. Beef” on his products. Soldiers came to think of him as Uncle Sam. n In 1857, Joseph C. Gayetty of New York invented toilet paper. It had his name on every sheet. n Almost one and a half million stray dogs and cats live in the New York City area. n New Yorker Franklin Roosevelt was the only U.S. president to be elected four times. Climate Sunny skies in the Empire State generally are hidden by clouds that form over the Great Lakes. The coast isn't as cloudy or as cold as the rest of the state. Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse get more snow than any other U.S. cities. The Tug Hill Plateau area got over 29 feet (9 m) in one long winter! It rains regularly in the summer. New York is almost always humid, which makes the temperatures seem more extreme. -

Fort Niagara Flag Is Crown Jewel of Area's Rich History

Winter 2009 Fort Niagara TIMELINE The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara Flag The War of 1812 Photo courtesy of Angel Art, Ltd. Lewiston Flag is Crown Ft. Niagara Flag History Jewel of Area’s June 1809: Ft. Niagara receives a new flag Mysteries that conforms with the 1795 Congressional act that provides for 15 starts and 15 stripes Rich History -- one for each state. It is not known There is a huge U.S. flag on display where or when it was constructed. (There were actually 17 states in 1809.) at the new Fort Niagara Visitor’s Center that is one of the most valued historical artifacts in the December 19, 1813: British troops cap- nation. The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara flag is one of only 20 ture the flag during a battle of the War of known surviving examples of the “Stars and Stripes” that were 1812 and take it to Quebec. produced prior to 1815. It is the earliest extant flag to have flown in Western New York, and the second oldest to have May 18, 1814: The flag is sent to London to be “laid at the feet of His Royal High- flown in New York State. ness the Prince Regent.” Later, the flag Delivered to Fort Niagara in 1809, the flag is older than the was given as a souvenir to Sir Gordon Star Spangled Banner which flew over Ft. McHenry in Balti- Drummond, commander of the British more. forces in Ontario. Drummond put it in his As seen in its display case, it dwarfs home, Megginch Castle in Scotland. -

The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814

Documentary History 9W ttl# ampatgn on tl?e lagara f rontier iMiaM. K«it*«l fisp the Luntfy« Lfluiil "'«'>.,-,.* -'-^*f-:, : THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGN ON THE - NIAGARA FRONTIER IN 1814. EDITED FOR THE LUNDTS LANE HISTORICAL SOCIETY BY CAPT. K. CRUIK8HANK. WELLAND PRINTBD AT THE THIBVNK OKKICB. F-5^0 15 21(f615 ' J7 V.I ^L //s : The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814. LIEVT.COL. JOHN HARVEY TO Mkl^-iiE^, RIALL. (Most Beoret and Confidential.) Deputy Adjutant General's Office, Kingston, 28rd March, 1814. Sir,—Lieut. -General Drummond having had under his con- sideration your letter of the 10th of March, desirinjr to be informed of his general plan of defence as far as may be necessary for your guidance in directing the operations of the right division against the attempt which there is reason to expect will be made by the enemy on the Niagara frontier so soon as the season for operations commences, I have received the commands of the Lieut.-General to the following observations instructions to communicate you and y The Lieut. -General concurs with you as to the probability of the enemy's acting on the ofTensive as soon as the season permits. Having, unfortunately, no accurate information as to his plans of attack, general defensive arrangements can alone be suggested. It is highly probable that independent of the siege of Fort Niagara, or rather in combination with the atttick on that place, the enemy \vill invade the District of Niagara by the western road, and that he may at the same time land a force at Long Point and per- haps at Point Abino or Fort Erie. -

North Country Notes

Clinton County Historical Association North Country Notes Issue #414 Fall, 2014 Henry Atkinson: When the Lion Crouched and the Eagle Soared by Clyde Rabideau, Sn I, like most people in this area, had not heard of ing the same year, they earned their third campaigu Henry Atkinson's role in the history of Plattsburgh. streamer at the Battle of Lundy Lane near Niagara It turns out that he was very well known for serving Falls, when they inflicted heavy casualties against the his country in the Plattsburgh area. British. Atkinson was serving as Adjutant-General under Ma- jor General Wade Hampton during the Battle of Cha- teauguay on October 25,1814. The battle was lost to the British and Wade ignored orders from General James Wilkinson to return to Cornwall. lnstead, he f retreated to Plattsburgh and resigned from the Army. a Colonel Henry Atkinson served as commander of the a thirty-seventh Regiment in Plattsburgh until March 1, :$,'; *'.t. 1815, when a downsizing of the Army took place in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The 6'h, 11'h, 25'h, Brigadier General Henry Atkinson 2'7th, zgth, and 37th regiments were consolidated into Im age courtesy of www.town-of-wheatland.com the 6th Regiment and Colonel Henry Atkinson was given command. The regiment was given the number While on a research trip, I was visiting Fort Atkin- sixbecause Colonel Atkinson was the sixth ranking son in Council Bluffs, Nebraska and picked up a Colonel in the Army at the time. pamphlet that was given to visitors. -

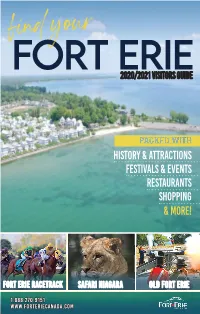

2020/2021 Visitors Guide

2020/2021 Visitors Guide packed with History & Attractions Festivals & Events Restaurants Shopping & more! fort erie Racetrack safari niagara old fort erie 1.888.270.9151 www.forteriecanada.com And Mayor’s Message They’re Off! Welcome to Fort Erie! We know that you will enjoy your stay with us, whether for a few hours or a few days. The members of Council and I are delighted that you have chosen to visit us - we believe that you will find the xperience more than rewarding. No matter your interest or passion, there is something for you in Fort Erie. 2020 Schedule We have a rich history, displayed in our historic sites and museums, that starts with our lndigenous peoples over 9,000 years ago and continues through European colonization and conflict and the migration of United Empire l yalists, escaping slaves and newcomers from around the world looking for a new life. Each of our communities is a reflection of that histo y. For those interested in rest, relaxation or leisure activities, Fort Erie has it all: incomparable beaches, recreational trails, sports facilities, a range of culinary delights, a wildlife safari, libraries, lndigenous events, fishin , boating, bird-watching, outdoor concerts, cycling, festivals throughout the year, historic battle re-enactments, farmers’ markets, nature walks, parks, and a variety of visual and performing arts events. We are particularly proud of our new parks at Bay Beach and Crystal Ridge. And there is a variety of places for you to stay while you are here. Fort Erie is the gateway to Canada from the United States. -

10-2 157410 Volumes 1-7 Open FA 10-2

10-2_157410_volumes_1-7_open FA 10-2 RG Volume Reel no. Title / Titre Dates no. / No. / No. de de bobine volume RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-05-27 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-08-31 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-11-17 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-12-28 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 William Dummer Powell to Peter Russell respecting Joseph Brant 1797-01-05 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Copy of Duke of 1797-04-26 Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, stating that the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada will head the Indian Department, but that the Department will continue to be paid from the military chest - Enclosed: Copy of additional instructions to Lieutenant Governor U.C., 15 December 1796, respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Extract, Duke of Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, respecting Indian Department in U.C. RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell sending a copy of Robert Liston's letter - Enclosed: Copy, 1797-05-18 Robert Liston to Prescott, 22 April 1797, respecting the frontier posts RG10-A-1-a -

Rethinking the Niagara Frontier

Ongoing work in the Niagara Region Next Steps Heritage Development in Western New York The November Roundtable concluded with a lively Rethinking the Niagara Frontier It would be a mistake, however, to say that the process of heritage development has discussion of the prospects for bi-national cooperation European Participants yet to begin here. around issues of natural and cultural tourism and her- itage development. There is no shortage of assets or Michael Schwarze-Rodrian As Bradshaw Hovey of UB’s smaller scale and at a finer grain. Projekt Ruhr GmbH Urban Design Project outlined, He highlighted the case of Fort stories, and there is great opportunity we can seize by Berliner Platz 6-8 A report on the November Roundtable there are initiatives in environ- Erie, one of the smaller commu- working together. Essen, Germany 45127 mental repair, historic preserva- nities in the region, but one that Email: schwarze-rodrian@projek- tion, infrastructure investment, rightfully lays claim to the title of Some identified the need to truhr.de economic development, and cul- “gateway to Canada.” broaden and deepen grassroots November 20, 2000 tural interpretation ongoing from What Fort Erie has done is rel- involvement, while others zeroed Christian Schützinger one end of the region to the atively simple. They have in on the necessity of engaging Bodensee-Alpenrhein Tourismus other. matched local assets with eco- leadership at higher levels of gov- Focus on heritage Bethlehem Steel Plant Postfach 16 In Buffalo, work is proceeding Source: Patricia Layman Bazelon nomic trends and community ernment and business. There was A-6901 Bregenz, Austria To develop the great bi-national region that spans the Niagara River, we should on the redevelopment of South goals to identify discrete areas of a great deal of discussion about Email: c.schuetzinger@bodensee- Buffalo “brownfields”; aggressive works; and a cultural tourism desired investment. -

Monuments and Memories in Ontario, 1850-2001

FORGING ICONOGRAPHIES AND CASTING COLONIALISM: MONUMENTS AND MEMORIES IN ONTARIO, 1850-2001 By Brittney Anne Bos A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September 2016) Copyright ©Brittney Anne Bos, 2016 ii Abstract Commemorations are a critical window for exploring the social, political, and cultural trends of a specific time period. Over the past two centuries, the commemorative landscape of Ontario reaffirmed the inclusion/exclusion of particular racial groups. Intended as static markers to the past, monuments in particular visually demonstrated the boundaries of a community and acted as ongoing memorials to existing social structures. Using a specific type of iconography and visual language, the creators of monuments imbued the physical markers of stone and bronze with racialized meanings. As builders were connected with their own time periods and social contexts, the ideas behind these commemorations shifted. Nonetheless, creators were intent on producing a memorial that educated present and future generations on the boundaries of their “imagined communities.” This dissertation considers the carefully chosen iconographies of Ontario’s monuments and how visual symbolism was attached to historical memory. Through the examination of five case studies, this dissertation examines the shifting commemorative landscape of Ontario and how memorials were used to mark the boundaries of communities. By integrating the visual analysis of monuments and related images, it bridges a methodological and theoretical gap between history and art history. This dissertation opens an important dialogue between these fields of study and demonstrates how monuments themselves are critical “documents” of the past. -

Officers of the British Forces in Canada During the War of 1812-15

J Suxjnp ep-eu'BQ UT aqq. jo sjaoijjo II JC-B.IJUIOH 'i SUTAJI n Auvuan oiNOHOi do 13>IDOd SIH1 lAIOUd SdHS HO SQdVD 3AOIAI3d ION 00 3SV31d r? 9 VlJVf .Si Canadian Military Institute OFFICERS OF THE British Forces in Canada DURING THE WAR OF 1812=15 BY HOMFRAY IRVING, Honorary librarian. WETLAND TRIBUNE PRINT. 1908 ~* u u Gin co F>. Year Nineteen Hundred and Entered According to Act of Parliament, in the in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture. Eight, by L. Homfray Irving, INTRODUCTION " A which takes no in the noble " people pride achievements of remote ancestors will never "achieve anything worthy to be remembered "with pride by remote descendants." Macaulay's History of England. The accompanying lists of officers, who served during the war of 1812-15, are compiled from the records of the grants of land made in Upper Canada to officers, non-commissioned officers and men who had served in "the first flank Companies, the Provincial Artillery, the Incorporated Regiment, the Corps of Artillery Drivers, the Provincial Dragoons, the Marine and General Staff of the Army,"* and in Lower Canada, to "the officers and men of the Embodied Militia, discharged troops and others."** All those who participated in the Prince Regent's Bounty, as these land grants were called, are indicated by a star in front of their respective names. The names of those who received land grants as above have been supplemented by names from pay lists, appointments and promotions as published in Militia Orders, returns, petitions and correspondence in the office of the Archivist and Keeper of the Records, Arthur G. -

Underground Railroad in Western New York

Underground Railroad on The Niagara Frontier: Selected Sources in the Grosvenor Room Key Grosvenor Room Buffalo and Erie County Public Library 1 Lafayette Square * = Oversized book Buffalo, New York 14203-1887 Buffalo = Buffalo Collection (716) 858-8900 Stacks = Closed Stacks, ask for retrieval www.buffalolib.org GRO = Grosvenor Collection Revised June 2020 MEDIA = Media Room Non-Fiction = General Collection Ref. = Reference book, cannot be borrowed 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 Books .............................................................................................................................. 2 Newspaper Articles ........................................................................................................ 4 Journal & Magazine Articles .......................................................................................... 5 Slavery Collection in the Rare Book Room ................................................................... 6 Vertical File ..................................................................................................................... 6 Videos ............................................................................................................................. 6 Websites ......................................................................................................................... 7 Further resources at BECPL ......................................................................................... -

History, Facts & Statistics

Other Facilities & Programs The Tourism Council supervises the preparation and placement of paid advertising to stimulate interest in the 1000 Islands Region as a tourist In 1977 the TIBA was gifted the Boldt Castle attraction destination. All advertising includes the toll free phone number (1-800-847- on Heart Island, a major tourist destination in the 5263) and website www.visit1000islands.com to receive direct inquiries. The 1000 Islands region, but a property that had been Travel Guide is sent as the fulfi llment piece to all inquiries received as a result allowed to decline to a state of disrepair. In addition, of these advertisements. the TIBA assumed ownership of the Boldt Castle Yacht House (now open for public visitation) as part of this gift. The TIITC is also very active in preparing news releases to stimulate editorial The TIBA quickly moved on a well-planned repair program to arrest further coverage in newspapers and magazines. Publicity programs, familiarization deterioration and to rehabilitate much of these properties. tours, and festival promotion off er a substantial amount of interest for this program. In 1978, the fi rst year the Authority operated the Boldt Castle attraction, THOUSANDBRIDGE ISLANDS attendance was tallied at 99,000 visitors. With over $35,000,000 in maintenance The TIBA and the FBCL, have long been key players in the promotion of tourism- repairs and major capital improvement projects to this regional attraction, related development, providing benefi ts of tremendous economic welfare to y this region. The TIBA’s Welcome Center houses the offi ces of the TIITC as well r visitations have increased annually – including a one-year, record-breaking a as off ers informational and comfort facilities to the traveling public, located s attendance of 240,000! r e near the US bridge at Collins Landing. -

Self-Guided Walking Tour Park Walking Tour

Point of Interest Lake Ontario Historic Site Self-Guided Walking Tour Park Walking Tour Riverbeach Dr Walking Trail Lockhart St 23 Delater Street Fort Queen’s Royal Park Pumphouse Mississauga Gallery 24 Nelson Street 25 Navy Front Street Ricardo Street End Hall 20 21 22 Melville Street 26 St. Mark’s Church Fort 8 4 3 Start George Prideaux Street Byron Street 1 Niagara-on-the-Lake Golf Club 67 5 Simcoe St. Vincent 9 Park dePaul Church 2 19 18 Queen Street 10 Picton Street Information 17 11 Grace United Church 12 16 15 13 Johnson Street Plato Street Queen’s Parade 14 llington Street We Street treet Niagara vy Street Historical Da te S Museum Ga oria Street Castlereagh Street ct King Street Simcoe Street Regent Vi Mississaugua Street St. Andrew’s Church 1. Fort George: located on the Queen’s Parade at the end of the Niagara Parkway. Here, you will see staff in period costume and uniform re-enacting typical daily life in the garrison prior to the War of 1812 when Fort George was occupied by the British Army. 2. St. Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church, circ. 1834. Niagara’s first Roman Catholic Church. Exit Fort George through the main parking lot, to Queen’s Parade. Turn right and proceed to the corner of Wellington and Picton. 3. St. Mark’s Anglican Church. This churchyard dates from the earliest British settlement. Please see plaque. Turn right onto Wellington Street then turn left onto Byron Street. On the right-hand side of Byron Beside the church, at the corner of 4.